In Turkey, a power play will leave ancient towns underwater

The nation’s plan to control its most precious resource includes a controversial dam that will drown some of its history.

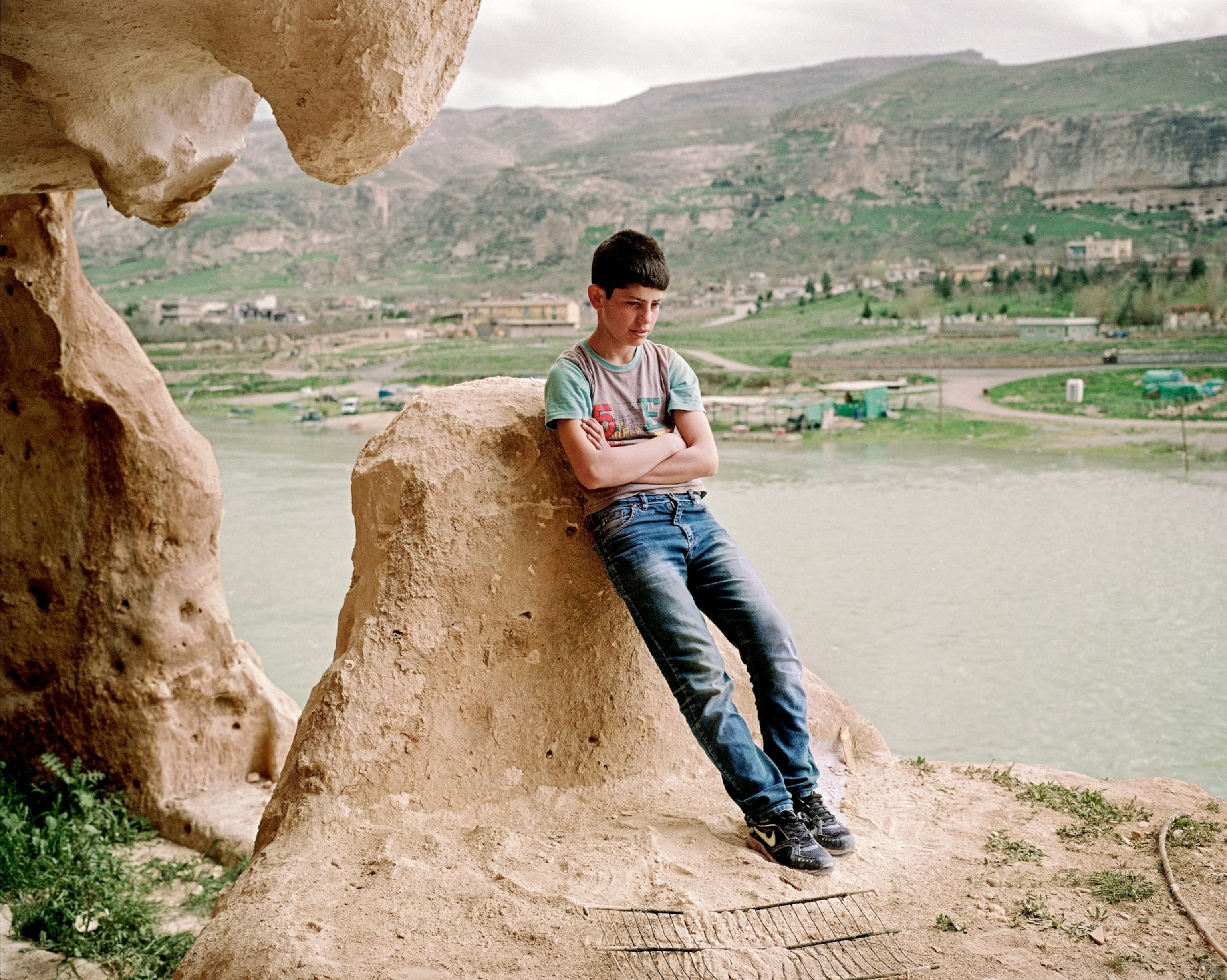

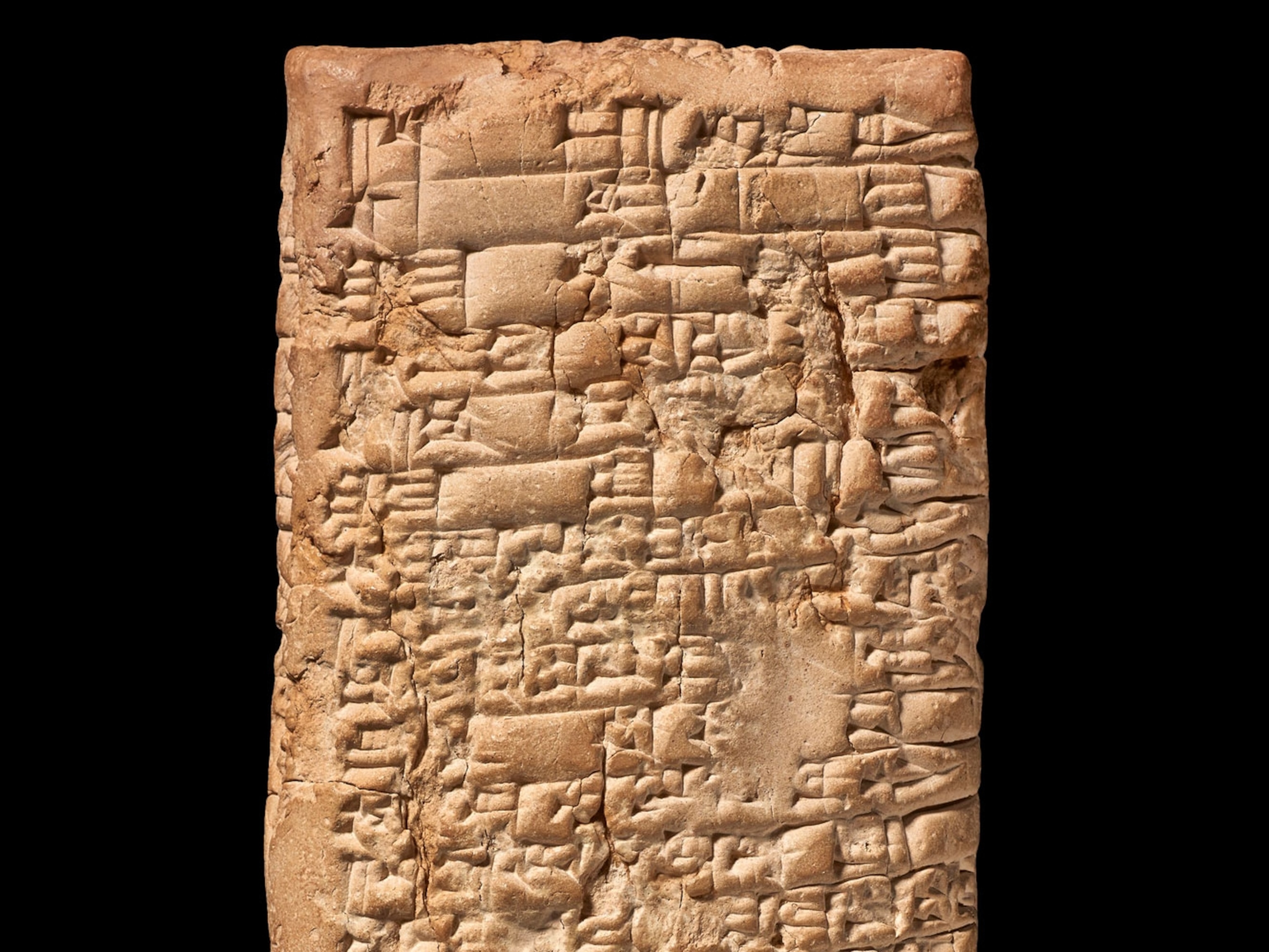

Hasankeyf is a 12,000-year-old village carved into a plateau flanking the Tigris River. It looks like something out of a surreal fairy tale. Overlooking the town are caves crafted by Neolithic pioneers and the ruins of a citadel as old as the Byzantines. The settlement bears traces of the Romans. It’s the site of significant medieval Islamic architecture, including a bridge across the Tigris that established it as an important outpost along the Silk Road. Marco Polo may have crossed there on his way to China.

Hasankeyf is also an active town in southeastern Turkey, with markets and gardens and mosques and cafés—a place with a palpable feeling of historical continuity and survival.

Yet in 2006 the Turkish government officially began work on a giant dam across the Tigris River that will lead to the drowning of an estimated 80 percent of Hasankeyf and the displacement of its 3,000 residents, as well as many other people. The dam—the Ilısu—is now almost complete, and the flooding could start anytime in the next year.

Why would a country demolish one of its most mythic places? To improve the lives of the local people through modernization, the government says. But the massive project benefits the Turkish state too. Turkey has no native oil or natural gas sources. What it does have is water.

In the early decades of the 20th century, the Turkish Republic engaged in a series of state-driven modernization projects intended to develop its economy. The southeastern region—its inhabitants relatively poor, undereducated, and minority Kurds, Arabs, and Assyrians—was largely left out. In the 1970s the government proposed a remedy: a colossal dam project that would bring reliable electricity to the southeast and irrigate the farmlands. The Turkish government would build 22 dams and 19 hydroelectric power plants across the Tigris and Euphrates river network, as well as roads, bridges, and other forms of infrastructure. The plan was dubbed the Southeastern Anatolia Project (GAP, as the acronym goes in Turkish).

The GAP soon became controversial. Syria and Iraq, downstream from Turkey, protested that Turkey could deprive them of much needed water. In 1984 the Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK), a militant separatist group—terrorists, according to Turkey and the United States—revolted against perceived injustices committed by the Turkish state, turning the southeast into a war zone. Meanwhile, European banks withdrew funding and the World Bank denied loans because of ongoing multinational disagreements, inadequate environmental assessments, and concerns about the scope of resettlement and cultural heritage protection. Even within the Turkish government, enthusiasm for the GAP as a national pride project began to fade, according to Hilal Elver, who advised the Ministry of Environment in the 1990s and is now the UN Human Rights Council’s special rapporteur on the right to food.

Indeed, by the 2000s it had become clear that the dam projects weren’t succeeding in their ostensible purpose. “They mismanaged the water, and it didn’t bring development and it didn’t bring peace,” said Elver, noting that the PKK and the government are still fighting. Today electricity generated by 13 of 19 completed dams is mostly used elsewhere. Salination, a direct result of introducing water to poorly drained salty lands, has ruined precious farms. Income from the dams hasn’t trickled down to local municipalities or people. Thousands have been displaced. Most received monetary compensation and housing but not enough to replace long-held livelihoods.

The Ilısu Dam may be one of the GAP’s most destructive projects yet. It’s set to flood not only Hasankeyf but also 250 miles of river ecosystem, 300 archaeological sites, and dozens of towns and villages. Some of the artifacts will be moved to safer ground, but the dam will displace about 15,000 people and affect tens of thousands more. Ercan Ayboğa, an environmental engineer and spokesperson for the Initiative to Keep Hasankeyf Alive, says the number might be close to 100,000. “It’s a huge project imposed on the people of the region by the Turkish government,” Ayboğa said. It “has no benefits for the local population except profits for some companies and big landowners.”

So why does the Turkish government press on? After all, other countries, including the U.S., are reconsidering the benefits and risks of dam projects and even removing some dams to restore natural water flow and river habitats. And there are less destructive ways to generate electricity, such as solar power.

Before the Deluge

Many believe that the government’s goal is simply to control this natural resource, for Turkey’s domestic needs and for its security. Case in point: When the PKK’s leader, Abdullah Öcalan, found shelter in Syria, one of Turkey’s bargaining chips to get him back was that it could shut off the country’s water supply. Water “can be used as a weapon against Iraq and Syria,” said John Crofoot, an American part-time resident and founder of Hasankeyf Matters. “It’s leverage.”

This past spring Iraq’s drought worsened, and the Tigris trickled to dangerous lows. The Iraqi government lobbied against the Turkish plan to start filling the reservoir created by the Ilısu Dam in June. The Turks acquiesced. Fatih Yıldız, the Turkish ambassador to Iraq, told critics, “We have shown once again that we can put our neighbor’s needs ahead of our own.” But for decades the government’s attitude has basically remained the same: Iraq has oil, but Turkey has water—and it can do with that what it pleases.

People in Hasankeyf protested in March, after government officials served the merchants who worked in the historic bazaar with eviction papers and told them to start moving to new commercial properties in New Hasankeyf, a series of bland, mostly uninhabited buildings on a nearby plain. The merchants argued that their businesses couldn’t be supported by a ghost town. The eviction, they said, violated their human right to work. They prevailed, if only temporarily.

In the years since the dam construction began, the people have been living in a vague, agonizing limbo, not knowing when they will have to leave their homes. The last anyone heard, the government was going to start filling the reservoir in July. That didn’t happen. So the people wait, and live. It’s as if the longer Hasankeyf is not flooded, the easier it is to believe that it never will be.

While on assignment for this story, French photographer Mathias Depardon was arrested by Turkish police and imprisoned for 32 days. He was not formally charged, and no reason was given for his eventual release. Although Depardon had lived in Turkey for five years, he was banned from the country for at least 12 months. Before the arrest, he had shot more than a hundred rolls of film—all were recovered and sent to National Geographic.

Suzy Hansen is a writer living in Istanbul. Her first book, Notes on a Foreign Country, was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize.