See what’s new about these dogs, plants, and ancient fossils

Scientists uncovered the dogs’ screening skills, the plants’ gift for camouflage, and the true identity of an amphibian beautifully preserved in amber.

Sniffing out the deadly virus

Scientists are training working dogs to detect COVID-19–related compounds in human sweat. Sniffers such as Floki, an English springer spaniel at Australia’s University of Adelaide, could be deployed to airports, hospitals, and other facilities worldwide to help screen for the virus. —Hicks Wogan

Evolving to Evade Harvest

For centuries in China’s Hengduan Mountains, herbalists have collected Fritillaria delavayi plant bulbs for use in traditional medicine. A recent study found some F. delavayi have changed color from light green to gray or brown to match their rocky habitat—a camouflaging more common in heavily picked areas. It seems this clever plant is evolving to be less visible to its primary predator: humans. —HW

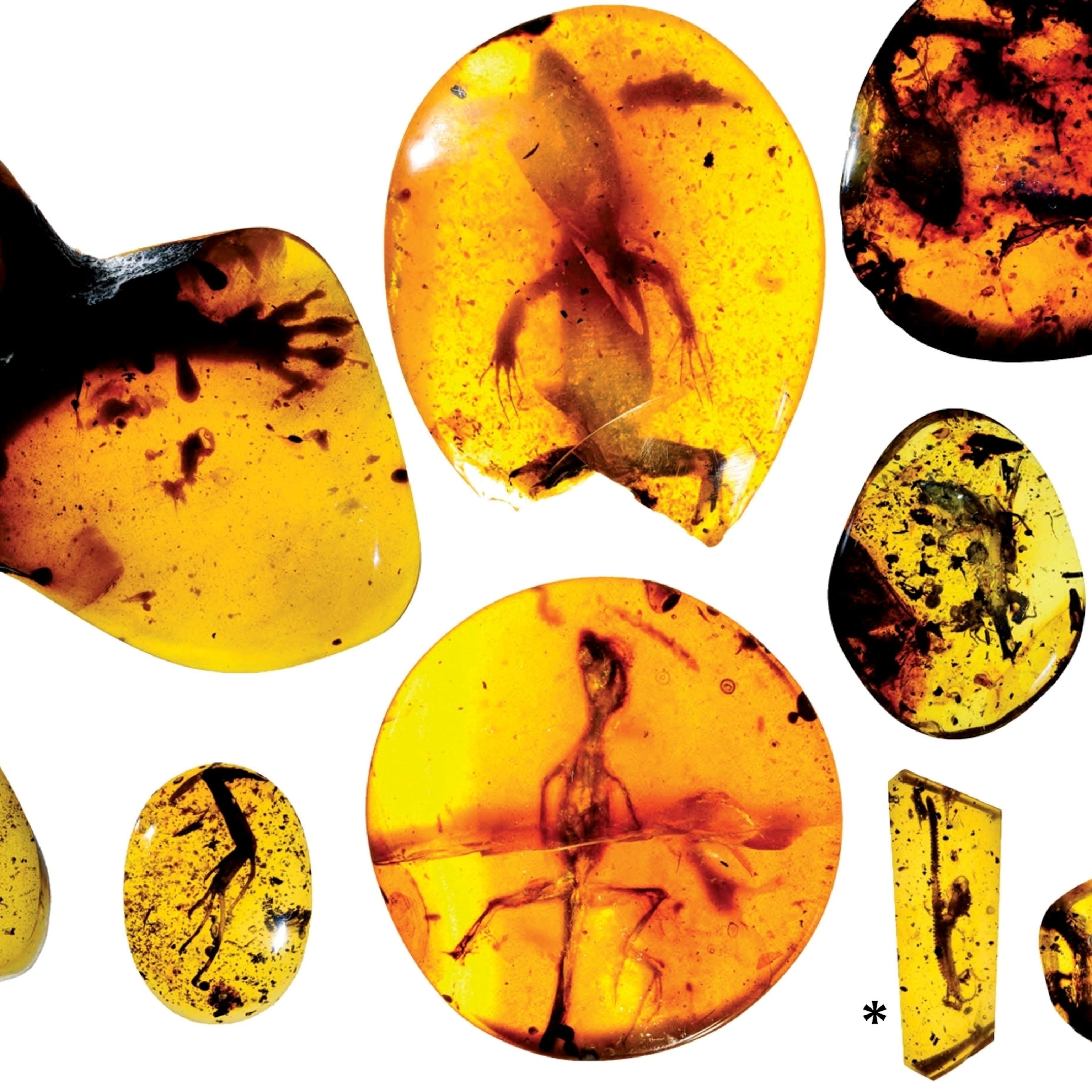

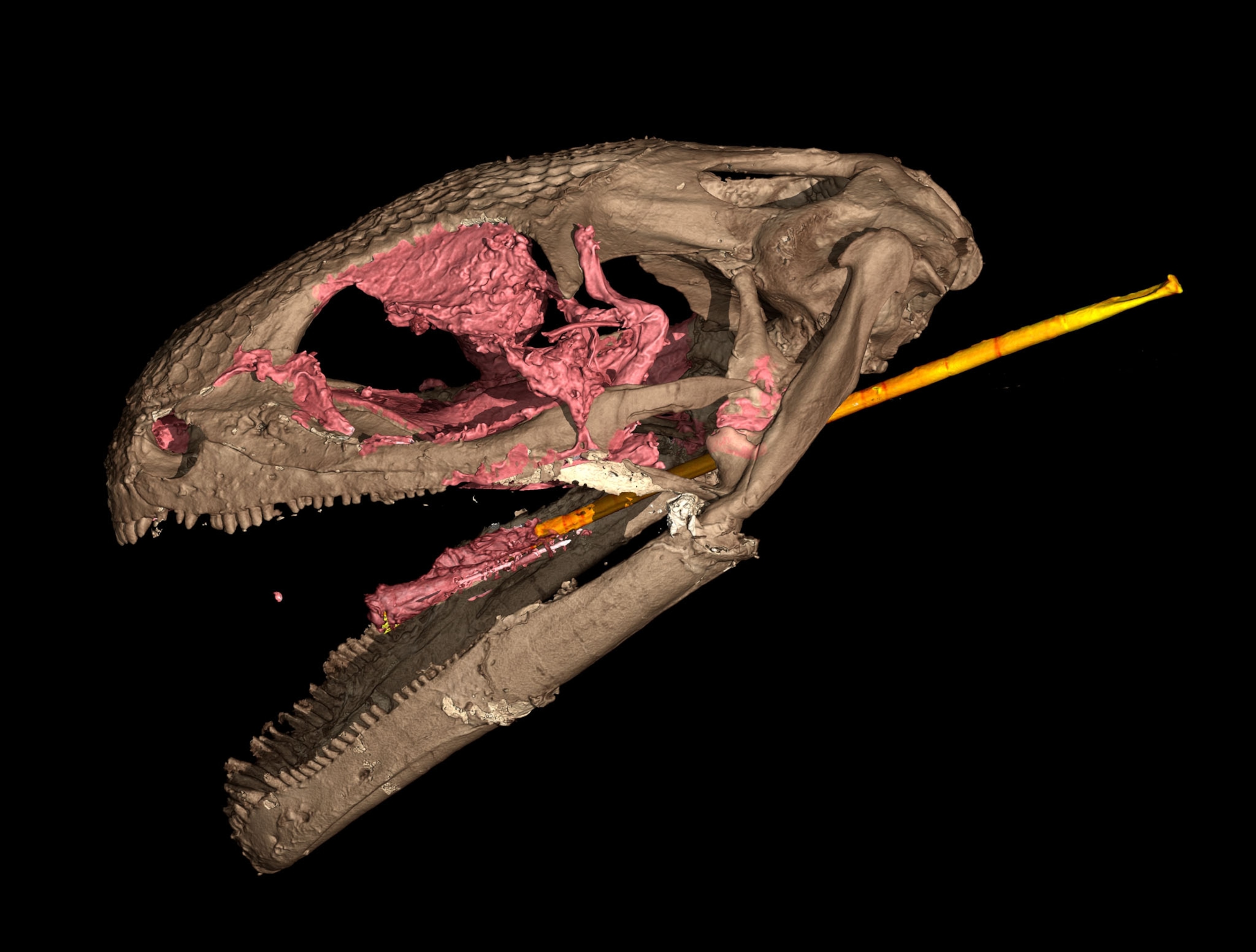

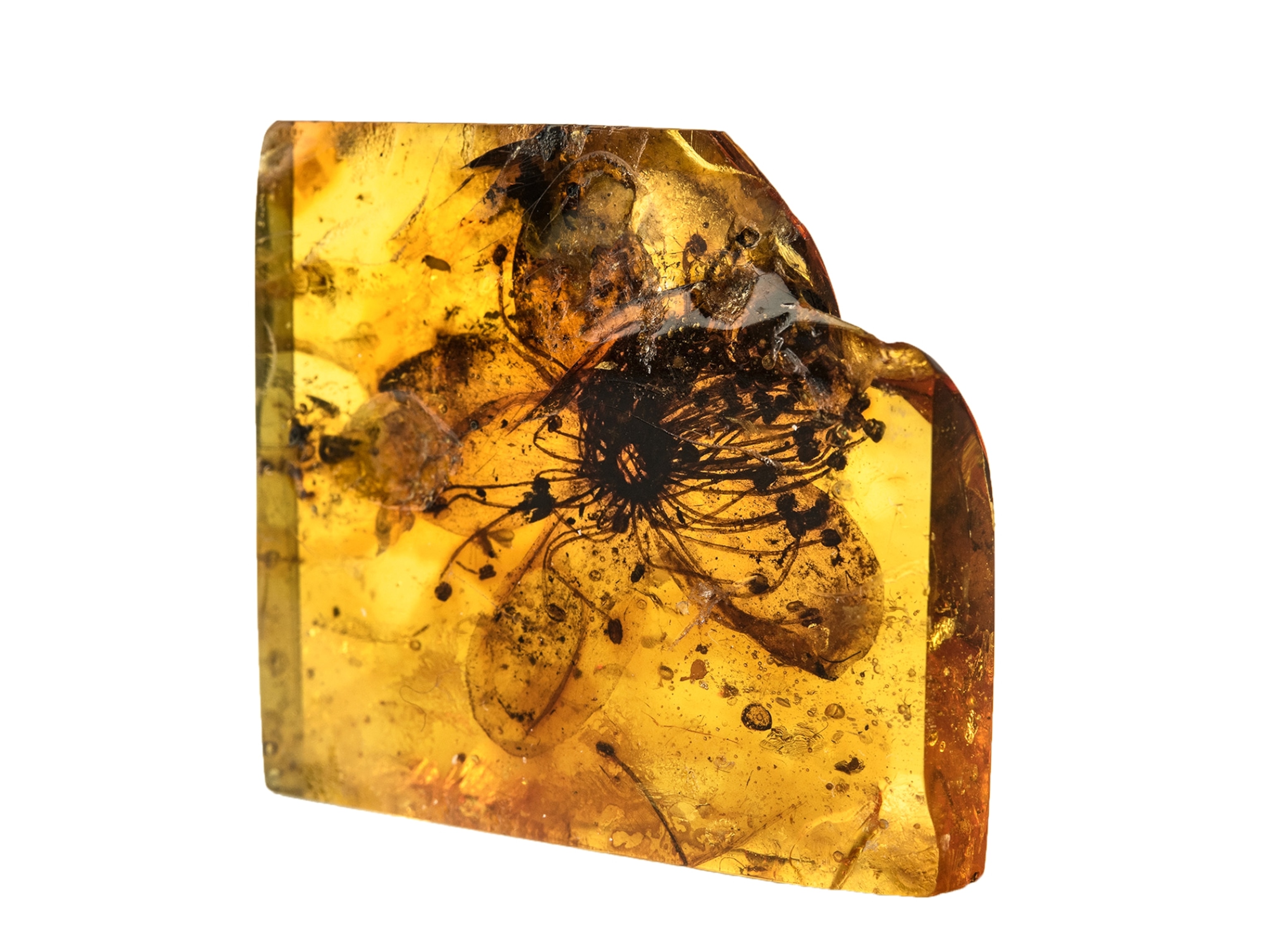

Ancient bug zapper

An amber-entombed fossil with an exquisitely preserved skull—even some muscles intact—is the oldest known example of a slingshot tongue, found in amphibians called albanerpetontids. Details about “albies” have been elusive; another albie fossil previously was misidentified as its distant cousin the chameleon. But new analysis by Sam Houston State University researcher Juan Daza and his colleagues identified this fossil, above,* from Myanmar, as a new albie species that lived 99 million years ago. Writing in Science, Daza’s team added to albies’ profile: Lizardlike, with scales and claws, likely living in or around trees, these sit-and-wait predators used their long, powerful tongues to nab small invertebrates. —Dina Fine Maron