Exploring Deep Sea and Deep Space Are Surprisingly Similar

Sylvia Earle and Neil deGrasse Tyson talk about the seas and stars.

This interview was drawn from a taping for a StarTalk television episode that will air November 19 at 11/10c on National Geographic.

Neil deGrasse Tyson: Sylvia, I heard a rumor that you were born underwater. And that you had gills, and then you just had to pretend you were human and came out, and now it’s just a charade when you’re on dry land.

Sylvia Earle: I wish that was so!

NT: What happened to you early in life where all of a sudden being on dry land was not the priority?

SE: Well, I got knocked over by a wave when I was a little kid, on the New Jersey shore. I couldn’t breathe—and then suddenly my toes touched the bottom and my head came out, and I realized that was kind of cool. It was fun. Then my family moved to Florida when I was 12, and my backyard was the Gulf of Mexico. You know, kids are naturally explorers. They are scientists from the get-go, always asking questions. Everything is new; everything is wonderful.

NT: See, as a city kid, all I can think of about the ocean is, I can’t breathe there.

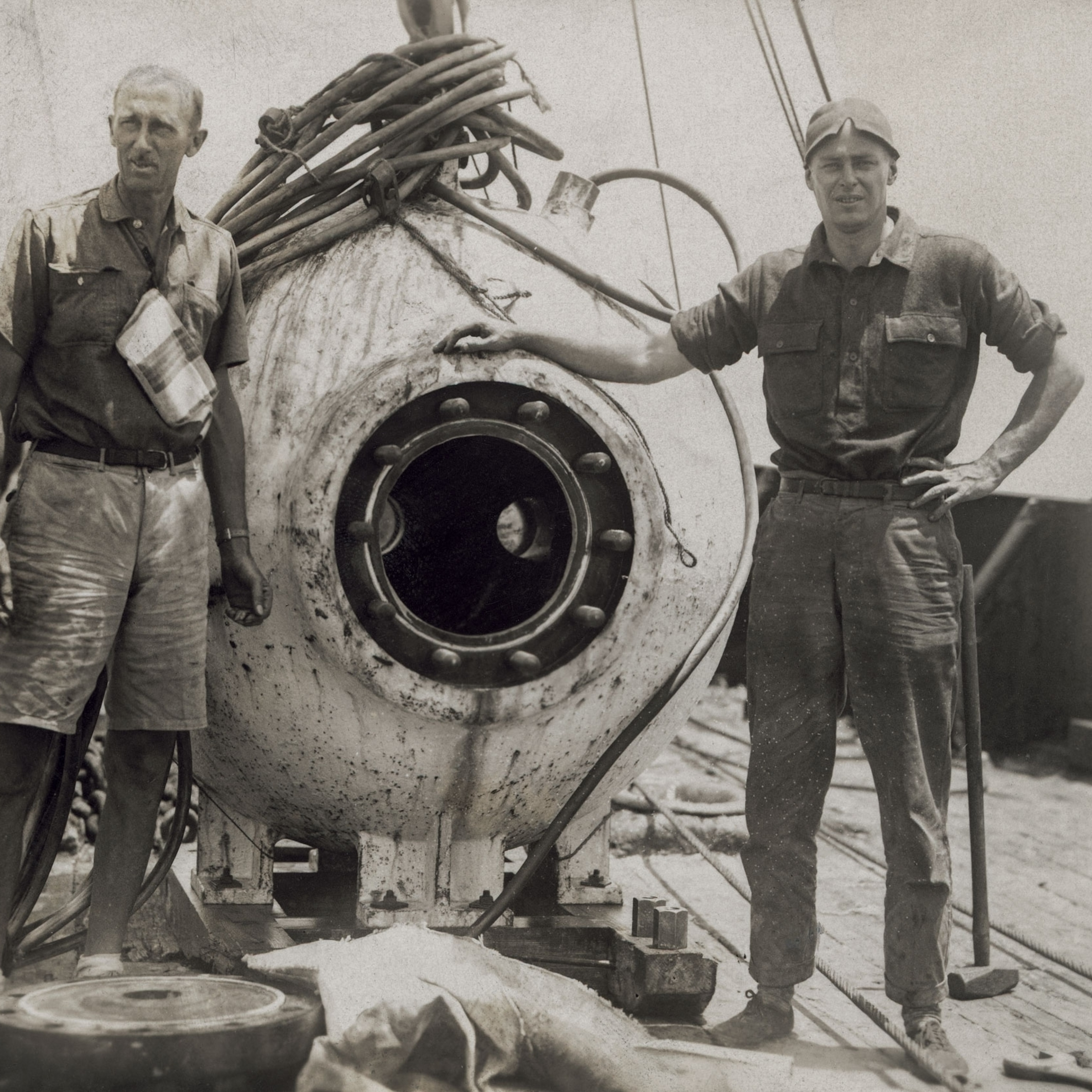

SE: But now you can. Inside a submarine—or thanks to the technologies that were developed before either of us came along. They started in the 1800s to supply air by a compressor down a tube into a helmet of sorts that people could wear. It’s one way that sea and space come together: life-support systems.

NT: We have an interesting duality here with the challenges of accessing and surviving underwater and the challenges of accessing and surviving in space. Of course, it’s far more expensive to go into space than to the bottom of the ocean.

SE: Getting to the bottom of the ocean is easy. Sometimes you don’t come back …

NT: Getting to the deepest point of the ocean is a trivial exercise—but doing it without dying, that’s the challenge?

SE: It is. And only three people have made that journey to the deepest place, 11 kilometers [or seven miles] down.

NT: This is the Mariana Trench, off of the Philippines.

SE: That’s right. The first excursion was Jacques Piccard and Don Walsh in 1960. Then in 2012, filmmaker [and National Geographic Explorer-in-Residence] James Cameron contributed resources to build a submersible for one person, which is pretty gutsy. It went to the depths of the ocean and cruised around for nearly three hours. But most of the ocean has never been seen by anybody.

NT: Maybe it doesn’t have the romance of the sky and the universe.

SE: I beg your pardon.

NT: Oops. I said that to the wrong person. OK, maybe it doesn’t feel as limitless as the night sky.

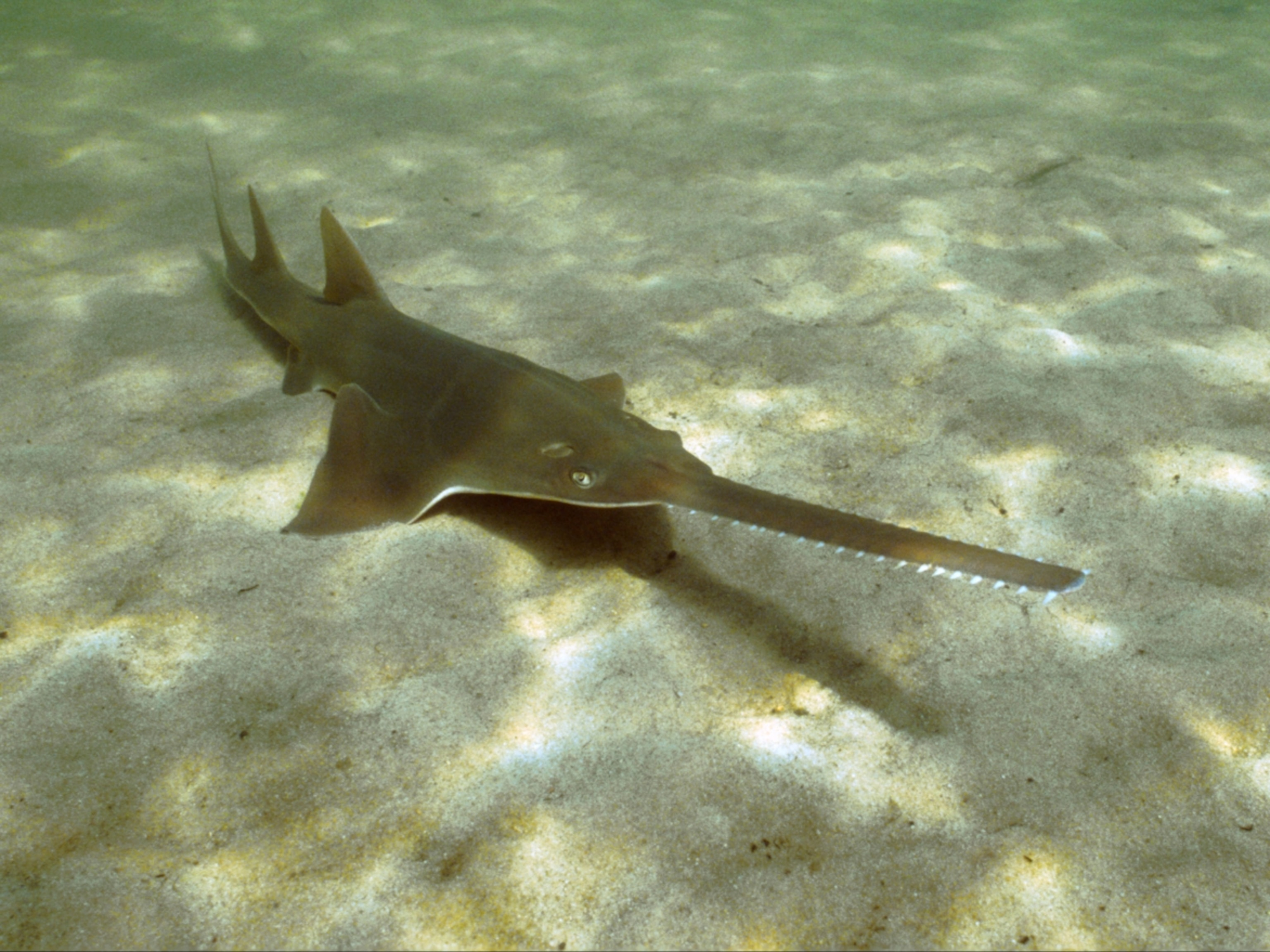

SE: The problem is, people think that because it’s our blue backyard, we know everything there is to be known. You look at the surface today, it likely looks pretty much the way it did a thousand years ago. But 90 percent of the ocean’s fisheries have been overfished or fully exploited, mostly during the past 30 years. And though there are signs of coral reefs recovering, up to two-thirds of them have been seriously damaged.

NT: Maybe it’s out of sight, out of mind. You have this huge support to stop the deforestation of rain forests, to preserve lakes and rivers and wetlands. Is it because they’re just more visible to us?

SE: Of course. And the thought is that the ocean is so big, so vast, so resilient, it’s too big to fail. Right? But now we know it is failing. And why should we care about that? You know, who cares if there aren’t any more tuna?

NT: You’ll just eat the next fish.

SE: That’s been the thought—but now there are no more “nexts” to go to. I mean, some fish species are decades old. They’re not like a chicken that takes only months to mature. To make a pound of chicken takes maybe two pounds of plants; for a pound of cow, up to 20 pounds of plants. But the tuna gobbles decent-size fish that have eaten other fish, that have eaten other fish, every step of the way down to the plants. So that’s tens of thousands of pounds of plankton funneled through this long and twisted food chain to a tuna, which is caught to yield a little piece of sushi that you don’t really need. It’s a choice.

NT: You’re bumming me out. I’m not going to eat ever again after this conversation.

SE: You just have to eat with respect and know what you’re eating. That’s the key.

NT: So now we have to rethink our relationship to this planet.

SE: Correct. People say, why should I care about the ocean? Because the ocean touches you, whoever you are or wherever you are, with every breath you take. It’s where most of the Earth’s oxygen is generated, replenished by these tiny little green guys in the ocean, like phytoplankton. So we need to think of ourselves as a part of the system rather than the big boss of the universe. Now I have a question for you: When do we go diving in an ocean submarine?

NT: I want to make sure the submarine has done that before and it came back safely and there aren’t hash marks on the side of people who died trying.

SE: Where’s your sense of adventure?

NT: I like adventure, but I let other people get the bugs out. Then I’m there.

SE: All right, let’s make it happen. Let’s figure it out.

NT: We’ll make a pact. Excellent. None of these one-way trips to the bottom of the ocean—a round-trip.

SE: A round-trip, yes. Those are the ones that count.