Can the iconic Georgia peach keep growing in a warming South?

Shorter, milder winters are threatening the state's most celebrated fruit. Scientists and farmers have a plan to adapt.

In Georgia, the peach is iconic: It’s on license plates, lottery tickets, beer cans, “I voted” stickers, and billboards.

And in the Peach State, Fort Valley is the peach capital and the site of Peach County’s annual festival, offering food trucks, beauty queens, games, live music, and large crates of ripe fruit. But the peach cobbler—baking in an 11- by five-foot pan—is the main event.

To make it, “you have to be more than a chef. You have to be an engineer,” says this year’s head chef-engineer, Rich Bennett. The massive dessert requires a custom-built oven, and Bennett says it goes in at 3 a.m. and cooks until about two in the afternoon.

Few places have the generational love of a single crop that Georgia has for the peach. It’s a love that’s motivating farmers and scientists alike to make sure the Georgia peach never dies, since peach trees require cold weather to produce fruit and climate change is warming winter weather in the southeastern United States.

But could climate change ever spell the end of the Georgia peach industry?

“We’re talking probably the second half of this century. Certainly by 2100 it could be a possibility,” says Pam Knox, an agricultural climatologist at the University of Georgia.

Georgia peaches need to chill

The entire southeastern U.S. is warming, and the average winter temperature in Georgia has risen by five degrees Fahrenheit since 1960. That warming trend is expected to continue, and peach trees need a minimum number of chilly hours for their spring buds to bear fruit.

Every winter, when temperatures fall below 45°F, peach trees produce the hormones that tell them to go dormant. The average Georgia peach needs anywhere from 650 to 850 hours of cold weather in a season—so-called chill hours. One of the most popular varieties, the Elberta peach, needs at least 800 hours of cold weather. It’s a trait peach trees evolved to withstand cold winters in their native China. By going dormant, the tree version of going to sleep, they reserve energy and ride out unfavorable growing conditions, awakening after they’ve properly rested.

“When they go into dormancy, nothing can wake them up until the cold requirement is satisfied,” says Ksenija Gasic, a horticulturist at Clemson University in South Carolina.

Once a peach has enough chill hours, temperatures above 45°F begin to shake the trees out of dormancy like a seasonal alarm clock announcing that it’s time to start making peaches. If exposed to enough warm weather, the tree’s flowers start to develop and open. Some may even produce small fruitlets. But the tree needs to stay on that warming trajectory; when a spring frost hits, as it often does in Georgia, it can damage fruit that’s already growing.

“We already have a little fruit that is full of water,” Gasic says of peaches that bloom early. Then when a frost comes, “That water freezes and splits the cells, and there goes your fruit.”

In 2017, an especially warm winter destroyed 85 percent of the state’s peach crop, since the peaches didn’t get enough chill hours to facilitate blooming. Between 1980 and 2010, central Georgia saw about 1,100 chill hours on average every year. In 2016, they averaged just about 600 chill hours. In 2017, farms struggled to reach 400.

“It was so bad we thought they were not going to come out of dormancy. We didn't care about the blooms anymore; we wondered if the plants would survive,” says Dario Chavez, the horticulturist overseeing peach research in the University of Georgia’s fields, greenhouses, and labs.

After that winter, Lauren Parker, an agricultural climatologist at the University of California Davis and a native Georgian, decided to investigate. “The question was whether or not those warm winter temperatures would have been possible in the absence of climate change,” says Parker.

In a study published in 2019, Parker showed that 2017 likely would have been a warm year even without global warming. But, “we also showed the effect of climate change exacerbated those warm conditions,” she says, and made them more likely.

That presents a challenging future for southern-grown peaches, fruit that needs a delicate balance of cold winter weather and temperate springs to grow successfully.

Creating a more temperature-tolerant peach, says Gasic, is complex. Peaches can grow in Florida, after all, needing as few as 50 chill hours or none at all. But in Georgia, peaches must contend with a pretty reliable frost during the spring.

“That is one of the mysteries of climate change in Georgia,” says Knox. “Even though we’re having warmer temperatures over the winter, the date of the last frost has not changed that much.”

Farmers take notice

At Lane Southern Orchards, the largest peach farm in Georgia, 5,000 acres in and around Fort Valley produce over a million cartons of peaches every year.

The combination of fewer chill hours and steadfast late spring freezes poses a conundrum for farmers: plant a peach tree that needs only a couple hundred hours below 45°F and your fruit will bloom earlier, exposing itself to frost damage. Plant a frost-resilient peach tree that blooms after the frost, and you risk the perils of the tree not emerging from dormancy because of a too-warm winter with too few chill hours.

“You try to fix one problem, and you end up with another one,” says Robert Dickey, a third- generation peach farmer and Georgia state senator. At Dickey Farms, founded just outside of Fort Valley in 1897, Dickey says he’s hopeful they’ll one day have new, more consistent varieties or that the warmer winters they’ve experienced are just part of a natural cycle.

Looking for solutions

An ideal peach would need just 500 to 700 chill hours but require more hot-weather days to bloom, says Clemson’s Gasic.

“They get their chilling, but they sit and wait [for warm weather],” before bearing fruit, she says of an ideal climate-resilient peach.

Gasic and others are researching peach DNA, trying to determine if the gene that counts chill hours might be different from the one that detects warm days. Such a genetic difference could result in a new “medium-chill” peach that could tolerate South Carolina and Georgia’s spring frosts.

In the South, researchers are looking for other, faster fixes, already cross-breeding peaches for climate resilience, diseases, pest resistance, drought tolerance, and taste. Making a new variety can take anywhere from seven years if you’re lucky to 14 if you’re not, says the University of Georgia’s Chavez.

“I have this crazy idea that I can produce a low-chill variety in Georgia,” Chavez says. He wants to breed a peach that can still thrive in warmer winters, needing just 350 to 500 chill hours, and a technical solution to help them withstand spring frost, could be one that still makes Georgia the Peach State a hundred years from now.

In his work with Georgia peach farmers, Chavez uses examples of warming farther south to make his points, to a group cautiously adapting to a shifting climate.

“I just work with facts,” says Chavez. “I tell them I think the issues Florida is having, we are going to have, and we should be thinking about how we’re going to deal with it.”

Chavez collaborates with scientists at the University of Florida and grows experimental peach varieties near the Florida border. He expects the loss of cold periods in those regions to slowly creep north, as the northern and southern borders of the tropics expand toward the Earth’s poles.

A glimpse of the future lies farther south

More dramatic warming is something southern Georgia peach farms are already seeing.

At the Lawson Peach Shed, not far from the Florida border, the owners have been growing peaches for over a century, says Barbara Lawson. “We grew 600 acres, but now we’re down to 100.”

They stopped shipping, closed their large fruit-packing facility, and now focus only on their popular highway farm stand, which sells peach-flavored products including ice cream, cobbler, and sweet tea.

“The weather is not like it used to be. It used to be we had pipe-busting weather,” she says of winters she experienced as a kid. “Now we can wear shorts” in winter.

Half a century ago, peaches the Lawsons grew needed 900 chill hours. Today they grow a low-chill variety bred for warmer winters that need around 350 to 450 hours of cold weather. The fruit’s flesh is redder than what Lawson calls a “classic peach,” but it tastes just as sweet.

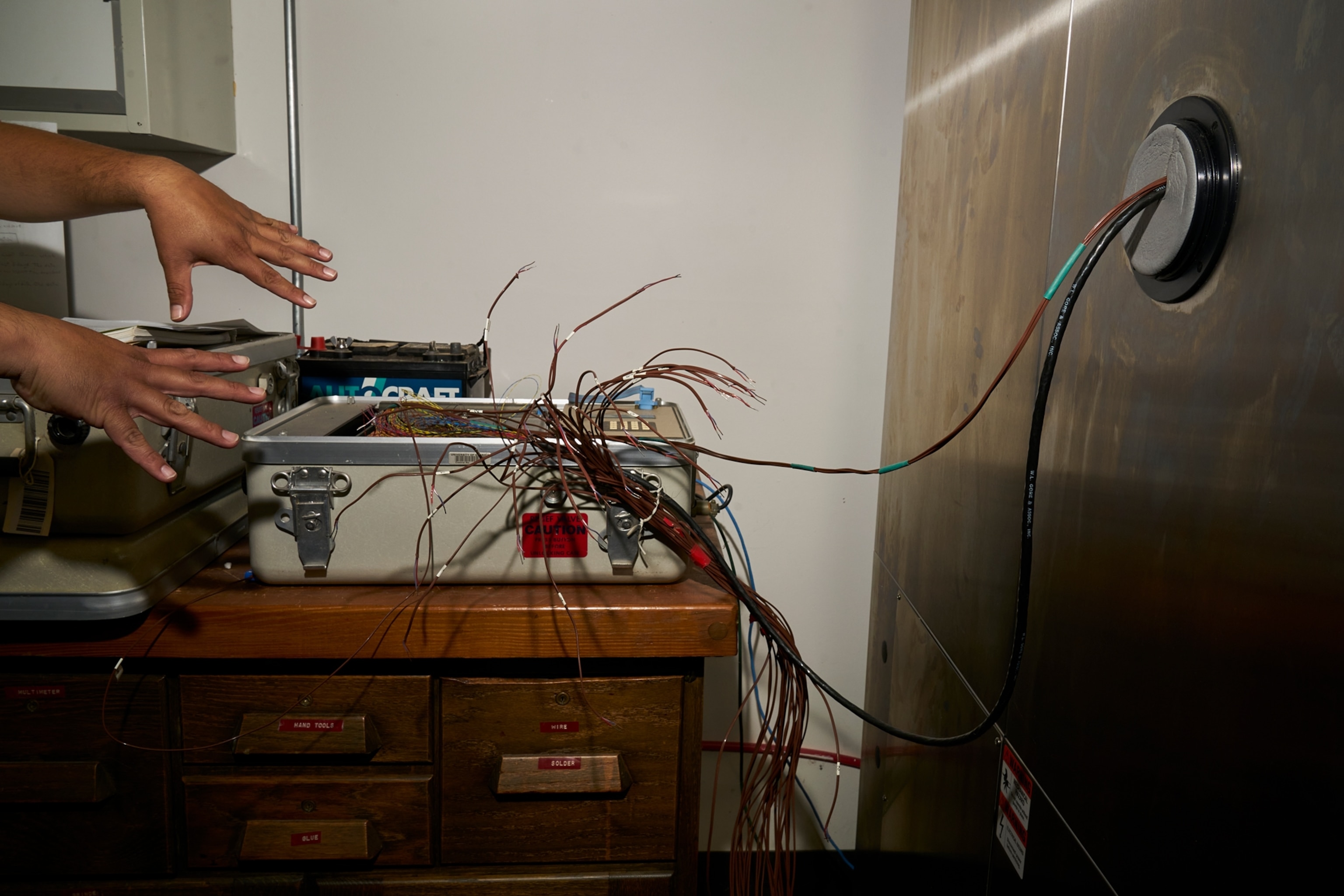

In addition to more resilient varieties, there are technical fixes that could help peaches. Chavez is experimenting with a goopy, cellulose-based mixture that looks like a pulpy mayonnaise and has potential to help insulate trees from cold weather. Because it’s made of cellulose and water, the solution can be sprayed onto peach trees a few days before temperatures drop without introducing a new chemical contaminant like a pesticide. Large wind machines would help stave off the spring frost by pulling warmer air closer to the ground.

But deploying these solutions on a large scale will be a challenge. Wind machines are expensive, says Chavez, and the cellulose spray is still in the research stage, though similar trials on cherries and apples at Washington State University have shown promise.

What is Georgia’s agricultural future?

Chill hours aren’t the only growing condition in flux. A changing climate means that the Southeast likely will see swings in precipitation. Farmers who once didn’t need to irrigate their trees may be more likely to see periods of drought punctuated by short bursts of intense rainfall. More humidity, which Knox says the state is already seeing, could also foster disease and fungal infections.

But Georgia will always remain an agricultural hub, says Knox. The soil is fertile and rainfall—at least for now—is more reliable than in states like California. As the West experiences harsher droughts, heat waves, and wildfires, maybe agricultural production will shift to Georgia, she says.

“One of the interesting things happening is we’re starting to see new crops come into Georgia,” says Knox. “I’m working with folks now looking at citrus, especially the cold-hardy varieties like satsumas. We’re also growing olives in Georgia, which we couldn’t do before.”

Relative to the rest of the country, Georgia has been warming at a slower rate, but that reprieve could be ending.

“The Southeast has been in something called a warming hole,” says Knox. Scientists have found evidence that this warming hole over the region—where warming temperatures have been less prevalent—has resulted from trees that grew back after the post-Civil War South turned away from cotton production, as well as the sunlight-blocking effect of aerosol pollution.

But that effect may be waning. Scientists at Dartmouth College authored a 2018 study on the warming hole, and say there’s now early evidence suggesting the anomaly may be “overrun” by climate change.

Just how much the Southeast will warm in the coming decades depends on how many more warming greenhouse gases are pumped into the atmosphere, says Knox.

“The timeline for increasing temperatures is a very tough thing to say because it depends a lot on human behavior,” says Knox—whether high carbon-emitting countries will take the necessary quick measures to reduce their use of fossil fuels, which drives climate change. It likely won’t be farmers today facing existential questions about the Georgia peach, but it could be their grandkids, she says.

For now, farmers and scientists are confident they can adapt, developing new peach varieties and techniques for growing them that help Georgia’s icon live on.

More than a fruit

When the festival’s peach cobbler is ready to serve, a royal court flanks the oven—the young pageant contestants—from four to 23—who days before competed for peach titles. This year’s Miss Georgia Peach is 19-year-old Sydney Dorsey, who tastes the cobbler first.

Her new crown sparkling, Dorsey takes a bite, nodding her head in approval, and the crowd of eager festival-goers claps and chants “scoop!”

Bennett and his sous chefs scoop up cobbler for a line of people that stretches three blocks. The diehards carry enormous Tupperware containers to fill with cobbler and freeze.

With temperatures in the 90s, the cobbler enthusiasts find walls and trucks to lean on while they eat even hotter bites of the dessert. It’s sweet and buttery, and the bits of peach and cobbler biscuit have been simmering for so long it tastes like a syrupy sweet porridge, deliciously and indulgently peachy.

Festival Chair Tisa Horton is exhausted by the nonstop questions from festival goers: When does the peach eating contest start? What time is the concert? Where can I find a folding chair? But she’s content.

“I love the hometown feel of it,” she says, fanning herself with a folded piece of paper. “We have the best sweet Georgia peaches.”

A longtime resident of Peach County, Horton grew up with peaches as a way of life that revolved around the harvest of a small, fuzzy fruit.

“As young teenagers we worked in the peach fields,” she says. “It’s part of our story. It’s our history.”