The need to save more seeds, and other science news

Experts call for additional seed-saving methods, a pine forest accidentally escapes logging, and tree rings record earthquakes.

Saving seeds, by more means

An estimated 8 percent of plant species—including about a third of endangered and vulnerable ones—have recalcitrant seeds that won’t tolerate drying, says a study in the journal Nature Plants. That means typical seed bank processes won’t work for those species, so experts urge additional measures, such as cryopreservation, to guard against their extinction. —Hicks Wogan

Centuries-old survivors

In the late 1800s and early 1900s, loggers clear-cut pines in Minnesota’s North Woods—but some remain, thanks to a mapping error.

A surveying slipup 140 years ago spared a patch of old-growth pine forest in northern Minnesota from the saws and axes of the region’s logging boom. Now the trees—the kind that once filled the area’s famed North Woods—are estimated at up to 400 years old.

Most of the region’s forests may look mature, but many trees are less than a century old; settlers and lumber barons clear-cut much of the forest between the 1890s and 1920s. So how were more than 30 acres of old-growth pines missed? According to U.S. government records, in the winter of 1882, four surveyors headed into the thick forests to inventory land features. Cold and living roughly, they apparently rushed the job and made a mistake, categorizing as a lake the area that was actually forest acreage. Later, when loggers were bidding on that land, it was listed as being underwater and so was not pursued for logging rights.

That’s a boon to modern-day hikers. They can wander through what’s now called the Lost 40 and gaze up at the towering pines—one of which is the state’s largest living red pine at 120 feet tall and nearly 10 feet around. —Katie Thornton

From trees, a new way to pinpoint earthquakes

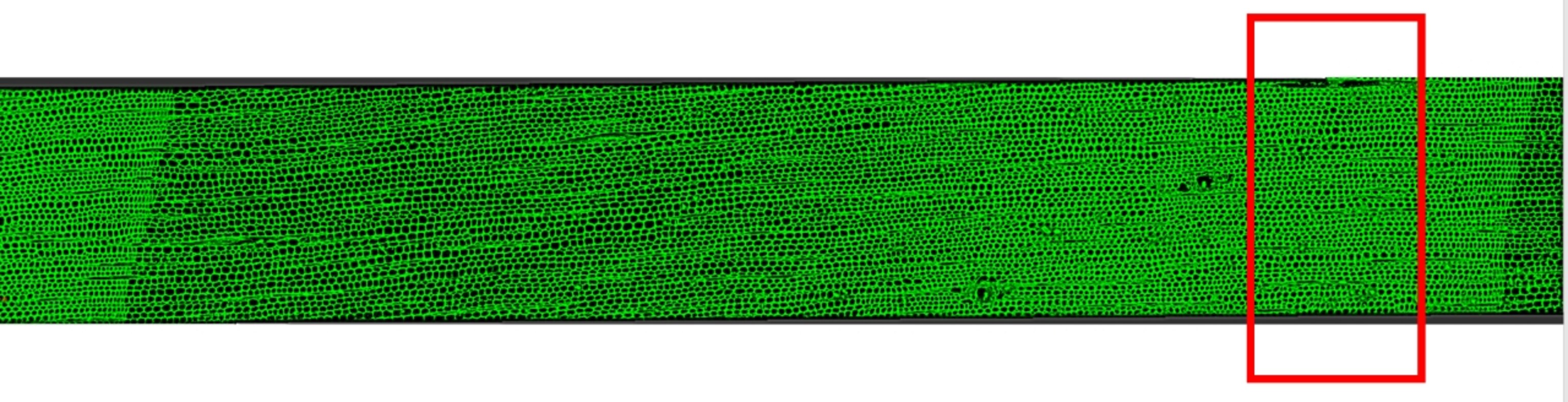

In Chile after a magnitude 8.8 earthquake, a team of scientists from U.S. and German research institutions noticed that streams in their valley work site had sped up. It’s known that earthquakes make soil more permeable and increase the downhill flow of groundwater. When the researchers later took core samples from pine trees in valleys and along ridges in a Chilean mountain range, measures of the tree rings’ cells (below) confirmed that valley trees with extra water after the earthquake had seen temporary growth spurts and that higher, drier trees had grown more slowly. In this way, the earthquake had left an imprint on trees. The researchers also have made a mark: The tree-ring technique can potentially date a seismic event to within weeks of its occurrence, more precise than the usual metric, the nearest year. —HW