A new idea to fight brain cancer, and more breakthroughs

Tests track how particles might convey a cancer drug to a brain tumor, archaeologists find mummified macaws, and pharaohs get new digs.

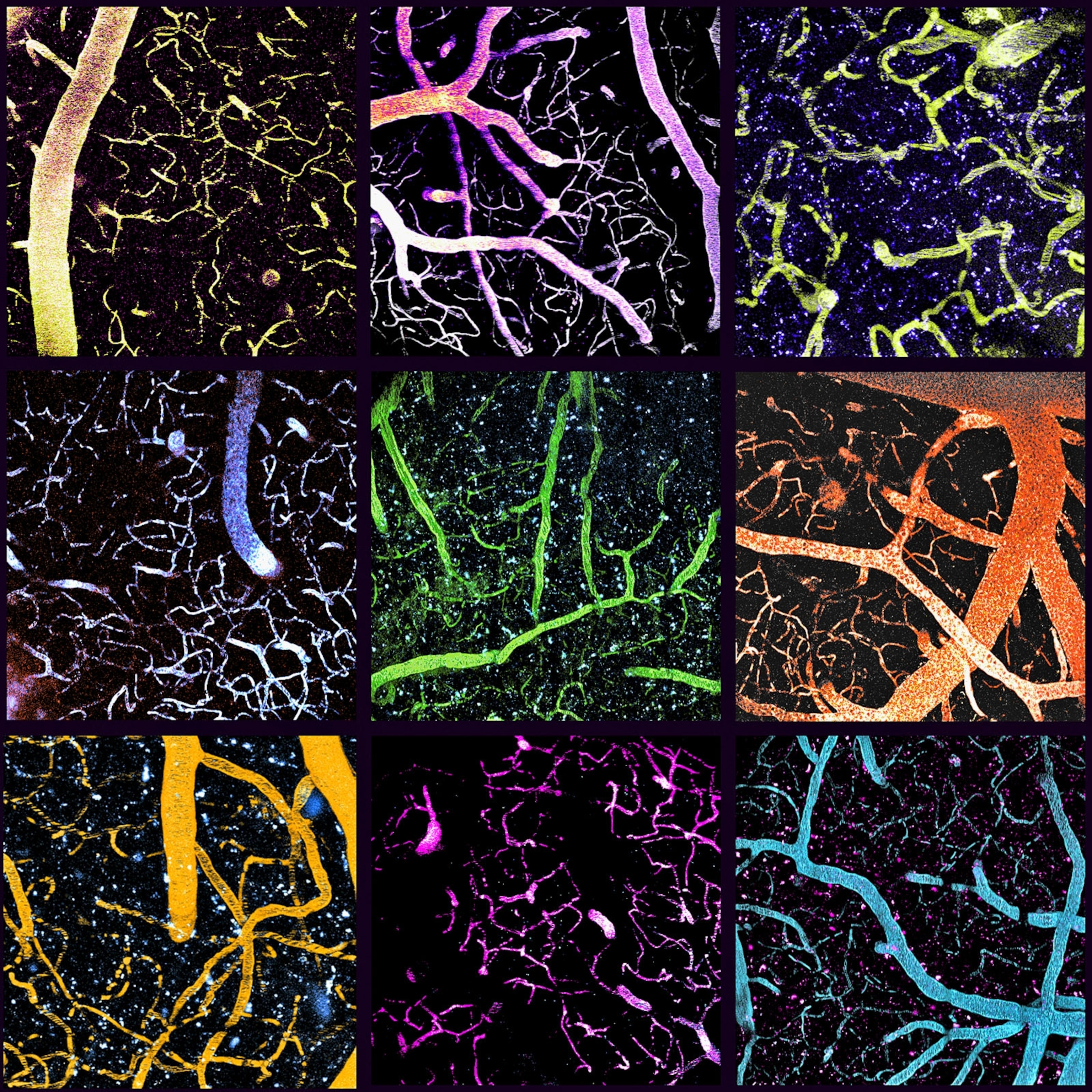

Nano-special delivery

Hundreds of drugs designed to fight glioblastoma multiforme, an aggressive brain cancer, have failed in clinical trials, often because they’re stopped by specialized blood vessels known as the blood-brain barrier. So Joelle Straehla, a postdoctoral fellow in the Hammond Lab at MIT’s Koch Institute for Integrative Cancer Research, is developing nanoparticles that could someday ferry drugs past the barrier and directly to tumors. To test the system, Straehla injects empty nanoparticles and a fluorescent dye into a mouse’s bloodstream as images of the brain are recorded. The dye illuminates the branchlike blood vessels (nine images above). The particles glow in a contrasting hue; if they reach the brain (shown as black), algorithms can detect each glow. In these photos, specks represent several particles clustered in test animals’ healthy cells—suggesting that if particles reach the brain but not a tumor, they might have other uses, like immunotherapy. —Theresa Machemer

Mummified menagerie

Archaeologists excavating the remains of ancient societies in the Atacama Desert in northern Chile have unearthed a menagerie of mummified parrots and macaws. Scholars knew tropical feathers were present in the world’s driest desert and had speculated about their origins. A new study found that the birds likely were captured in the Amazon—over 300 miles away—taken to the Atacama, and raised for their ornate feathers. Why they were mummified remains a mystery—but they were prized as symbols of wealth and status. —Annie Roth

Pharaohs’ new digs

No more contrived displays for the 22 royal mummies—including Queen Hatshepsut (below), one of the few female pharaohs—moved to Cairo’s new National Museum of Egyptian Civilization in a gala parade last spring. Instead, the human remains will lie in dim, tomblike halls with their burial goods. —Tom Mueller

This story appears in the August 2021 issue of National Geographic magazine.