How supercomputers paved the way for laptops and chatbots

Enormous dimensions, complicated military calculations, and thousands of vacuum tubes—this was the early supercomputer.

In the 1940s and ‘50s, programmable machines capable of performing calculations and operations on a scale never seen before were developed, mainly in the United States. Although of enormous dimensions, they were the prototypes for the personal computer.

(See how new technology transformed the American workforce.)

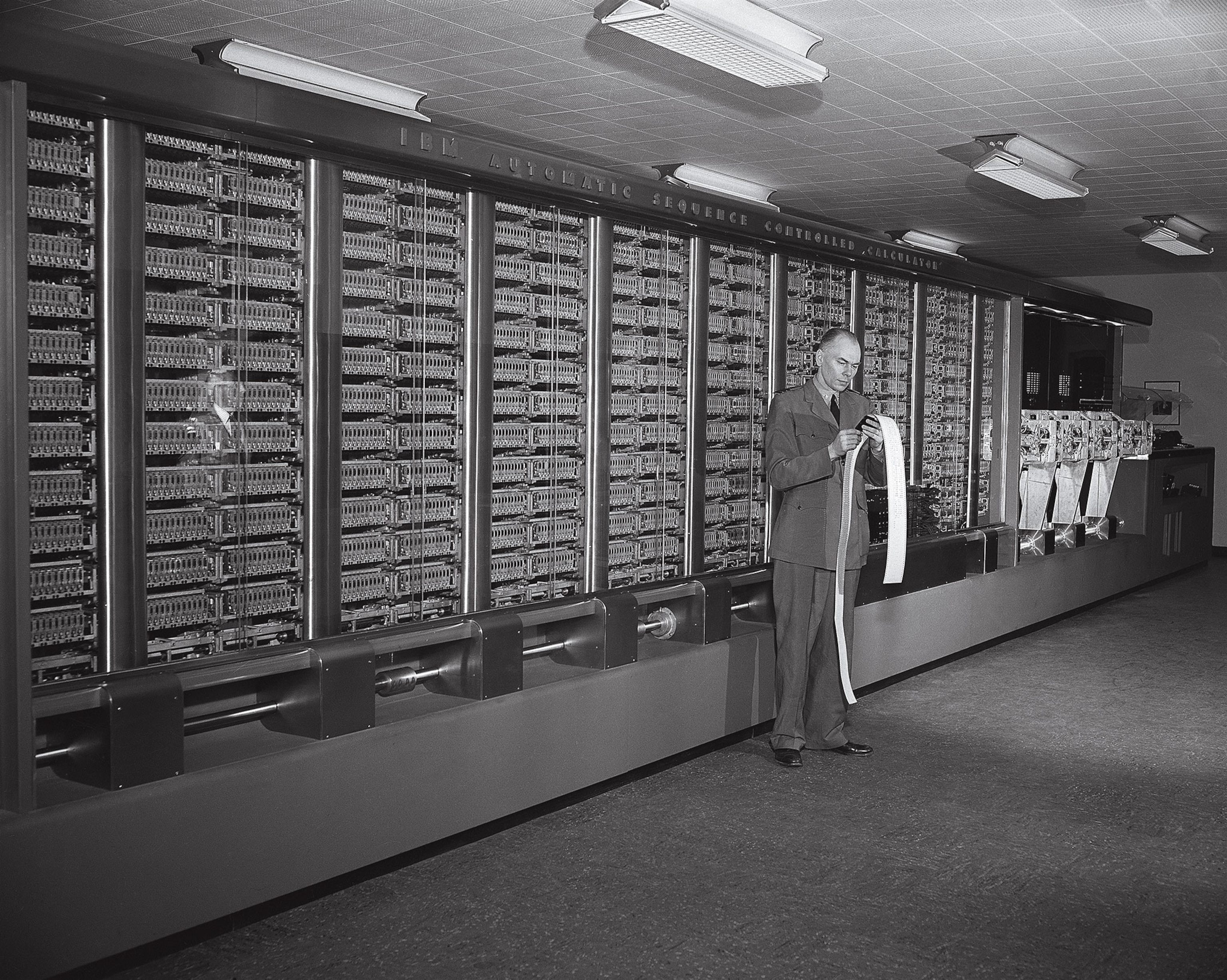

Mark I (1944)

In 1936 Howard Aiken, a graduate student at Harvard University, decided to create a programmable computer inspired by the 19th-century work of English mathematician Charles Babbage. In 1939 Aiken secured funding from IBM. Two years later the United States Navy joined the initiative, with the aim of using the machine to determine the trajectory of long-distance projectiles, a calculation of high complexity. The Mark I was completed by a team of men and women in 1944 and was used, among other things, to calculate the range of the atomic bomb’s implosion. The Mark I was of imposing dimensions: The device was nearly 50 feet long, weighed five tons, and had 750,000 components. The three punched tape readers at the back of the room were used for the introduction and collection of data, among other elements. Aiken, in his Navy uniform, examines one of the tapes.

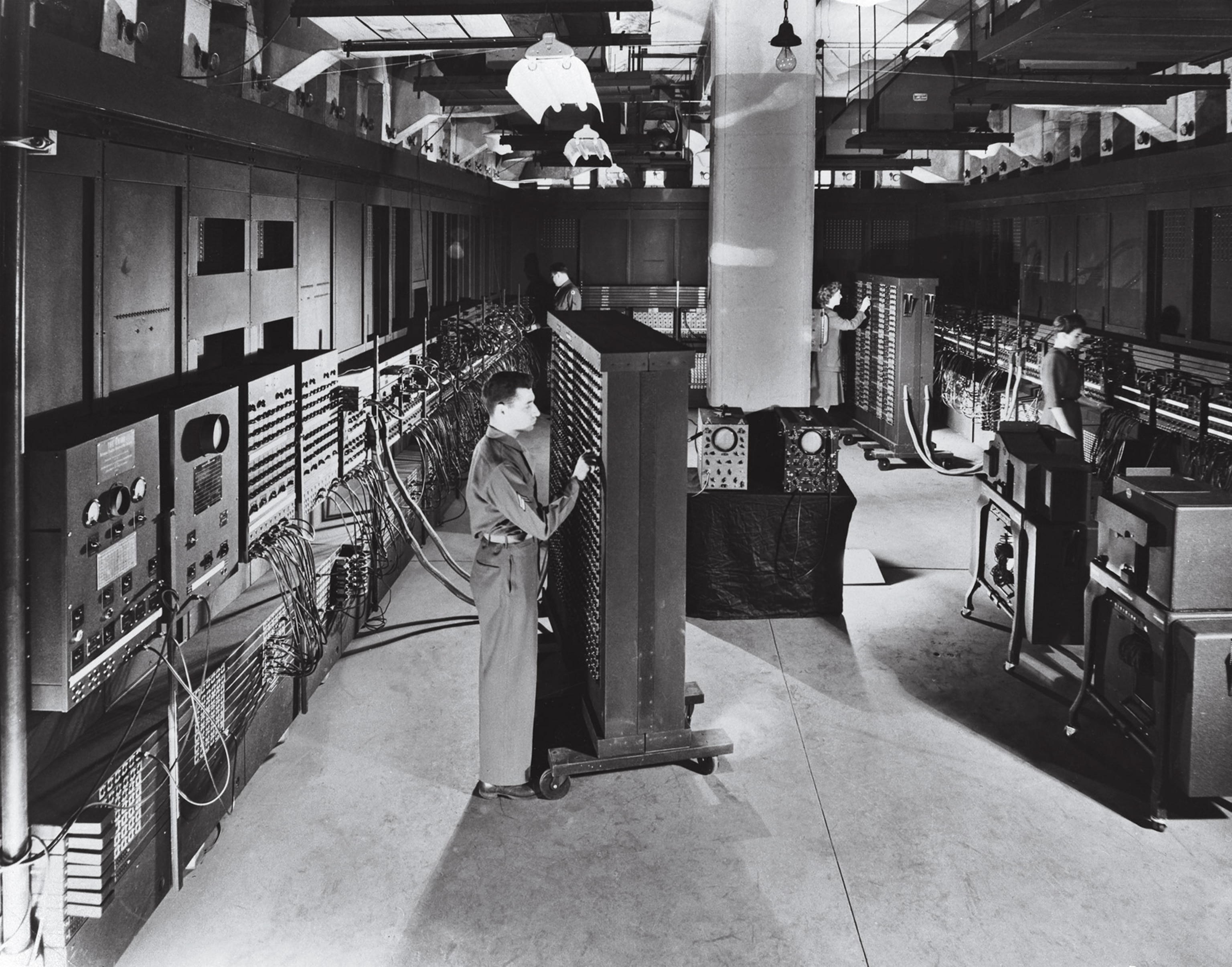

ENIAC (1945)

In 1943 the United States Army funded a computer project led by two University of Pennsylvania engineers, John Mauchly and John Presper Eckert, Jr. The goal was to create an electronic machine that would be faster and more reliable than the mechanically based Mark I. The ENIAC (Electronic Numerical Integrator and Computer) occupied an entire room measuring 50 by 30 feet, with 40 panels more than six feet high. The ENIAC contained over 17,000 vacuum tubes, which regulated the electrical circuit much more quickly and efficiently than the Mark I’s mechanical switches. The computer was programmed using three function boards. It could make 5,000 additions per second, while the Mark I could make fewer than four. Introduced to the public in February 1946 as “the world’s first electronic computer,” the ENIAC was used by the military to calculate the feasibility of a proposed design for a hydrogen bomb.

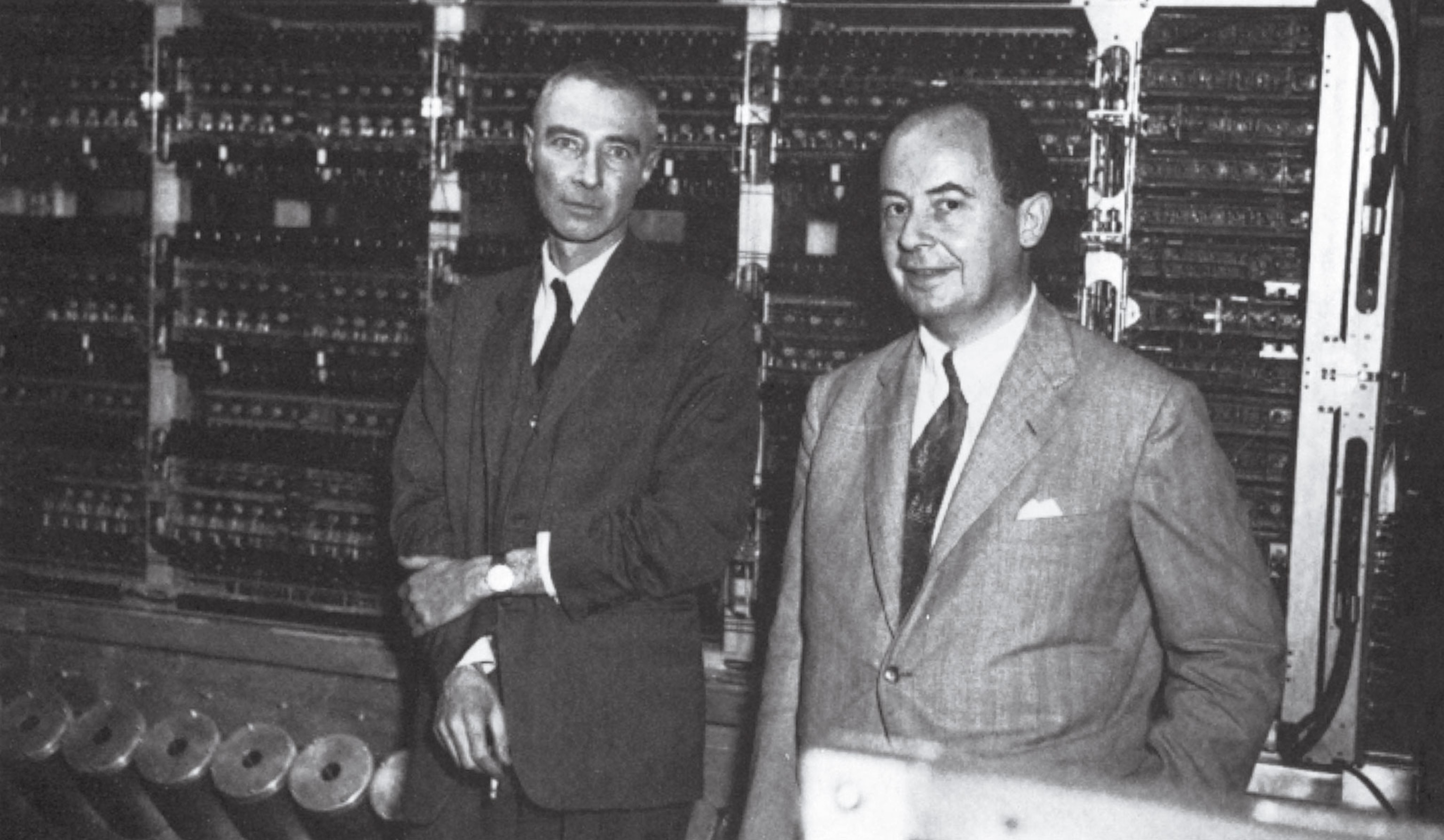

EDVAC (1949)

At the end of World War II, there was widespread interest in creating the “universal computer” envisioned by the British scientist Alan Turing. American theorist John von Neumann published a pioneering article in 1946. In it he pointed out that the computer of the future would work with programs stored in the same memory as the data, instead of using an external electronic board for this function.

(Oppenheimer: The secrets he protected and the suspicions that followed him.)

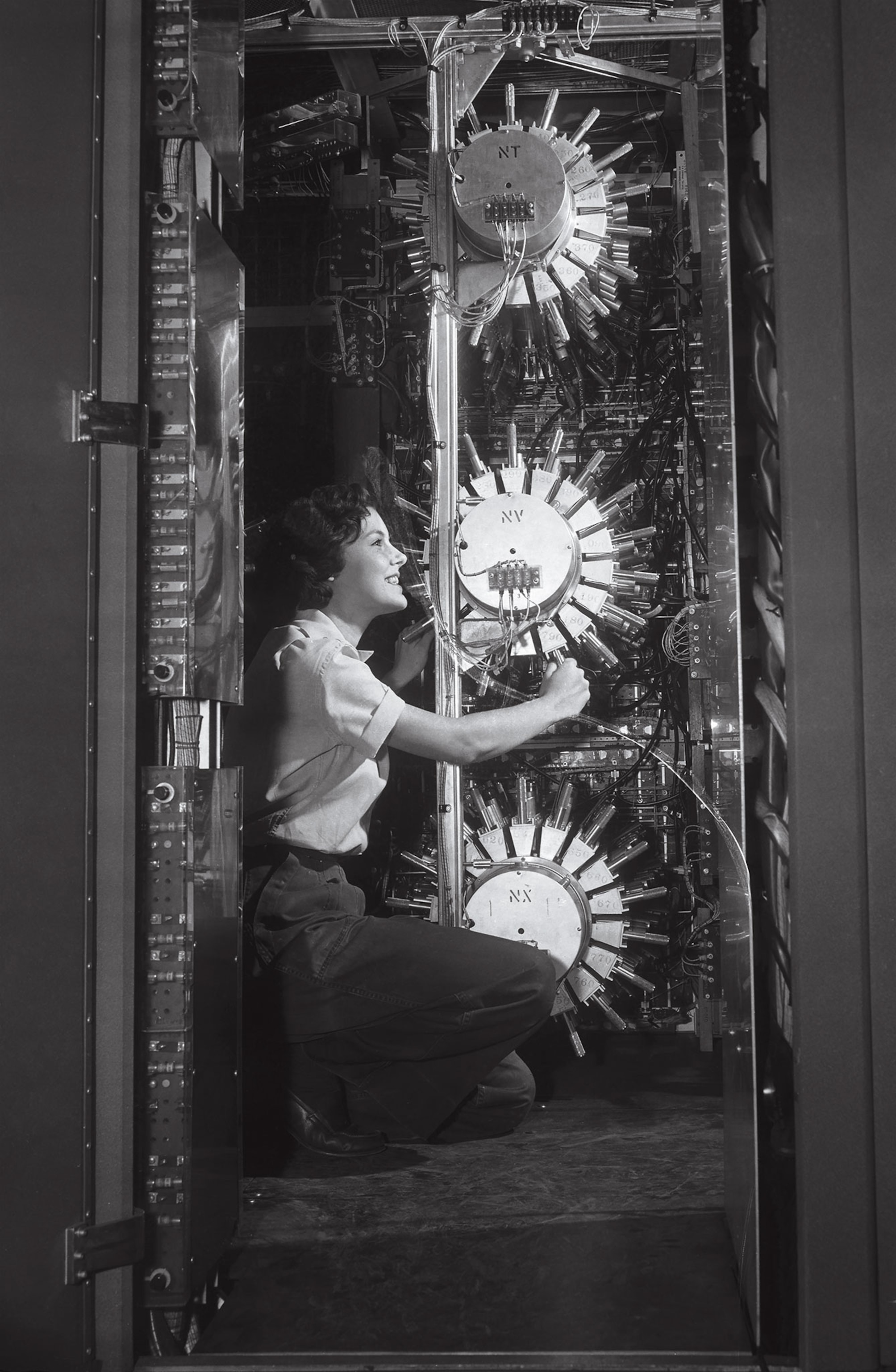

That same year, the inventors of the ENIAC, Mauchly and Eckert, began the construction of the EDVAC (Electronic Discrete Variable Automatic Computer). Presented in 1949, it was the second computer of the von Neumann type with memory holding both data and instruction, after the EDSAC (Electronic Delay Storage Automatic Calculator) was built at the University of Cambridge three months earlier. The EDVAC introduced a new information-storage system: the mercury delay line, a predecessor of the transistor. This made it possible to reduce the use of vacuum tubes, which frequently melted. The EDVAC occupied 490 square feet of surface area.

UNIVAC (1951)

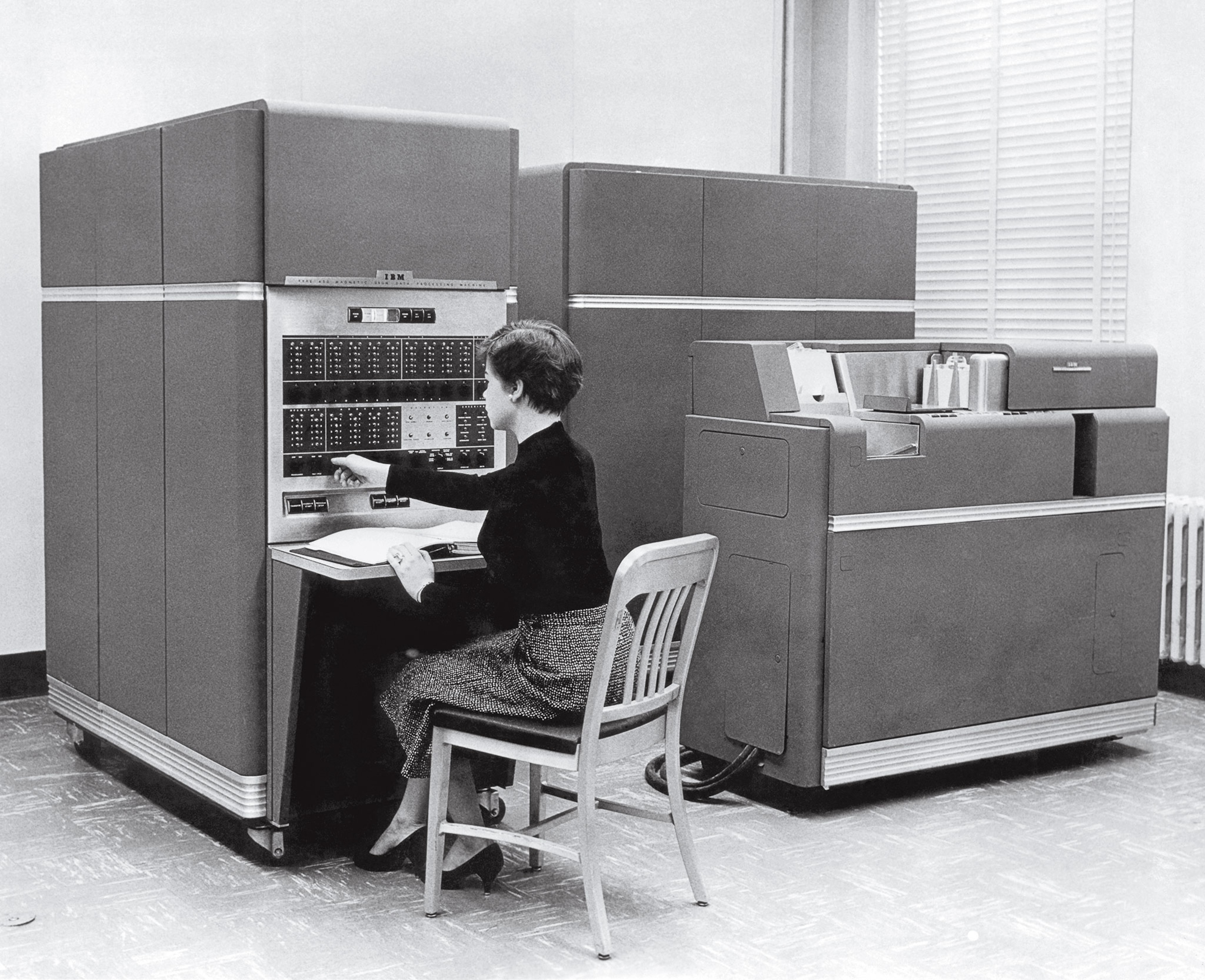

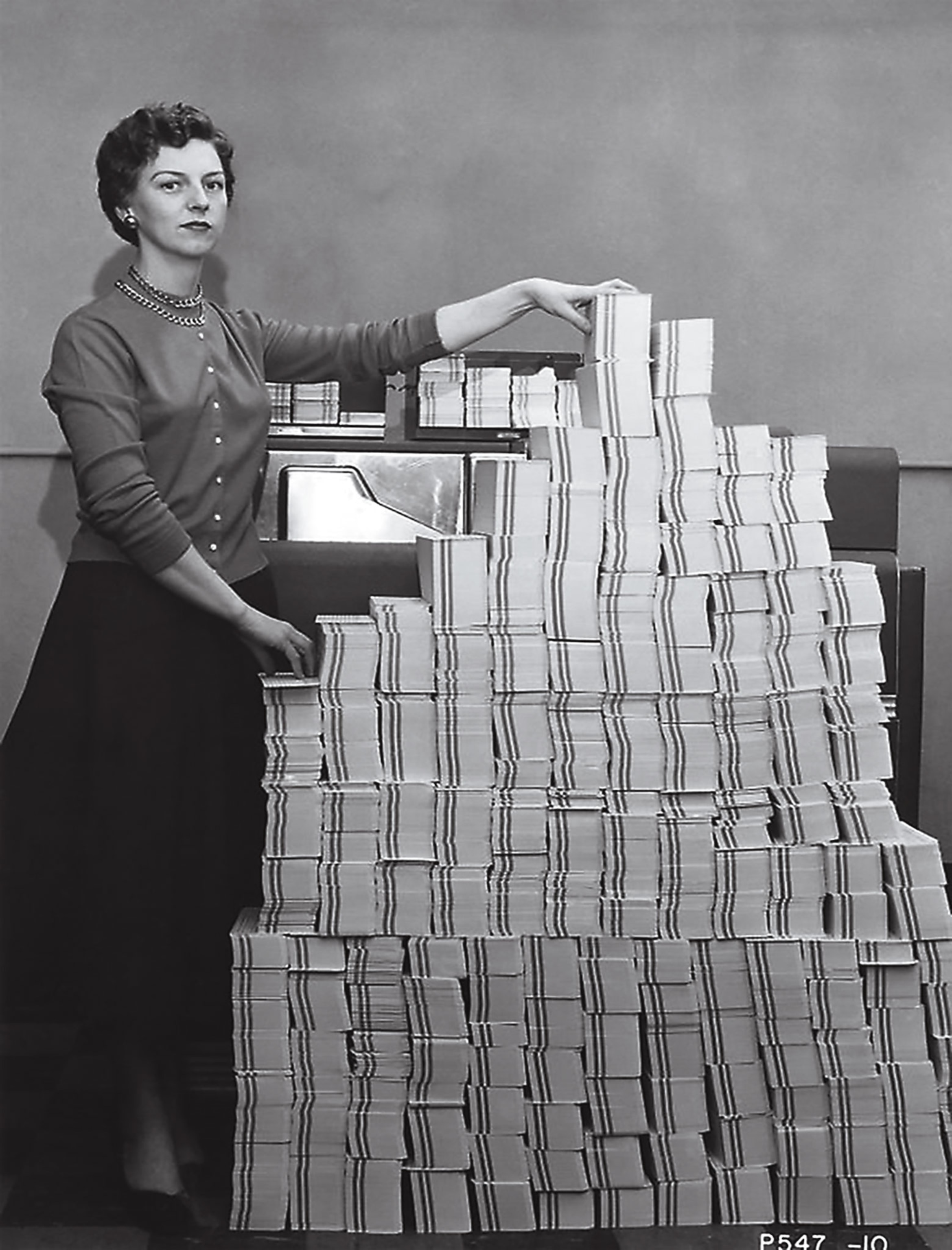

The EDVAC was used to calculate ballistic trajectories for the military, but its designers were also interested in creating computers for civilian use. In 1946 Eckert and Mauchly won a contract to build a computer for the U.S. Census Bureau, which would replace the tabulating machines used since the late 19th century to summarize information stored on punch cards. Although the duo ran into financial difficulties and their company was acquired by the typewriter manufacturer Remington, in 1951 they introduced the UNIVAC (Universal Automatic Computer). In its electronic circuits, the UNIVAC also used mercury delay lines for memory, which allowed the number of vacuum tubes to be reduced to 5,000.

As a result of their reduction, the computer was smaller, but no less powerful. It could read 7,200 decimal digits per second. The photo below shows how the information was entered using a keyboard and a console. The results were recorded on magnetic tape, rather than punch cards, an innovation that census officials took time to get used to. The information on the magnetic tape was then printed out onto a continuous ream of computer paper.

IBM 650 (1954)

The development of computers directly threatened the business of IBM, a company that had prospered since the early 20th century by manufacturing punch card machines. IBM’s response was to develop its own computer. In 1954 IBM engineers presented what would be the first successful commercial computer. The IBM 650 cost $500,000, compared to a million dollars for the UNIVAC. In eight years, 1,800 units were sold. However, the IBM 650 was a far cry from modern computers: It worked with a magnetic drum memory instead of a hard disk (which IBM introduced in 1956); it used vacuum tubes instead of transistors (IBM’s competitor Bell Labs fully transistorized a computer in 1954, and IBM followed in 1959); and the programs were recorded on punch cards inserted by means of classic tabulating machines.

Computer scientist Donald Knuth credits IBM for developing university computing classes: “IBM donated about 100 ‘free’ computers during the 1950s, with the stipulation that programming courses must be taught.”