Egypt in the Moment

In the wake of the Arab Spring, the country is full of unprecedented hope—and gnawing fear.

“Thieves and thugs” is our taxi driver’s description of the people we will meet on the third-class train from Aswan to Luxor. This seems to be a common view in the Egyptian countryside after the revolution: Watch out for your safety and avoid the riffraff. At the train station a scowling police officer manning the gate won’t let me pass. “No foreigners are allowed on third class,” he barks. “Forbidden!”

I’m traveling in the fall of 2011 with an Egyptian colleague, Khaled Nagy, who has spent more than 200 days and nights chronicling the rebellion in Cairo. We’re on our way from Abu Simbel in the distant south of Egypt to the Mediterranean city of Alexandria in the north, with many stops along the way. The idea is to travel far from the epicenter of the revolution, Tahrir Square, to see how the changes are playing out in the rest of Egypt.

After much argument and a four-hour delay, we eventually make our way aboard a train. We quickly pay the ticket collector 21 Egyptian pounds, or about three and a half dollars, for two fares to Luxor, more than three hours away.

In our car several of the windows are cracked or broken; many are jammed open to let outside air whip through. This is necessary because there is no air-conditioning in the still-hot days of autumn and also because an acrid smell from the toilets permeates the cars when the air inside is stagnant. A flap to an electrical panel swings open and shut against the wall, and the glass case to the fire extinguisher is smashed in. The extinguisher seems intact.

Some passengers sit motionless, their weary eyes fixed on some invisible point outside the train. A few chat on cell phones. A gap-toothed woman, clad in a black dress common to peasants, carries a cardboard box with three chickens in it. Occasionally one of the birds escapes, flapping its wings and clucking madly.

Men and boys walk up and down the aisles selling tissues, watches, wallets, sewing kits, polyester blankets, cold water in reused plastic bottles, pumpkin seeds, nuts, bread, boiled beans, religious pamphlets, and tea that is poured from giant tin kettles. I get my dusty shoes shined for 50 cents, including a generous tip. A handicapped man slides along the floor on his buttocks, holding up a hand for donations. Across the aisle, a man in a turban points to the view of the palm-fringed Nile from the window and asks, “Do you have a river as beautiful as this?”

As the train rattles along, our fellow travelers gradually warm to us. The passengers we meet, including a muezzin who makes the calls to prayer at a mosque near Luxor and a young man doing his military service in Aswan, seem apprehensive about the revolution. The events of Tahrir are far from their lives. “In the end isn’t life simply about being safe?” says the muezzin, who is traveling with his wife and two young children. He complains about the lack of financial security people feel and about a declining economy. He gets a government salary every month, but others live job to job, some earning as little as ten pounds a day, or less than two dollars. The muezzin may be better off than many, but his wife looks miserable. She spends most of the trip staring blankly out the window, holding a tissue over her nose.

“There is no trust, no security,” says Momen Hassan, the 22-year-old conscript. When I ask his opinion of the revolutionaries in Tahrir, he says, “I’m not against them, but I’m definitely not for them.” He’s not surprised by the misdeeds of the former regime, but he likens corruption to a tree with deep roots: Cut it down, and over time it will grow back. “Democracy is good,” he says, “but we can’t rush it. If you let the leash go completely loose, people will do whatever they want. We need a firm hand.”

This view is not uncommon in the countryside. Nearly everywhere we go, Egyptians express anxiety about al amn—security. Many seem almost paranoid about growing thievery, which was nearly unheard of in Egypt before the revolution, and a potential breakdown in order. A taxi driver in Luxor has bought a Beretta pistol to keep under his seat. Some Egyptians speak darkly of smugglers bringing guns across the border from Libya.

In the Shadow of the Pharaohs

The anxiety and tension alone may be enough to drag the country down. Tourism is a major contributor to Egypt’s economy, yet the tourist sites we visit are all but deserted. At the temple of Ramses the Great at Abu Simbel, souvenir kiosks at the entrance are shuttered, and metal turnstiles are still. Watchmen dressed in galabias look out over Lake Nasser, waiting for fish or crocodiles to poke ripples in the placid surface of the water.

Inside the temple itself there are no jostling tourists. No scents of European perfume, no complaints about the heat or the hassles of travel to flyblown corners of the globe. No tour guides explaining why Ramses II is slaughtering the Hittites in one ancient wall relief or stabbing and stomping Libyan enemies in another. During normal times up to 3,000 foreign tourists would visit this site on a busy day. They’d file through the hall, flanked by eight massive statues of the pharaoh, to reach the inner sanctuary, the holy of holies, where rays of sunlight penetrate precisely twice a year. But eight months after the Egyptian revolution ousted President Hosni Mubarak from power, the number of visitors has plunged to about 150 a day. At four on a Saturday afternoon no other foreigner is in the complex. No one else at all is inside the temple. A solitary swallow flits among the columns.

Just outside, in the shadow of four colossal statues of Ramses, Ahmed Saleh invites me to sit on a wall and have a glass of hot tea. Saleh is an Egyptologist and the general director of Abu Simbel and other monuments in the region of Nubia, in the far south of the country near the Sudanese border. “This is the problem after the revolution,” Saleh tells me. Much is unsettled, and “tourists are afraid that if they come here, they might be attacked.” I mention to Saleh that many Egyptians regard the economic troubles they’re experiencing now as a necessary passage. They see Mubarak as the “last pharaoh” and believe that a new era has arrived—a break with more than 5,000 years of history.

Saleh offers a coy smile. “Both Ramses and Mubarak knew how to use propaganda,” he says. “Both were military men, and both formed family dynasties.” But Saleh is unsure that Mubarak, who was grooming one of his sons to replace him before the revolution, will be the last strongman of Egypt. Pharaohs have been toppled before: Even in ancient times, he says, the aged Pepi II was overthrown in a popular revolt, but dynastic rule returned. “The political life in Egypt has not changed enough to say Mubarak will be the last pharaoh. We’re on the edge of democracy, but we’re still not there.”

Saleh gives many reasons for pessimism: Remnants of the old regime and ruling party remain at many levels of federal and local power. Illiteracy rates are high in Egypt (roughly 40 percent among adults 25 to 65). Many Egyptians see the revolution only as an opportunity to grab what they want or to make wage and contract demands. Unlike Eastern European countries that broke free of communism, Egypt is not part of a wider region with a history of democratic practice. “Arabs won’t easily accept democracy,” Saleh says, “partly because it is against the rule of the father in his family or the chief in his tribe. If a father says, ‘Don’t play,’ you don’t play. He is a dictator. How can you change the mentality of the Egyptian in such a short time?”

Such talk of a static mentality seems cynical at best. Yet it’s a recurrent theme, at least in the Egypt that exists beyond Tahrir. It’s an argument made by those, like Saleh, who support the ideals of the revolution but remain cautious and also by those who want to justify autocratic rule. Taken together, the doubts raise many questions: How strong and deep is Egypt’s revolutionary spirit? Are we seeing one revolution with shared goals or many competing revolutions? Is it possible that Egypt will revert to strongman rule—initially less corrupt than Mubarak’s final years and with some superficial freedoms, but fundamentally the same?

An Islamist Vision

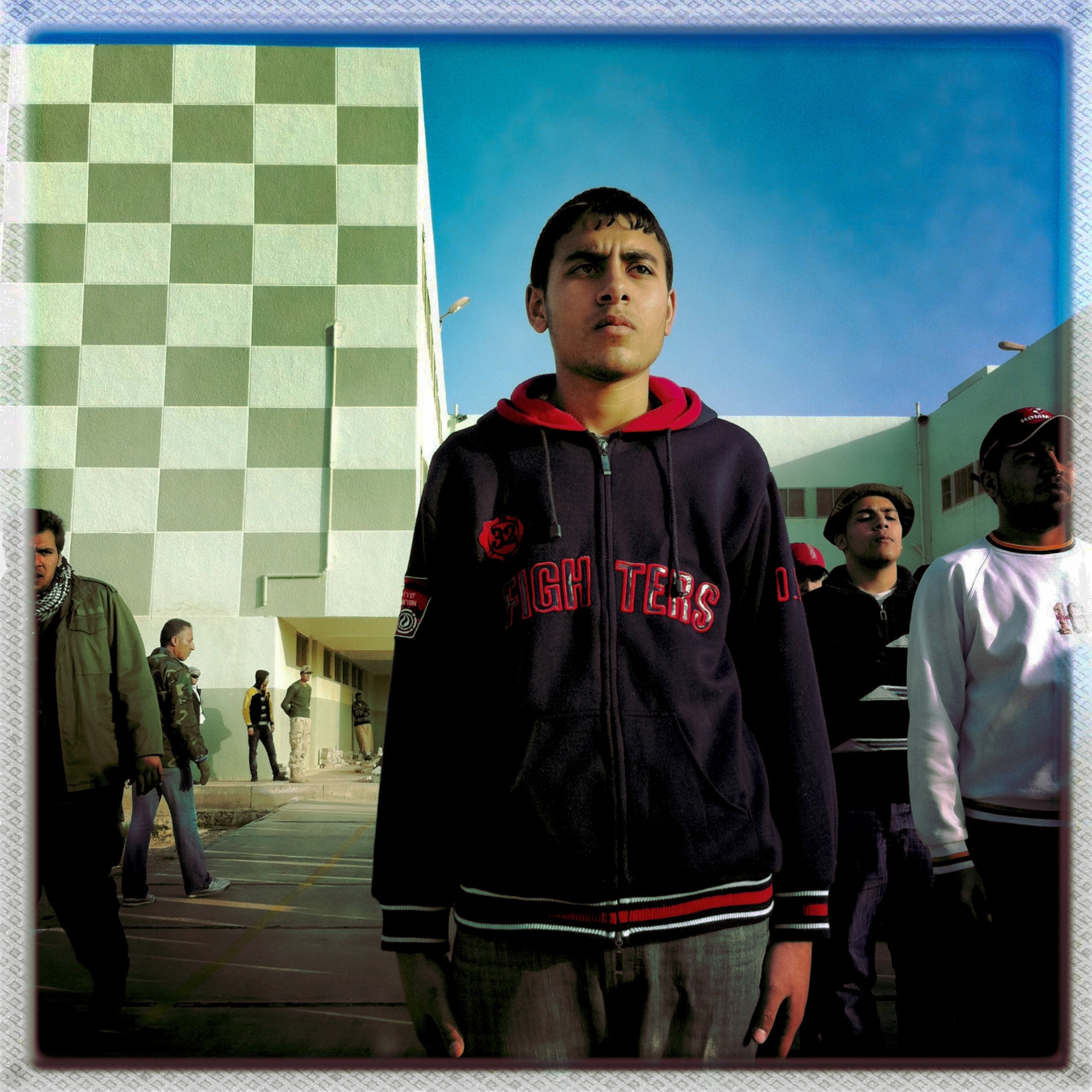

Mohammed Nasser, a young man I met in Tahrir at the height of the protests, in February 2011, is a Salafist, one of those who see the early generations of the Prophet Muhammad’s followers, thesalaf (forefathers), as representing a golden era that should be emulated. (The Salafists did surprisingly well in Egypt’s 2011-12 parliamentary elections, winning nearly 25 percent of the seats.) Nasser has a long, wispy beard, a shaved upper lip in the manner common among the Salafists, and gentle eyes. When I first met him, he was an unemployed university graduate with a wife and newborn child. He had traveled to Cairo without enough money for the return fare and subsisted there for many days largely on bread and dates.

When I call him on his cell phone months later, Nasser says I’m welcome to visit him at his home in the Nile Delta near Zagazig. Khaled and I arrive bearing bags of fresh fruit, and at first Nasser wants me to put them back in the car, saying he can’t accept such a gift. He relents, then invites us into the sitting room of his small apartment. Nasser’s wife, who in public wears the billowing black dress and full veil called the niqab, never appears from the kitchen. She doesn’t see men in her home who are not part of her family, and when she has female guests over, the men in the apartment must retreat to other places. We are joined by Nasser’s brother-in-law, a bearded English teacher named Abdel Halim Gamal Eddin.

Nasser asks if I’d be more comfortable eating from the coffee table or seated on the carpeted floor, which is customary. I opt for the floor. The food is placed between us: tender beef, which we pull from the bone with our fingers, as well as rice, soup, and fatta, an Egyptian casserole of toasted bread and vegetables cooked in meat stock. When Nasser thinks I am not taking enough meat, he hands me a chunk and insists I take more.

I ask whether the revolution has yet had any impact, good or bad, on Nasser’s circumstances. Despite a university degree, Nasser has never landed a salaried job. He earns about 500 pounds ($83) a month laying floor tile. Like so many other Egyptians, he is part of the country’s vast informal economy, employed day to day, depending on the availability of work. But he didn’t participate in Tahrir because he was frustrated by his financial prospects, he says. “It wasn’t a revolution of the poor. It was a revolution against injustice.”

Even though Egyptians bemoan the relative erosion of public safety after the revolution, few seem wistful about the lower profile of the dreaded state security forces. These are the police who spied on everyone and ran torture cells. Mubarak’s regime justified brutal state security as a necessary measure to keep tabs on his enemies, primarily Islamists. After watching militants gun down his predecessor, Anwar Sadat, at a military parade, Mubarak feared the Islamists would try to take power if he didn’t keep a firm hand.

Gamal Eddin, 35, tells us he spent four years in prison under Mubarak, apparently because he had been preaching that it is the duty of Muslims to liberate Al Aqsa Mosque in Jerusalem. He seems well respected by the others in the room, perhaps because he is a teacher and perhaps because his prison time gives him status. He smiles often and has a friendly demeanor, even when telling the story of his incarceration. The security forces first grabbed his father-in-law, holding him hostage until Gamal Eddin turned himself in. Then he was sent to an underground dungeon in Cairo, where he was blindfolded and shackled for 38 days. The handcuffs were stamped Made in USA, he says. Then he was sent to another prison, and then another, where he was held until 2010. He was never charged.

Now he wants a president who is “both firm and kind,” someone who would apply strict Islamic rule “gradually, so it wins the acceptance of the people.” When I mention that one of the Egyptians who plans to run for president is a woman, Nasser and Gamal Eddin shake their heads. Both insist that Islam doesn’t allow for that. And the president can’t be a Christian either: That would lead to “a lot of troubles” in a Muslim-majority land, they say.

Security forces have just suppressed a Christian protest in Cairo; some two dozen people were killed. Gamal Eddin is quick to note that their village has a “big church” and says, “We don’t have an idea to discriminate.” When I ask if pharaonic tombs and temples should be destroyed, as some radical Islamists have argued, the two men say they would defer to higher religious authorities. When I press, Gamal Eddin says that Amr ibn al-As, the Muslim military commander who led the conquest of Egypt in the seventh century, didn’t harm the monuments, and that seems like a good precedent. “The revolution isn’t finished,” says Nasser. But he sees progress. “Before, there was no dialogue about the future. Now there is one.”

My colleague Khaled, an adventuresome sort who enjoys music, the company of women, and an occasional glass of wine, admires these two Islamists. He remarks on Gamal Eddin’s good-natured optimism despite all he has been through. Egyptians identify with Islamic fundamentalists because they’ve been “oppressed so long,” Khaled says, and also because Egyptians tend to be socially conservative. Many ordinary Egyptians object to the social permissiveness of liberals in the forefront of the revolution. They worry, Khaled tells me, that political changes could make Egypt like “Paris, make us all like Americans.”

A Mecca of Modernity

For most of our trip Khaled and I aren’t more than a few miles from the Nile, in a verdant valley bordered by desert. Without the river, the country would be a wasteland. Only about 5 percent of Egypt is inhabitable. Beyond the valley lies an inhospitable, sunbaked realm that ancient Egyptians called the “red land.”

The towns and villages along the Nile can feel constricted, even claustrophobic. Arriving in Alexandria, breathing the sea air blowing across the corniche from the Mediterranean, is liberating. The city has long been Egypt’s gateway to the world. From ancient times it was a cosmopolitan center where many languages were spoken and ideas exchanged. Historian Mostafa El-Abbadi, 83, recalls a city that once boasted 16 daily papers in different languages, including Greek, Italian, English, and Armenian.

The more cosmopolitan aspects of the city began to die out during the era of Gamal Abdel Nasser, who moved to concentrate power more firmly in Cairo. Now Alexandria is overcrowded and impoverished. But some leading Egyptians aim to restore its lost glory.

No place better embodies that effort than the Library of Alexandria, a gleaming, modern facility that opened in 2002 a short distance from the site of its Ptolemaic predecessor, the most significant library of ancient times. Visitors enter the main building through large glass doors, then pass through a metal detector. We see people of many backgrounds and ideologies, including women in black niqabs and men in the white galabias and long beards that often signify hard-line fundamentalist beliefs. A woman wearing a hijab, the type of veil that covers the hair and leaves the face exposed, is doing research on Shakespeare, and a young Egyptian man in a flaming pink T-shirt has come to download games and movies, including an action film, The Fast and the Furious.

As visitors collect their backpacks and metal objects from the scanner, they stand under a towering abstract sculpture of a nude woman. The sculpture, called “Hypatia,” has been cut from slabs of steel and shows the outline of a graceful woman with full breasts. It is named after a female mathematician, astronomer, and philosopher of ancient Alexandria. A placard on the statue notes that Hypatia was murdered by people “who considered her one of the defenders of paganism and the Classic era, but she was actually a victim of fanatic ideologists.”

In a way, the Alexandria library is more revolutionary than anything that has happened in Tahrir. The facility includes a library for the blind, two children’s libraries, a maps library, conference halls, academic research centers, an archaeological museum, art exhibits, a planetarium, Internet-linked computers and Wi-Fi access, 1.24 million books and capacity for six million more. It hosts theater productions and concerts. It has a supercomputer that can make trillions of calculations per second. It has digital archives of Egyptian history and 43 racks of computers that aim to collect every accessible page that has ever appeared on the Internet. Its collections contain books that have been banned elsewhere in the Middle East. Indeed, it is an oasis of free thought in a region where people are, more often than not, told what to think, and then told to memorize it and not to entertain other ideas.

The first and only library director until now, Ismail Serageldin, told the Mubarak regime he wouldn’t take the post unless the library could take care of its own security, without the involvement of the Amn al Dawla, or state security police. “That policy allowed us to have lots of activities. The Amn al Dawla couldn’t come to the Library of Alexandria and give us orders,” says Khaled Azab, director of the special projects department. “You can think and talk about anything inside the Library of Alexandria.”

Most of the 2,700 employees are aged 25 to 35, and the younger generation is included in all planning and programs, says Azab. During the protests to topple the regime, young demonstrators formed a cordon around the library to protect it from possible harm.

The Journey Ahead

Abu Simbel, the towns and villages of the Nile Valley, the Nile Delta, and Alexandria: Every stop on our journey showed us something different. In the end we found that the “other Egypt” beyond Tahrir is a kaleidoscope of jumbled aspirations and fears. Turn the kaleidoscope one way, and you see ordinary Egyptians just scraping to get by, worried that their already difficult lives could get worse; turn again, and deeply idealistic Islamists are hoping to turn Egypt into a theocracy; one more turn, and you find secularists aiming to build a multicultural Egypt with minority rights and guaranteed freedoms for all.

Many Egyptians simply seemed to be waiting for clear patterns to emerge—for the colorful bits and pieces of a new Egypt to fall into place. Some worried the country could come undone; others feared that powerful forces in the military and elsewhere were stoking those concerns in an attempt to retain power. A fundamental divide seemed to exist between those whose thoughts were focused mainly on stability and security, and those who were willing to take risks to achieve real democratic change.

On a mechanized farm in the far south of the country I asked an engineer named Mohammed Haggag about the argument that an authoritarian culture exists in Egypt, deeply embedded within families and tribes, and that a strongman will return. He firmly disagreed. “The relationship between me and my children is very different than the relationship between my father and me,” Haggag said. “When my father said, ‘Stop speaking,’ I stopped speaking. I can’t do that with my own children.”

Did this mean that Haggag, 59, thought the revolution would be a success? “It’s as if we have been lost in the desert,” he said, in a tone that suggested a determination to persevere. “We have found our way, but it will still take a long time to get out.”