How these two photographers got inside the minds of animals

Jasper Doest and Paolo Verzone were among the photographers who captured the rich inner lives of animals for National Geographic’s October cover story.

We know that dogs and cats can feel happy, stressed, grumpy, or scared—and dogs can even “catch” their owners’ emotions. But what about rats that show empathy or monkeys with a strong sense of self? The team behind National Geographic’s October feature story explores how a wide array of animals exhibit complex emotions similar to ours.

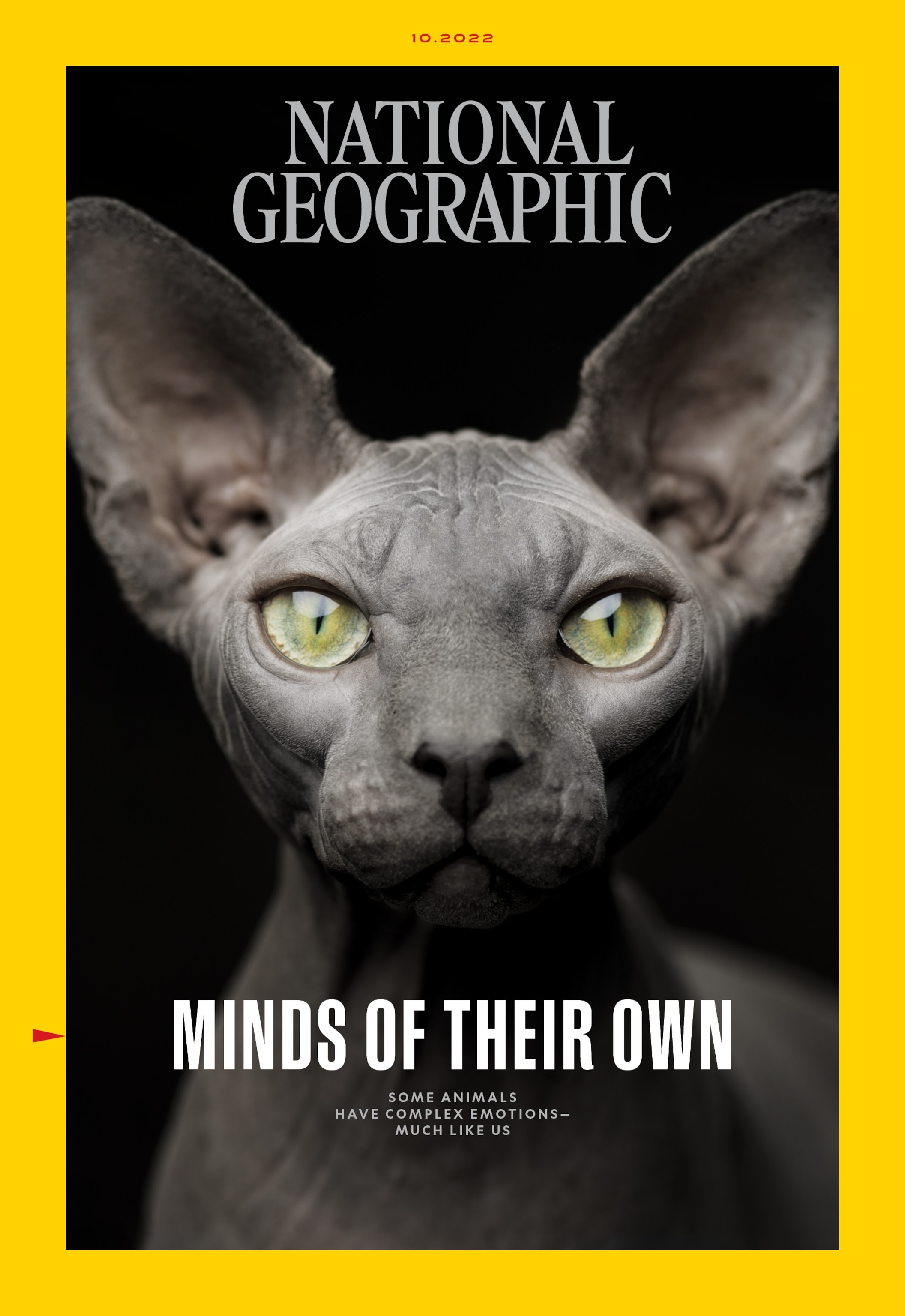

In addition to Vincent Lagrange’s cover image of a Canadian sphynx cat, National Geographic recruited several talented photographers to capture animal minds across the globe. We spoke to two of them, Jasper Doest and Paolo Verzone, for more about how they were able to photograph the “animal minds” of their subjects.

What’s the story behind the cover?

This month’s cover story explores the many ways animals are capable of displaying sophisticated emotions, such as empathy and kindness. Behavioral studies have given us a deeper understanding that animals possess not only cognitive abilities but emotional ones too.

Doest photographed the Japanese macaque staring at its reflection in the mirror, as well as the Australian shepherd getting scanned in a magnetic resonance imaging machine. He says both images presented different challenges and called for him to think on his feet.

Photographing the Australian shepherd was technically difficult because Doest couldn’t use lighting in the sterile white room where the image was taken. Doing so would potentially scare the dog and also ruin the MRI output.

“I found a way to keep my distance but still get up close and personal, so people feel like they’re still there with the dog,” he says.

For the Japanese macaque, Doest photographed the animal in a park where wild monkeys come and go as they please. Many distractions surrounded him, he says, which forced him to be patient and wait for that right opportunity, instead of running around with the monkeys.

Although each worked on their own, Doest and Verzone share similar sentiments when it comes to the impact of this story.

Doest hopes readers will look at animals differently and gain a new sense of empathy for their experience. “We’re not that different,” he says, of humans and animals. “We look different and maybe behave differently, but it doesn't mean we’re complete opposites or are more important than they are.”

WHAT'S INSIDE THE ISSUE

• What a 2,000-mile journey around Afghanistan uncovers a year after the Taliban takeover

• The Alps’ magical ice caves risk vanishing in our warming world

• Their identity was forged through resistance: Inside the lives of Brazil’s quilombos

Verzone agrees that animals can teach us so much if we pay attention to them. He was tasked with photographing a behavioral study at Tel Aviv University that studied consolation behavior in rats—specifically, if they would free a fellow rat trapped in a tube. Researchers found that the rats showed compassion for the trapped rat and freed it, but typically only if it belonged to their social group.

“I learned so much from photographing them,” Verzone says. “Their capabilities to empathize surprised me completely.”

The photo shoot came with its own set of challenges—including the smell of rat excrement in the lab—but Verzone approached it with an open mind. He allowed himself an extra hour to observe the rats and listen to the scientists discuss their work.

“This was not in my field of work. I rarely interact with animals, so it was an interesting challenge for me,” Verzone, a portrait photographer, explains. “I immediately went into this mindset of portraits … I had to understand them.”

In setting up the perfect image, Verzone also played around with the lighting, asking the scientists to let him know if the rats were showing signs of discomfort, until he felt a connection with his subject.

By the end of the shoot, the Italian photographer gained a life lesson: Empathy can come naturally for people, but others can develop their own emotional capacities by learning more about the inner lives of animals.

“Learning from them is an important thing for us,” he says. “For a better dialogue with nature, this story is the key to the future.”