From cats to cows to crocodiles, ancient Egyptians worshipped many animal gods

As 3,000 years of art and sculpture reveal, the divine menagerie of ancient Egypt reflects the rich and varied creatures of the Nile Valley.

Sobek, crocodile-headed god of the Nile; Sekhmet, leonine goddess of war; Anubis, jackal god of the underworld; and Hathor, mother goddess with a cow’s horns: The ancient Egyptian pantheon of gods was filled with divine animals. Egyptian animal cults had extremely deep roots, going back through Egypt’s remarkably long history. Living in the lands of the fertile Nile Valley, ancient Egyptians acquired in-depth knowledge of the animals that lived there. They later transferred these animals and their characteristics to the divine realm, so by the dawn of dynastic Egypt in 3100 B.C., the gods were taking animal forms.

Ancient Egyptian belief generated such exuberant creations as the scorpion goddess Selket; the part-hippo, part-crocodile, part-lion devourer of souls Ammit; the baboon-headed (or sometimes ibis-headed) god of learning, Thoth; and Bes, a deity of the household and everyday pleasures, often depicted as comically ugly, with wings, and attributes of a lion or other beasts.

The Egyptian pantheon can appear bewildering, but it’s important to keep in mind that Egyptian cosmology lasted for millennia. As the kingdoms of Egypt changed over time, so too would its deities shift, evolve, and sometimes blend. The falcon-headed Horus’s very early role as a solar deity would be merged into Re, who was also often depicted as a falcon. Re then merges with other gods, including Horus himself, to create a Re-Horus composite god, Re-Harakhty, who is also falcon-headed.

Transformations

By the time the Great Pyramid of Khufu at Giza was built in the mid-third millennium B.C., gods and goddesses were taking on an array of animal forms. One of the most ancient was Horus the Elder. Horus was represented as a man’s body with a falcon’s head. Although he became associated with the sky, in very early iconography he is also shown in a solar bark. This vessel, sailing across the sky and down into the underworld to rise again at dawn, was a central tenet of Egyptian theology; it affirmed cosmic order, sustained by the gods, and their representative on earth, the pharaoh. Horus is known to have emerged from numerous ancient avian and falcon gods: The name Horus means “the distant one,” with the sense of the one who flies high, and so establishing the link between birds, flight, and religious awe. (Egypt's pharaohs could deliver divine justice from beyond the grave.)

Power shifts often led to a geographical shift, such as in the New Kingdom period (1539- 1075 B.C.), when pharaonic power moved from Memphis to Thebes. This shift had a theological impact, elevating the deity Amun to the position of state god, worshipped in Theban temples, such as Karnak. Often represented in his merged form with Re, Amun-Re is shown as a ram.

Amun’s ram associations go very far back to the ancient Egyptian god Khnum, creator of human beings. Amun is often referred to as the “god of two horns.” Rams were linked with fertility and war, making him a powerful protector figure for the New Kingdom pharaohs. (The pharaoh Hatshepsut claimed Amun was her father.)

Sacred cows

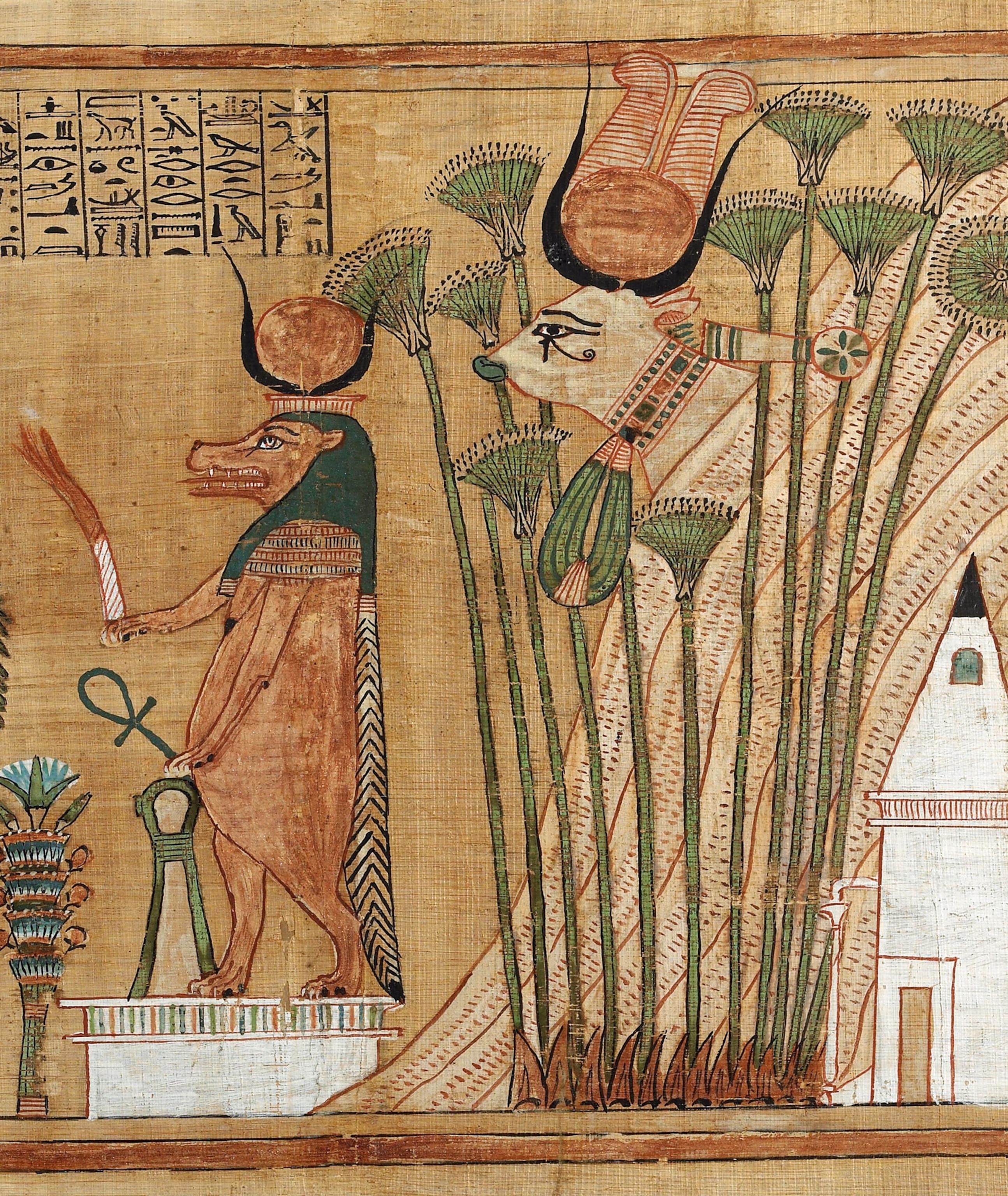

Early goddesses were often responsible for things associated with life and reproduction, including birth, fertility, and nourishment. Some of the earliest goddesses were shown with a cow’s head or horns. Bat, for example, is depicted with the horns of a cow on the Narmer Palette, an important artifact from circa 3100 B.C. that commemorated the unification of Egypt as a country. Over time, Bat seems to have evolved into another very powerful early Egyptian goddess, Hathor, who exerted influence in numerous areas of life, including motherhood, music, agriculture, pleasure, and even death.

Although she was known as “the golden one,” and would blaze brightly throughout centuries, Hathor’s role would be subsumed by the rise in importance of Isis. Usually depicted as a human female without overt animalistic traits, Isis demonstrated her animal ties in a more subtle way: She was often depicted with cow’s horns atop her head, a visual nod to Hathor. Isis would, in time, take over Hathor’s responsibilities, especially as a universal symbol of the Egyptian mother and wife in her role as consort and protector of the lord of the underworld, Osiris. (Discover: Isis was worshipped throughout the Roman world.)

Dogs and cats

Among the world’s most popular pets, dogs and cats also played prominent roles in Egyptian mythology, appearing in the Egyptian pantheon. An important deity who served the god Osiris in the underworld was the jackal-headed god of mummification, Anubis, whose role overlapped with—and later eclipsed—the jackal god Wepwawet. Historians believe that powerful canine dogs, acting in the interests of the dead, were the best protection against the jackals of the natural world, whose habit of digging up the recently buried struck fear into the hearts of Egyptians.

Feline goddesses are a popular attraction at many museums today. Some of their cults were first associated with specific cities, but as their fame spread, they became associated with similar local deities. In Memphis, for example, an important feline goddess was Sekhmet, a goddess of war. She was depicted with the head of a lioness because of her association with the desert and ferocity.

Sekhmet was a favorite of the pharaoh Amenhotep III, who commissioned hundreds of stone statues of the goddess—as many as 730—for his massive mortuary temple, built in the 14th century B.C. at Thebes. Egyptologists have theorized that the pharaoh had so many artworks commissioned both to pacify the goddess’s fearsome qualities and to attract her protective nature. (Here's how archaeologists discovered Egypt’s ancient city of divine cats.)

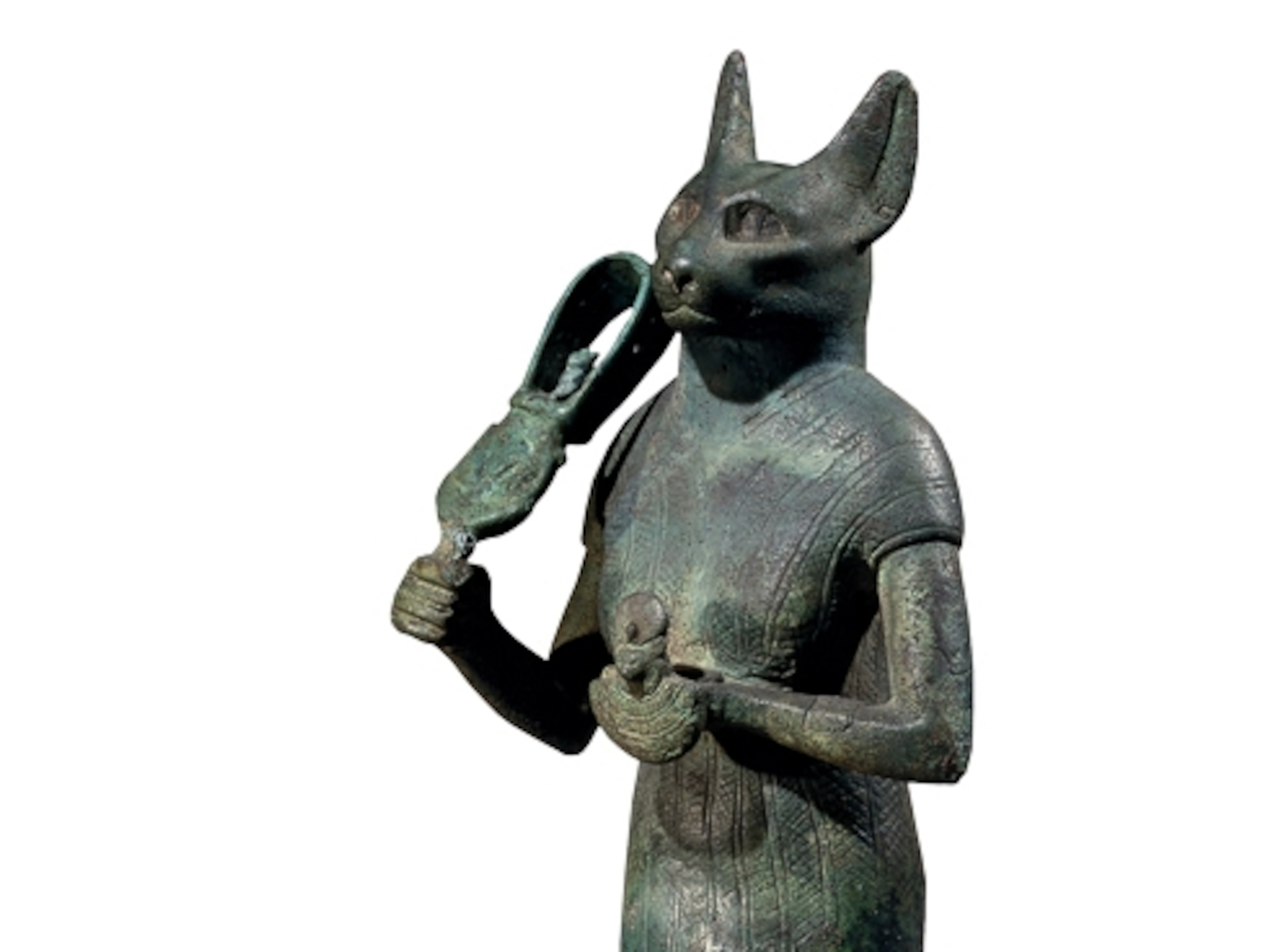

Sometimes confused with Sekhmet, another feline goddess was Bastet, whose cult was centered in Bubastis in lower Egypt. Sometimes depicted as Mau, a divine cat manifestation of Re, she is shown, knife in paw, slaying an evil snake, Apophis. Fierce and friendly, these two feline goddesses became associated with each other, embodying the contradictions of cats’ personalities. In time, compensating for Sekhmet’s fury, Bastet became her binary opposite, representing a gentle, nurturing side.

Divine favor

To win favor with their animal-associated divinities, ancient Egyptians would often turn to their mortal counterparts. Mummified birds and beasts have been found by the thousands at archaeological sites across Egypt. Many were considered votive objects and offered by pilgrims at local temples during religious festivals.

In 2018 archaeologists found dozens of cat mummies and 100 statues of Bastet in a 4,500-year-old tomb in Saqqara. Mummified ibises, the bird associated with Thoth, god of wisdom and writing, were found by the scores at Abydos, the burial ground of Egypt’s earliest rulers. Archaeologists are still finding large numbers of these mummified birds in sites across Egypt.

By the end of the Ptolemaic period in the first century B.C., animal cults’ popularity began to fall out of favor. During Roman rule and the expansion of Christianity into Egypt, the old gods were abandoned. Today new discoveries and the iconic artifacts of ancient Egypt are a reminder of a time that lasted three millennia, in which an animal’s power, grace, and strength were worshipped.