These balloonists disappeared when they tried to reach to the North Pole. Haunting photographs reveal their fate.

In 1897, three explorers set out to reach the North Pole by hot air balloon—but they never made it. Their disappearance became one of the great unresolved dramas of Arctic exploration.

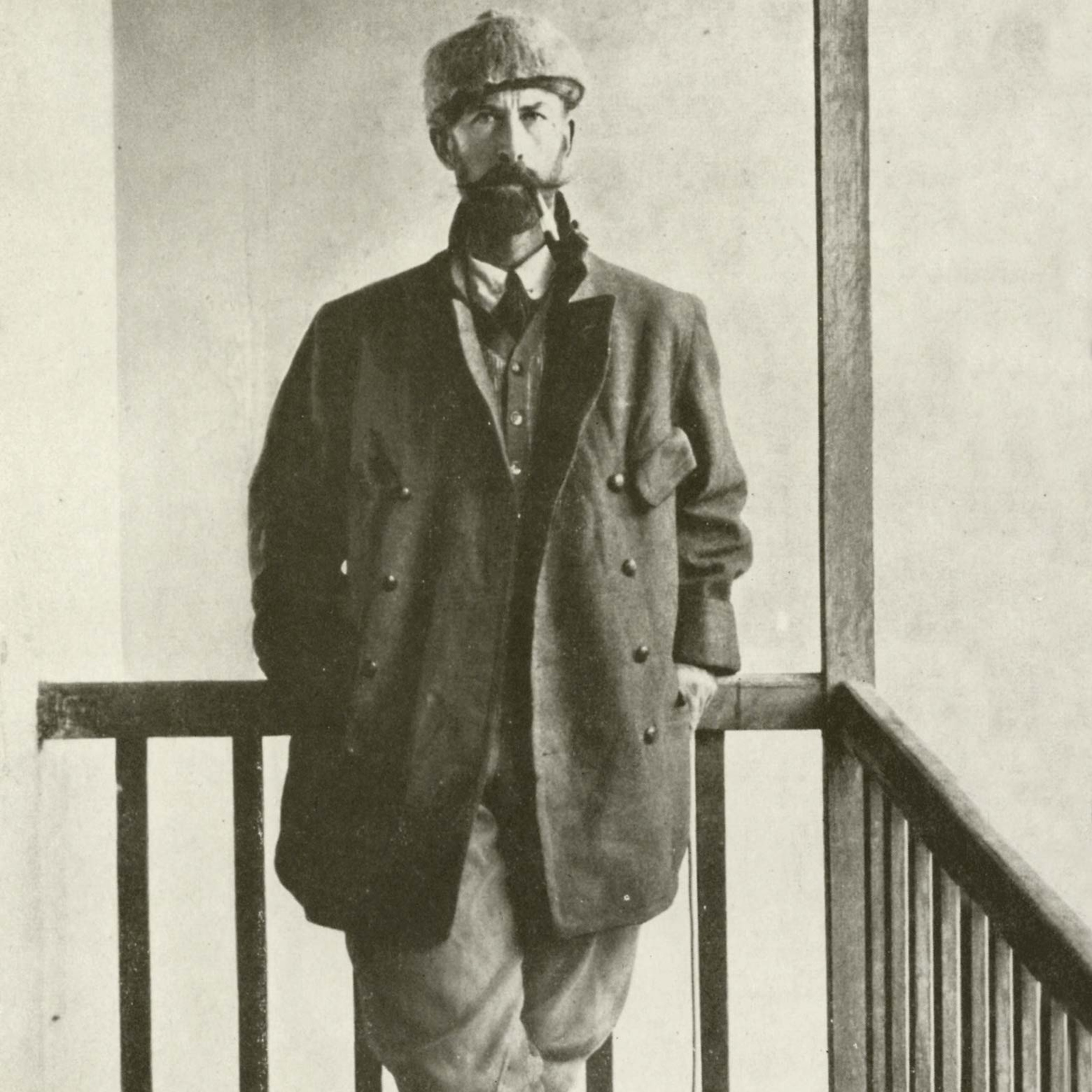

Hundreds of people tried to reach the North Pole in the 19th century, all by ship or sledge. All failed; dozens perished. But only three tried to reach the so-called Arctic Grail by balloon. They were led by Swedish engineer Salomon August Andrée, who told a London audience at the Sixth International Geographical Congress in 1895 that a hydrogen balloon could succeed where other methods had not.

Andrée’s critics heaped scorn on what the London magazine Punch called his “balloonatic” notions. There was no way to control speed and direction, they said. Failure was inevitable. Undaunted, Andrée would take off from Sweden with two fellow explorers two years later to try to reach the pole—only to disappear. Decades would pass before the world knew of their fate.

The balloon bug

Born in 1854 in the Swedish town of Gränna, Andrée grew up to be a mechanical engineer with a keen interest in aviation. In 1876, at age 22, he was wowed at the Philadelphia World’s Fair by aeronautic and balloon displays, seeding his lifelong fascination with balloon flight.

Andrée was born into a period of Arctic exploration. High-profile attempts to reach the North Pole were all the rage, yet none had been successful. In 1871 American explorer Charles Francis Hall had tried and failed to reach the North Pole aboard the ship Polaris. Undeterred by Hall’s failure, British naval officer George Nares set out for the pole in 1875, and likewise did not make it. Nares’s venture convinced many there was no way to sail to the North Pole.

Having caught the ballooning bug in Philadelphia, Andrée threw himself into flight, making several crossings of the Baltic Sea. These experiences paved the way to the conference speech he gave in London in 1895, when he made his much criticized proposal that the pole could be reached by balloon. Andrée, however, had answers for every objection. His balloon would be 100 feet tall and made of double-ply silk, varnished on both sides to prevent gas leakage, thus ensuring they could stay aloft for many days. His wickerwork “car” carried bunks for a crew of three men, three sledges, two light boats, tents, and significant provisions. He attached sails to steer, and drag ropes to control altitude. His study of winds had convinced him that a steady northerly wind would take them over the North Pole to Alaska in a matter of days.

(Arctic obsession drove explorers to seek the North Pole.)

Taking flight

Although still regarded as reckless by many, Andrée’s plan impressed Sweden’s King Oscar II. Alfred Nobel, the wealthy inventor of dynamite, provided the funding, eager for his country to make a mark in Arctic exploration. Andrée’s scheme attracted global attention. The press would be updated via buoys and carrier pigeons.

On July 11, 1897, following many frustrating delays, Andrée and his crew—Nils Strindberg, an assistant professor of physics and photographer, and Knut Fraenkel, a civil engineer—lifted off from Danes Island, Spitsbergen, in their balloon, dubbed the Örnen (Eagle).

Avoiding disaster

After briefly soaring above the crowd, something went wrong: Either a sudden cold current of air or the effect of the hanging drag ropes caused the craft to be forced downward so sharply that the car struck the water. Onlookers screamed as Andrée released ballast. The balloon climbed and was visible for about an hour, calmly soaring away to the northeast. It was the last time the three men were ever seen alive.

“Among the mysteries of the fates of several North Pole explorers, that of Andrée and his balloon expedition may be the greatest,” said P.J. Capelotti, professor of anthropology at Penn State University and author of The Greatest Show in the Arctic. “He used a novel, daring, and, as many thought, foolhardy technology all but guaranteed to appeal to the imagination.”

Over a week after the launch, one of Andrée’s carrier pigeons was intercepted with a message. Written on July 13, it stated: “82 deg. north latitude ... Good journey eastwards, 10 deg. south. All goes well on board. This is third pigeon post.” No other messages, however, were found.

“Where is Andrée? is the question being asked the civilized world over,” declared the Galveston Daily News on August 6. Years would pass before two buoys were found, both dropped on the day of the launch. One read: “We are now in over the ice which is much broken up in all directions. Weather magnificent. In best of humors.” Expeditions were sent to find the three men, but no trace of them or the balloon was found. The mission was lost.

(The untold story of the boldest polar expedition of modern times.)

Unexpected recovery

More than three decades later, the mystery would be solved. In August 1930 a team of Norwegian scientists were studying glaciers aboard a seal-hunting vessel. They took advantage of the unusually warm summer to land on White Island.

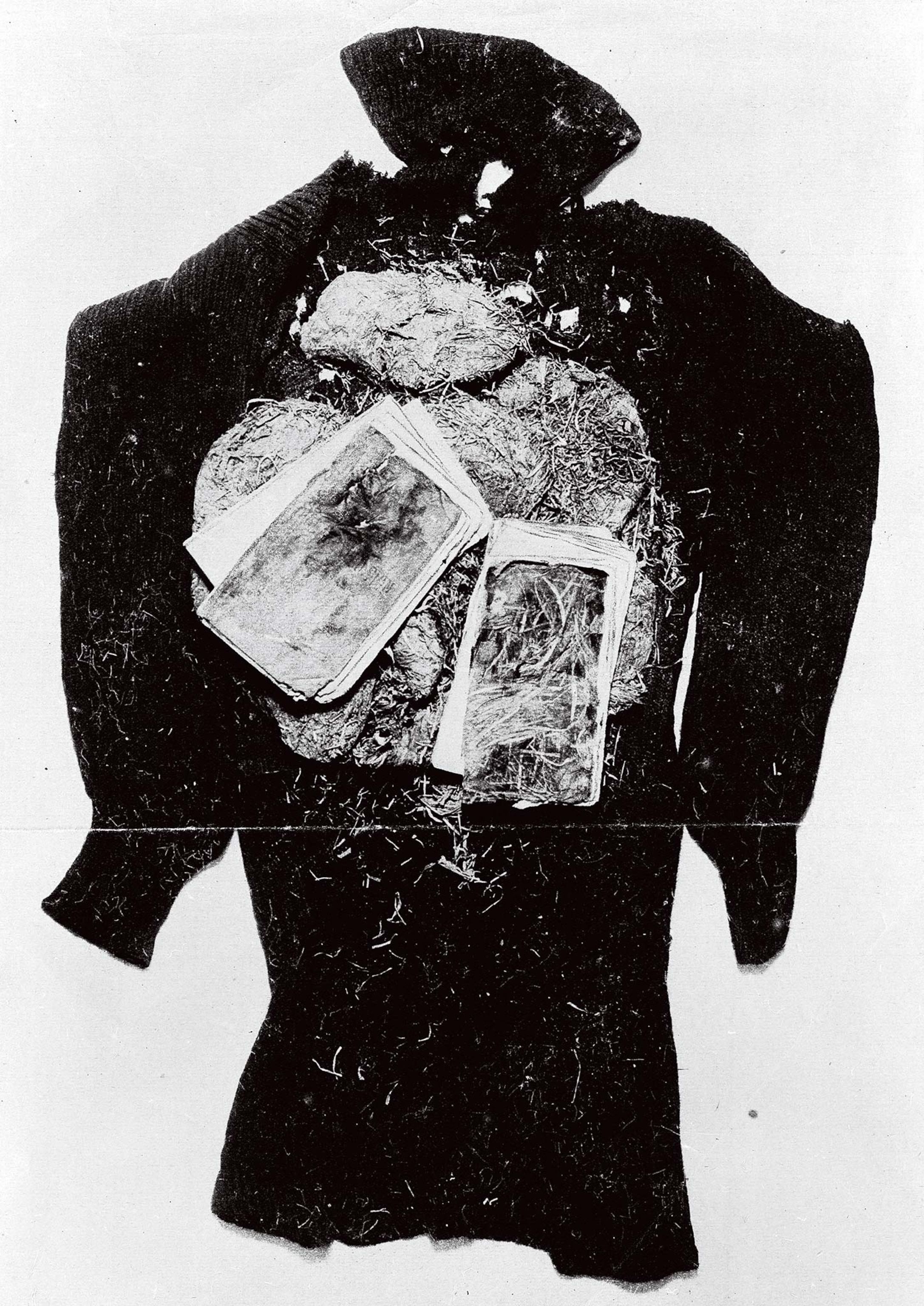

Exploring the island, they were surprised to find the remains of a boat sticking out of the ice. In it was a hook with the words “Andrée’s Pol. Exp. 1896” stamped on it. More than three decades had passed, but the fate of the Andrée expedition was finally known.

After further exploration, the remains of Andrée, Strindberg, and Fraenkel were recovered, as were their diaries, logbooks, camera, and film. The three men’s bodies were transported back to the Swedish capital, Stockholm, where they were cremated and buried.

The diaries and photographs clarified much of what had befallen the crew after takeoff in July 1897. The Örnen had remained airborne for nearly three days as it drifted northeast. Andrée’s sense of wonder is apparent from his journal entries:

Is it not a little strange to be floating here above the Polar Sea? To be the first that have floated here in a balloon ... We think we can well face death, having done what we have done. Isn’t it all, perhaps, the expression of an extremely strong sense of individuality which cannot bear the thought of living and dying like a man in the ranks, forgotten by coming generations?

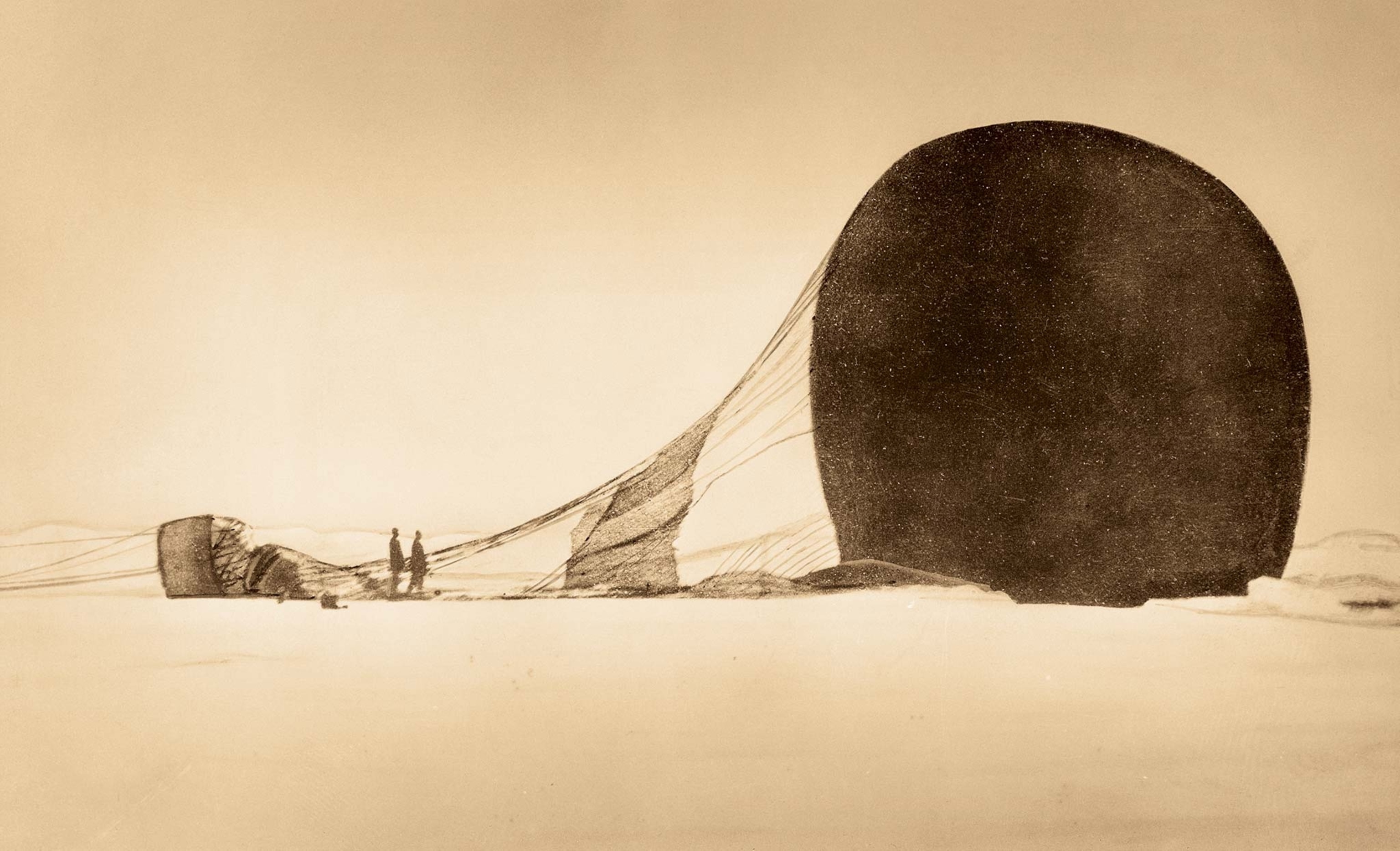

While this entry was being written, the mission was already running into trouble. Shifting winds pushed the craft westward from July 12. Hydrogen gas was leaking from the balloon, which was hovering at low altitude. Fog caused a layer of thick ice to form on the balloon’s surface, weighing it down. To stay aloft, they threw out ballast and some equipment, but to no avail. For long stretches, the balloon bounced along the ground “about every 50 meters.” On July 14 the team decided to jump ship and abandon the mission, 300 miles away from the pole.

Photographs developed from Strindberg’s frozen film reveal the remains of the crashed balloon and the camp the men set up near the crash site. Just over a week after the crash, the team decided to try to reach Franz Josef Land, an archipelago in Russia, where they had stashed emergency supplies. After they moved equipment across drifting ice for days, the ice started to drift west. “This is not encouraging,” Andrée wrote.

The three continued trying to move toward safety, but by mid-September, with dropping temperatures, they had no choice but to hunker down. They built a shelter from ice blocks and hunted seals and polar bears. In early October shifting ice forced them to White Island. On October 8, as bad weather closed in, Andrée made his last entry.

The causes of the men’s deaths are still unknown. Experts believe the trio had enough supplies to have survived the winter but were struck by illness. Researchers at Sweden’s Karolinska Institute, together with Andrée historian Bea Uusma, are applying the latest technology to decipher Andrée’s last diary, much of which is illegible. “We are finding clues that look promising, but there is still work to be done,” Uusma said.

(This Arctic murder mystery remains unsolved after 150 years.)