She designed Jackie Kennedy’s wedding gown—so why was she kept a secret?

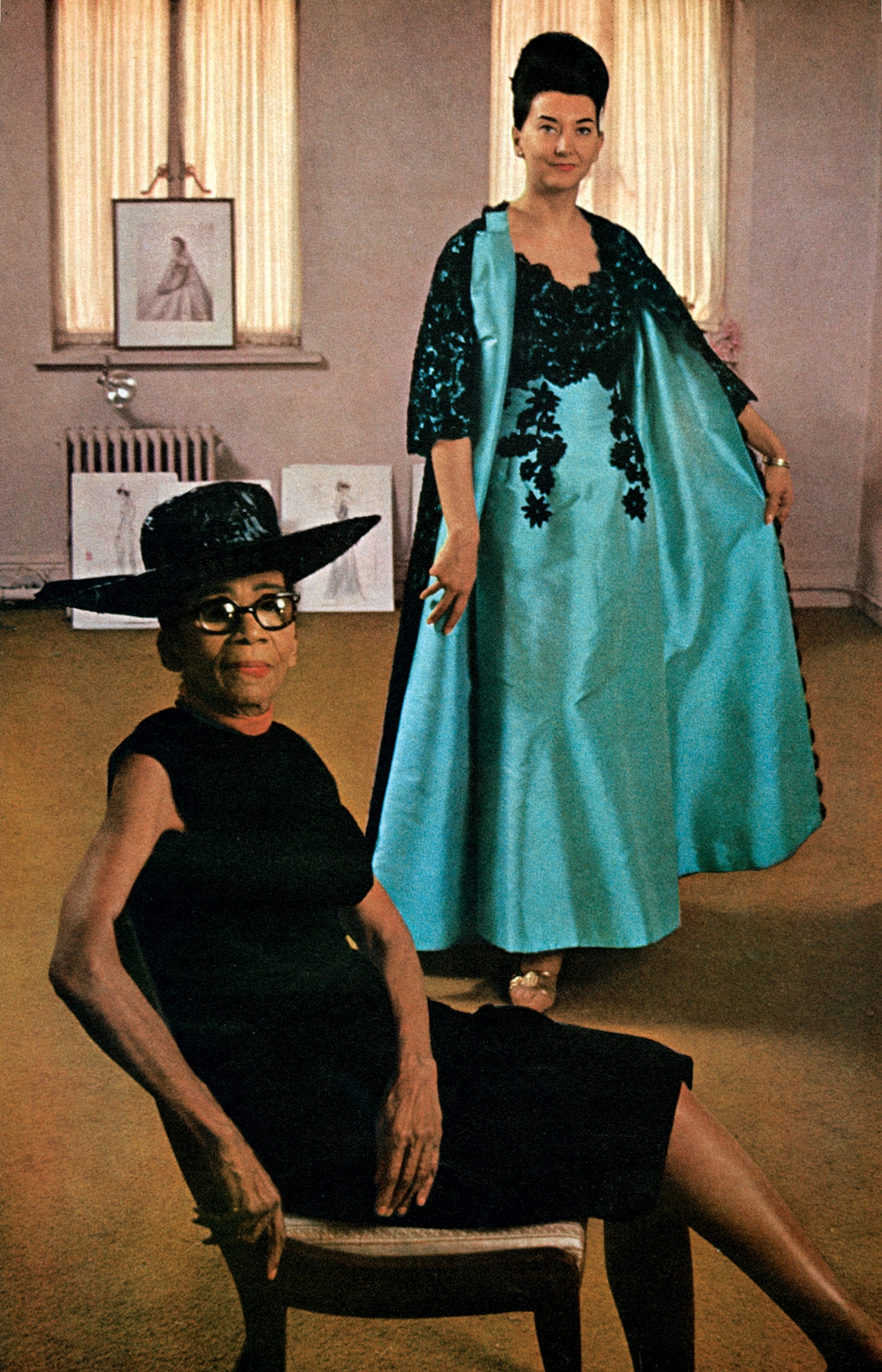

Ann Lowe was the go-to designer among the fashionable elite of the mid-20th century. But because of her race, they were loath to admit it.

The dress Jacqueline Lee Bouvier wore to wed John F. Kennedy on September 12, 1953, was an extravagant waterfall of ivory silk with hand-stitched pleats, swags, and rosettes. But who was the designer? A name was never mentioned despite a blizzard of press that noted everything from the food served at lunch (creamed chicken, petits fours) to the number of tiers on the cake (six).

Nor was it mentioned in 1961, when First Lady Jacqueline Kennedy was interviewed by Ladies Home Journal.

A Black woman dressmaker had designed it, the magazine noted, “not the haute couture.” Jackie might have preferred Paris chic—she spent a formative junior year abroad there—but her father in-law-to-be Joseph P. Kennedy was opposed to French couture for the bride of a U.S. senator on an upward political trajectory.

That dressmaker had a name. She was Ann Lowe, the equal of any French couturier.

The brush-off stung. As Judith Thurman reported in the New Yorker in 2021, Lowe wrote the first lady to tell her that she preferred to be referred to as a noted designer, writing, “which in every sense I am... Any reference to the contrary hurts me more deeply than I can perhaps make you realise.”

She was a noted designer. Period. Lowe’s clientele list was gilded with names like Roosevelt, Rockefeller, and DuPont. She created gowns for Janet Auchincloss, Jackie’s mother, and debutante dresses for Jackie and her sister Lee. Christian Dior had tea with her in Paris. Posh stores like Neiman Marcus and Henri Bendel carried her label. “A major accomplishment for any designer, let alone a Black one,” says Elaine Nichols, a curator at the National Museum of African American History and Culture.

(These are the stories behind Ruth Bader Ginsburg's iconic collars.)

“Society’s best kept secret,” the Saturday Evening Post called her. “She wasn’t a secret to the richest families in America,” says Nichols, who decries the label as demeaning. “At that time Ann Lowe was at the pinnacle of her career. They [clients] were proud to make others aware that they were wearing brands created by Christian Dior, Chanel, Balenciaga and other white designers. We can’t dismiss race as a major factor.”

Nonetheless, the label persisted and speaks to Lowe as an artist whose perseverance, courage, and passion realized her dream to create magnificent gowns, but who because of racial attitudes, social mores, and financial challenges, never won recognition rightfully hers until now.

A designer for the social elite

Ann Lowe was born around 1898 in Clayton, Alabama. Her grandmother, born enslaved, and mother, both skilled seamstresses, made gowns for socialites in Montgomery.

“Dressmaking was one of the few employment opportunities for Black women through the early 20th century,” says Elizabeth Way of the Fashion Institute of Technology and curator of Ann Lowe American Couturier, an exhibit on view at Delaware’s Winterthur Museum through January 7, 2024. “Dressmaking was safe, clean work and women could own their own business.”

Lowe sewed herself a dress when she was eight, made patterns at 10, and when her mother died in 1914, stepped in to finish four gowns ordered by the first lady of Alabama. It was, she said, “the first big test of her life.”

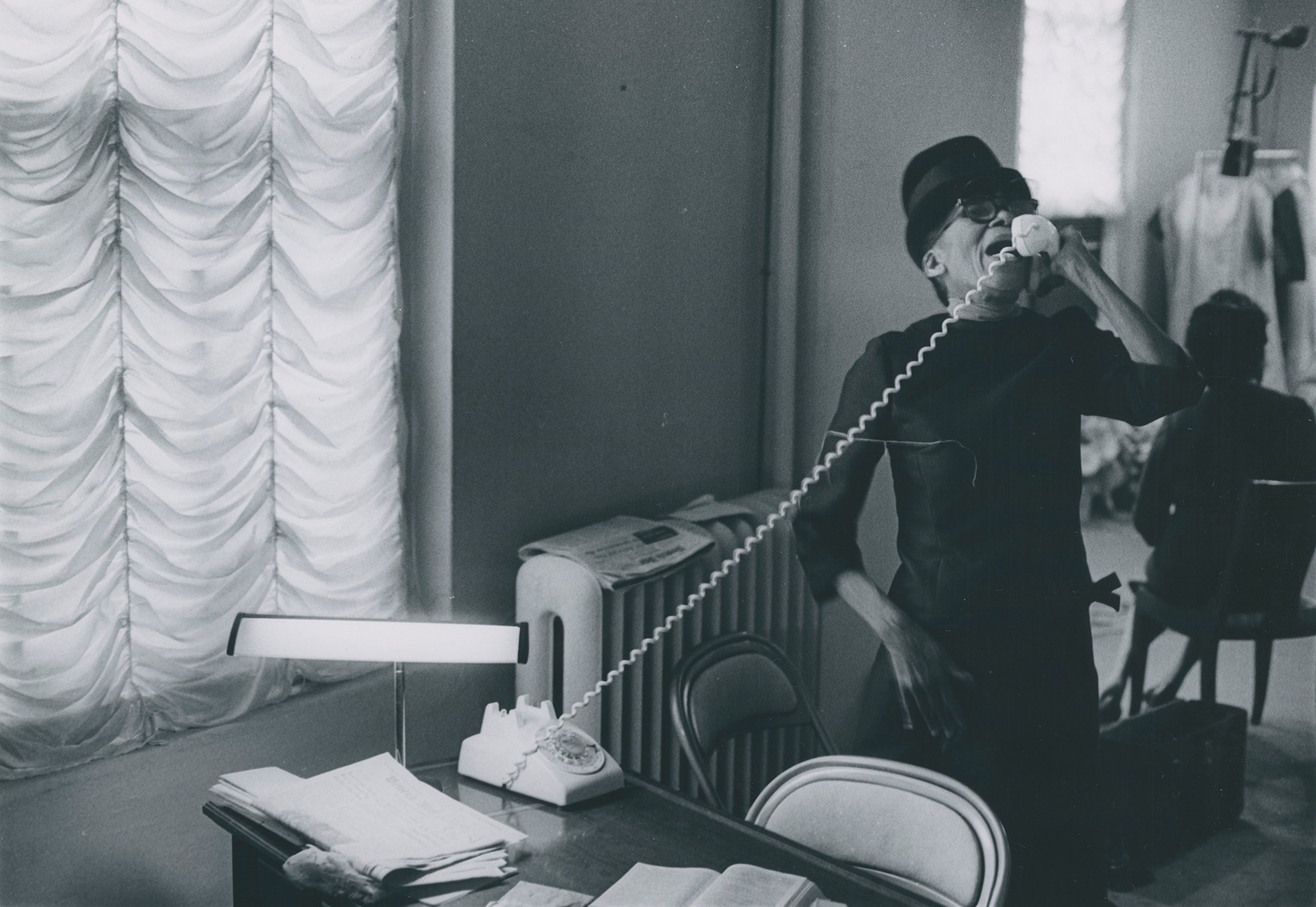

How did that make her feel? Talk show host Mike Douglas asked when she appeared on his television show in 1964. By then, she had started to get some national press and was known as the designer of Jackie’s wedding dress.

“I never gave it a thought,” she replied. “I could create anything I wanted to.

(Gender-bending fashion rewrites the rules of who wears what.)

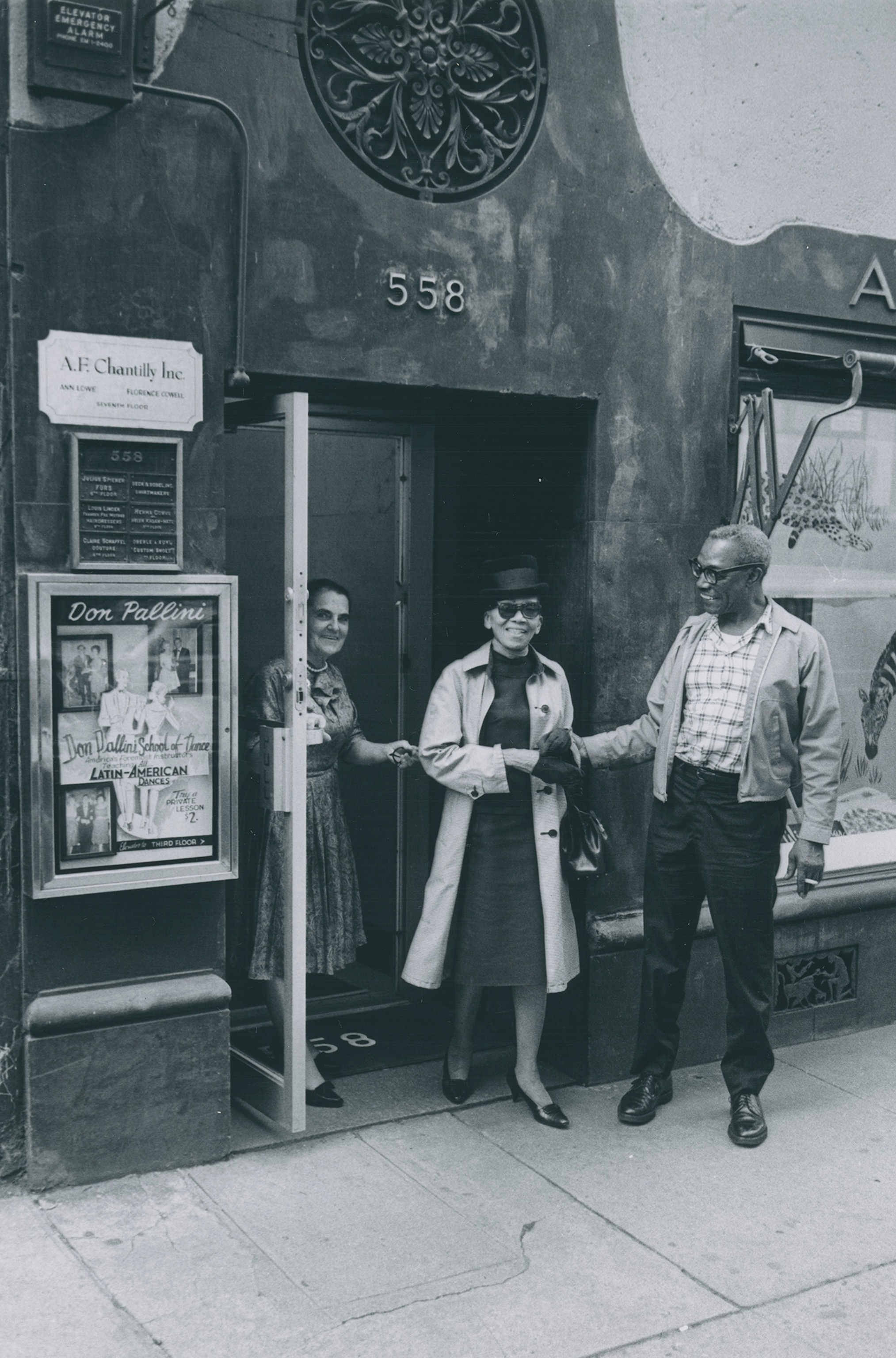

In 1928 she moved permanently to New York, where she catered to a thin layer of clientele. “I do not cater to Mary and Sue. I sew for the families of the Social Register,” she told Ebony. She was respected by, but still in service to the elite, white women she designed for, Way points out. “She knew how to interact with them on a level that deftly navigated the social and racial differences between them. In the 1920s, a Tampa newspaper ran a profile on her work as a bridal dress designer and noted that when she attended weddings to help the bride dress or tend to any last-minute issues, she wore a maid's uniform.”

Standout designs—and struggling finances

Lowe’s workmanship was exquisite. Each bead stitched on individually. Hidden details—seams bound with white lace; the small blue bow (something blue) sewn inside the petticoat of Jackie’s wedding dress. And flowers—embroidered, hand-painted, or silk roses crafted petal by petal trellising down the back of a gown.

The fit—flawless. The late Margaret Powell, a textile historian whose master’s thesis was the first scholarly appreciation of Lowe, wrote that “customers would go to Lowe’s shop the evening of their events and slip into their gowns... ‘They would dress on the spot...and sail into the night. There was never any question of fit.’”

The question was more often about solvency. Lowe cycled in and out of financial ruin. Shops opened and closed. (She was the first African American to have a couture salon on Madison Avenue.) In 1962, she owed $10,000 to creditors and $12,800 to the IRS. Friends loaned her money to pay the former. The IRS debt was paid off anonymously. Lowe thought Jackie Kennedy had stepped in.

How could you lose money making clothes for rich people? Mike Douglas had asked. “They spend a lot of money.”

No, they don’t, she replied.

Lowe lost money, among other reasons, because her socialite customers haggled over price. (“They might not do that at a French couture house,” says Way). A deal to run a boutique salon for Saks Fifth Avenue was catastrophic when it turned out she had to pay for staff and materials. “She needed a good accountant,” Nichols says. “I wish someone had provided that for her.”

The Bouvier-Kennedy wedding was another loss. Her studio flooded, ruining the bride and bridesmaids’ dresses just before the event. Lowe and her staff remade them in 10 days. She lost $2,200, but never said a word. When she arrived at the wedding with the dresses, she was told to use the servant’s entrance. She refused, threatened to take the dresses back to New York, and was finally allowed through the front door.

Creating clothes drove Lowe, not account ledgers or wealth. “When I am making clothes… I could just jump up and down with joy,” Lowe said. She loved the admiration her gowns evoked as debutantes swept into a ballroom. “Like when someone says: ‘The Ann Lowe dresses were doing all of the dancing at the cotillion last night,’” she explained.

Deteriorating eyesight and infirmity forced her retirement in 1972, but the passion for making clothes remained. “There are still a thousand ideas for dresses in my mind,” she said in the last interview before her death in 1981. “Dresses which I see in great detail.” Even when retired, in failing health, and blind, those fairytale gowns still danced in her imagination.