What Will Make Us Care Enough to Save Endangered Species?

A photographer and a scientist hope that evocative photos will ignite a passion for protecting threatened animals.

Consider the shoebill, whose photo opens this article. It’s a one-of-a-kind species on the verge of extinction—exactly the type targeted for protection by the Evolutionarily Distinct and Globally Endangered species program, aka EDGE of Existence. But when I started the EDGE initiative in 2007, the challenge was getting people who’d never heard of those animals to commit to protecting them.

Ideally I could have gone to the leading marketing agency for nature and asked what to do to get people to emotionally connect with these weird and wonderful creatures. But no such agency exists—and we’ve only begun to develop both the art and science of making this vital connection.

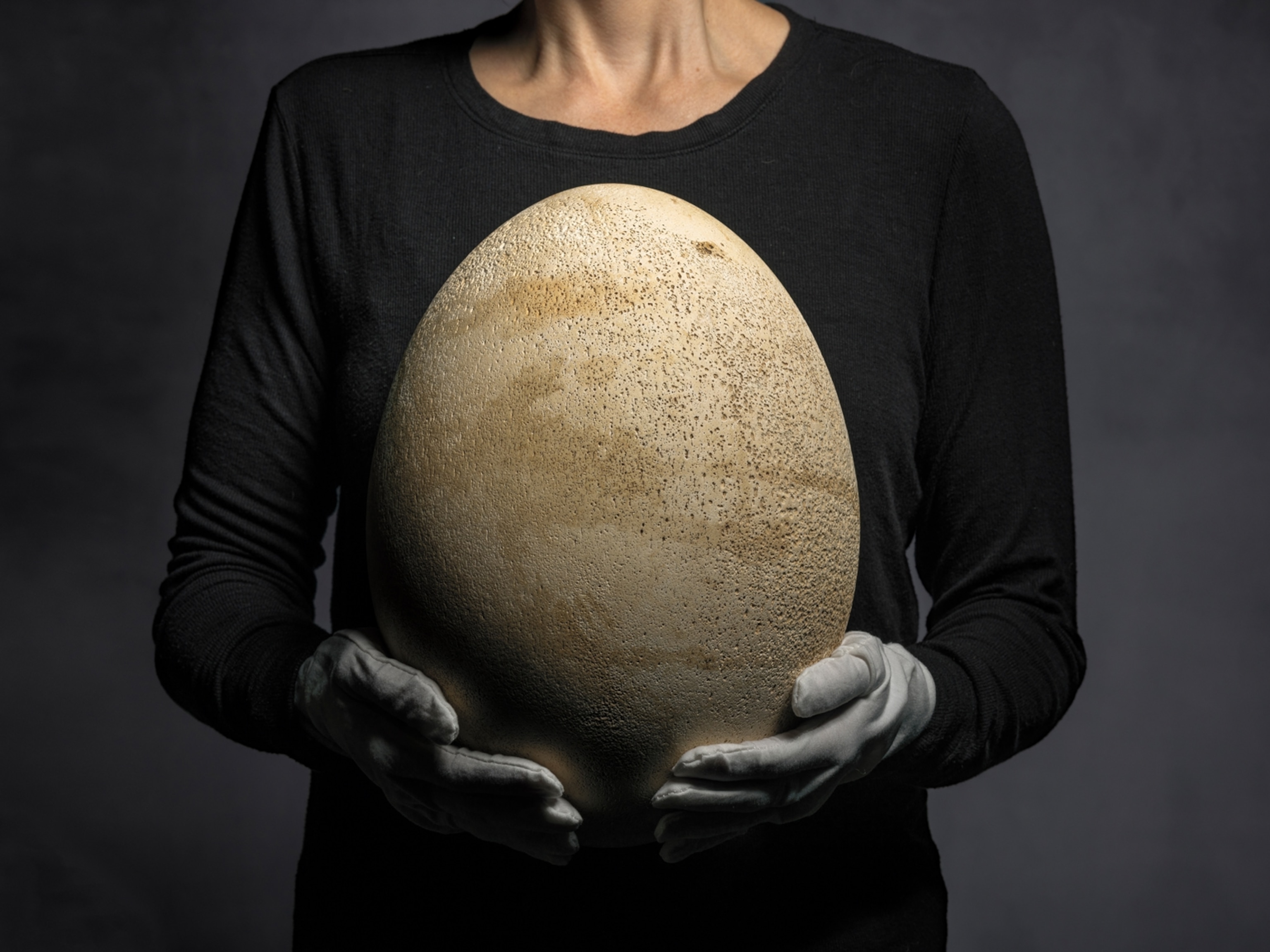

Tim Flach photographed the birds in this article; all are in his book Endangered, to which I contributed. Flach has a unique ability to capture an animal’s essence and an affinity for unusual, obscure creatures. We saw the book as a great opportunity to explore which images of species and habitats would elicit an emotional response.

Were people connecting to species that were larger? More colorful? Or that had traits similar to human babies’, such as big eyes? Was it more powerful if species were pictured in portrait style or in their native habitat? Did the viewer connect through seemingly shared emotions or behaviors, such as maternal gestures, fear, and vulnerability?

Flach’s images have helped start the discussion. Now we at National Geographic, through our Making the Case for Nature grants program, are inviting experts to offer ideas about how to better connect humans with the natural world. It’s a critical question; our future depends on it.

THE YEAR OF THE BIRD

National Geographic is partnering with the National Audubon Society, BirdLife International, and the Cornell Lab of Ornithology to celebrate the centennial of the Migratory Bird Treaty Act. Watch for more stories, books, and events throughout the year.