Oysters are making a comeback on menus and in the water—for now

In the Chesapeake Bay, the once decimated oyster industry is having a renaissance. But the effects of climate change are a looming threat for farmers and oyster lovers.

A 1913 issue of National Geographic called the Chesapeake Bay the “greatest oyster ground in the world,” declaring Baltimore its capital. The bay was once so densely populated by the eastern oyster, Crassostrea virginica, it’s said that the hulls of early European boats sailing up the Chesapeake were scraped by the shells.

Over a century ago, the oyster sparked a harvesting frenzy in the mid-Atlantic. At the local oyster industry’s peak during the late 19th century, more than 20 million bushels of oysters were pulled from the Chesapeake Bay every year. But in the decades that followed, oystermen harvested more quickly than the oyster could reproduce, and they did so with large, scraping tools that transformed craggy reefs into muddy substrates in which oysters couldn’t survive.

By 2005, the National Marine Fisheries Service considered placing the eastern oyster on the endangered species list. Today, oyster populations are still less than one percent of their former numbers.

Now, climate change is adding another threat. Seen both in sudden and subtle changes, climate change is settling into the Chesapeake with fingerprints on the sudden onslaught of torrential rain and slowly changing ocean chemistry.

But the small and mighty bivalve is still making a comeback in the bay, the largest estuary in the United States.

When it comes out of the water, its heart is still beating… It’s dirty. It’s primitive… It’s daring.Patrick Oliver, Director of Farms, Rappahannock Oyster Company

This year, Maryland oyster fishers sold a half million bushels of wild oysters, the most since 1987, and in Virginia around half a million bushels have been consistently harvested annually since 2014, steadily ticking up from their record low in 1996, when just over 17,000 bushels came in. The rise of aquaculture—farmed oysters—has also skyrocketed in the bay.

In 1998, revenue generated by farmed oysters and clams in Virginia totaled around $10 million annually; in 2020 it was valued at over $30 million for oysters alone.

And local environmental groups have an ambitious plan to restore the kinds of reefs that once imperiled ships—not only to support the oyster industry, but also the bay’s health. A single oyster can filter 50 gallons of water every day, removing pollution and improving water quality.

While the Chesapeake’s first oyster boom may have been a victim of human appetites, today’s oyster renaissance is being closely shepherded by human hands.

“In Virginia, our shellfish sector is doing really well, and a lot of that is based on advances in aquaculture,” says Mike Schwarz, an oyster expert at Virginia Tech. “Keeping it growing and being sustainable is part of looking at climate change.”

Highlighting merroir

On a sunny summer afternoon, Patrick Oliver, Rappahannock Oyster Company's director of farms, motors through rows of submerged oyster cages that bob just below the bay’s surface with the gentle current. Inspecting ropes and knots to make sure cages are secure, he muses on why the oyster inspires such devoted fans. “When it comes out of the water, its heart is still beating… It’s dirty. It’s primitive… It’s daring.”

Over the past 20 years, oysters have joined the ranks of wine and cheese as menu items for foodies. Just a few hundred feet from the farm, the Rappahannock’s onshore tasting room is filled with patrons; oyster enthusiasts from throughout the region drive to the remote farm to eat raw oysters paired with glasses of bubbles. They buy oysters by the case, along with Rappahannock branded T-shirts and shucking knives that brandish their oyster loyalties.

One reason for this half-shell renaissance is that farmers market their raw oysters on restaurant menus like wine. Just as wine grapes can carry the terroir of the soils in which they grow, raw oysters have a signature merroir that reflects the water they grew in. Common tasting notes describe oysters as fresh or salty, buttery or sweet.

Oysters are also as trendy now as they were when they were slurped down in early 19th century New York city oyster cellars. Paired with a dirty martini, they were recently deemed by New York Magazine the “hot-girl meal of summer.”

And while the clever marketing has improved demand, genetic meddling helped guarantee supply from oyster farms.

In the wild, oysters spawn during the hot summer months, releasing a snowstorm of sperm and eggs into the water. The energy spent on reproducing makes them thin and watery, which is one reason people are often warned against eating oysters during months without the letter “R,” the second reason the public health risk of eating hot, raw shellfish before the advent of refrigeration and water quality testing.

But in the late 1990's, scientists working at William and Mary’s Virginia Institute of Marine Science (VIMS) introduced a genetic mutant oyster for the bay by breeding one that doesn’t spawn.

In the wild, the Chesapeake’s eastern oyster is a diploid, meaning it has two sets of chromosomes, but by manipulating the breeding process, scientists created a single oyster with three sets—a triploid. Triploids are infertile, created in a lab by crossing a wild female oyster with a farmed male one. They don’t shrink during reproduction and can guarantee a fat year-round supply for farmers to sell, as long as they’re able to buy from growers who specialize in triploid spat, what baby oysters are called when they’re old enough to attach to a substrate. Over 90 percent of farmed Virginia oysters are triploids. One study even showed that triploids in the Chesapeake grew to market size almost a year faster than diploids, were more likely to survive, and yielded more meat.

Globally, aquaculture is a rapidly growing industry. An estimated 95 percent of all oysters consumed comes from farms, and the aquaculture industry is expected to provide two-thirds of the world’s seafood by 2030. Yet many of these farms, raising finned fish or shrimp, expel fecal matter and pollutants used in production—not oysters, which feed themselves and expel clean water.

The bivalves are increasingly being heralded as a food for the future—a sustainable, clean product to invest in as climate change warms world oceans and fish populations decline.

As they grow, oysters use calcium carbonate ions to build their hard shells. Inside, the gray flesh contains their heart, mouth, intestines, stomach, and gills. When the oyster senses water conditions are good, it relaxes a tiny adductor muscle, opening slightly. In flows sea water, passing over the gills, which trap and feed on algae and bacteria. During this process, oysters also feed on pollution, like nitrogen running into the bay from fertilizer used on farms upstream. Pulling it inside their mantle, it’s then stored in their flesh and shell, and clean water is expelled.

As Oliver walks down a dock with concrete oyster tanks attached to its side, he points to two tanks—one with six-month-old oysters and one without.

“It just takes a day for these tanks to turn crystal clear,” he says. Indeed, the tank with oysters is strikingly clean, like spring water, a contrast to the cloudy, oyster-less tank next to it.

The environmental potential has attracted new farmers—even as the number of all types of farmers declines nationwide—who see marketing potential in the bivalve.

“I do think they’re the unsung heroes of the environmental movement,” says Sarah Matheson Harris of oysters. She’s a former advertising associate turned oyster farmer who says she couldn’t imagine starting a business that lacked “an environmental backbone.”

With her husband and brother-in-law, she runs the Matheson Oyster Company, a five-year-old company in Guinea, Virginia, an hour south of Rappahannock. And at her farm, set in a marshy inlet surrounded by tall grass and bald cypress trees, she sees proof of oysters’ environmental potential.

“We see really thriving ecosystems around our cages because smaller bait fish are attracted to the algae and then bigger fish will come,” Matheson says. “They’re like the coral reef of this area.”

The plan to restore great oyster reefs

Globally, 85 percent of all oyster reefs have been lost, and some of the world’s last remaining wild oyster fisheries are along the East and Gulf Coasts.

When at their historic populations, the Chesapeake’s oysters could clean the entire bay—19 trillion gallons—in just a matter of days. Today’s population would need a year to filter clean the same volume of water. But that’s slowly changing as environmentalists work to bring back not just the oyster, but the reefs they once formed.

In the wild, floating oyster larvae settle on piles of old oysters, layering new shell on old to form towers of oyster clumps that spread out for miles. As these habitats form, they attract other shellfish like mussels, barnacles, and sea anemones that provide nurseries for fish and shrimp. Bringing back oyster reefs revives an entire ecosystem.

“This is an expensive endeavor,” says Allison Colden, a fisheries scientist with the Chesapeake Bay Foundation (CBF). “We are working to bring back a species challenged by lack of habitat, lack of adults for reproduction—it requires a lot of work.”

One challenge has been restoring a three-dimensional hard surface for baby oysters to settle on. Oysters simply dropped into the water have less access to food-filled water currents, and when rains push river water into the bay, the bivalves can easily be smothered by the incoming sediment. That's why restoration groups are reconstructing reefs with old shell and other material.

In New York, the Billion Oyster Project has replanted 100 living million oysters in New York Harbor since the project began in 2014. To do so, they’ve collected two million shells from local restaurants for substrate.

Environmental groups in Maryland and Virginia collectively plan to restore 10 times the oysters planned for New York, restoring 10 billion by 2025. While they too use spent restaurant half shells, they’ve also constructed artificial reefs from granite and concrete.

Nestled into the marshy tendrils of Maryland’s Eastern Shore, Harris Creek’s restoration—one of the largest ever undertaken in the Chesapeake—was completed in 2021. Two billion oysters have been planted on 350 acres of creek bottom.

“The density of oysters we’re seeing on these reefs have been orders of magnitude higher than expected,” says Colden. “These projects are also capable of removing a tremendous amount of nitrogen and phosphorous. We’re seeing tremendous returns so far in the ecosystem.”

Every year, the Harris Creek reefs remove nitrogen equal to 20,000 bags of fertilizer, estimates the CBF, a service worth about $1.7 million.

Oysters are such successful water cleaners that the state of Maryland is now helping oyster farmers cash in on their water purifying potential. To offset what they discharge into the bay, polluters can buy nutrient credits from oyster farmers, with larger farms offering more credits based on their larger potential to purify water.

“It was a way to start cash flowing and get the equipment out there as the new farming industry was happening,” says Jordan Shockley of Blue Oyster Environmental, a group that brokers nutrient credits between farmers and companies.

And it’s not just water pollution oysters can help clean. Studies have shown that oyster reefs can help absorb excess carbon pollution and that aquaculture provides a low-carbon alternative to other sources of animal protein like chicken, pork, and beef. One study estimated that if 10 percent of U.S. beef consumption were replaced with oysters grown on farms, the reduction in greenhouse gasses would equal nearly 11 million cars taken off the road.

“Shellfish can have such a big impact on climate change if the right approach is taken,” says Shockley. “But on the flip side, climate change can really impact growth and revitalization in a negative way.”

How will a changing climate change the Chesapeake?

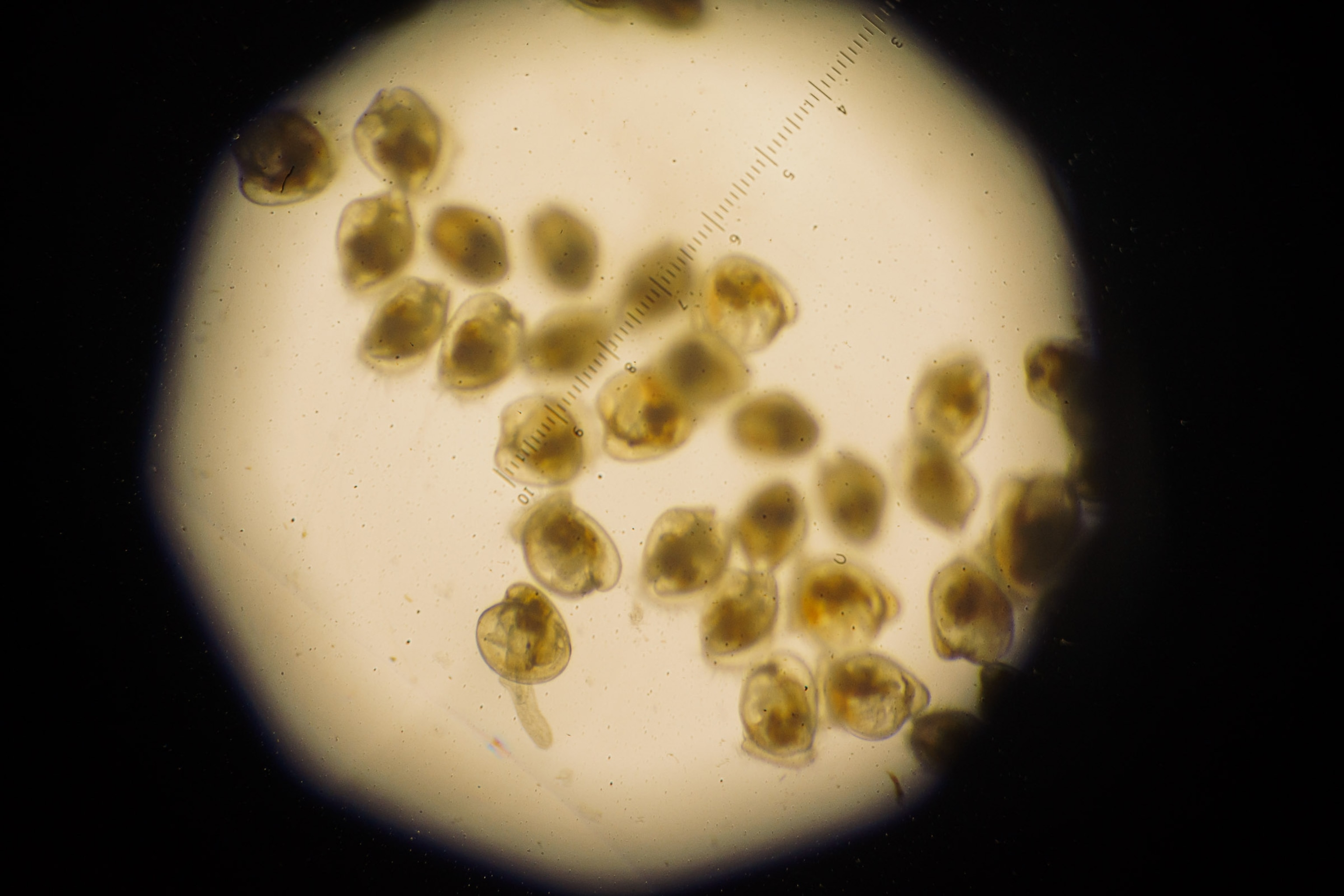

Crunching gravel underfoot, Mike Congrove, who runs Oyster Seed Holdings, LLC, walks to open-air tanks full of water teetering on a shore where the Rappahannock River opens into the bay. He plunges his forearm into one tank’s light brown water and pulls up a clump of four-week-old oysters. Barely bigger than a baby’s fingernail, dozens fit in the center of his hand, the teardrop outline of their shells already distinct.

The hatchery—an operation where oysters are carefully bred, fed, and grown—produces 100 million baby oysters every year. After about six weeks—when the oysters are a sixteenth of an inch—they’re shipped off to farms up and down the East Coast, where they’re placed in wire mesh cages anchored just offshore. They’ll spend two years there growing big enough to reach market size—about three inches—and be sold to restaurants across the country.

At even younger stages, as larvae, baby oysters can be as tiny as 1/150 of an inch and nearly transparent. Without a shell’s hard exterior, they’re especially vulnerable to changes in salinity and pH. That makes Congrove the critical first step for many companies in the oyster supply chain: Without success at the hatchery, oyster farmers have nothing to grow. And to successfully operate a hatchery, nature must comply.

As he walks back to the warehouse, Congrove points out “miles of plumbing” piping bay water directly to the many tubs and tanks inside. In the building it’s balmy, which oysters like, and the loud whir of machinery hums in the background. It looks more science lab than farm, with one wing devoted to growing bright, green algae under fluorescent lights—the oysters’ food.

The bay water flowing in is brackish, a mix of salty and fresh, which oysters need to fight off harmful bacteria and parasites. The wrong mix can impact an oyster’s respiratory and immune systems, making them more susceptible to disease or death. On average, says Congrove, healthy salinity measures about 15 parts per thousands (ppt). When it drops below 10 ppt, and especially if it stays there, oysters can get sick, which is why in the 2018-19 winter, he worried when salinity clocked in at five to six ppt for months. Over half the larvae didn’t make it. “Sales were at 50 percent of normal… I’m not sure we’d be able to manage two [low salinity] years financially,” says Congrove.

One destructive effect of climate change is its influence on rainfall. For every degree Fahrenheit the atmosphere warms, it can hold 7 percent more moisture, which can unleash the kinds of deluges experienced this year from Yellowstone National Park to Pakistan. The northeastern U.S. has seen a 70 percent increase in extreme rainfall since the 1950s. One study analyzing Virginia rainfall trends from 1947 to 2016 found some parts of the state saw rainfall rise by as much as an inch, and it was more likely to fall in quick bursts.

And while the influx of freshwater is a present concern, oyster growers and scientists are carefully monitoring and studying the water to determine when acidity might rise, another problem for oysters.

Oceans absorb about a third of the world’s carbon emissions, setting off a chemical reaction that lowers pH levels and results in “ocean acidification.” More acidic conditions can be deadly for animals like oysters because it reduces the availability of the calcium molecules they use to build their shells.

An early warning sign that oysters could be decimated by ocean acidification came more than a decade ago, in the Pacific Northwest. Between 2005 and 2009, billions of baby oysters were mysteriously dying. One Oregon hatchery reported seeing oyster larvae dissolve in their tanks.

Last year, VIMS began a $1.1 million research project to study how ocean acidification will impact oysters and other shellfish growing in the Chesapeake by the year 2050. The bay has already experienced pockets of acidification caused by polluted runoff, which spurs enormous algal blooms that result in acidic waters. Scientists worry this localized pollution will compound the threat from acidification caused by climate change.

Research is still ongoing, but trends pointing to a more acidic future are already emerging in preliminary data.

“[Ocean acidification] has been significant in the past, but as temperatures increase, we’re expecting what we’ve seen already to be more dramatic,” says Marjy Friedrichs, a climate scientist at VIMS.

For scientists trying to restore the bay to its former glory, climate change means the small rebirth the oyster population has seen thus far needs to become a full-scale revival—fast.

“Climate change impacts are going to make restoration harder. From my perspective we need to do absolutely as much as we can now in order to restore their habitat because it will only get harder,” says Colden. “There are some areas in the upper part of the bay where there were once really robust populations historically that now cannot support oysters.”

Oysters chart a course for the future

In a dimly lit corner at the back of Congrove’s hatchery, a cluster of tanks form the alcove he calls the research and development department. Working with VIMS and Virginia Tech, he’s testing out a system that would recirculate treated seawater throughout the hatchery, rather than relying on water straight from the bay that might hurt the oysters.

The system is only three years old, but Virginia scientists hope it will provide a blueprint for other oyster hatcheries facing a similarly uncertain climate future. In Washington State and Maine, farmers have invested millions in similar technological workarounds.

“I’m always amazed at the resiliency of the industry. You have some folks that have to fold and that’s understandable, but so many hang in there and just make it work,” says Karen Hudson, science advisor at VIMS who works as the go-between for researchers and farmers. “The industry is not done growing yet.”

The parking lot of the Rappahannock Oyster Company is nearly full when Oliver docks his boat, securing rope around a barnacle-encrusted piling. He’s proud of what he does (“just keeping these things alive”) and that he can grow something people love and that benefits the environment he grew up in.

“People my age didn’t have a chance to eat oysters. There was this period where you just didn’t have them,” says Oliver. “Now it’s the younger generation’s chance to dive into that world.”