Mister Big

Move over, T. rex: The biggest, baddest carnivore to ever walk the Earth is Spinosaurus.

On the evening of March 3, 2013, a young paleontologist named Nizar Ibrahim was sitting in a street-front café in Erfoud, Morocco, watching the daylight fade and feeling his hopes fade with it. Along with two colleagues, Ibrahim had come to Erfoud three days earlier to track down a man who could solve a mystery that had obsessed Ibrahim since he was a child. The man Ibrahim was looking for was a fouilleur—a local fossil hunter who sells his wares to shops and dealers. Among the most valued of the finds are dinosaur bones from the Kem Kem beds, a 150-mile-long escarpment harboring deposits dating from the middle of the Cretaceous period, 100 to 94 million years ago. After searching for days among the excavation sites near the village of El Begaa, the three scientists had resorted to wandering the streets of the town in hopes of running into the man. Finally, weary and depressed, they had retired to a café to drink mint tea and commiserate. “Everything I’d dreamed of seemed to be draining away,” Ibrahim remembers.

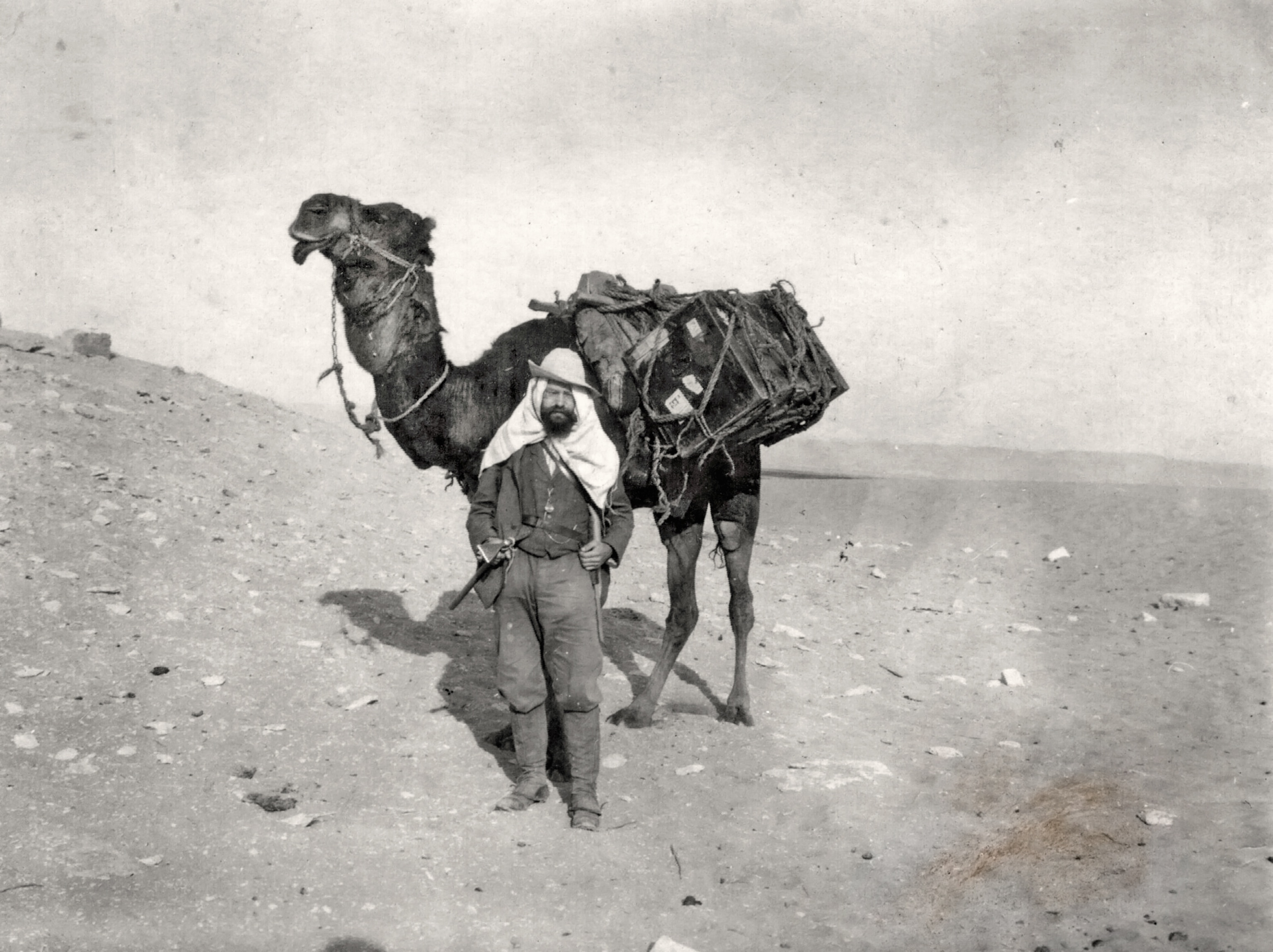

Ibrahim’s dreams were inextricably entangled with those of another paleontologist who had ventured into the desert a century earlier. Between 1910 and 1914 Ernst Freiherr Stromer von Reichenbach, a Bavarian aristocrat, and his team made several lengthy expeditions into the Egyptian Sahara, at the eastern edge of the ancient riverine system of which the Kem Kem forms the western boundary. Despite illness, desert hardships, and the gathering upheaval of World War I, Stromer found some 45 different taxa of dinosaurs, crocodiles, turtles, and fish. Among his finds were two partial skeletons of a remarkable new dinosaur, a gigantic predator with yard-long jaws bristling with interlocking conical teeth. Its most extraordinary feature, however, was the six-foot sail-like structure that it sported on its back, supported by distinctive struts, or spines. Stromer named the animal Spinosaurus aegyptiacus.

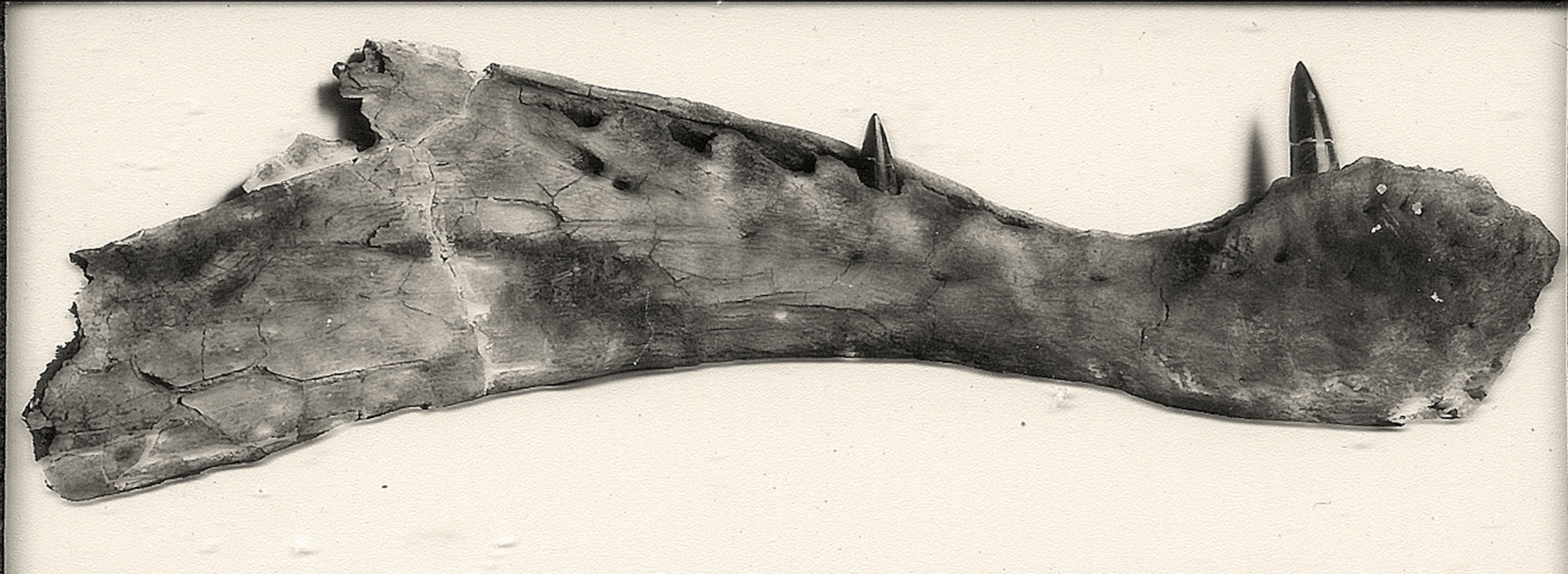

Stromer’s discoveries, prominently displayed in the Bavarian State Collection for Paleontology and Geology in central Munich, made him famous. During World War II he tried desperately to have his collection removed from Munich, out of range of Allied bombers. But the museum director, an ardent Nazi who disliked Stromer for his outspoken criticism of the Nazi regime, refused. In April 1944 the museum and nearly all of Stromer’s fossils were destroyed in an Allied air raid. All that was left of Spinosaurus were field notes, drawings, and sepia-toned photographs. Stromer’s name gradually faded from the academic literature.

Ibrahim, who grew up in Berlin, first encountered Stromer’s bizarre colossus in a German children’s book on dinosaurs. From that day on, dinosaurs haunted him. He made three-toed theropod tracks at the beach, and his favorite cookies were shaped like Triceratops and Tyrannosaurus rex. He visited paleontological collections around Germany and built an impressive collection of models and fossil casts.

He encountered Stromer’s work again while studying paleontology at the University of Bristol. “The breadth and the depth of his work was incredible and inspired me to be ambitious in my own research,” Ibrahim says. While most doctoral students explore a tightly circumscribed topic, Ibrahim’s 836-page dissertation at University College Dublin described the entire fossil record of the Kem Kem.

Fieldwork for his Ph.D. brought him to Erfoud several times. On a visit in 2008, when Ibrahim was 26, a Bedouin showed him a cardboard box containing four blocks of distinctive purplish stone streaked with yellow sediment. Protruding from the rock were what looked like a dinosaur hand bone and a flat blade of bone with an unusual milk-white cross section. Like all fossils heedlessly torn from their surrounding geology, the bones’ scientific value was dubious. Ibrahim offered to buy them anyway, thinking they might be of some use for the University of Casablanca’s fledgling paleontology collection.

Ibrahim would come to understand their potentially enormous significance during a visit the next year to the Natural History Museum in Milan, Italy. Researchers Cristiano Dal Sasso and Simone Maganuco showed him a partial skeleton of a large dinosaur they had recently received from a fossil dealer. The specimen was laid out on tables in the basement: leg bones, ribs, numerous vertebrae, and several tall, distinctive dorsal spines. Ibrahim was astounded. It was clearly a Spinosaurus,substantially more complete than Ernst Stromer’s lost specimens. Dal Sasso and Maganuco told him that the dealer thought it had been excavated at a site called Aferdou N’Chaft, near El Begaa. The bones were still encrusted with the rock they’d been buried in, a purplish sandstone with yellow streaks. Lifting a chunk of spine, Ibrahim saw a familiar white cross section.

“I realized the bones I’d bought in Erfoud must be Spinosaurus—that odd flat bone was a piece of spine,” Ibrahim remembers. It then occurred to him that the scrappy fossils from Erfoud and the magnificent specimen in Milan might belong to the same individual. If so, and if he could pinpoint the exact spot where the fossils had been buried, they could become a Rosetta Stone for understanding Spinosaurus and its world.

To find the spot, however, he would first have to do something tougher than finding a needle in a haystack: find a Bedouin in the desert.

“I didn’t know his name, and all I could remember was that he had a mustache and was wearing white,” Ibrahim says. “Which in Morocco didn’t narrow things down much.”

Four years would pass before Ibrahim could return to Erfoud and attempt to track down his man. Along with Samir Zouhri from the Université Hassan II, Casablanca, and David Martill from the University of Portsmouth in the U.K., Ibrahim visited several excavation sites, starting with Aferdou N’Chaft. Nobody seemed to recognize Ibrahim’s photos of the Spinosaurus fossils or to know the Bedouin from Ibrahim’s vague description. After searching the streets of Erfoud on their last day, they had finally given up and slumped down in a café.

As they sat staring blankly at the people passing on the street, a man with a mustache wearing white walked by. Ibrahim and Zouhri exchanged glances, then hopped up and gave chase. It was the same man. He confirmed that he’d chipped the bones out of a rock face over two months of hard work, first uncovering the bones he had sold to Ibrahim, then finding more farther into the hillside, which he had eventually sold to a fossil dealer in Italy for $14,000. When they asked if he would show them the findspot, however, the man at first refused. Ibrahim, who speaks Arabic, explained how essential it was to know where the bones had been found and why that knowledge would someday allow the dinosaur to return to Morocco, as part of a new museum collection in Casablanca. The Bedouin, who had listened in silence, nodded.

“I will show you,” he said.

After driving their battered Land Rover through the palm plantation north of Erfoud, the man led them on foot along a dry wadi and up a steep bluff. Strata in the surrounding cliffs showed that great meandering rivers had flowed there a hundred million years ago.

Finally they reached a gaping hole in a hillside, which had once been a riverbank.

“There,” said the Bedouin.

Ibrahim climbed in, noting the walls of purplish sandstone with yellow streaks.

For Ernst Stromer, Spinosaurus was a lifelong enigma. He struggled for decades to understand the strange creature from the pieces of two skeletons that his team had found. He first speculated that its long neural spines might have supported a shoulder hump like a bison’s, then later surmised that they were part of a dorsal sail, like those sported by some modern lizards and chameleons. He noted that Spinosaurus’s narrow jaws were unique among predatory dinosaurs. So were its teeth—most carnivorous theropods had bladelike, serrated teeth, but these were smooth and conical and resembled those of a crocodile. Stromer concluded, with evident perplexity and perhaps a bit of frustration, that the animal was “highly specialized,” without saying what it was specialized for.

Spinosaurus was part of a larger mystery, sometimes called Stromer’s Riddle, that he’d first observed in North African fossils. In nearly all ancient and modern ecosystems, plant-eaters greatly outnumber meat-eaters. Yet along the northern edge of the African continent, from Stromer’s Egyptian excavations in the east to the Kem Kem beds of Morocco in the west, the fossil record suggests the opposite. Indeed, this region was inhabited by three enormous meat-eaters, each of which would have been an apex predator elsewhere: swift, 40-foot-long Bahariasaurus;40-foot Carcharodontosaurus, like an African T. rex; and Spinosaurus, perhaps biggest and certainly oddest of all. Stromer speculated that large herbivores had probably been present—what else had the carnivores eaten?—but not many of their bones had turned up yet. Other scientists have suggested the paradox is merely sampling error, caused by geological processes that mix fossils of different ages together—or by fossil hunters who preferentially select large, spectacular carnivores because they sell better.

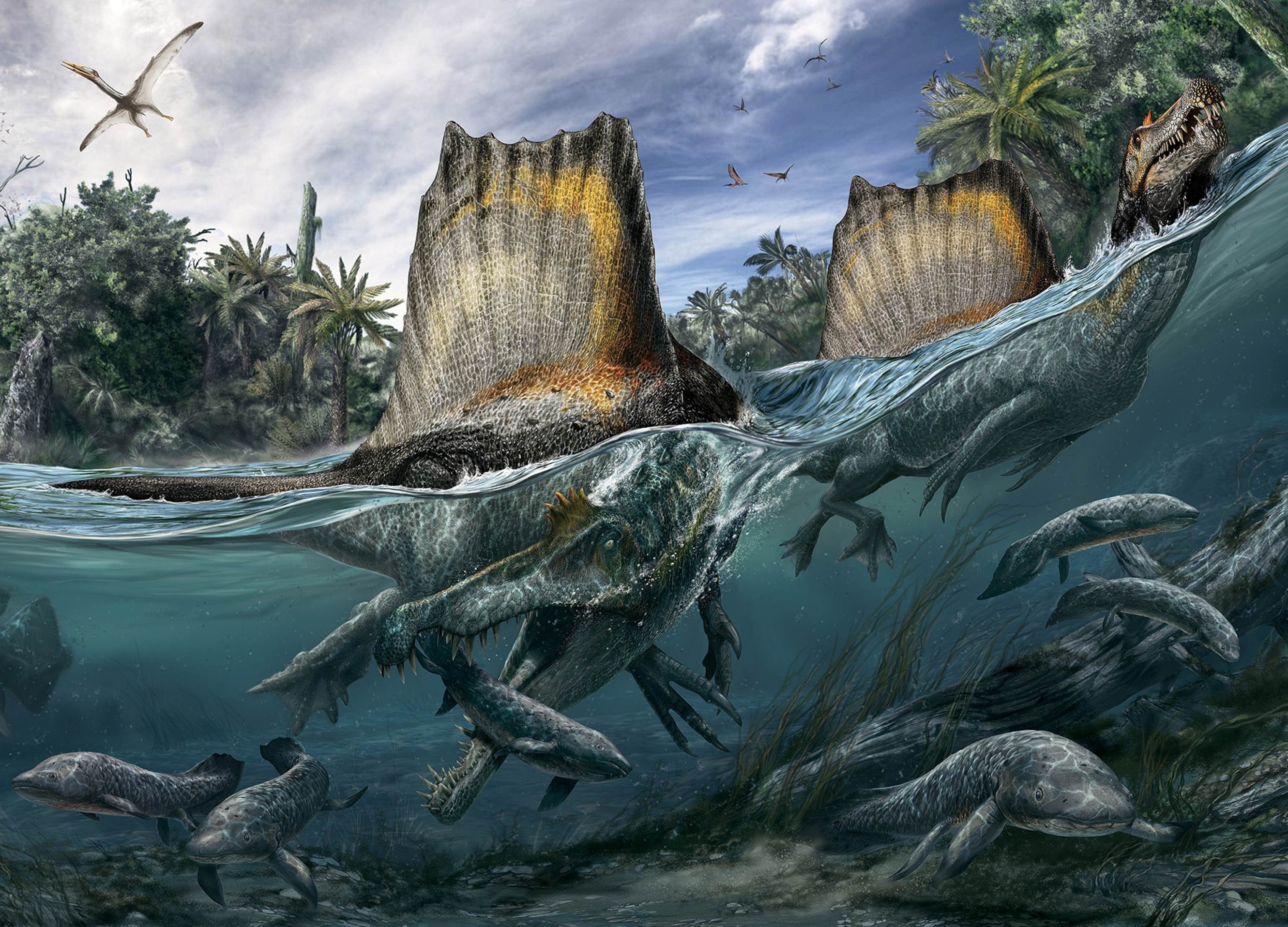

With a new Spinosaurus in hand and knowledge of the precise location where it had been found, Nizar Ibrahim was in a position to find a more satisfying answer to Stromer’s Riddle. At first glance, however, the new bones made the animal all the more puzzling. For starters, the surface of the dorsal spines was smooth, which meant they were unlikely to have supported a lot of soft tissue like a hump. The spines had few channels for blood vessels, so it seemed unlikely that they were used to regulate body temperature, as other researchers had conjectured. The ribs were equally dense and tightly curved, creating an unusual barrel-shaped torso. The neck was long, the skull enormous. But the jaws were surprisingly slender and elongated, with a peculiar arched snout tip speckled with tiny pits. The forelimbs and thoracic girdle were bulky, while the hind limbs were disproportionately short and slender.

“Spinosaurus is incredibly front heavy,” says paleontologist Paul Sereno, Ibrahim’s postdoctoral adviser at the University of Chicago and the discoverer of several notable North African dinosaurs, including Suchomimus, a relative of Spinosauruswith long, crocodile-like jaws. “It’s like a cross between an alligator and a sloth.”

Ibrahim had a life-size image of the animal’s skull on the wall in his office that he often stared at, unfocusing his eyes and struggling to imagine the enormous body stretching out behind. “I tried to see all the bones, the muscles, the connective tissue, everything. Sometimes it was there for an instant, then it vanished, like a mirage. My brain couldn’t quite compute all that complexity.”

But a computer might. Together with Simone Maganuco at the Milan museum and Tyler Keillor, a fossil preparator and paleoartist at the University of Chicago, Ibrahim set about digitally reconstructing the dinosaur. They CT-scanned each bone of their specimen at the University of Chicago Medical Center and Maggiore Hospital in Milan, then added other body parts by scanning photos from museum specimens in Milan, Paris, and elsewhere, as well as digital images of Stromer’s photographs and sketches, scaling up the remains of younger individuals to adult size in some cases. Keillor, an expert in the digital modeling program ZBrush, sculpted missing bones in ZBrush’s “digital clay,” mapping his work with scans of the same anatomy in related spinosaurid dinosaurs like Suchomimus and Baryonyx. By painstakingly shaping and spacing the 83 vertebrae in their model, they determined that an adult Spinosaurus measured 50 feet from nose to tail. There had been claims that Spinosaurus was the largest carnivore to ever walk the Earth. This confirmed it. (The largest T. rex is 40.5 feet head to tail.)

Next they wrapped the skeleton in digital skin to create a dynamic model, which allowed them to estimate the animal’s center of gravity and body mass, the better to understand how it moved. Their analysis led to a remarkable conclusion: Unlike all other predatory dinosaurs, which walked on their hind legs, Spinosaurus may have been a functional quadruped, also enlisting its heavily clawed forelimbs to walk.

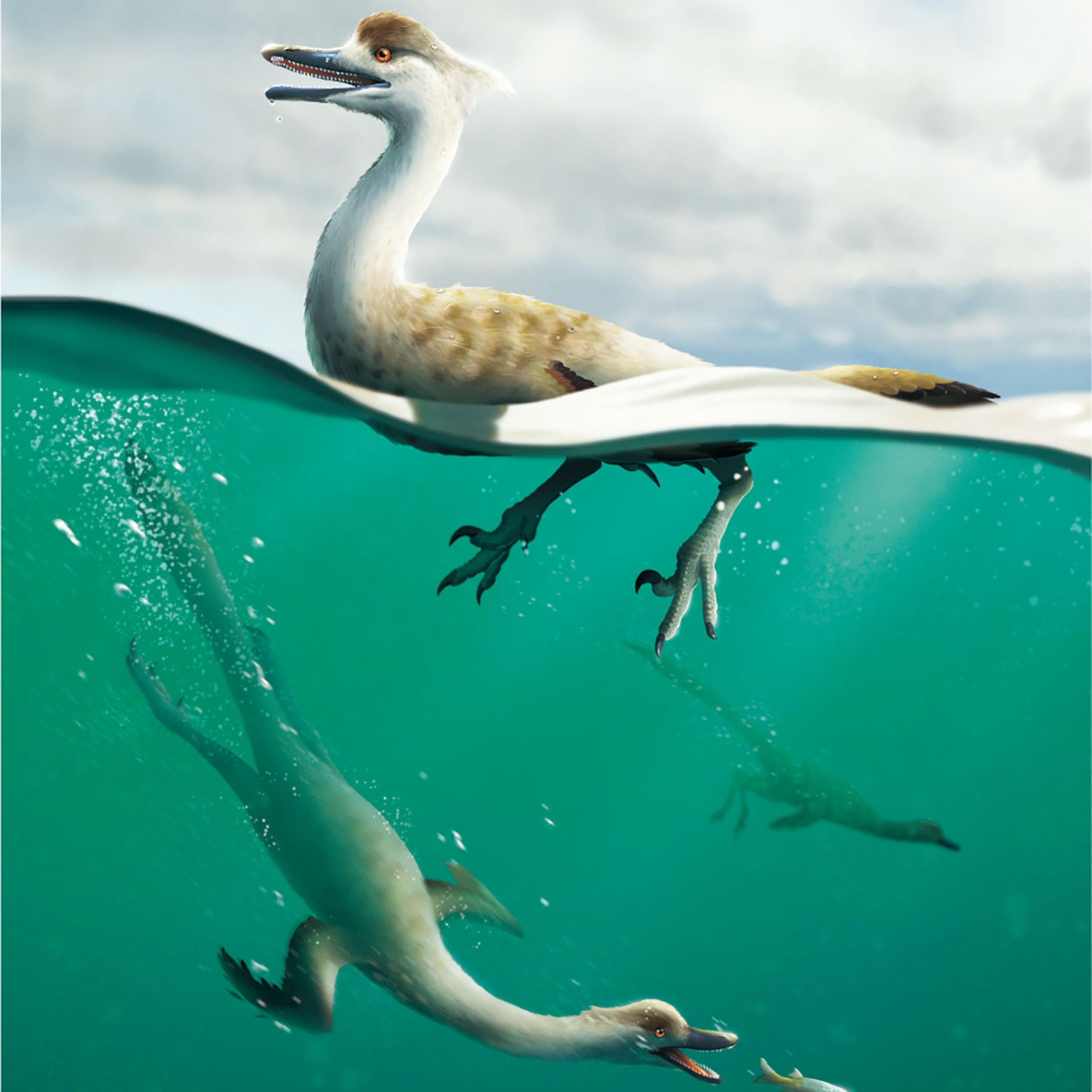

The peculiarities of the creature began to make real sense, however, only when Ibrahim and his colleagues viewed Spinosaurus from an entirely different perspective: as a dinosaur that spent most of its time in the water. The nostrils are set high on the skull toward the eyes, allowing the animal to breathe with much of its head submerged. The barrel-shaped torso recalls dolphins and whales, and the density of its ribs and long bones is similar to that of another aquatic mammal, the sea cow. The hind legs, so oddly proportioned for walking, would have been perfect for paddling, particularly if the flat claws in its broad hind feet had been connected with webbing like a duck’s, as the researchers suspect. Its long, slender jaws and smooth, conical, croc-like teeth would have been devastatingly effective at snaring fish, and the pits in its snout, also present in crocs and alligators, probably housed pressure sensors to detect prey in murky water. Ibrahim imagines Spinosaurushunting a bit like a heron, leaning forward and snapping up fish with its long muzzle.

This new vision of Spinosaurus as an aquatic dinosaur suggests a possible solution to Stromer’s Riddle. The river along which this animal died was one of many large waterways in a vast fluvial system that occupied much of North Africa in the Cretaceous. If the carnivores here were big, so too was the aquatic life, whose remains are common in the Kem Kem deposits: 8-foot lungfish, 13-foot coelacanths, 25-foot sawfish, and similarly outsize turtles. These animals would have made healthy meals for even the largest predator, obviating the need for abundant large herbivores to balance the food web.

All this came home to Ibrahim with full force when he saw the culminating phase of the digital dinosaur project: a life-size Spinosaurus skeleton in high-density polystyrene foam, created from the computer model in part by a 3-D printer. The skeleton is mounted in a swimming posture, which Ibrahim thinks it may have employed as much as 80 percent of the time. “I wish Ernst Stromer could see this model, which shows just how much of a specialized swimmer Spinosaurus had become. It would have made him smile.”