America's first investigative journalist got her start in an asylum

Trailblazer Nellie Bly first went undercover in a New York psychiatric hospital in 1887, when she exposed its horrific conditions.

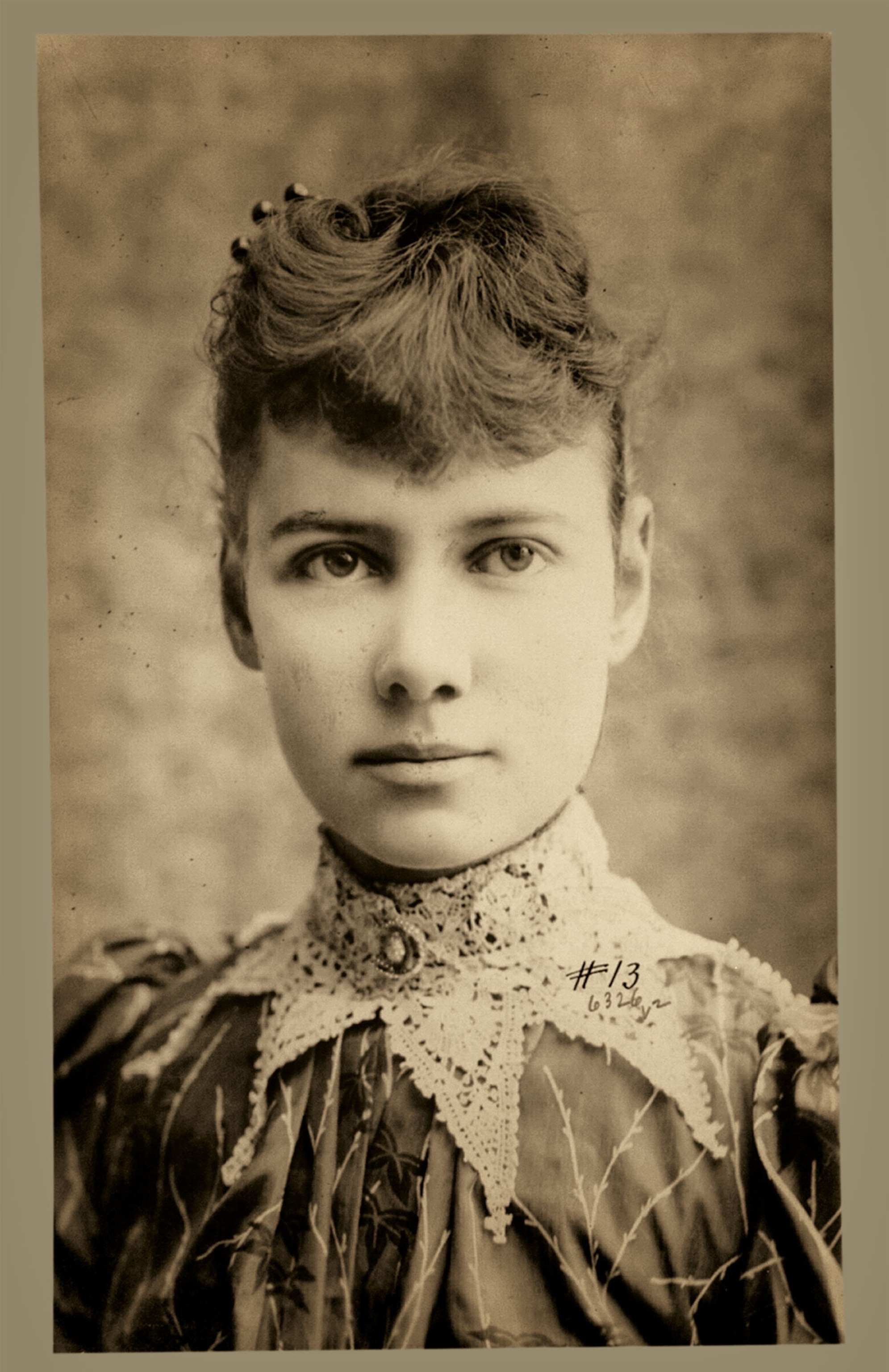

In 1885 the Pittsburgh Dispatch published an article entitled “What Girls Are Good For,” which claimed a working woman was “a monstrosity.” The feature provoked a fiery rebuke from a 21-year-old reader, Elizabeth Jane Cochran, whose argument so impressed the editor that he published an advertisement asking the author to come forward so he could meet her.

She did, and he hired her on the spot, her first article appearing under the name “Orphan Girl.” Soon after, she changed her pen name to the title of a popular song by Pittsburgh songwriter Stephen Foster, and so “Nellie Bly” was born—a name forever associated with her pioneering role in investigative journalism.

In the course of her life, she spotlighted social ills and corruption, often at great personal risk, resulting in important reforms. Distinguishing herself in the almost exclusively male world of late 19th-century journalism, she broke new ground for women in the field.

Cub reporter

Bly—who would refer to herself by her pen name, even in her private life—had originally written as “Orphan Girl” in a reference to her difficult upbringing. Born in 1864 near Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, she grew up in relative comfort until her father’s death when she was six years old. Money became tight, especially after her mother’s abusive second marriage ended in divorce. At 15, Bly ended her formal education, for lack of funds, to run a boardinghouse with her mother for five years. These years of struggle fed her ambition to succeed and a commitment as a journalist to call attention to the hardships of working-class families.

Despite clinching her job on the Dispatch, Bly resented being restricted to writing only for the women’s section of the paper. Frustrated, she went to Mexico alone to work as a correspondent, a virtually unheard-of step for a woman in the 1880s. She covered a range of topics, but those that singled out corruption and exploitation of peasants and workers provoked the ire of the authoritarian government. She was forced to leave to avoid arrest, and back in Pittsburgh found herself reassigned to the women’s section at the Dispatch. Disillusioned, she decided to leave for the big leagues: New York. (These women photojournalists paved the way for future generations of National Geographic photographers.)

Fighting for Equality

After losing her father at age six, Nellie Bly learned to be aggressive, bold, and self-reliant. She also realized early on that despite her abilities, she faced greater obstacles in the workplace than her brothers, who landed their jobs with minimal education. This unfairness prompted her to address the discrimination women faced. In her first article for the Pittsburgh Dispatch, she made an example of a boss who hired a competent woman but, “as she was just a girl,” paid her less than half that of her male co-workers. “There are those who would call this equality,” she wrote sardonically.

Going undercover

Bly arrived in the metropolis at a dramatic time for journalism: New York newspapers were looking for creative ways to increase their circulation with sensational stories to grab readers. After allegedly bluffing her way into their offices, Bly secured a position at the New York World, whose owner Joseph Pulitzer had a meaty assignment lined up for his new reporter.

Pulitzer assigned a story in which Bly would pretend to be mentally ill to get herself committed to the New York City Lunatic Asylum at Blackwell’s Island (now Roosevelt Island) in New York’s East River. She would then write an exposé of conditions in the women’s ward. “How will they get me out?” she asked him. “First get in,” he said.

Bly moved to a boardinghouse and began her performance. Posing as a Cuban immigrant named “Nellie Brown,” she wandered the house, ranted, and yelled. The police were called, and doctors certified that she was “demented.” A judge had her admitted to Bellevue Hospital psychiatric ward, where the initial diagnosis was confirmed, and she was then transferred to the wards on Blackwell’s Island.

Bly quickly observed that the mentally ill lived alongside other women who were institutionalized there despite being healthy. Some were recent immigrants caught up in the legal system and unable to communicate, while others were committed simply for being poor, with no family to support them. To Bly, the asylum seemed less a hospital than a warehouse for the unfortunate. (Here's how Ellis Island shepherded millions of immigrants into America.)

Built for 1,000 patients, it held 1,600 with only 16 doctors and ill-trained, often brutal, staff. Food and sanitary conditions were horrific. Worse still, none of the women were given the chance to prove their sanity. “Compare this with a criminal, who is given every chance to prove his innocence,” she would write.

After 10 days, the newspaper’s lawyer arranged her release. Her account of the experience, published in two parts by the World in October 1887, shocked the public and triggered a grand jury investigation, which led to increased funding and improved conditions for patients in psychiatric wards.

One of the first examples of undercover investigation in American journalism, the two-part report made Bly a star. From then on, headlines for her stories at the World often used her name as a selling point, such as “Nellie Bly Buys a Baby,” an investigation into the sale of infants, or “Nellie Bly Tells How It Feels to Be a White Slave,” about underpaid women workers in a box factory. In another story, she set up a lobbyist who bribed state legislators on behalf of clients. “I was a lobbyist last week,” the story began. “I went up to Albany to catch a professional briber in the act. I did so.” The lobbyist fled town.

Globe-trotter

Recognizing the huge commercial success of Bly’s work to date, other American newspapers scrambled to hire their own “stunt girls.” But Bly stood out because “along with derring-do and excitement, she had a social agenda that was always present in her work,” according to Brooke Kroeger, author of Nellie Bly: Daredevil, Reporter, Feminist.

Racing Around the World

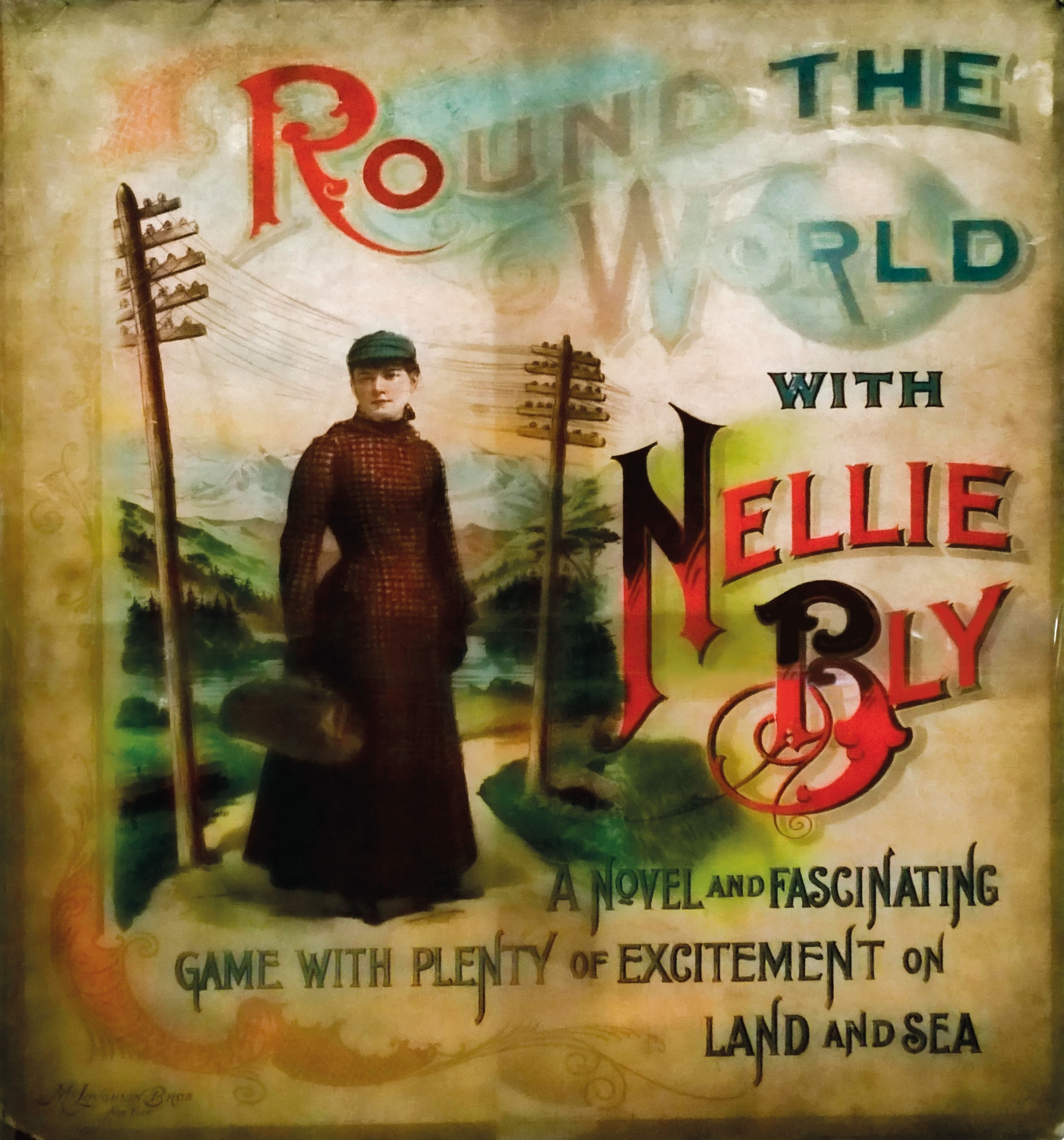

Nellie Bly managed to circumnavigate the world in just 72 days, eight less than Jules Verne’s fictitious hero, Phileas Fogg, who inspired the feat. On train, ship, rickshaw, horse, and donkey, Nellie passed through London, Amiens, Suez, Singapore, Hong Kong, Yokohama, and San Francisco before returning to New Jersey in 1890. Readers of the New York World followed her adventures daily and placed bets on the number of days it would take. Bly defeated journalist Elizabeth Bisland, sent by the magazine Cosmopolitan, in a race that boosted the World’s readership and advertising revenues.

In fall 1889, as the World opened new headquarters, Pulitzer wanted a big, attention-grabbing story. Bly proposed an around-the-world race to break the fictional record set by Phileas Fogg in Jules Verne’s 1873 novel Around the World in Eighty Days. Pulitzer thought the idea better suited to a man. “Very well,” Bly said, “Start the man, and I’ll start the same day for some other newspaper and beat him.” Pulitzer wisely reconsidered.

Bly set off from Hoboken, New Jersey, on November 14, 1889. Among her many adventures was a meeting with Jules Verne in France. Verne, age 61, told her: “If you do it in 79 days, I shall applaud with both hands.” She would win his applause handily, completing the trip in a record-breaking 72 days. When she stepped off the train in Jersey City, thousands cheered her. At 25, she was America’s first celebrity journalist. (Meet the solo women sailors that race around the world.)

Her book Around the World in Seventy Two Days was published soon after, joining her other books based on her reporting: Ten Days in a Madhouse (1887) and Six Months in Mexico (1888). Her literary success did not carry over into fiction, however, with the 1889 publication of The Mystery of Central Park, being her one and only novel.

In 1895, at 30, Bly married 72-year-old Robert Seaman, the millionaire manufacturer of kitchen enamelware and other products at Iron Clad Manufacturing Co. She did some part-time reporting up until his death in 1904, when she began a 10-year hiatus from journalism to run the company. Business thrived; she even took out patents, but embezzling accountants drove the enterprise into bankruptcy.

In 1914 Bly went to Austria, partly to seek financing for her company. During four years there, she became the first woman correspondent on the eastern front during World War I. Back in New York, she continued writing for the press, using her column to help people find work and housing. (This is why it's still difficult for women to travel the globe.)

In January 1922 Bly died of pneumonia in New York; she was 57 years old. In the decades following her death, investigative journalism and reporting have changed drastically. Bly’s persistence and pioneering opened up new frontiers for news and the people who report it.