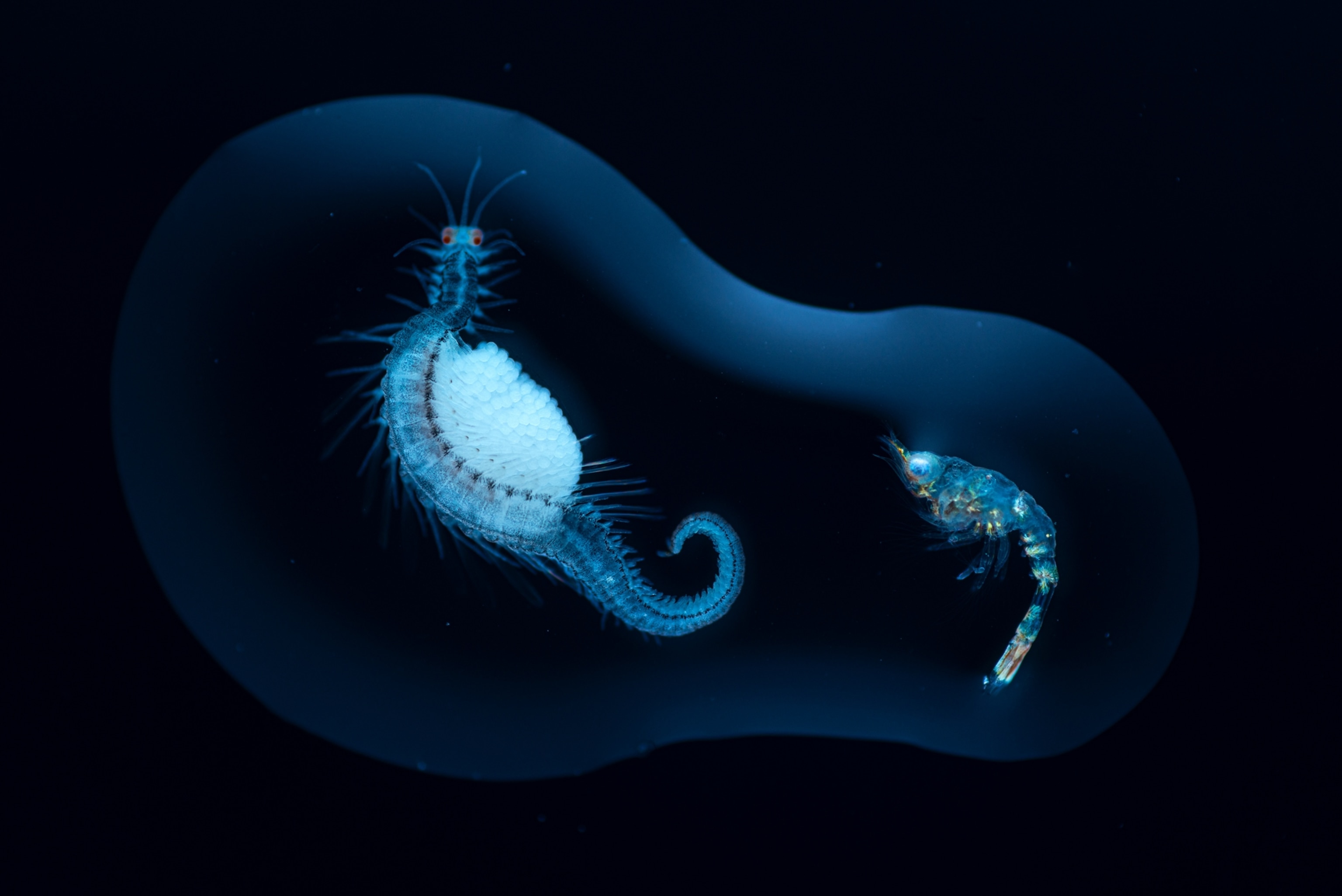

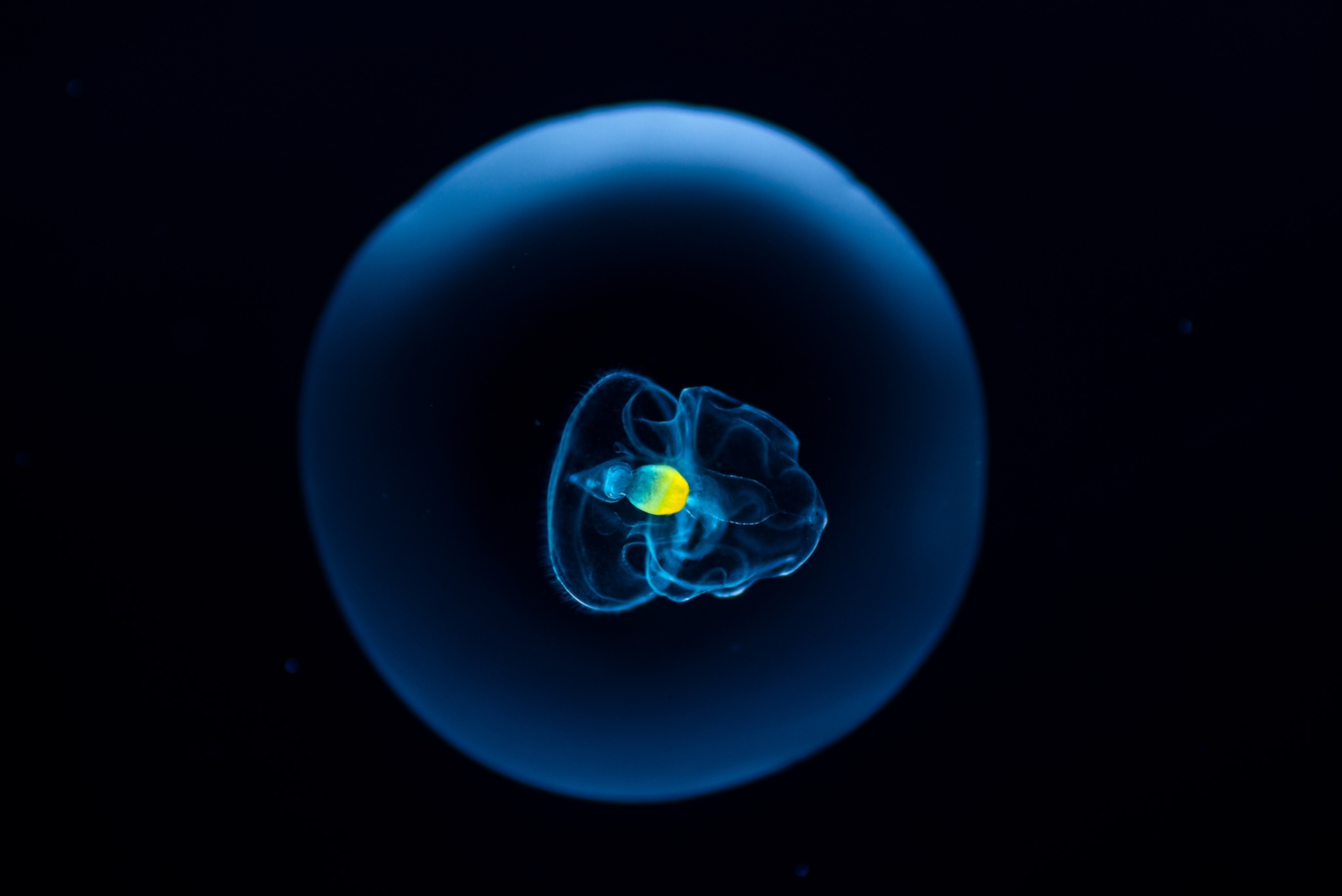

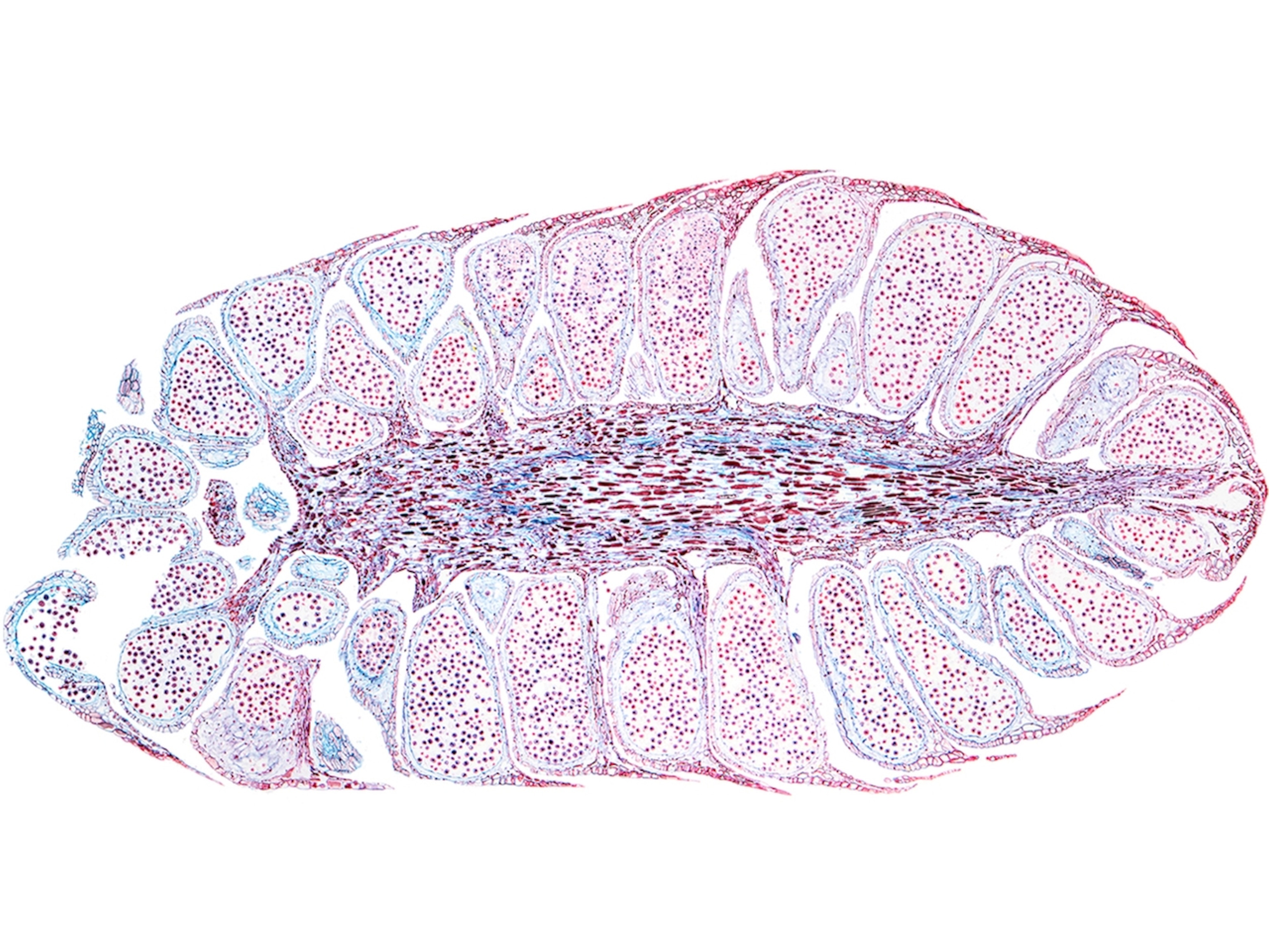

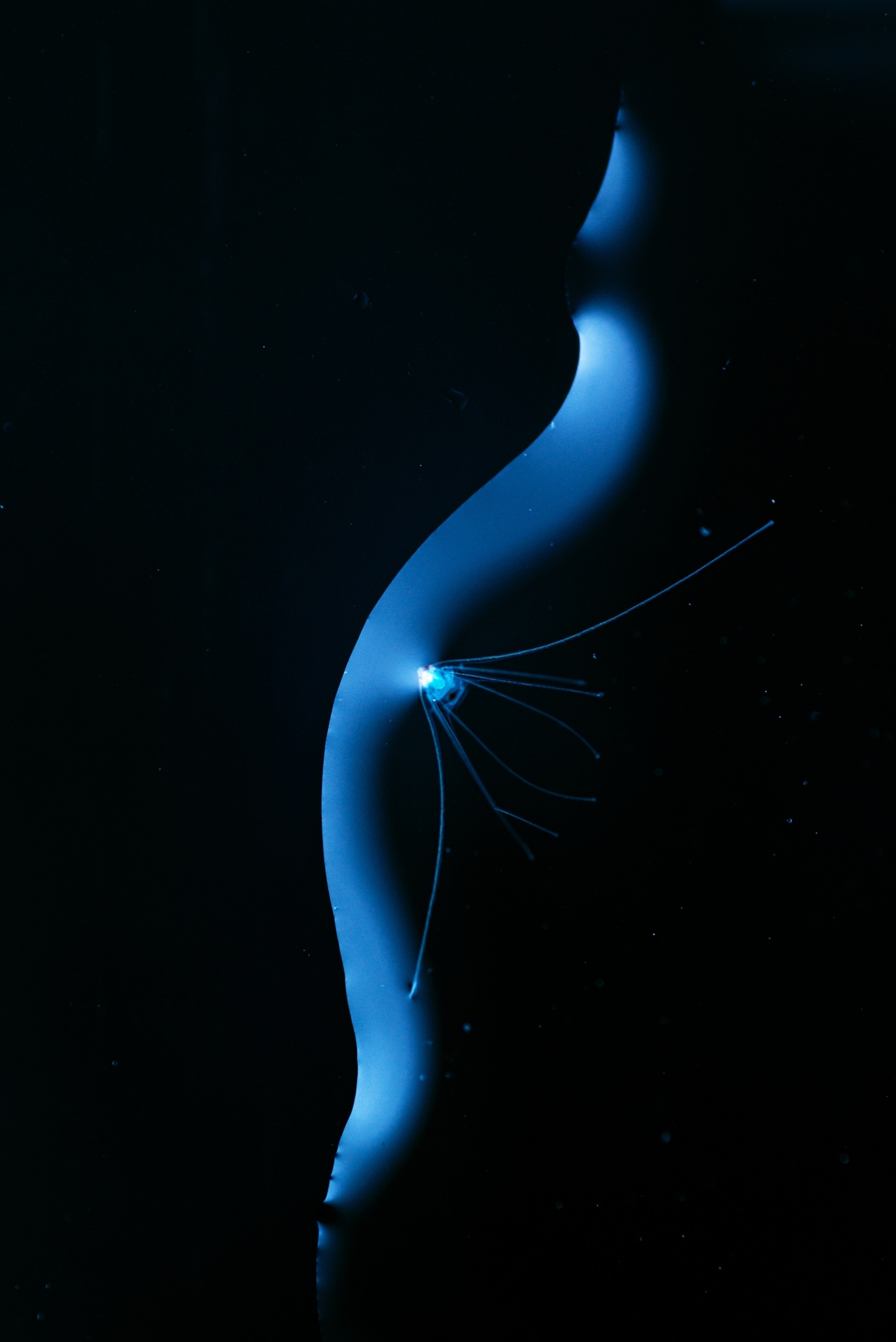

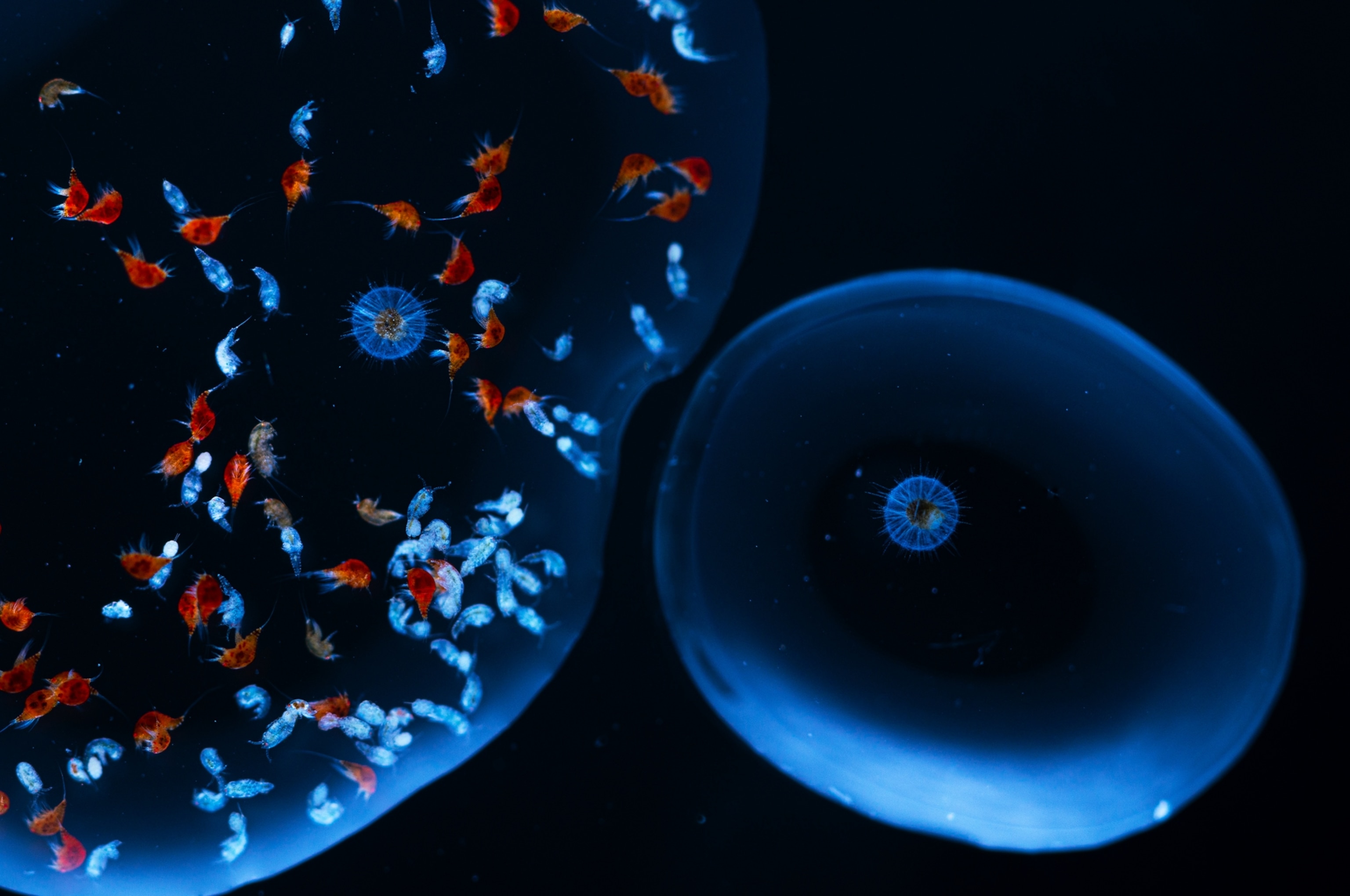

Like the vast expanses they constitute, drops of seawater teem with life. Scientists estimate that some may contain as many as a million organisms, most too small to see with the naked eye. But put a drop under a microscope, and you will likely find free-swimming fish larvae, crawling copepods, and peculiar protists. While these minuscule creatures and their water worlds are overlooked by most of us, Spanish photographer Angel Fitor has made them his muse.

As a teenager, Fitor spent much of his time peering into the fish tank at his childhood home in Alicante. “My relationship with the underwater world started actually behind the glass,” he says. Now 50 and also a self-taught naturalist, he’s turned his passion into a career. “I’m working behind the glass, only a different type of glass: a camera lens,” he says.

(See the extraordinary splendor of ordinary chemicals in these microcrystal photographs)

For the past several years, he’s been collecting water from the Mediterranean and photographing the minute critters within it—a series of images he aptly calls SeaDrops. Detecting what’s lurking in a seemingly empty bead of liquid “is always a thrill,” he says, one he likens to opening presents on Christmas morning when he was a child. “You never know what is in a sample until you place it under the lens. It feels like a genuine discovery,” he says.

Driven by what he describes as an “insane passion, curiosity, and unfathomable love for the sea,” Fitor trawls the shallows and dives the depths in search of promising specimens to take back to his studio for a closer look. “Every new sample brings new opportunities to further my appreciation of the small yet determinant creatures of our planet,” he says. Though he’s amassed hundreds of images of stunning and rarely seen microflora and fauna, his work isn’t over. To truly sate his curiosity, Fitor says, “I’d need several lifetimes.”