Silent Streams

Freshwater animals are vanishing faster than those on land or at sea. But captive-breeding programs hold out hope.

This is a strange sort of ark: a brick warehouse in Knoxville, Tennessee. Not only will the thing never float, but the life-changing flood is all inside, where water pours day and night from a maze of pipes into 600 glass aquariums and plastic tubs stacked to the ceiling. The passengers, most just a few inches long, are fish: madtoms and darters, topminnows and chub. For them the carefully filtered, aerated water offers the breath of life, whereas their natural homes—streams and rivers in the southeastern United States—are choked by dams and clouded with pollutants. The fish aboard the ark are among the last of their kind.

At the helm, sharing the role of Noah, are J. R. Shute of North Carolina and Pat Rakes of Arkansas, who met at graduate school in the mid-1980s. They've been splashing around streams and keeping aquariums since they were boys. Now they've managed to transform a boyhood passion into an unusual profession. Freshwater animals are under siege all over the planet, and the species-rich Southeast is no exception. At their Knoxville nonprofit, Conservation Fisheries, Inc. (CFI), Shute and Rakes are trying to keep some of the rarest species alive.

This is not like raising goldfish or guppies. Among the ark's passengers is the diamond darter, an imperiled sandbar dweller; it has proved so sensitive to disturbance that the biologists observe it in its aquarium only through a remote video monitor. Another darter, the Conasauga logperch, swims in a tank nearby. Its only known habitat is the Conasauga River in Georgia and Tennessee, whose waters have long been polluted and silted up by farms and factories. The Conasauga might still hold 200 of these fish, or it might not, but the three recent arrivals here are the only ones in captivity. Everyone at CFI is hoping they don't turn out to be the same sex so they can pair off. No effort will be spared to give them the arrangement of sand, gravel, or little rock shelters that might inspire intimate relations.

Capturing the fish in the first place is just as challenging. In dive masks and bulky dry suits, talking through snorkels and wearing fish-scooping nets like hats because they need both hands free to pull themselves along the bottom, Shute and Rakes are a distinctive presence in a river. They often snorkel with flashlights at night, when some fish are more active. Once, as they splashed past a dark campground, they heard somebody holler, "Dang! Looks like a bunch of big bullfrogs with headlights."

The goal is to have seed stock ready to restore the fish to a river, if and when society restores that river to its clean, free-flowing state. It hasn't happened yet to the Conasauga, but it is happening in other streams. These days Shute and Rakes find themselves not just capturing fish to bring aboard the ark but tracking the progress of fish they have already returned to the wild. "It's a big, natural experiment, and we're learning as we go," Rakes said. "I feel very lucky to be doing something I care about so much."

Lakes, swamps, and rivers make up less than 0.3 percent of fresh water and less than .01 percent of all the water on Earth. Yet these waters are home to as many as 126,000 of the world's animal species, including snails, mussels, crocodiles, turtles, amphibians, and fish. Almost half the 30,000 known species of fish live in lakes and rivers, and many aren't doing well; in North America, for instance, 39 percent of freshwater fish are imperiled, up from 20 percent only a few decades ago. Freshwater animals in general are disappearing at a rate four to six times as fast as animals on land or at sea. In the United States nearly half the 573 animals on the threatened and endangered list are freshwater species.

That's because freshwater ecosystems are so closely linked to human activity. Industry and agriculture are concentrated alongside flowing waters, and sooner or later the residue of virtually everything we do winds up running down the nearest creek—if we haven't dried up the creek first. In the southwestern U.S., as in other arid parts of the world, wildlife must compete for water with a burgeoning human population. Neither the Rio Grande nor the mighty Colorado is more than a trickle at its mouth today.

But it is the American Southeast that stands out as a world center of freshwater-species diversity, especially the southern Appalachian Mountains. Carved up into countless hills and hollows that are aglimmer with springs, riffles, rapids, smooth glides, and pools, the highly eroded mountains provided the isolated niches in which freshwater creatures could evolve into a multitude of forms. They also escaped the Ice Age glaciers that bulldozed much of the continent farther north. The result: The Southeast holds the grandest array of freshwater mussels on Earth; North America's premier collection of freshwater snails, crayfish, and turtles; and nearly 700 of the approximately 1,000 species and subspecies of U.S. freshwater fish.

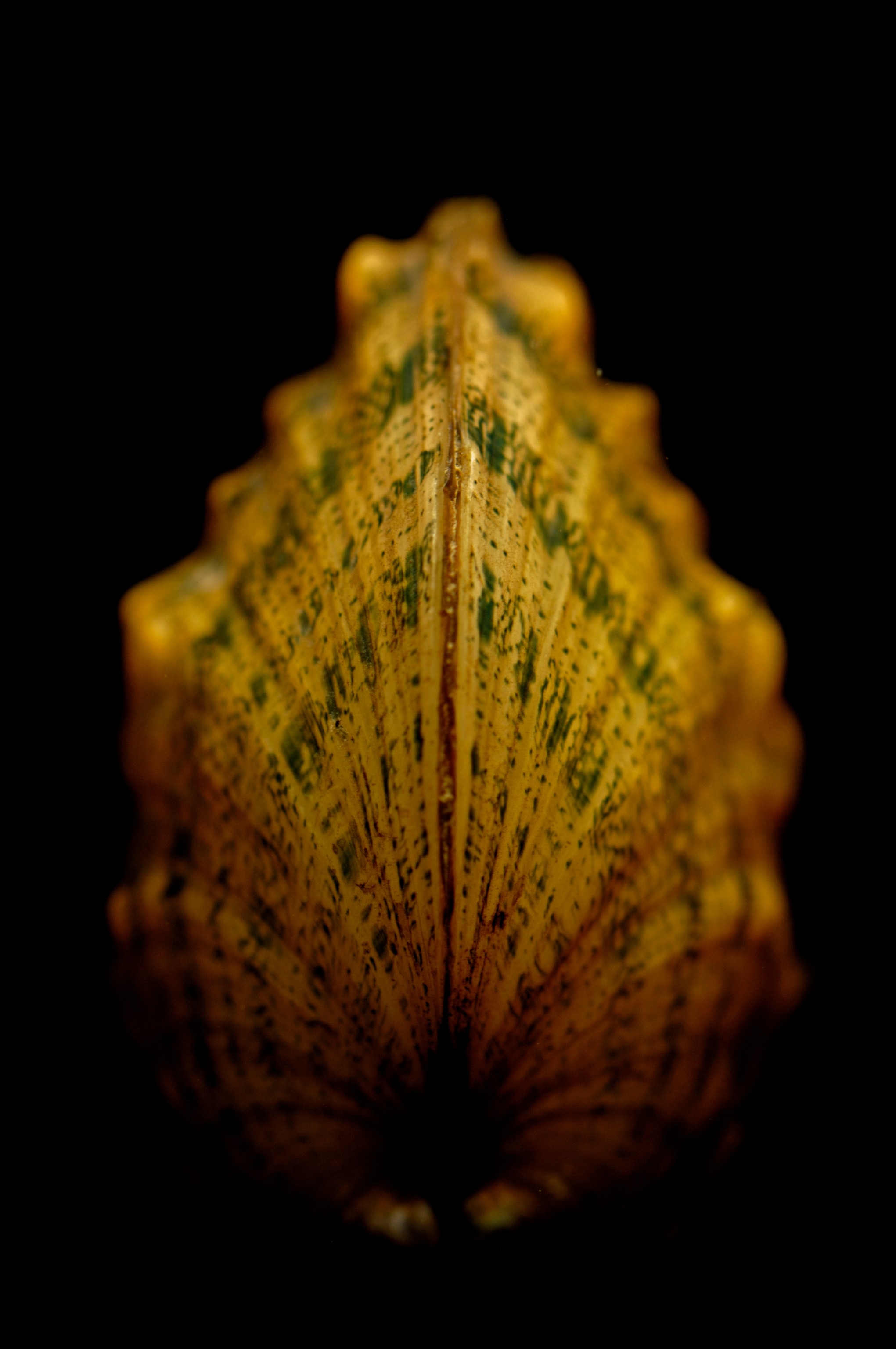

Like most freshwater fish, those of the Southeast tend to be small and subdued in coloring—for most of the year. If you dunk your head in during spring or summer, though, when the males assume breeding hues, you might think you were near a coral reef. Christmas darters look like swimming red-garlanded trees; holiday darters and lipstick darters are striped and flecked in turquoise and orange. Male lollypop darters have knobs along the top of their dorsal fin that swell large and bright yellow—presumably to mimic eggs and inspire females to lay some. Behaviors can be equally striking. Male madtoms—finger-length catfish with barbels extending like whiskers from around their mouths—take eggs into their mouths to clean them. Some male darters do that by fanning water over the eggs, which also supplies the eggs with oxygen. The Conasauga logperch, barely five inches long, uses its snout like a crowbar to flip pebbles in search of food.

With so many streams drowned beneath reservoirs or smothered by sediments from human activities or laden with harmful chemicals, nearly a third of the Southeast's fish are at risk of vanishing, many within a matter of years. CFI isn't the only outfit working to preserve them. The Tennessee Aquarium in Chattanooga, other private facilities, and state and federal wildlife agencies have efforts under way as well. It's mostly thankless work. A group of independent scientists, the Southeastern Fishes Council, put together a list they call the desperate dozen—"the 12 fish most likely to become extinct soon," said Anna George, chief research scientist at the Tennessee Aquarium. "The public has never heard of most of them."

One exception is the Alabama sturgeon, which is, or was, up to 30 inches long. Its population was decimated in the past century by commercial fishing and dams that sealed off its migratory spawning routes. This sturgeon may now be the most endangered fish in the U.S. Intensive searches have turned up exactly three since it was officially protected in 2000. The last one caught, in 2007, was given a tracking device and followed daily for two years on the chance it would lead to others. It never did, and there are no Alabama sturgeons in captivity.

In general, though, the endangered southeastern fish are of no economic importance. In some places that's precisely why they were eliminated. Tennessee's Abrams Creek, which winds for just 25 miles, mostly through Great Smoky Mountains National Park, used to hold nearly 70 species of native fish. (In contrast, the Columbia and Colorado river systems, which drain most of the American West, support only 54 species between them.) But park officials decided in 1957 to poison the native fish and stock the stream with non-native trout for sportfishing. They didn't want all those little local "baitfish" competing with young trout for food. Before long, Abrams Creek had lost nearly half of its original fish species.

Since then, however, attitudes among wildlife managers have changed. Now they want their world-class menagerie of little fish back.

Abrams Creek was running clear and cool, shaded by tulip poplars, pawpaws, and pines, on the day I belly flopped in with Shute and Rakes last fall. Flotillas of crimson leaves sailed by downstream, and stripe-necked musk turtles swam over to survey us as we counted fish. From 1986 to 2002, Shute and Rakes toted bucketfuls of fish from the Knoxville ark to Abrams Creek; now they return each year to monitor the results. It's just one of more than 30 streams they are working in. Since the 1950s and '60s, attitudes—and laws—have changed outside the national parks as well. Southeastern rivers are as dammed up as ever, but after a long era of relentless logging, coal mining, and discharging from factory and sewage pipes, environmental laws have cleaned them enough that in some places, ark-raised fish can be released to test the waters.

The success stories are starting to come in. The Powell River, a tributary of the Tennessee, was devastated in 1996 by spills of coal-mine sludge, which, among other things, drastically shrank the range of the threatened yellowfin madtom. But CFI has reintroduced the fish and helped to expand the range again. "Lately we've been finding them in 35 miles of the Powell," Rakes said. "They're doing great." And on the afternoon last fall when the CFI team and I floated down a stretch of the river in Virginia, we had plenty of other company: at least a dozen species, including chub, darters, minnows, and shiners, beaming after bits of food in the eddies that formed behind us.

Yellowfin madtoms are doing well in Abrams Creek too, as are the smoky madtoms, an endangered species that CFI also reintroduced. The spotfin chub didn't take, but Citico darters are thriving after nine years of restocking; in one hour last fall the CFI team counted 47. Later, standing among burbling aquariums in the Knoxville warehouse, Shute talked about how he had seen much worse places than Abrams Creek and about why he remains optimistic nonetheless. He described the Pigeon River, which flows from North Carolina into Tennessee.

"It was the worst of the worst around here," he said. "But the company dumping in toxic chemicals cleaned up its act. Communities improved their wastewater outflows, and we've started to reintroduce tangerine darters.

"You keep the last fish in an ark because you never know when a river might come back," Shute went on. "If the Pigeon could, any river can. They'll have to drag me out kicking and screaming before I give up."