Ghostwalking in Titanic

Wandering room to room through the sunken wreck, the explorer and filmmaker finds himself at home among the spirits.

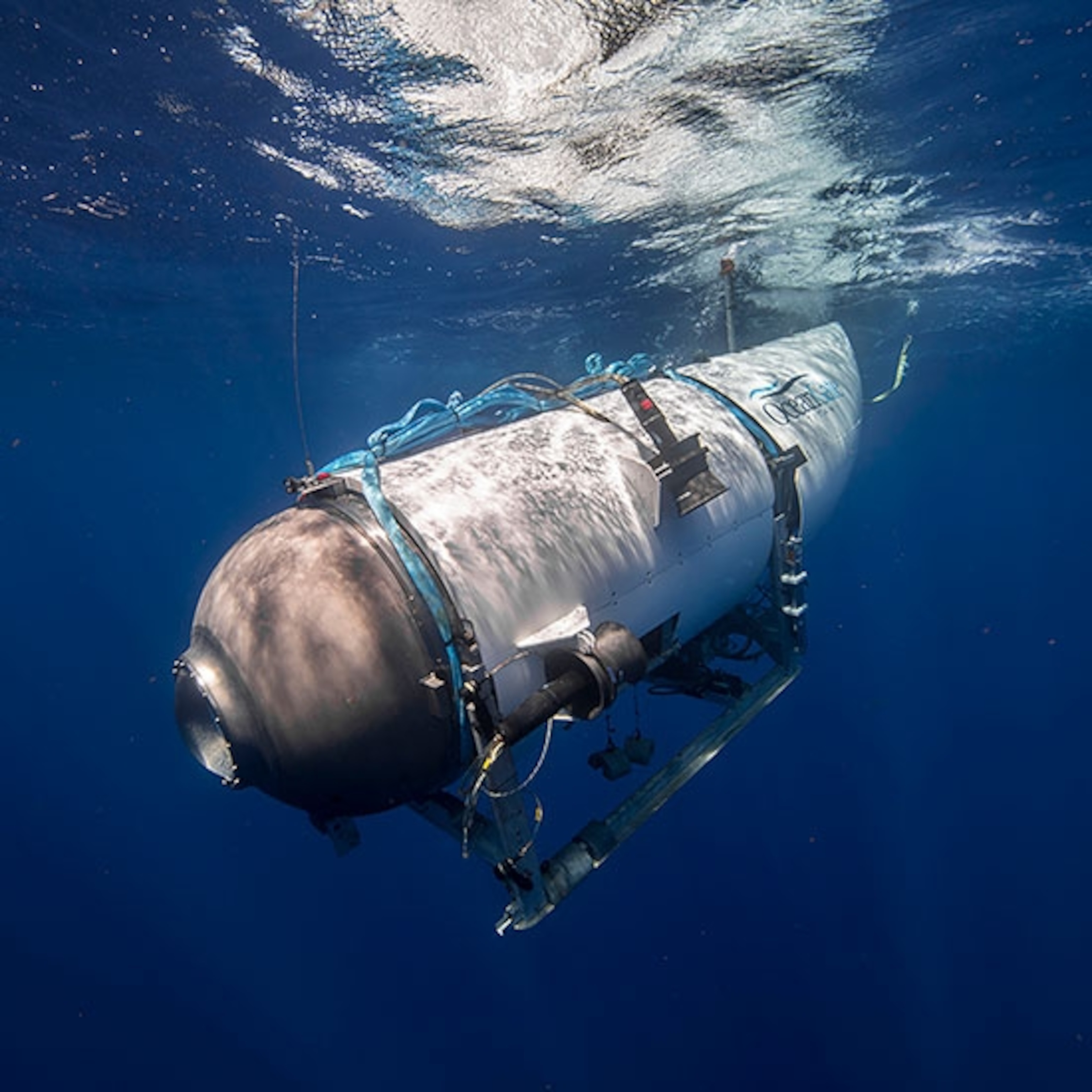

It had been five hours since my intrepid robot Gilligan left its garage on the front of the submersible Mir 1 and disappeared inside the cavernous shipwreck. Our sub was parked on the upper deck of the most famous wreck in history, surrounded by eternal blackness and over 5,000 pounds per square inch of pressure, both thanks to a two-and-a-half-mile column of water over our heads.

Safe inside the Mir, I flew the remotely operated vehicle (ROV) with gentle nudges of the joystick, its thrusters maneuvering it into the ship’s treacherous interior. The “bot” had penetrated to F Deck, paying out a thin fiber-optic cable like Theseus in the labyrinth, with only Ariadne’s twine to guide him back. Though the tiny vehicle was now seven decks below me, I felt as if my consciousness were inside the bot, its cameras my eyes, staring down the corridors of the ship. Its jeopardy was also mine, and my pulse raced with each new hazard. Turning a corner, I barely escaped being pinned by a falling “rusticle,” one of the stalactite-like formations created by the bacteria that are slowly devouring the steel of the ship.

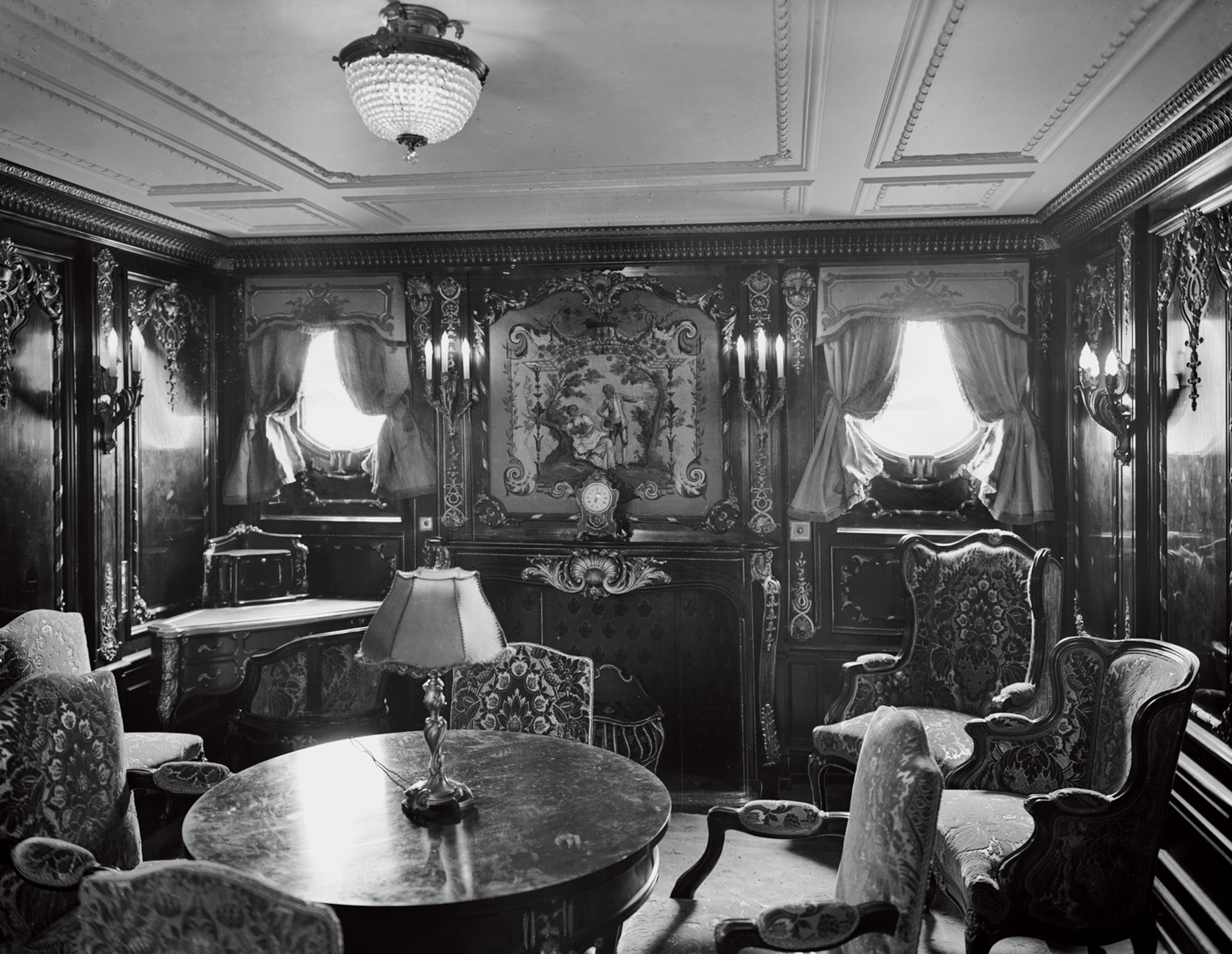

As I passed through an entrance, suddenly revealed in my lights were sparkling reflections off a wall of gleaming blue and green tiles. Teak chaise lounges lay upturned on the floor, incredibly well preserved, and above them was an arabesque dome covered in gold leaf. I had entered the elegant spa on the most luxurious ship of its time. “Tell them we’re in the Turkish baths,” I said to Mike Arbuthnot, the marine archaeologist sitting next to me. He keyed the microphone and relayed the message up to the surface.

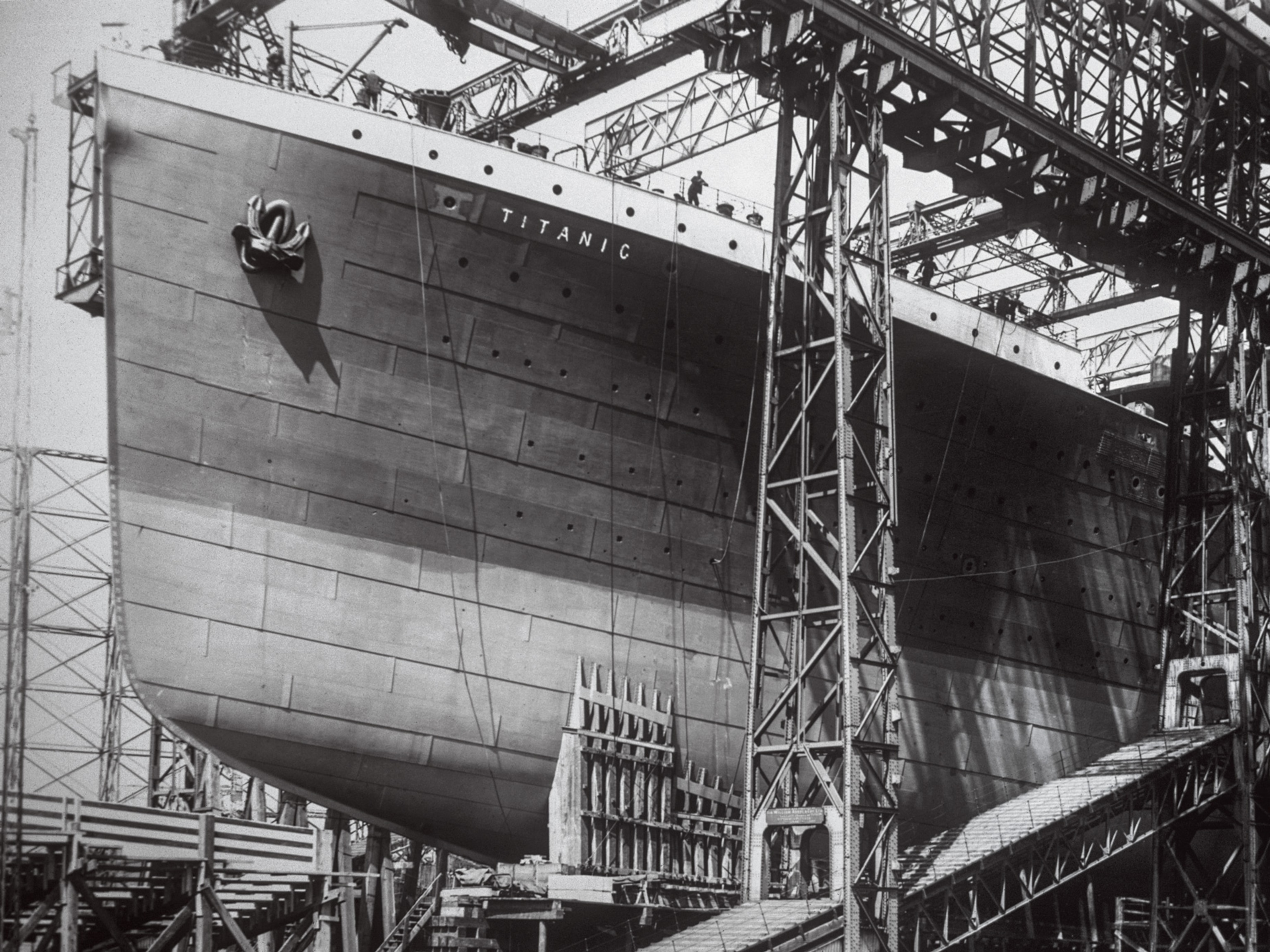

Our interior archaeological survey of the ship had begun in 1995, as I was wrapping up shooting the wreck for the movie Titanic. Back then we had an unwieldy ROV called Snoop Dog, which was little more than a movie prop, but we flew it down inside the ship’s grand staircase nevertheless, all the way down to D Deck. Its lights revealed that much of the ornate wood paneling remained intact. Snoop reached the end of its tether and could go no farther, but I could not help wondering what lay in the shadows just beyond its lights. After the movie was released, I commissioned the building of two revolutionary new robotic vehicles so we could return and truly explore the interior. In 2001 and again in 2005 I made multiple dives to the Titanic wreck and flew our bots deep inside, exhaustively surveying her interior. Ultimately we imaged and documented 65 percent of Titanic’s surviving internal spaces, including the first-class cabins, first-class reception and dining rooms, steerage cabins and open space, cargo holds, and Marconi room.

One incredible discovery followed another, in dizzying succession. In the first-class dining saloon and reception rooms, we found the tall leaded windows still intact. The hand-carved mahogany paneling on the walls and columns remains, some of it with the original white paint still visible. There are cut crystal chandeliers and, in the first-class staterooms, immaculately preserved brass beds. Filigreed iron grilles cover the yawning elevator shafts. When I first laid eyes on the intact brass call button, I felt as if I could reach out and touch it, and a ghostly elevator might still arrive. Titanic sank on her maiden voyage before her interiors could be photographed, so most of the archival images used as references for the movie’s sets were photos of her sister ship, Olympic. For the first time we were learning how Titanic herself was actually built, and the details of her decoration have now been painstakingly reconstructed from the bot videos. I now know where the movie is accurate, and where it’s not.

Of all our discoveries, the most evocative are the relics that suggest the human hands that touched them. In Henry Harper’s D Deck cabin, his bowler hat remains in the ruins of his closet, right where he left it. In Edith Russell’s cabin on A Deck, the mirror still gleams in her washstand, reflecting back the bot’s LED lights instead of Edith’s terrified face as she rushed back into the room to get her lucky toy pig before running to board a lifeboat. In another stateroom, a glass decanter and water glass sit, impossibly, still on the washstand. Had the glass been empty, it would have floated out of its holder when the room flooded, and been lost. But someone took a drink and left it half full, and there it sits today.

In the soundproof Marconi room, the wireless apparatus survives, the knife switches still in the positions left by the young operators, Harold Bride and Jonathan Phillips, revealing that they cut the power when they abandoned their post as the water rushed up the deck outside. We even imaged the transformer they had repaired just the night before the sinking. Acting against guidelines, the two young wireless geeks managed to restore the set to full power—an act that may have saved 712 lives, since without this power they might not have reached the rescue ship Carpathia with their historic SOS. Capturing these precious bot images was like touching history itself.

In 2001 I had wanted to get into the C Deck suite of Ida and Isidor Straus, the elderly couple famous for choosing to die together rather than be separated by the evacuation rule of “women and children only.” Their suite was the most ornately decorated on the ship, and in fact had been the basis for Rose’s suite, the room in which Jack Dawson draws the heroine’s portrait in my fictional narrative. I got our stalwart bot Jake as far as the purser’s office, discovering the tall purser’s safe in the process, but I couldn’t penetrate to the Straus suite next door. In 2005, determined to find a way, I wriggled the slightly smaller Gilligan through a constriction, knocking rusticles out of the way, and emerged into an open space. The bot’s lights revealed gleaming gold sparkles. Not only was the ornate mahogany fireplace still intact, but sitting on it was the gold-plated clock, just as it appeared in the archival photo, and just as we had re-created it for the movie. It was a surreal moment, fiction and reality merging in the stygian depths.

After 33 dives to the wreck, averaging 14 hours each, I have spent more time on the ship than Captain Smith himself did. In all that exploration, the strongest memories are these out-of-body experiences of ghostwalking through the corridors and stairwells of Titanic via my ROV avatar. Its gothic ruin exists now in a ghostly limbo, neither in our world nor completely gone from it. The rusticles have transformed Edwardian elegance into a phantasmagorical cavern, a surreal underworld ruled only by dream logic. But despite the sheer alienness of the place, I felt a tingling déjà vu exploring there. Having walked the faithfully built movie set for many weeks, I would turn a corner in the wreck and already know, before the bot’s video camera revealed it, what would be there. It was an eerie feeling but also strangely comforting, as if I were somehow home.