These women first made mushrooms a trend—back in the 1800s

From Lion’s Mane supplements to mushroom 'leather' shoes, mushrooms are having a moment right now. But the trend isn't new—these 19th-century women were among the world's first fungi fans.

Beautiful, gruesome, delicious, deadly: Mushrooms wear many different hats. Some of the most mysterious and fascinating organisms on our planet, they became more popular than ever when the pandemic forced people back out into nature in 2020. Walks outside led to love affairs with the mushrooms they found there.

But these days, it’s easy to spot a mushroom even if you’re not walking through the woods. Whether its jewelry, home décor, innovations in sustainability, a food trend, or even wellness, mushrooms have seemingly taken over our lives—and we have women to thank for that.

At the forefront of this latest fungi craze are the “mushroom ladies.” Gabrielle Cerberville or “Mushroom Auntie” has a million+ followers on TikTok and posts energetic or “chaotic” videos of her foraging finds. Alexis Nikole or “Black Forager” is another heavy hitter with 4.5 million followers on TikTok and 1.8 million followers on Instagram. Giuliana Furci, the first female mycologist in Chile to study non-lichenized fungi, is the founding director of the Fungi Foundation and a National Geographic Explorer who holds a sturdy 125K Instagram followers.

But mushroom ladies aren’t new. This is just the latest generation.

The original mushroom ladies

Going back to the 19th century, women like Mary Elizabeth Banning, Beatrix Potter, Anna Maria Hussey, and Marie-Anne Libert were living the mushroom life. Despite household and family burdens, and roadblocks placed by scientific institutions, these women were documenting and discovering fungi species all on their own.

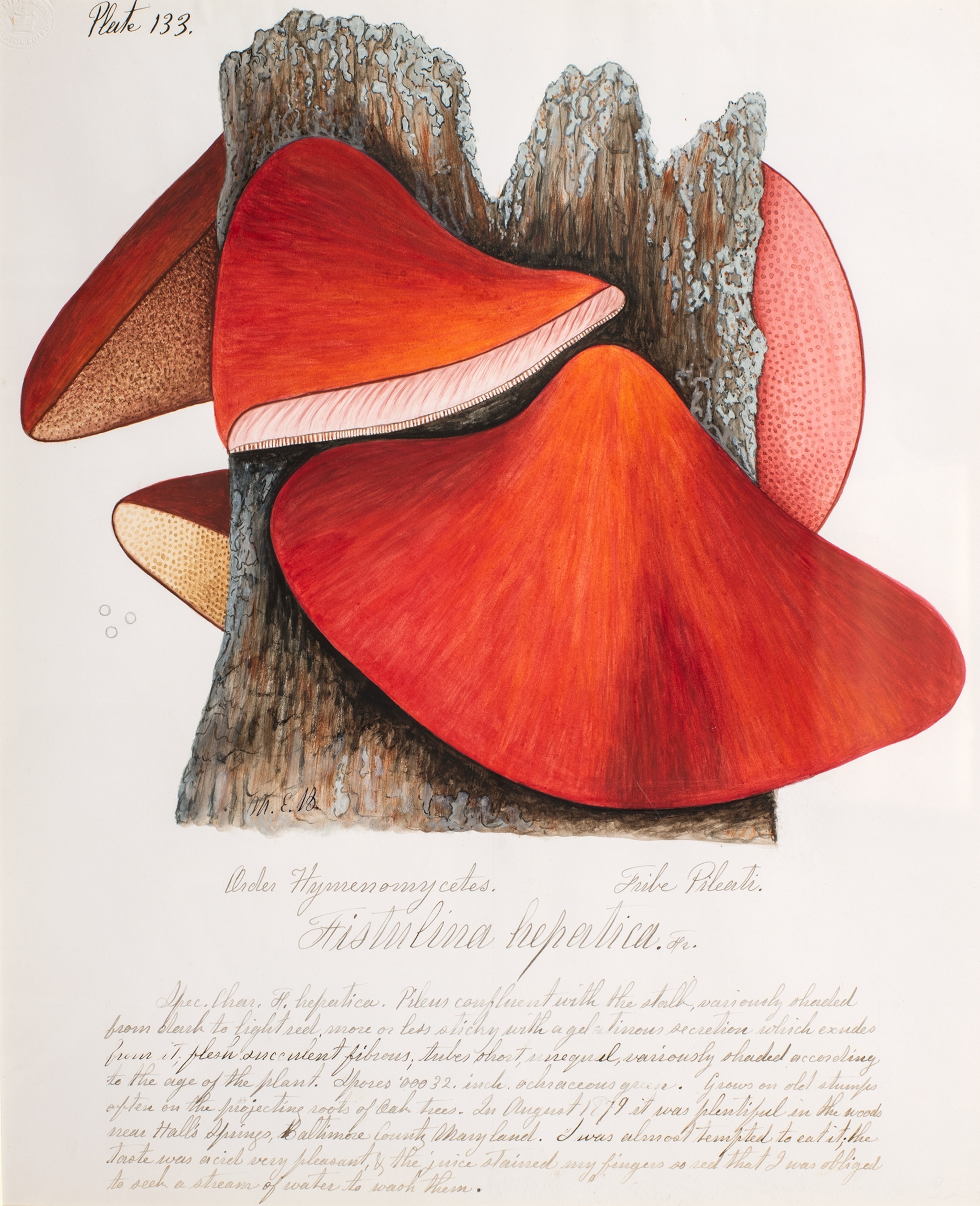

Although Mary Elizabeth Banning (1822-1903) was busy caring for her elderly mother and sick sister, she made time to hit the woods in search of fungi. Collecting mushrooms all around Maryland, she put together an impressive catalogue of her findings that included 175 water color illustrations and descriptions, and even some new-to-science species. She became the third woman in history to identify new fungi species to science. Even though Banning corresponded frequently with the renowned mycologist Charles H. Peck—to whom she entrusted her manuscript—her work remained unknown until it was discovered 100 years later. Now her book has a prominent home at the New York State Museum in Albany.

From 'Peter Rabbit' to mushroom paintings

Helen Beatrix Potter (1866–1943) is best known for her children’s stories and illustrations like The Tale of Peter Rabbit, but most people don’t know that she was a mushroom lady. Over the years, on trips to the Scottish countryside with her family, Potter completed 350 paintings of various mushrooms and lichen.

Although her interest in fungi began as an appreciation for their complexity and beauty, Potter soon leaned deeper into the science of mycology through more and more detailed paintings—even microscopic depictions of mushroom spores—that were used by other fungi enthusiasts for identifying purposes. Potter was accepted to study mycology at the Royal Botanical Gardens in Kew, London, and submitted a research paper to the Linnean Society of London. Unfortunately, she was forbidden from attending the standard proceeding and presentation for papers because she was a woman.

While Anna Maria Hussy’s (1805-1853) husband was looking up to the heavens with his interest in astronomy and career as a rector, his wife was looking down at the forest floor as an independent thinker and budding mycologist. With three kids at home, Hussey rolled her eyes at the expectations of mothers and wives. Proving that women were capable of more than simply being a housewife, she held her own as a breadwinner with the sales of her mycological illustrations. Although Hussey was one of the first women allowed to attend scientific meetings, she often had to publish under her husband’s name. Hussey ultimately published under her name for her book Illustrations of British Mycology, where along with tips on how to identify mushrooms she suggested how to prepare edible fungi.

If you’ve heard of potato blight, famous for Ireland’s Great Famine from 1845 to 1849, you might know Marie-Anne Libert (1782-1865) who was one of the first people to identify the fungus-like microorganism responsible for the plant disease. Born into a large family, Libert’s academic potential stood out to her father from an early age. Although women of her time weren’t admitted to university, her father made sure she received an education. Thanks to his forward thinking, and Libert’s perseverance in studying Latin and reading scientific literature on plants, she became the second woman to name a fungal taxon, and discovered over 200 novel taxa during her lifetime.

It can only be assumed that if they were alive today, Potter would be swallowing Lion’s Mane supplements, Banning sporting sustainable mushroom leather shoes, Hussey reading besides the glow of a mushroom lamp, and Libert posting her latest fungal find on Instagram.

Even while facing numerous obstacles, these women served as important sources of intellect and influence in not only the advancement of mycology, but today’s continued embrace of all things fungi. And the work of the mushroom ladies is still not done. Scientists estimate that there are between 2.2 to 3.8 million species in the world, but less than 10 percent of them have been cataloged. Taking a page from the past, today’s mushroom ladies (and gentlemen) have plenty of discovering left to do.