Scary, Squishy, Brainless, Beautiful: Inside the World of Jellyfish

They aren’t actually fish. They can make copies of themselves. And some older ones can become young again.

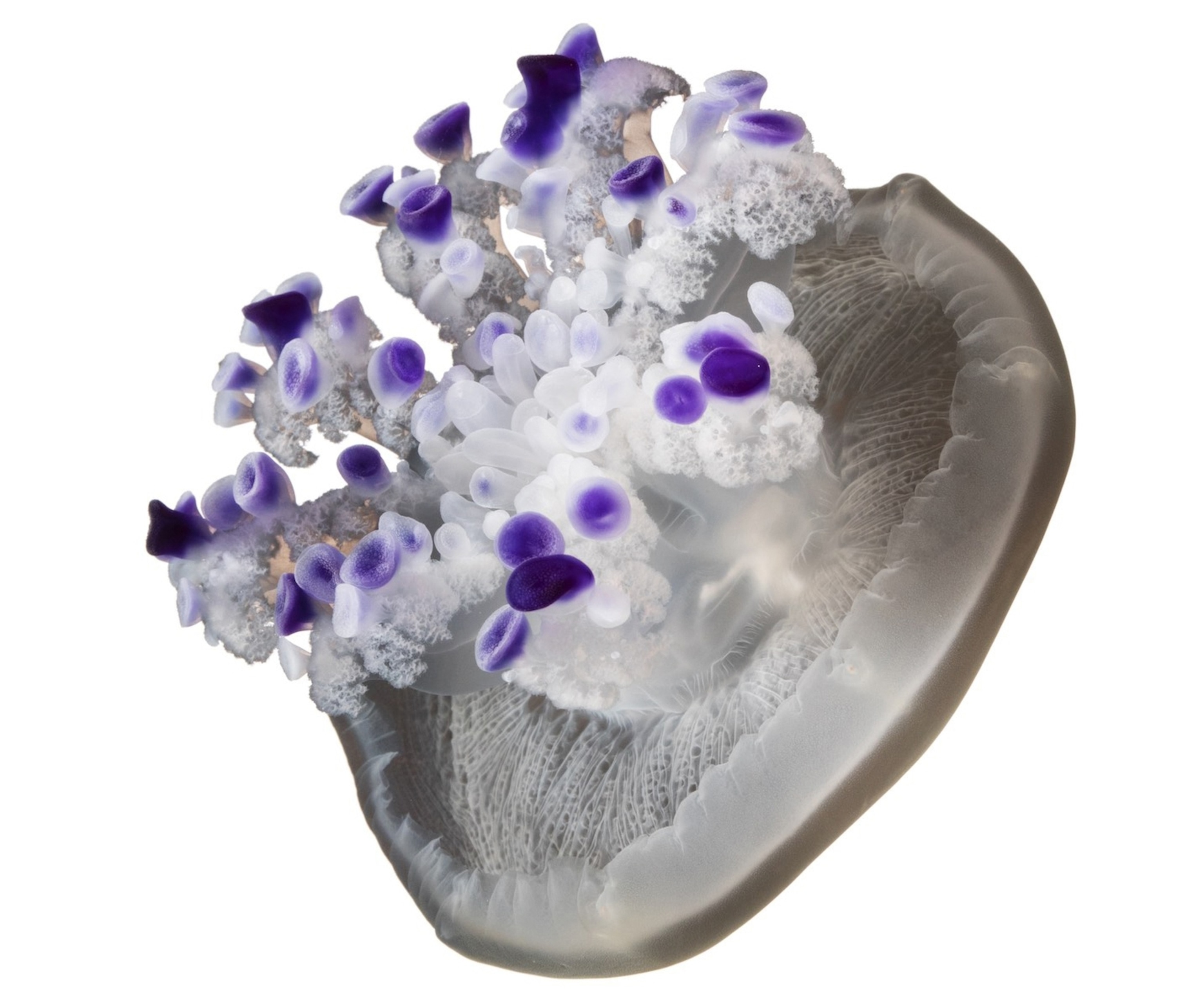

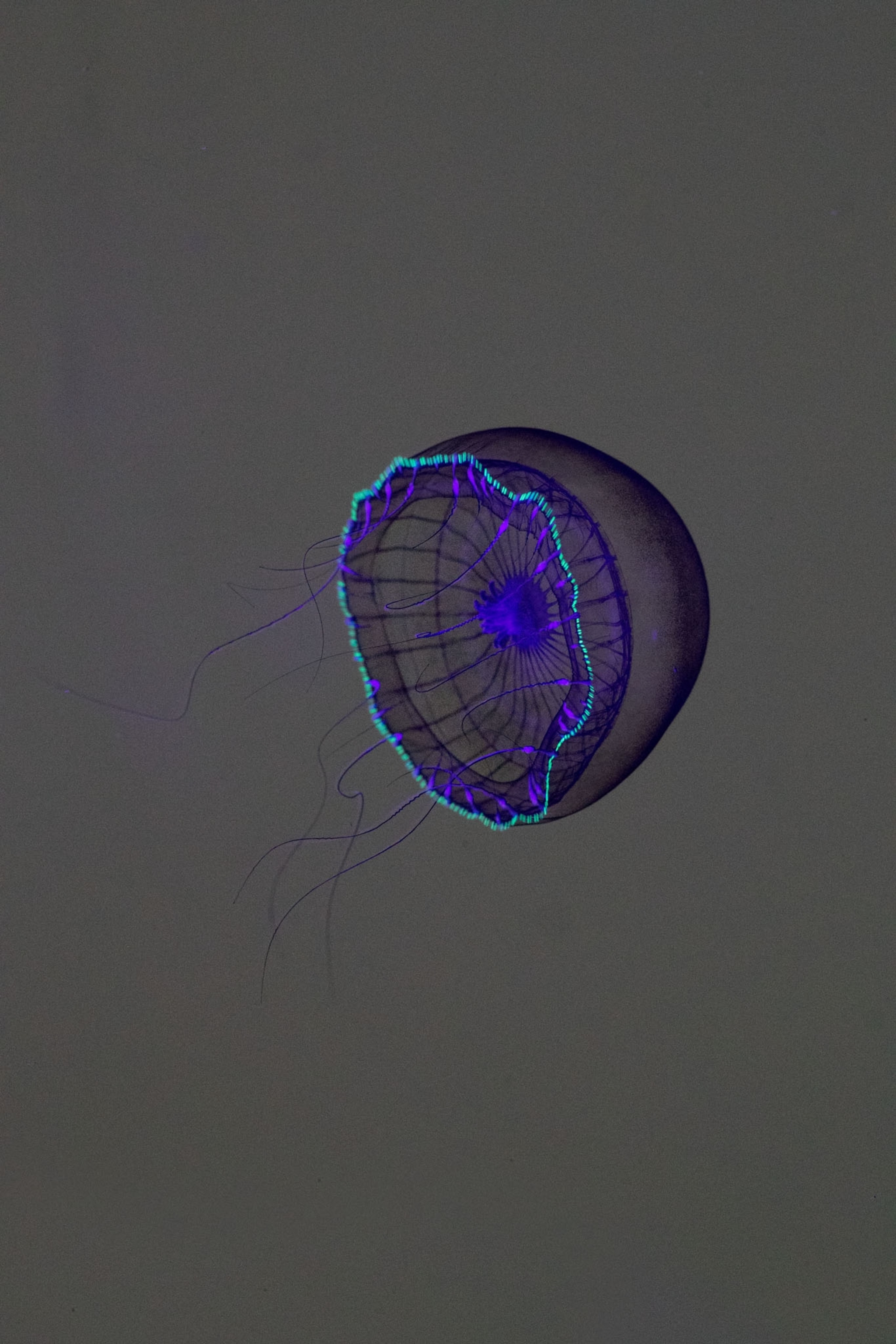

Moon jellies, which are found in shallow bays around the world, look like small, not entirely friendly ghosts.

They have translucent bells fringed with pale tentacles, and as they pulse along, it almost seems as if the water itself has come alive. At the National Aquarium in Baltimore, when visitors are invited to touch moon jellies, their first reaction is usually fear. Assured the jellies won’t hurt them, the visitors roll up their sleeves and hesitantly reach into the tank.

“They’re squishy!” I hear one boy squeal.

“They’re cool!” a girl exclaims.

“I think they’re just mesmerizing,” Jennie Janssen, the assistant curator who oversees the care of the aquarium’s jellyfish, tells me. “They don’t have a brain, and yet they’re able to survive—to thrive—generation after generation.”

Scary, squishy, cool, brainless, mesmerizing—jellyfish are all of these and a whole lot more. Anatomically they’re relatively simple animals; they lack not just brains, but also blood and bones, and possess only rudimentary sense organs. Despite their name, jellyfish aren’t, of course, fish. In fact they aren’t any one thing.

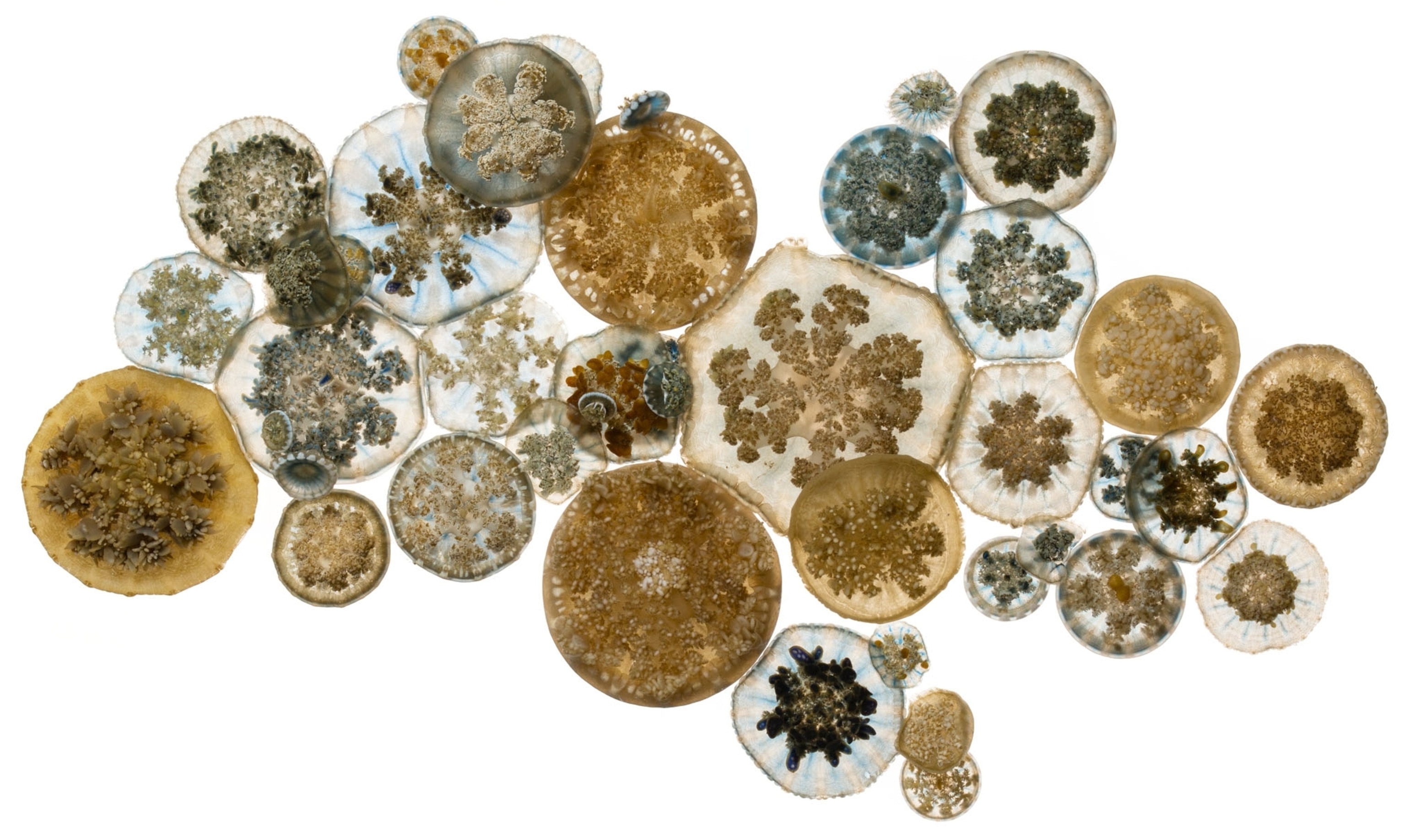

Many of the creatures lumped together as jellyfish are no more closely related than, say, horseflies are to horses. Not only do they occupy disparate branches of the animal family tree, but they also live in different habitats; some like the ocean surface, others the depths, and a few prefer freshwater. What unites them is that they’ve converged on a similarly successful strategy for floating through life: Their bodies are gelatinous.

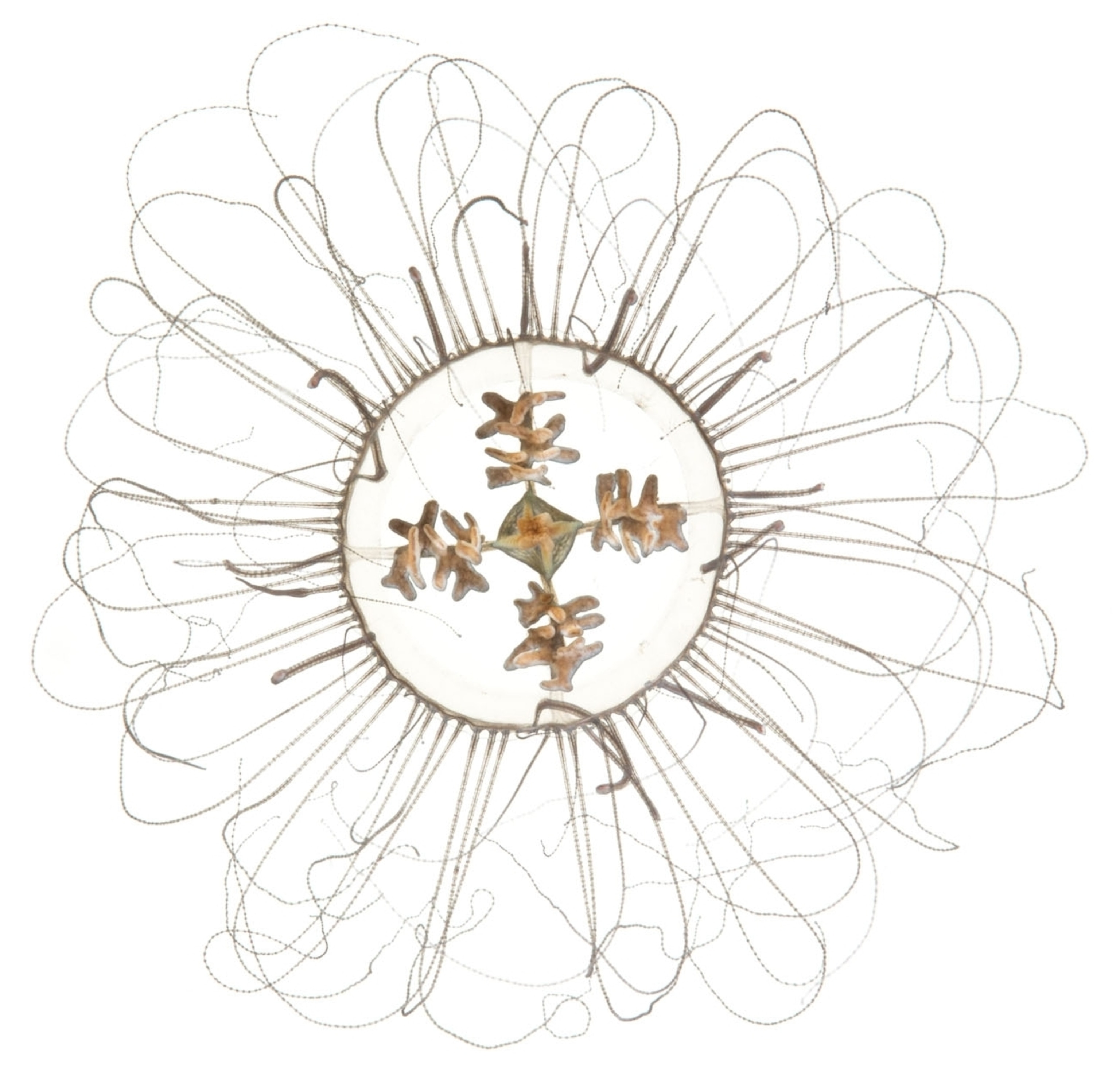

Not surprisingly, given their diverse evolutionary history, jellies exhibit a fantastic range of shapes, sizes, and behaviors. When it comes to reproduction, they’re some of the most versatile creatures on the planet. Jellyfish can produce offspring both sexually and asexually; depending on the species, they may be able to create copies of themselves by dividing in two, or laying down little pods of cells, or spinning off tiny snowflake-shaped clones in a process known as strobilation. Most astonishing of all, some jellies seem able to reproduce from beyond the grave.

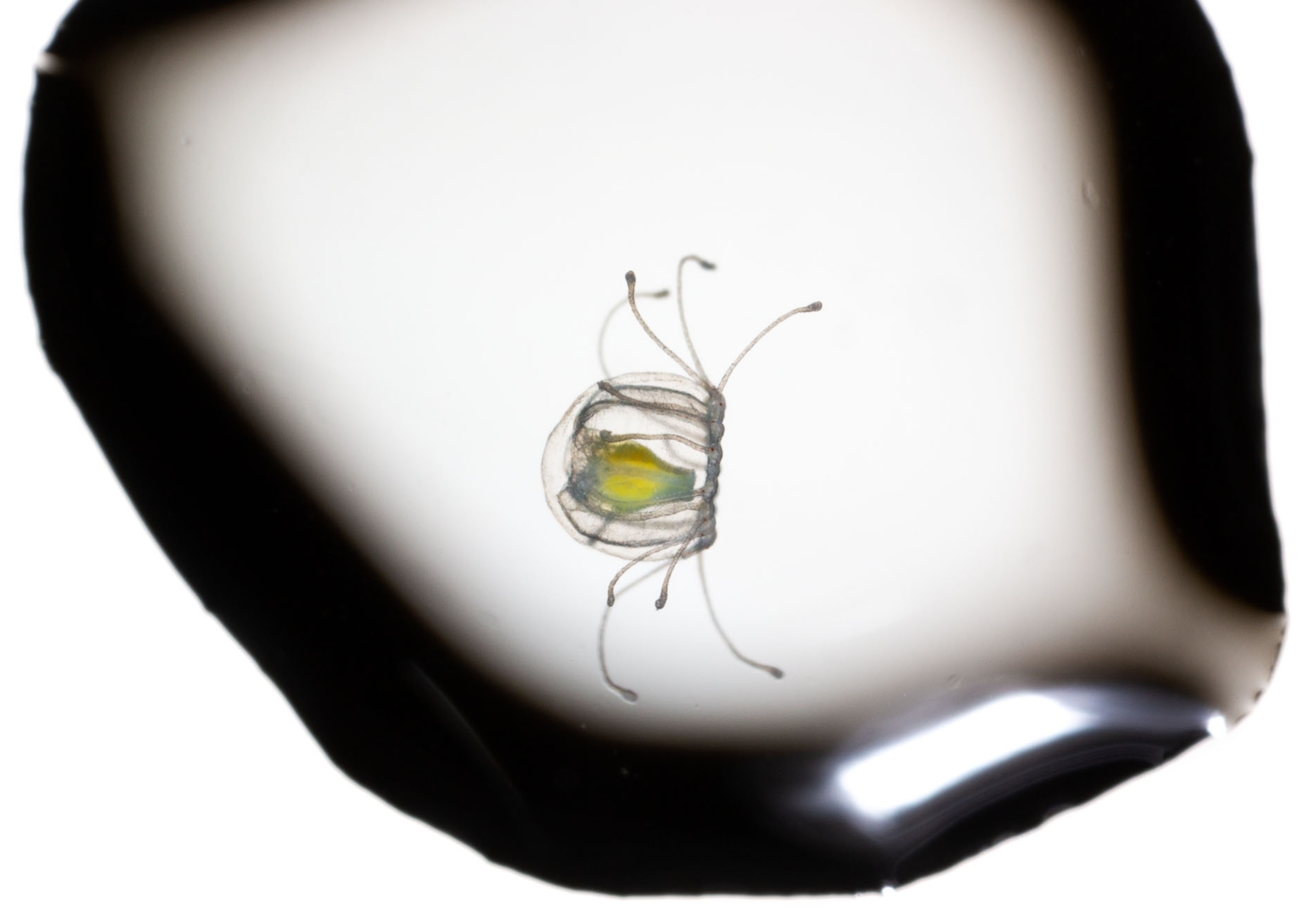

The so-called immortal jellyfish resembles a tiny, hairy thimble and lives in the Mediterranean Sea and also off Japan. Members of the species can reverse the aging process so that instead of expiring, they reconstitute themselves as juveniles. The juvenile then starts the jellyfish’s life cycle all over again. It’s as if a frog, say, were to revert to a tadpole or a butterfly to a caterpillar. Scientists call the near-miraculous process transdifferentiation.

Moon jellies and their cousins, which include lion’s mane jellies and sea nettles, are known as true jellies. They belong to the class Scyphozoa, in the phylum Cnidaria, which also includes corals. (A phylum is such a broad taxonomic category that humans, fish, snakes, frogs, and all other animals with a backbone belong to the same one—the chordates—as do salps, which are sometimes lumped with jellies.) As adults, true jellies are shaped like upside-down saucers or billowing parachutes. They propel themselves through the water by contracting the muscles of their bells, and their tentacles are equipped with stinging cells that shoot out tiny barbed tubes to harpoon floating prey. To reel it into their mouths, they use streamer-like appendages known as oral arms. In some species the oral arms have mouths of their own.

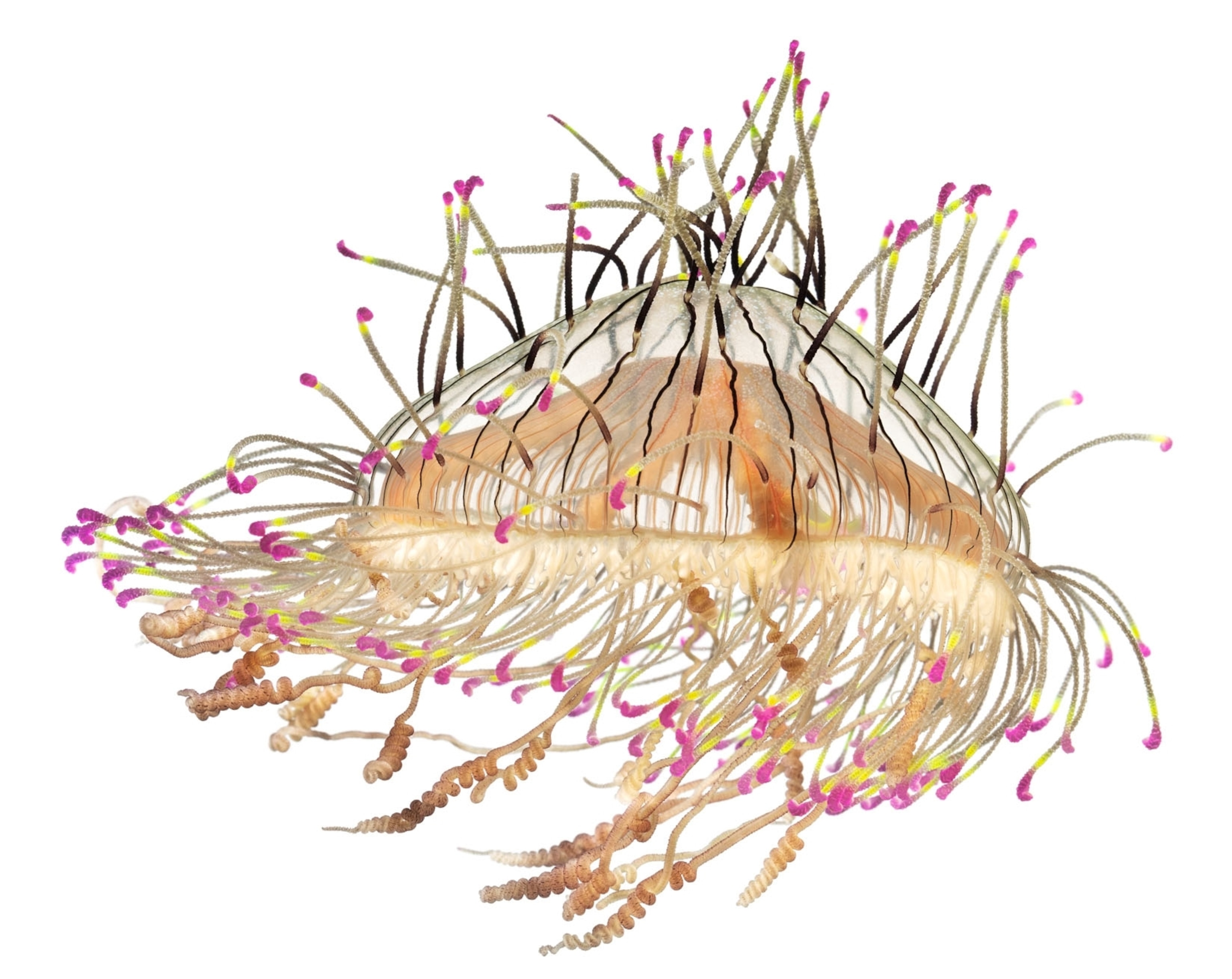

Jellyfish like the dreaded Portuguese man-of-war are also related to corals, but they’re part of a different subgroup, the siphonophores, which practice an unusual form of collective living. What looks like a single man-of-war is technically a colony that developed from the same embryo. Instead of simply growing larger, the embryo sprouts new “bodies,” which take on different functions. Some develop into tentacles, for example; others become reproductive organs.

“In the human life cycle, our body, when we’re born, has all the pieces that are going to be there as an adult,” observes Casey Dunn, a professor of evolutionary biology at Yale University. “The really cool thing about siphonophores is they’ve gone about things in a very different way.”

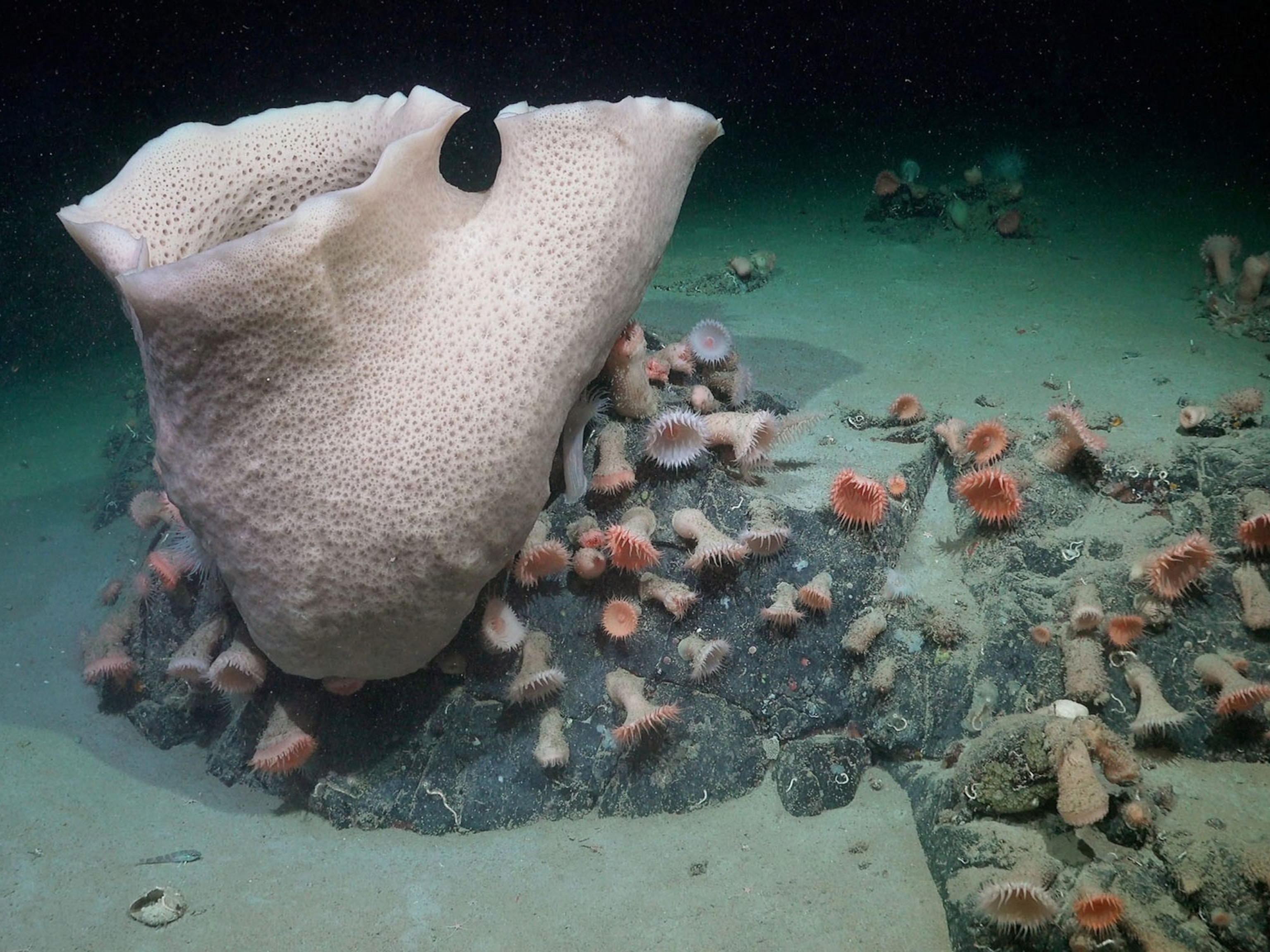

Then there are the ctenophores (pronounced TEH-nuh-fores), which are such oddballs they’ve been placed in a phylum of their own. Also known as comb jellies, for the comblike rows of tiny paddles they use to swim, they tend to be small, delicate, and hard to study. They come in an array of weird body types: Some are flat and ribbonlike; others look more like pockets or little crowns. Most use an adhesive to nab their prey. “They have what’s like exploding glue packets embedded in their tentacles,” explains Steve Haddock, a senior scientist at the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute.

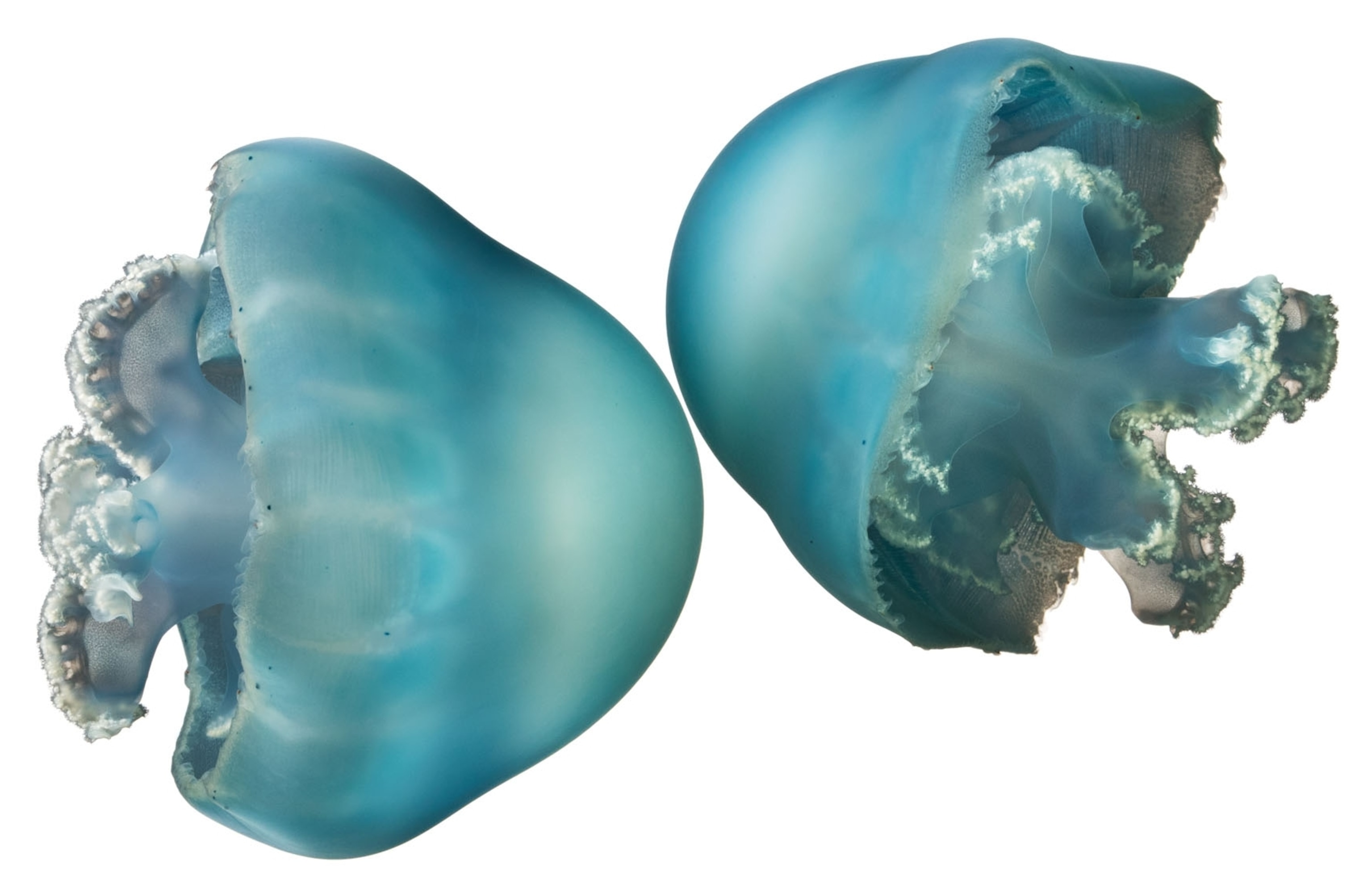

In recent decades jellyfish populations in some parts of the world have boomed. In the 1980s a comb jelly that’s known formally as Mnemiopsis leidyi and informally as the sea walnut showed up in the Black Sea. A native of the western Atlantic, it presumably had been transported in a ship’s ballast water and then been discharged. In the Black Sea it reproduced so prolifically that by 1989 it had reached densities of up to 11 per cubic foot of water. Fish couldn’t compete with the jellies for food—sea walnuts eat as much as 10 times their body weight a day—and many fish became food for the jellies. Local fisheries collapsed.

In other parts of the world, swarms of jellyfish have menaced swimmers and clogged fishing nets. In 2006, beaches in Italy and Spain were closed because of a bloom of jellyfish known as mauve stingers. In 2013 a Swedish nuclear plant temporarily shut down because moon jellies were blocking its intake pipes.

Situations like these led to a spate of reports that jellyfish were taking over the seas. One website warned of the “attack of the blob.” Another predicted “goomageddon.”

But scientists say the situation is more complicated than such headlines suggest. Jellyfish populations fluctuate naturally, and people tend to notice only the boom part of the cycle.

“A big jellyfish bloom makes the headlines, while a lack of a jellyfish bloom isn’t even worth reporting,” says Lucas Brotz, a marine zoologist at the University of British Columbia. While some jellyfish species seem to thrive on human disturbance—off the coast of Namibia, for example, overfishing may have tipped the ecosystem into a new state dominated by compass and crystal jellyfish—other more finicky species appear to be declining. Researchers in a couple parts of the world have reported a drop in the number of jellyfish species they are encountering.

Meanwhile, if people are having more unpleasant encounters with jellyfish, is it because they’re taking over the seas or because we are?

“Anytime we have an adverse encounter with jellyfish, it’s because humans have invaded the oceans,” Haddock says. “We’re the ones who are encroaching into their habitat.” Jellyfish are only doing what they’ve been doing generation after generation for hundreds of millions of years—just pulsing along, silently, brainlessly, and, seen in the right light, gorgeously.