How suspicion and intrigue eroded Alexander's empire

Plots of murder, both real and imagined, consumed Alexander the Great's thoughts, turning him against former comrades in arms.

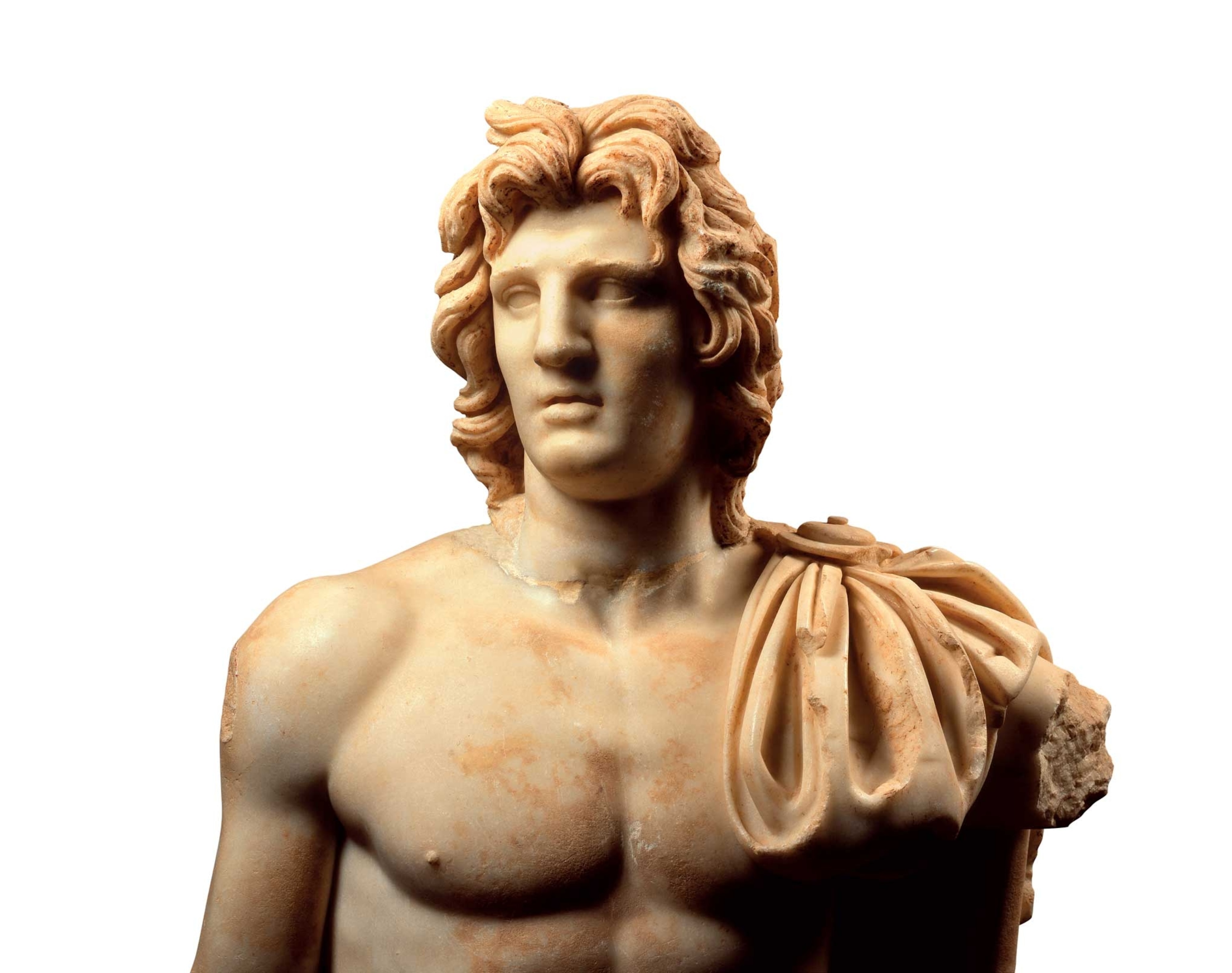

Alexander the Great’s accomplishments in the fourth century B.C. were breathtaking. The son of a powerful king and an ambitious queen, Alexander was born in 356 B.C. He studied under Aristotle until age 16 and became king of Macedon at age 20. In his 13-year rule, Alexander united ancient Greece, conquered Persia, seized Egypt, and created an empire stretching from Europe to Asia. He fancied himself the descendant of Achilles and the son of Zeus.

As Alexander’s power grew, so did his fear of losing it. At times megalomaniacal and paranoid, he began to see threats everywhere, including among those closest to him. He believed they envied him. He believed they wanted his power. He believed they wanted him dead.

Bold Beginnings

Alexander’s brilliant start won him many loyal followers, comrades in arms who helped him on his quick rise to glory. In 334 B.C. Alexander’s forces advanced unfaltering across Anatolia (modern-day Turkey) and invaded the Achaemenian (Persian) Empire. They scored two victories: the first near the Granicus River near the site of Troy, and the second in Issus.

Having rejected an offer of a truce from an increasingly rattled Darius III, leader of Persia, Alexander entered Persia-controlled Egypt in 332 B.C.

He was received there as a liberator from the Persian overlords, and founded Alexandria, the most famous of the cities that he would name for himself. Journeying far into the desert near the modern-day border with Libya, Alexander had a brush with divinity that only stoked his sense of omnipotence. The young king and his men slogged through the desert to the Siwa Oasis, home of the oracle of Amun—associated by the Greeks with Zeus—whose starstruck priests proclaimed him the god’s son.

Generation Gap

Having routed Darius at Gaugamela, Alexander enjoyed a warm welcome in Babylon, hosted by Mazaeus, the Persian satrap (regional governor). Although Alexander considered Babylon to be the seat of his new government in Asia, he allowed Mazaeus to continue in his position as satrap, with some powers curtailed. This decision was key to Alexander cementing power, but some of his Macedon followers were resentful of Mazaeus, who had fought against them at the Battle of Gaugamela. The incident marked a continuing trend: Alexander built up a parallel court of satraps and eunuchs, introduced Asian rituals into court, and later married a Bactrian princess, Roxana. His entourage of Macedons, older men who had fought for Alexander’s father, Philip II, began to resent this behavior on both generational and cultural grounds.

Brimming with confidence, Alexander went on to defeat Darius for the third and final time at Gaugamela (near Arbil in modern Iraq) in 331 B.C.

Following this victory, accompanied by his generals, Alexander took Persia from Darius III and added more land to his expanding empire. Still hungry for more, Alexander continued his campaign east. Cities fell to him, one after the other. He took control of Babylon, Susa, and other capitals of the Achaemenian Empire, and with them their vast wealth.

Soon after the victory at Gaugamela, Darius III was assassinated in 330 by one of his own provincial governors, or satraps. As Alexander began consolidating power, he adopted Persian customs, a move which many of his Greek compatriots found insulting. Alexander’s magnificent victories had not been won single-handedly. These close friends and companions—Ptolemy, Craterus, Cleitus the Black, loyal Hephaestion, and the grizzled general Parmenio—had been at his side throughout the Asiatic campaign.

Parmenio and Philotas

A Macedon of long-standing noble lineage, Parmenio had been a right-hand man to Alexander’s father and then served as second-in-command to Alexander. He enjoyed close bonds with both the court and the army. Already in his 70s, Parmenio had several sons who served under Alexander. The oldest, Philotas, was perhaps the most outstanding. Alexander had chosen him to command the hetairoi, or Companion cavalry, an elite corps formed entirely from members of the Macedon nobility.

Philotas had a reputation for bravery and hard work as well as being a generous and loyal friend. Some thought him arrogant and were suspicious, and perhaps envious, of his accomplishments. Philotas didn’t always agree with Alexander and had been a vocal critic at times, especially of the way the king had been hailed as a god in Egypt.

Father and Son

Some of Alexander’s generals, led by Craterus, heard whispers that Philotas could be plotting against Alexander. They ordered spies to keep tabs on him, but the only account of treasonous talk they found came from a Greek prostitute. She told them that Philotas bragged to her about how he and Parmenio were responsible for Alexander’s victories. Craterus reported his findings to Alexander, who did not give much credence to pillow talk. He trusted Philotas and also did not want conflict with Parmenio, whom he had long trusted.

In 330 B.C. whispers revealed another treasonous plot of Philotas, except this time assassination was involved. While wintering with his army at Phrada (modern-day Farah in Afghanistan), Alexander learned that a man named Dymnus, a member of the hetairoi, planned to murder him. An informant, the brother of Dymnus’s lover, had twice told Philotas of the plot, but Philotas had done nothing. Finally, the informant went directly to Alexander to expose Dymnus.

Before he could be arrested, Dymnus killed himself, leaving many mysteries unresolved. Alexander, convinced of his guilt, had Dymnus’s corpse publicly displayed to warn potential traitors. Having grown suspicious of his friend, Alexander then called on Philotas to answer why he had not reported the plot to his leader.

Philotas denied being part of a plot to kill Alexander, arguing that the allegations had seemed trivial, the result of a lover’s quarrel. Writing his Histories of Alexander the Great around the first century A.D., Roman author Quintus Curtius Rufus reported how Philotas threw his arms around Alexander and begged him “to have regard to his past life rather than to a fault, which, after all was only one of silence.” Philotas agreed to let the army determine his fate.

Alexander called an assembly of the Macedon army to judge him. In front of them all, Craterus accused Philotas not only of having kept the murder plot secret but of actually having instigated it. After hearing all the arguments, the army considered the evidence: They found Philotas guilty of treason and sentenced him to death for his treachery.

Brothers in Arms

Hephaestion had been Alexander’s close friend from childhood, probably taught by Aristotle alongside the young prince. The two were close in age, with sources putting Hephaestion’s birth in 357 or 356 B.C., and some historians believe the two were lovers as young men. One popular account puts the comrades near the river Granicus in Anatolia (modern Turkey) on the way to battle the Persian army in 334. Alexander visited the tomb of Achilles, his alleged ancestor, while Hephaestion paid his respects to Patroclus, Achilles’ dear companion. The two were said to look so alike that they were often mistaken for one another. Hephaestion stayed in Alexander’s favor throughout his career. His sudden death in 324 B.C. deeply affected Alexander, who openly mourned his lifelong friend.

Alexander’s inner circle was too beset by ambition and jealousy to let the matter end with Philotas’s death. Hephaestion took the floor and proposed that they torture the condemned before executing him, in order to find out who else was involved. Hephaestion, Craterus, and others tortured Philotas all night, until his will was broken. They forced him, again under torture, to give details of the alleged plot and all those involved. The following day the former commander of the Companion cavalry was stoned to death.

Out With the Old

Paranoia, intrigue, and ambition had won the day. From that moment, there were no more trials. The ranks of the army were simply purged, leaving no one with any doubt that perceived disloyalty would be punished. Alexander knew that promotions could shore up his power. If Hephaestion had sought Philotas’s downfall to secure his own advancement, he was successful: The king made him joint commander with Cleitus the Black of the Companion cavalry, the position previously held by Philotas. Cleitus had saved Alexander’s life during the battle at Granicus and was well connected with the men who served under Alexander’s father. But, like Philotas, Cleitus had criticized Alexander’s autocratic aspirations, and Alexander wanted him where he could be easily controlled.

A Skilled Negotiator

Bagoas, a young eunuch, first met Alexander following the death of Darius III. He had been sent on behalf of Nabarzanes, a Persian military officer who had helped slay Darius, and whom Alexander—as Darius’s successor—could consider punishing as a murderer of his king. Writing in the first century a.d., Quintus Curtius Rufus recounts that Bagoas, “of uniquely lovely looks,” argued successfully that Nabarzanes be pardoned and later became Alexander’s lover. The implication that Alexander’s judgment was swayed by Bagoas’s looks was later echoed by Plutarch, who wrote of Alexander’s enthusiastic response to Bagoas’s dancing. Another source, Arrian of Nicomedia, however, generally portrays Alexander as able to resist his attraction to Bagoas. Some historians argue that Bagoas’s plea to Alexander was strengthened by his knowledge of the case, and the fact he spoke Greek. In other words, looks aside, Bagoas was probably the best negotiator for the job.

Following Philotas’s execution, Alexander embarked on what some scholars believe is his darkest deed. Alexander, perhaps paranoid, believed that there was no way Philotas could have plotted against him without the knowledge of his father, Parmenio. He also knew that Parmenio could act against him to avenge the death of his son. Alexander had to move fast to rid himself of the old man, whose loyalty had been questioned in Philotas’s trial. Despite a long life of trusted service to Alexander and his father before him, the old general Parmenio was now seen as a threat.

Although Parmenio had always been an influential figure, tensions had been growing. His age had made him cautious, in contrast with Alexander’s impetuousness. Their differences had led to frequent disagreements over the years on tactics and strategy. Parmenio had been put in charge of much of the empire’s wealth and strategic supply lines, a powerful position. Some historians have even suggested that the plot against Philotas was cooked up as an excuse to remove his father from power.

Parmenio was based in Ecbatana, a former summer residence of the Persian kings. Sources report that before his murder he knew nothing of the terrible fate that had befallen his son. While there was at least some semblance of a trial before Philotas’s execution, there would be no trial for his father. Parmenio was murdered by a courier sent by Alexander. Sources report that the courier handed a series of letters to Parmenio and then quickly killed him, an act carried out for political expediency alone. Alexander, determined to reassert his personal authority once and for all, also dispatched a small contingent to Ecbatana with orders to put down any rebellion that might ensue among Parmenio’s troops after his death.

Before setting out from Phrada to launch a new campaign, Alexander renamed the city Alexandria Prophthasia (Anticipation). He memorialized the city because it was there that he had anticipated Philotas’s alleged plot.

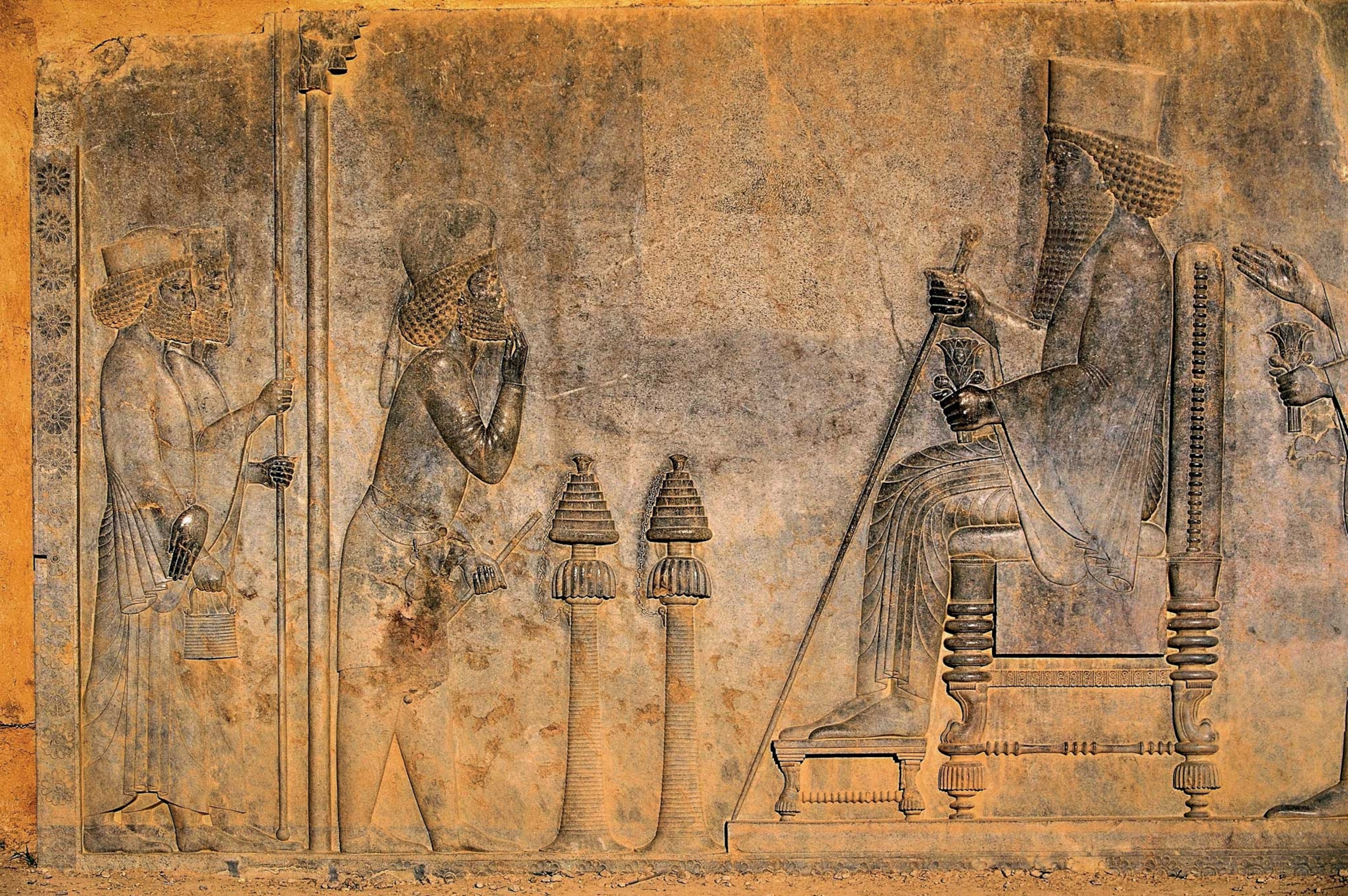

Standing on Ceremony

Among the behaviors that irked members of Alexander’s entourage was his adoption of the courtly ceremonies of his Persian predecessors. These involved complex rituals of greeting the king, which in the case of the lowliest subjects, required full prostration. Termed proskynesis in Greek (literally “kissing toward”), the practice was regarded by many Macedons as hostile to the Hellenist spirit. Worshipping a living person as if they were divine struck them as both impious and degrading. The second-century A.D. historian Arrian of Nicomedia writes of a face-off at a banquet when some figures in Alexander’s inner circle spoke of their approval of the ritual. Callisthenes, the court scholar, was having none of it. “It is unreasonable to obliterate all these distinctions by inflating human beings to excessive proportions through extravagant honors, while inappropriately diminishing gods. If one must think in foreign ways on the grounds that this argument has originated in a foreign land, then do not forget Greece, Alexander. It was for her sake that you launched your whole expedition, to add Asia to Greece.”

Remorse and Retreat

The deaths of two of his most trusted advisers did not soothe Alexander, whose character continued to degrade in the coming years. He continued to adopt what the Macedons saw as Persian manners, forgoing a warrior’s restraint in favor of decadence. For example, a Greek banquet represented the apogee of civilized society—a time for celebration, and discussion of philosophy and reason. Alexander’s banquets, however, had become characterized by debauchery, colored by passion and carnality.

The most notorious banquet took place in Maracanda (Samarqand) in 328 B.C. Alexander, then about age 28 and determined to reach India, was leading his reluctant army into harsh terrain in the east. That night, the great commander was drunk. A furious dispute arose between him and Cleitus the Black over Alexander’s increasingly Persian style and policies. Incensed by Cleitus’s accusations, Alexander murdered him in a rage with a javelin. Afterward, he was said to have felt great remorse: First-century A.D. Roman biographer Plutarch described in his Parallel Lives how “he spent the night and the following day in bitter lamentations, and at last lay speechless, worn out with his cries.”

Alexander’s actions did little to quell opposition among his followers, and other plots arose. In 327 B.C. several of Alexander’s pages were suspected of planning to murder him. One of Alexander’s associates, the biographer and historian Callisthenes, became entangled in the plot.

Plutarch said that Callisthenes “showed great ability as a speaker, but lacked common sense.” Callisthenes had loudly glorified Alexander’s exploits, disseminating the account of his incarnation as the son of Zeus in Egypt. His writing earned him favor, but it was no match for Alexander’s ego. Alexander had adopted the Persian custom of proskynesis—prostration before the king—but Callisthenes, as a Greek, would not practice it. Alexander allowed this, but historians believe that the defiance was noted.

News of the plot surfaced, and one account seemed to seal the fate of Callisthenes. Plutarch described how one of the pages asked Callisthenes how to become “a most illustrious man.” His damning answer: “By killing the most illustrious.” None of the pages named Callisthenes as a conspirator, but the damage was done. The pages were executed. For his “crimes,” Callisthenes was imprisoned and is believed to have died in prison.

In 326 B.C., having reached the edge of India at the Hyphasis (Beas) River, Alexander’s men had had enough. They mutinied, he was forced to retreat west, and his reign would never recover. Three years later, Alexander died of fever in Babylon at age 32. On that day a Babylonian astronomer dispassionately noted in his journal: “The king died; clouds made it impossible to observe the skies.” His empire would be carved up between his generals, never to rise again.