When France locked down, this doctor became a lifeline for her rural community

In Haute-Alsace, where hospitals are scarce, Dr. Dominique Spihlmann is the first responder for an isolated community of 10,000.

Orbey, France — I cross the mountain pass at night. When the coronavirus pandemic first hit Europe in March, I was at the epicenter in Lombardy, Italy, documenting the disease as it carved through the region. Then, hearing that the virus was spreading through the mountainous villages in northeastern France where I grew up, I called Dr. Dominique Spihlmann, the local doctor. She told me she was seeing up to 10 cases of COVID-19 each day. I decided to go back to Haute-Alsace to document her experience with the disease.

After four hours, the straight highway is replaced by the narrow, winding roads I know so well. I settle in quietly at my father’s small farmhouse high in the mountains, but I decide not to have physical contact with my family for fear of getting them sick. Though I am home, it doesn’t feel like home.

The next day, I visit Dr. Spihlmann, a small woman in her 40s. Her eyeglass frames are yellow, and the shape of France surrounds each eye. Like me, Dr. Spihlmann was born and raised in a small village in the Haut-Rhin district. It became a coronavirus hotspot in late February after 2,500 people from around the world attended a five-day evangelical conference at the Open Door Church in the city of Mulhouse. (See how coronavirus has spread around the world.)

Since then, more than 3,300 people have died from COVID-19 in the Grand Est region. The mortality rate has increased by 269 percent compared to 2019. The closest hospital is 25 km (16 miles) away, making Dr. Spihlmann the first responder in a rural and isolated community of 10,000 inhabitants. Each day, she juggles COVID-19 patients with her regular caseload in five villages spread across three small valleys.

Dr. Spihlmann’s day starts at 8 a.m. Walk-ins are no longer allowed at her practice; patients must call ahead before coming. Around 10 a.m., a boy arrives with his mother to receive a vaccine. “You can sit on the bed,” the doctor says. “I have disinfected it, don’t worry.” She is constantly disinfecting: the bed, the door, her pen. The phone rings and rings, consultations with patients too afraid to come in. While on the phone with a psychologist, discussing an anxious patient, Dr. Spihlmann jokingly tells her, “Soon you will have to take care of me.” After five appointments, she grabs her medical equipment and hits the road in her white Range Rover. Many of her elderly patients can’t come to her, so she goes to them.

In urban areas, coronavirus patients have flooded hospitals. In the countryside, where hospitals are few and far between, the pressure has fallen onto general practitioners like Dr. Spihlmann. During the virus’s peak in France, in the last week of March, GPs diagnosed 40,000 cases. They didn’t receive the personal protective equipment that the French government requisitioned for hospitals, and had to rely on their communities to help find PPE. Ten French GPs have died of COVID-19, most of them in Grand Est, including one Dr. Spihlmann worked with. “It really started to get to me when the doctor who substituted for us during our vacation time passed away,” she says. (Hear from a Baltimore nurse coping with the unrelenting pressure of the virus.)

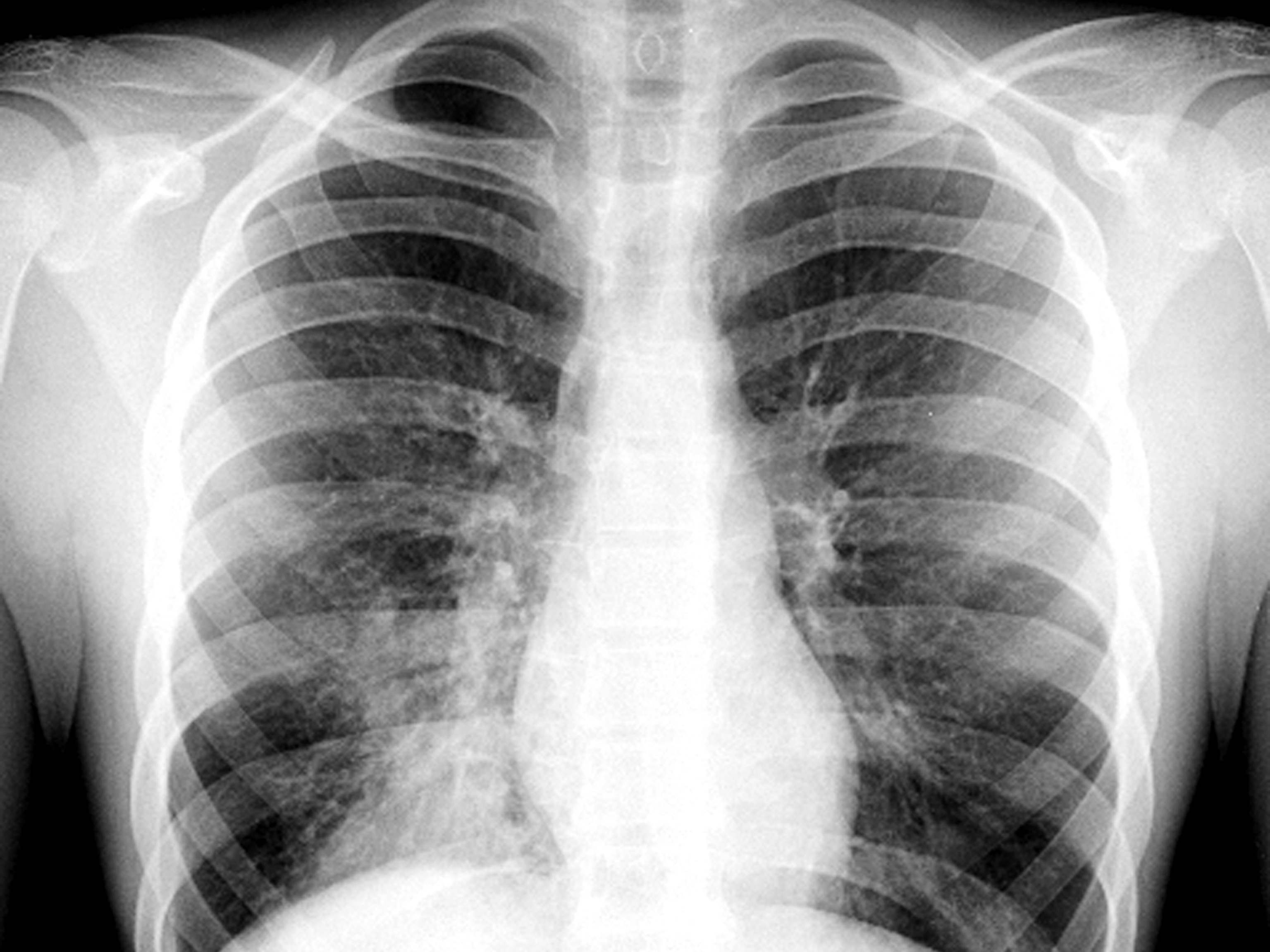

She stops at a home in the village of Labaroche, where a man greets her at the top of the stairs. His girlfriend and daughter both have COVID-19. He is very pale and not wearing protection. With global demand skyrocketing, masks are hard to come by. Dr. Spihlmann gives him one before seeing the patients. The woman had a high temperature during the night, but there’s no indication of lung damage. The daughter seems more stable than the girlfriend. Dr. Spihlmann prescribes an antibiotic to try and keep their condition from worsening.

“It pains me because I don’t know what else I can do for them really,” she says. “This situation is unprecedented in my professional career.” If they start being unable to breathe, they will have to be moved to the hospital—a last resort here in the valley as hospital beds in the nearest city are limited.

Because the family has been under quarantine, the man does not have cash to pay the doctor. A neighbor helps him out. “Good luck and call me if you need anything,” Dr. Spihlmann says. She carefully takes off her protective jumpsuit and gloves in the rainy parking lot and hops back in the car. Her next stop is on the other side of the mountain, 20 minutes away.

In the valley empty of cars or pedestrians, we drive around for hours visiting patients, washing our hands, changing our protective equipment. Dr. Spihlmann never stops talking—a useful skill for someone who, on average, has seen 17 patients a day for the past 18 years. She knows all about each of her patients, from their medical history to their love lives. Part of her job is to spot environmental issues that could cause medical problems.

Country doctors like her are a dying breed. In rural France, 47 percent of the GPs are more than 60 years old. France produces the world’s second-smallest pool of new doctors each year, and the majority of new graduates practice in the cities. Dr. Spihlmann’s business partner is retiring this year, and she has had trouble finding a young doctor to replace him. (Rural hospitals may not survive COVID-19. Can telemedicine save them?)

We arrive at the COVID-19 unit of one of the four nursing homes Dr. Spihlmann oversees. We put on protective jumpsuits, FFP2 masks, and shoe covers. Like elsewhere in the world, nursing homes in Grand Est have been severely affected by the virus. In April, after 6,528 residents and 4,343 staff in the region tested positive, the COVID-positive residents were moved into a special wing. There, Dr. Spihlmann consults with nurses and caregivers to treat the patients, coordinate logistics, and test staff for COVID-19.

“This one responds very well to music,” she says about a patient. She takes a pink teddy bear and strokes the cheek of a bedridden woman, who opens half an eye. Since the beginning of the lockdown, residents have been confined to their rooms. The medical staff are the only people they have seen, and Dr. Spihlmann is starting to notice patients developing psychological or behavioral problems such as worsening dementia, mutism, or violence. One resident bursts into tears when she sees us. Isolated in their rooms and cut off from their families, they are entirely dependent on the staff. A few are able to speak to their loved ones over videoconferences

After a long day, Dr. Spihlmann arrives home around 8:30 p.m. and undresses in an improvised decontamination area in the garage. She takes her shoes off at the entrance, throws her clothes directly into the washing machine, and showers in the basement. Despite her precautions, her husband Vincent still instinctively takes a step back from her on occasion. She sometimes forgets where she is and wears a mask inside her home. Vincent and their teenage sons, Tom and Basile, have been trying to help her deal with the pressure of her work while they are confined at home. “At one point she was so stressed she was always yelling at us,” says Basile. That night, Dr. Spihlmann and her husband play a duet on clarinet and piano to relax.

I return home to my family’s farmhouse. My brother, who is sick, is isolated in a room in the back of the house, communicating with me only through text messages though he is just 50 meters away. Dr. Spihlmann gives me a few FFP2 masks for my brother’s wife and daughter. I leave his medicine in front of his window. I try to find an oximeter, to measure the oxygen level in his blood, but they have all been requisitioned by the state for hospitals. We’re worried that my father, who is high risk because of a preexisting health condition, might get sick too. At night, the sound of my brother’s coughing makes my heart race.

My brother has since recovered. I still worry that my father will get sick. I still think about driving around the countryside with Dr. Spihlmann, from farmhouses to nursing homes, taking pulses and providing chit-chat. Sometimes we were the only people they had seen in weeks. As lockdown separated grandparents from grandchildren and sent young and old into forced solitude, she remained the bond tying the community together.

Isolation is the inescapable toll of this pandemic, suffered by those who don’t get the virus and those who do. In the valleys around my family home, the houses are so spread out many people have no neighbors. Their children, who work in the cities, can’t visit. The markets which bound the community together are closed.

I thought I could find peace in solitude. Instead, after months of covering the pandemic, I’m craving home—because even if I am there, I am not.