Why we reported on life after death row for the exonerated

Found innocent after wrongful convictions, these people are the ultimate argument against the death penalty, says the photographer who profiled them.

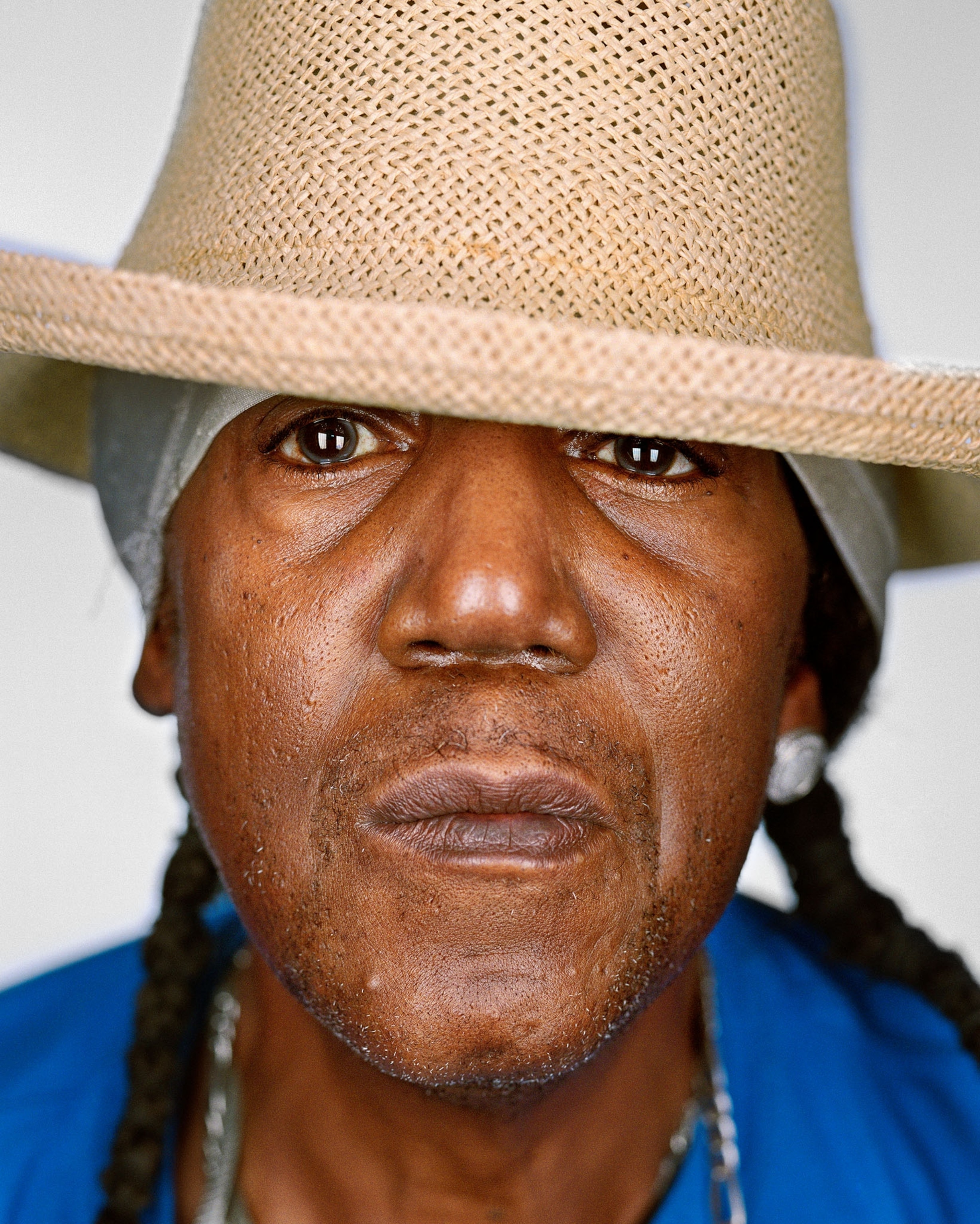

Since 1972, 180 men and two women in the United States have been freed from death row after being found innocent of the crimes for which they were sentenced to die. Martin Schoeller, a longtime National Geographic contributor known for his haunting, close-up portraits, has photographed, filmed, and interviewed 17 of them.

Schoeller brought these photos to us and our colleagues at ABC News (both organizations are owned by The Walt Disney Company). His goal: He wants people to reconsider their support for the death penalty, which today in America can be imposed by 28 states, the federal government, and the military. Schoeller hopes that people who see his photos “feel like ‘This could have been me—and they were sentenced to death for something they didn’t do.’ That’s the reason I did this: To create work that will change some people’s hearts.”

Whether you support or oppose the death penalty, there’s no question that Schoeller’s portraits and stories of exonerated former prisoners are powerful. These people were caught up in a Kafkaesque nightmare, often caused by police or prosecutorial misconduct, or witnesses who lied or were mistaken. Most of the wrongly convicted had poor legal representation; disproportionate numbers of them were people of color, from low-education and low-income backgrounds. They sat on death row, typically in solitary confinement, sometimes for decades. They missed their own parents’ funerals. Their children grew up without them.

Ultimately, they were freed by DNA evidence, better lawyers, or events that caused the truth of their innocence to come out. After all that, most are managing to go on, reclaiming their lives with varying degrees of success.

Schoeller has a unique perspective on how they do it. For another recent project, he has been taking portraits of now elderly survivors of the Holocaust. He’s found that the two groups have something important in common, he told me: “They are able to forgive. There are so many reasons that you can be hateful and mad at people, but you have to have the ability to forgive. Otherwise it just eats you up,” he said. “The people who can’t get to that conclusion emotionally, they don’t make it.”

For most of National Geographic’s 133 years, photography has been central to our mission. Martin Schoeller’s portraits remind us why: Because even in a streaming-media age, still photos can reveal indelibly powerful stories.

Thank you for reading National Geographic.