Surrounded by sounds—of music, science, animals, and more

Novel noisemakers in nature include spiderwebs that can vibrate musically, whale songs that serve as ocean soundings, and more.

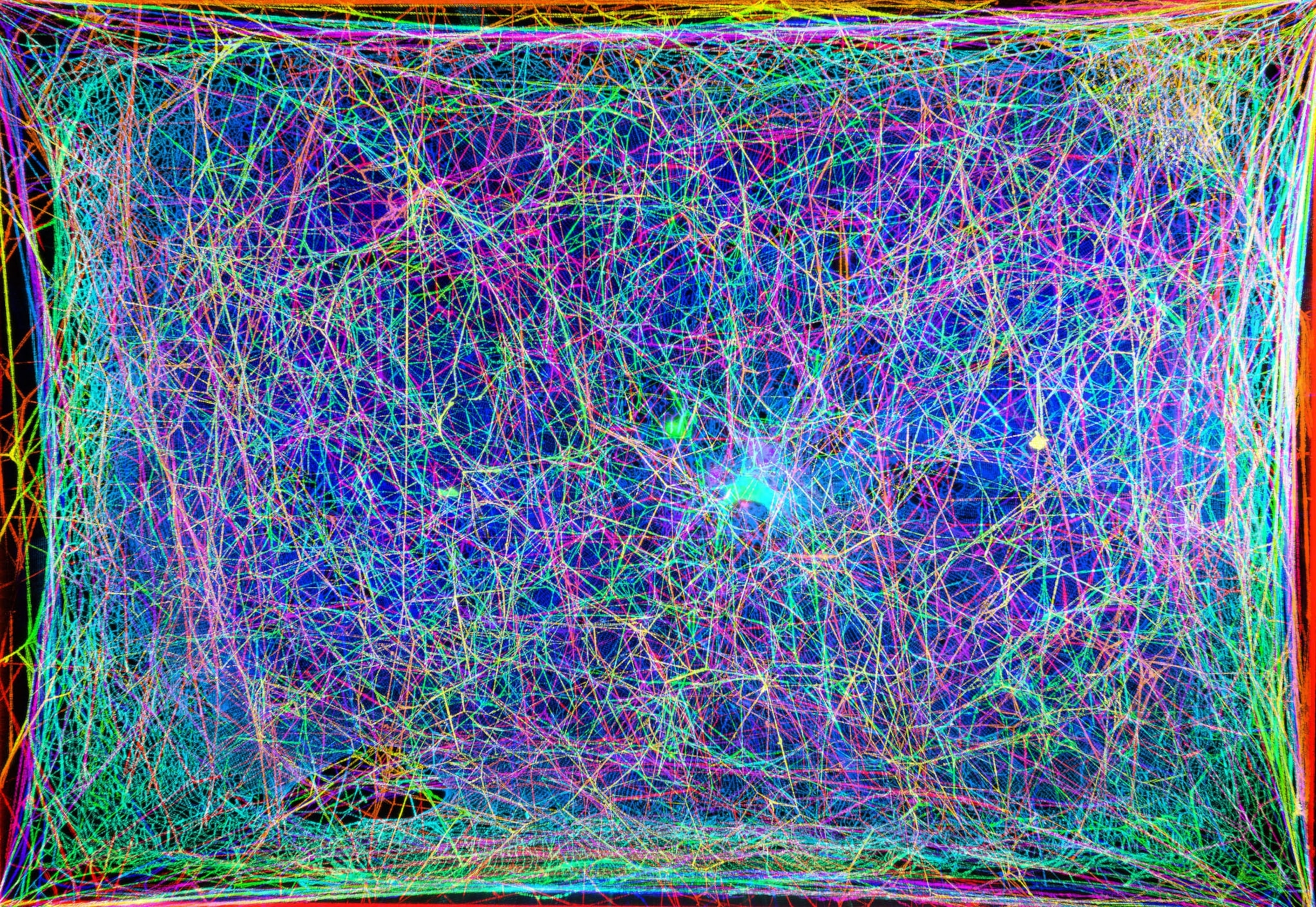

Finding music in vibrations of spiderweb strands

Lacking sharp eyesight, spiders use their legs to feel vibrations in their webs. A web’s silken strands have different lengths and tensions and, as a result, different frequencies. The resident spider is attuned to those frequencies to detect prey, potential mates, or threats. Now, a group of scientists at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology aims to convey a bit of that Spidey sense to humans. With 3D laser imaging based on cobweb cross sections, the MIT team mapped the web of a tropical tent-web spider. To the strands, the scientists assigned musical tones audible to humans. They also built a virtual reality interface that lets users “play” the spiderweb like an eerie-sounding stringed instrument. “We’re trying to give the spider a voice,” said MIT’s Markus Buehler—and, maybe someday, communicate with the arachnid via vibrations. —Hicks Wogan

Snake uses its rattle speed to fool foes

If you can hear the raspy ch-ch-ch produced by a rattlesnake’s tail, then you’ve already wandered too close. Or is that just what the snake wants you to think? By analyzing sound waves, scientists learned that western diamondback rattlesnakes vibrate their tails slowly when a threat is far away but shift into a quicker, high-frequency rattle as a threat nears. This acceleration tricks the human ear into thinking the serpent is closer than it actually is. —Jason Bittel

What’s a songbird without its song?

The regent honeyeater (Anthochaera phrygia) is a critically endangered songbird in southeastern Australia. Only a few hundred are left, and some young males aren’t around older ones enough to learn their songs. A research team based in Canberra recently reported that 27 percent of male honeyeaters were singing flawed renditions, while 12 percent didn’t know their mating calls at all and had adopted those of other species—not what female honeyeaters want to hear. The team has exposed captive young birds to older birds’ recorded songs—and even to wild-caught older males—in hopes that this music therapy will teach youngsters the right tunes to preserve the species. It’s a reminder that populations and cultures rise and fall together, like the notes of a song. —HW

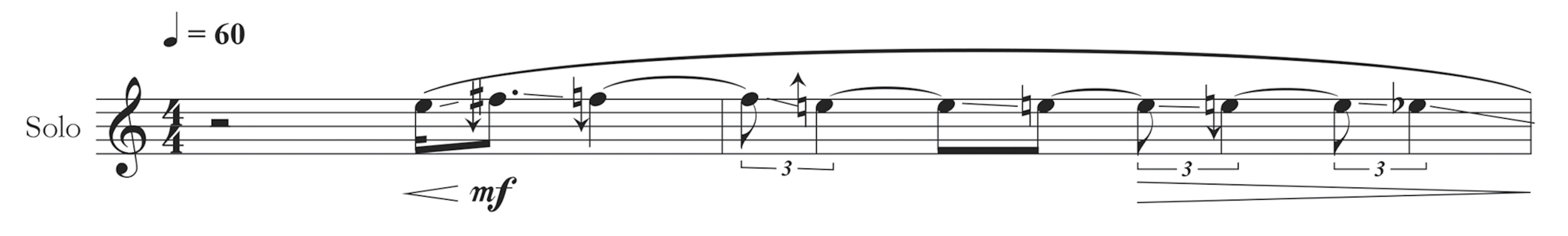

Noting the calls of the wild

The whistling of a nightingale. The howl of a gray wolf. The kazoo-like calls of emperor penguins. To keep his ear trained during a COVID-19 lockdown, French-German composer Alexander Liebermann began transcribing sounds of the animal kingdom into sheet music that he posts online. What started as a joke has resonated with fans, he notes, and become “something bigger.” —HW

Whale songs act as an ultrasound of seafloor

Long regarded as interference on quake recordings, cetacean calls could help map the Earth’s crust.

From locations on the ocean floor, seismographs relay data to scientists on land who monitor earthquakes. Besides picking up seismic activity, the instruments often capture the songs of nearby whales. Typically, researchers delete those whale sounds during analysis. But scientist Václav Kuna, then with Oregon State University, hit upon a new application as he listened to the calls of a fin whale, which can be as loud as a large ship and detected up to 600 miles away. Seismographs record the initial signal from a fin whale and then an echo after the sound has penetrated the seafloor, gone as deep as one and a half miles beneath the floor, and bounced back upward. By studying the echoes’ frequencies, scientists can gain a type of low-resolution ultrasound of the Earth’s crust. It’s not unlike how energy companies deploy air guns to scan for underwater oil and gas deposits—except whale sounds are naturally occurring, free of charge, and less disruptive to marine life. In researcher Kuna’s view, “It’s a win-win.” —HW

The sounds of humanity

Latin pop in Peru, a call to prayer in Iran, the nightly news in Norway’s Arctic. All these sounds emanate from Radio Garden, a website that links to thousands of radio stations streaming live from places large and small—and bringing listeners to the most distant of destinations. With origins in a 2016 exhibition project commissioned by the Netherlands Institute for Sound and Vision, Radio Garden now aims to plant “seeds” of global connections through the sounds of humanity. —Jordan Salama

(Read more about how to travel the world—by radio.)

These stories appear in the December 2021 issue of National Geographic magazine.