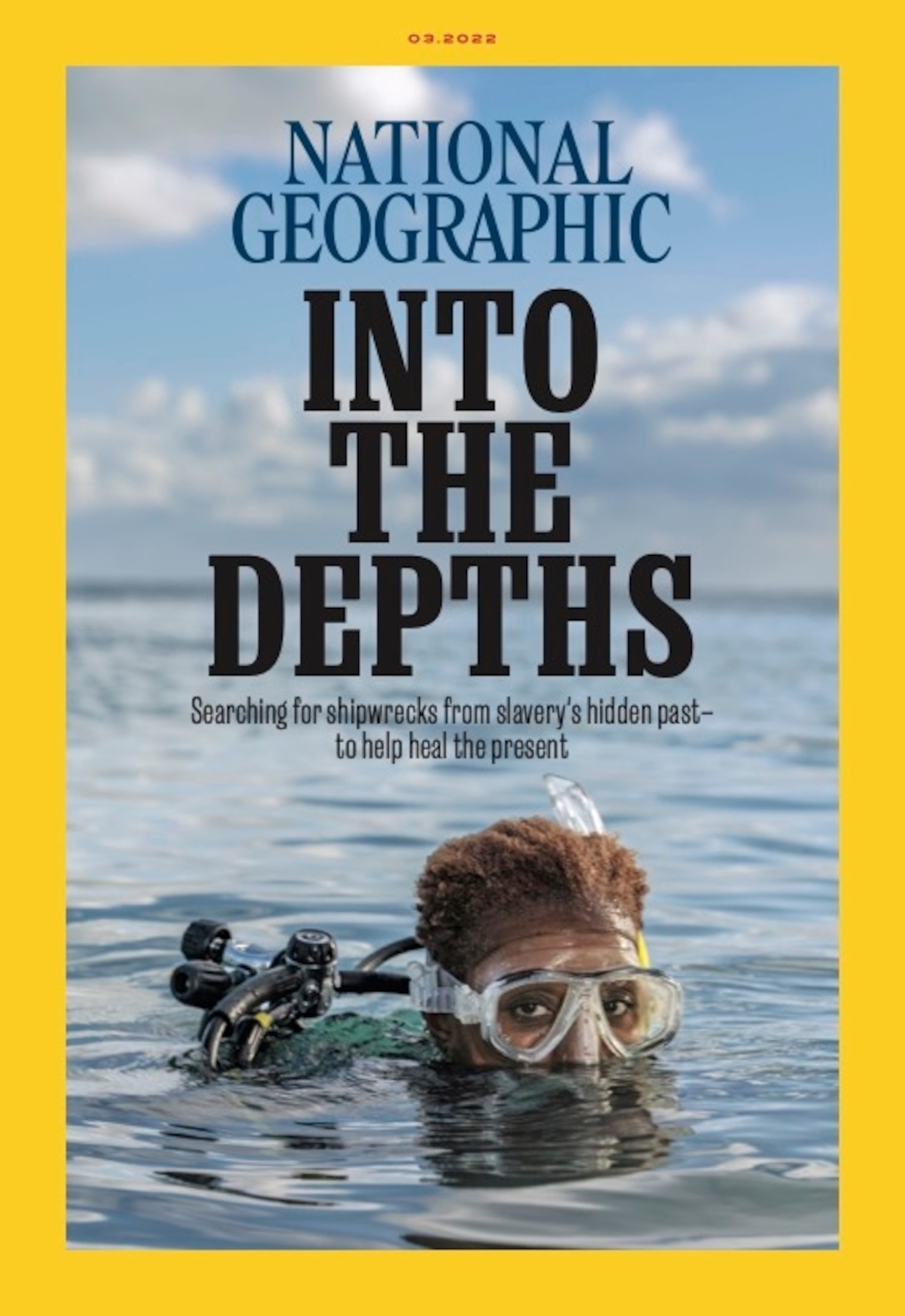

Tara Roberts is surfacing human stories from the shipwrecks that killed enslaved Africans

The storyteller joins a team of African American divers on their worldwide quest to shed light on the untold history of the slave trade.

National Geographic Explorer in Residence Tara Roberts peers into the depths of the Atlantic from the boat’s edge, hovering around the open water of the Florida Keys. She leans in and plunges beneath the shadowy surface, disappearing with her fellow divers into a bubbly abyss. They descend toward a hidden history etched into the sandy floor.

Somewhere below, buried by the passage of time and the sea, lies a wreck — one of an estimated 1,000 ships carrying captive African people that wrecked before reaching shore between the 16th and 19th centuries. The Guerrero was a Spanish slave ship seized by the British Royal Navy in 1827. While illegally transporting 561 Africans to Cuba (trading captive Africans between nations had been made illegal by Spain, England, and the Americas, though domestic trade of enslaved people continued), the vessel was chased by the British and crashed resulting in 41 deaths. Five hundred and twenty African people survived. The Guerrero was swallowed by the deep blue.

The exact location of the vessel’s remains around present day Biscayne National Park has yet to be determined, and for 25 years, a team of African American divers, assembled as the nonprofit Diving With a Purpose (DWP), have been looking for it in their quest to shed light on the 400-year-long slave trade. Since 2018, Roberts has been diving with them in their mission to surface human stories of the souls lost at sea.

“I think of the Guerrero Africans, who must have worked together to survive. I want to believe that those 520 survivors leaned on one another to make it through what was probably the most terrifying experience of their lives,” writes Roberts in the latest installment of her storytelling project about DWP, “Written in the Waters: A Memoir of History, Home and Belonging", which was published in January.

Since its founding, the DWP crew has helped uncover 18 sites in an effort to memorialize lives lost and connect with their ancestors. In the process, they find community.

“The truth is, I can’t do this work underwater alone. I just don’t have the skills,” Roberts continues. “And the bigger truth is that none of us can do the work above the surface without leaning heavily on each other.”

Roberts, a journalist by training who offers transparency around what she calls her “curvy path” to collaborating with DWP, reframes the origins of African people in the Americas with empathy, complexity and a focus on their humanity through her storytelling.

The Atlanta-raised Roberts enjoyed burying herself in stories as a kid. Over and over again, she wandered the fantasy realm with books while growing up. Through Madeleine L’Engle’s “A Wrinkle in Time,” her favorite book, she disappeared into adventure. “I wanted to be a Charles Wallace.” She longed for the opportunity of an unexpected journey. The possibility of a life beyond the one in front of her.

“I loved the idea of being called to be bigger than you think you are.”

Roberts had never dived seriously, “or necessarily thought of myself as a diver” prior to contemplating joining DWP. Before descending toward the suspected site of the Guerrero, she became scuba certified and participated in the DWP certification program, for which she had to complete 30 ocean dives to be eligible.

Since joining the league of primarily Black divers with DWP, she produced a six-part podcast series, “Into the Depths” with National Geographic, and has been featured in National Geographic’s film “Clotilda: The Return Home,” a documentary series about the descendants of Clotilda, the last known American slave ship. She was named a Rolex National Geographic Explorer of the Year for her in-depth storytelling. All her stories, she says, have been a way to recount the work of the DWP community and her own transformative experience.

“To me, being down there under the waves, I feel fierce about it. I feel ‘let’s do this. Let's find this history and tell the story,’’’ Roberts says.

At least 1.8 million African people perished at sea. Between 500 and 1,000 ships sank. An estimated 12.5 million people were forcibly transported on ships across the Atlantic, trafficked around from Europe to Africa, Africa to the Americas, and the Americas to Europe — the Middle Passage. Shackled together below deck, they were transported on journeys averaging 60 days. More than ten million people survived to disembark.

‘It’s the curvy path’

This whole journey started because Roberts’ took a leap of faith.

As a media professional, Roberts has worked for CosmoGirl, Essence, Ebony and Heart & Soul magazines. She eventually started her own entrepreneurial publishing nonprofit endeavors, sharing stories of women changemakers around the world. She followed a job to D.C. in 2016, and visited the newly-inaugurated National Museum of African American History and Culture.

“That’s how I saw the photograph that changed everything.”

Had she not moved to D.C., she says she may not have visited the museum. And had she visited as tourist and not a resident, she may not have meandered the museum’s halls with such leisure, and she may not have taken notice of the details of one portrait in particular.

“I think all of those things were leading me to this moment. It’s all connected, it’s the curvy path,” says Roberts.

The photo of a crew of Black women in wet suits aboard a boat was her first encounter with DWP. It beckoned her to follow. She phoned the co-founder, Kenneth Steward. She pledged to join them.

“The universe works in strange ways,” says Roberts, reflecting on how she grew up nowhere near an ocean.

“I imagined the divers. And then I imagined myself as one of them. I didn’t know it would lead anywhere, I just knew I wanted to know more.”

So she quit her job to follow the divers and help tell their stories.

A way of honoring ancestors

Roberts’ path shows a nuanced story as she ricochets from peaks and valleys toward a calling. It’s the detail and complexity she aims for in the narratives she uncovers in her work.

“Think about the Clotilda shipwreck… that’s a story that no one would know if the Clotilda descendants hadn’t been like ‘oh, we have saved artifacts and the stories of our ancestors, we’re not going to let anyone forget them.’”

The Clotilda, Roberts reflects, represents a uniquely complete story. The vessel sailed in 1860, illegally transporting captive Africans from present-day Benin to Mobile, Alabama. It is said a wealthy landowner by the name of Timothy Meaher challenged Northern businessmen with a thousand-dollar wager, claiming he could slip African people past federal officials and into Mobile Bay.

The ship itself is remarkably well-preserved in the muddy freshwater of Alabama’s Mobile River, compared to other wrecks, which are often shattered on the sea floor, coalesced into the marine ecosystem, or dissolved over time. And the Clotilda’s African survivors, who were removed from the ship as the captain burned it to hide evidence, established the community of Africatown in Mobile once they were freed from enslavement after the Civil War. They neighborhood they established eventually grew into a community of tens of thousands, including their descendants. It still exists today and which continues to honor the stories of those ancestors from the nation’s last known slave ship.

“That's often not what you get around stories that involve African Americans," Roberts says. "Most of us cannot trace our histories all the way back to a slave ship or to a particular country in Africa because the records of the enslaved were not recorded in detail. So it’s incredible and very powerful that these descendants know the actual stories of their ancestors that came from Africa."

For the podcast Roberts interviewed not only the descendants of those on slave ships, but close to 100 other historians, archaeologists and community members about their unique relationships to this history. “By the end of it, I realized that these weren’t just stories of death, that these were stories of life, too,” Roberts recalls.

“It’s a complicated history, but that’s the way history is supposed to be.”

The Christianus Quintus and Federicus Quartus wreck site were the first dive Roberts recalls leaving an impression on her, “I felt more than anything a sense of agency and power,” she says.

In 1710 two Danish slave ships, the Christianus Quintus and Fredericus Quartus went down in the Atlantic. Some 40,000 Danish bricks signaled the wreckage to experts in the 1970s, despite their considerable decomposition. A cannon and large anchor are still laid out as artifacts on the seabed. After quashing a revolt, the two vessels veered off course, missing their St. Thomas destinations by over a thousand miles, the crews mutinied, freed approximately 650 captive people due to dwindling resources, and scuttled the vessels which now lie in the ocean sands of present-day Costa Rica.

As the site came into view for Roberts, “I felt, ‘I see you and I’m going to help bring this story back to human memory. We are going to help make sure you are honored, not forgotten.’”

Diving With a Purpose is rewriting the story of African American history.

“Most of the ships were built in the 16th and the 17th centuries, when building material was wood. So when they wreck, they splinter on the floor and the ocean reclaims them,” Roberts explains. So the divers’ trained eyes look for patterns that are unnatural. “Perfect circles, wood fastened to metal, right angles. Nature doesn’t tend to make things in right angles.”

Less than one percent of maritime archaeologists in North America are of African descent. “Diving With a Purpose is rewriting the story of African American history,” says Roberts.

Diving has led her to a personal, terrestrial investigation of her own DNA. She recounts the experience in the podcast; how she traced her ancestry to Benin and Togo in Africa. She hiked the slave trail in Benin, she walked around “the tree of forgetfulness” seven times, as captive women would have been made to as a ritual to leave their identity behind, and become a blank canvas. She stood at the Door of No Return — the last point on the African continent before people were forced onto ships as slaves.

Going forward, she explores the question: “How do we interact with histories of the slave trade and still take care of ourselves?”

A new era of memorialization

Right now, Roberts is developing the next phase of her storytelling, which will branch into memorializing, expanding technical training and broadening engagement opportunities for the public with this historical period.

The future of DWP looks like more certification for swimmers, divers and snorkelers around the world. The DWP community firmly believes anyone can dive.

“I was told early on by one of the divers that ‘there are two kinds of people in the world: people who are divers, and people who are yet to become divers,’” Roberts laughs. But for those who don't want to engage directly with the water, she implores supporters to lean into curiosity, to learn the history, to share stories.

“I think stories are one of the most powerful things around. They give us a chance to empathize with those whose shoes we may never walk in, and who we may never have the chance to know” she says. “I think stories are one of the ways that we can use to really change the world.”

ABOUT THE WRITER

For the National Geographic Society: Natalie Hutchison is a Digital Content Producer for the Society. She believes authentic storytelling wields power to connect people over the shared human experience. In her free time she turns to her paintbrush to create visual snapshots she hopes will inspire hope and empathy.