This Persian marvel was lost for millennia

Only one ancient account mentions the existence of Xerxes Canal, long thought to be a tall tale. But archaeology is confirming that Persia's engineering triumph was real.

Historians had long believed the Xerxes Canal was a myth, but they never stopped searching for it. For millennia the only evidence of this engineering feat was found primarily in one written source, leading many scholars to scoff at the existence of a canal built so that the mighty navy of Persia could pass through it in 480 B.C.

Recent archaeological finds on the Mount Athos Peninsula in modern-day Greece suggest the engineering marvel did indeed exist. Its creation is a vivid reminder of ancient Persia’s wealth, strength, and inventiveness, which Athens and other city-states faced when this mighty foe invaded their lands.

(History's first superpower sprang from ancient Iran.)

Peril at sea

The story of the canal takes place during the Greco-Persian wars of the fifth century B.C. Many battles, such as those at Marathon and Salamis, have become famous underdog tales in which the Greeks challenge a much more powerful Persian foe—and win. The Canal of Xerxes reveals the power of their adversaries.

The origins of the wars can be found at the dawn of the fifth century B.C., when the Ionian Greeks, who lived along the western coast of modern-day Turkey, revolted against their Persian overlords. In 494 B.C., Persian ruler Darius the Great crushed the Ionian-Greek rebels at the Battle of Lade and then destroyed the Ionian city of Miletus. Having brought the Ionians to heel, Darius sought revenge against their allies—the Athenians.

From this point on, Darius’ fortunes changed abruptly: In 492 B.C., as a large part of the Persian fleet rounded the peninsula of Mount Athos, a fierce storm blasted in from the north. The light and fast Persian warships were vulnerable in adverse conditions. Sitting high in the water, they quickly became unstable in strong winds. The tempest dashed some 300 Persian ships against the cliffs of the peninsula and killed as many as 20,000 sailors.

Two years later, in 490 B.C., Darius was humiliated by Athens on the shore at Marathon and retreated with his forces back to Asia. Distracted by a revolt in Egypt during his last years, Darius died without fulfilling his dream of ruling the Greek world. His son and successor, Xerxes, began meticulous preparations to subdue Greece once and for all.

In spring 480 B.C., Xerxes launched a massive amphibious attack on Greece, a campaign that opened with spectacular displays of military engineering. Xerxes’ first major logistical task in the new invasion was to ferry his vast army across the Dardanelles Strait (also known as the Hellespont) that separates Asia from Europe. A pontoon bridge, constructed of boats tied together, was strung out across the turbulent stretch of water, nearly a mile wide.

Having reached the European side, Xerxes’ armies marched overland along the northern Aegean coast, through the region known historically as Thrace. The Persian navy, meanwhile, followed the coast until meeting the barrier of the Mount Athos Peninsula, just south of the modern-day Greek city of Thessaloniki.

(Betrayal, and Xerxes' fury, crushed Sparta's last stand at the Battle of Thermopylae.)

A man, a plan, a canal

The Mount Athos Peninsula is the eastern-most of three fingerlike promontories that stretch out from the Chalkidiki Peninsula in what is now mainland Greece. At its tip rises the 6,670-foot Mount Athos, regarded as a holy mountain in Orthodox Christianity and today home to a monastic community.

As in the time of Darius and Xerxes, the seas around the mountainous headland of the peninsula can often be hazardous. Motivated by the catastrophic storm that devastated his father’s navy more than a decade before, Xerxes planned a way to avoid the treacherous waters. On arrival, the Persian navy found an even greater engineering project than the pontoon bridge that had enabled them to cross the Dardanelles: As part of his long preparations for the renewed invasion of Greece, gangs of laborers had hacked out a canal, over one mile long, from one side of the peninsula to the other. Through this channel, Persia’s navy would eventually pass in its relentless advance westward.

(A reborn Persian Empire captured Rome's lands—and its emperor.)

Under the lash

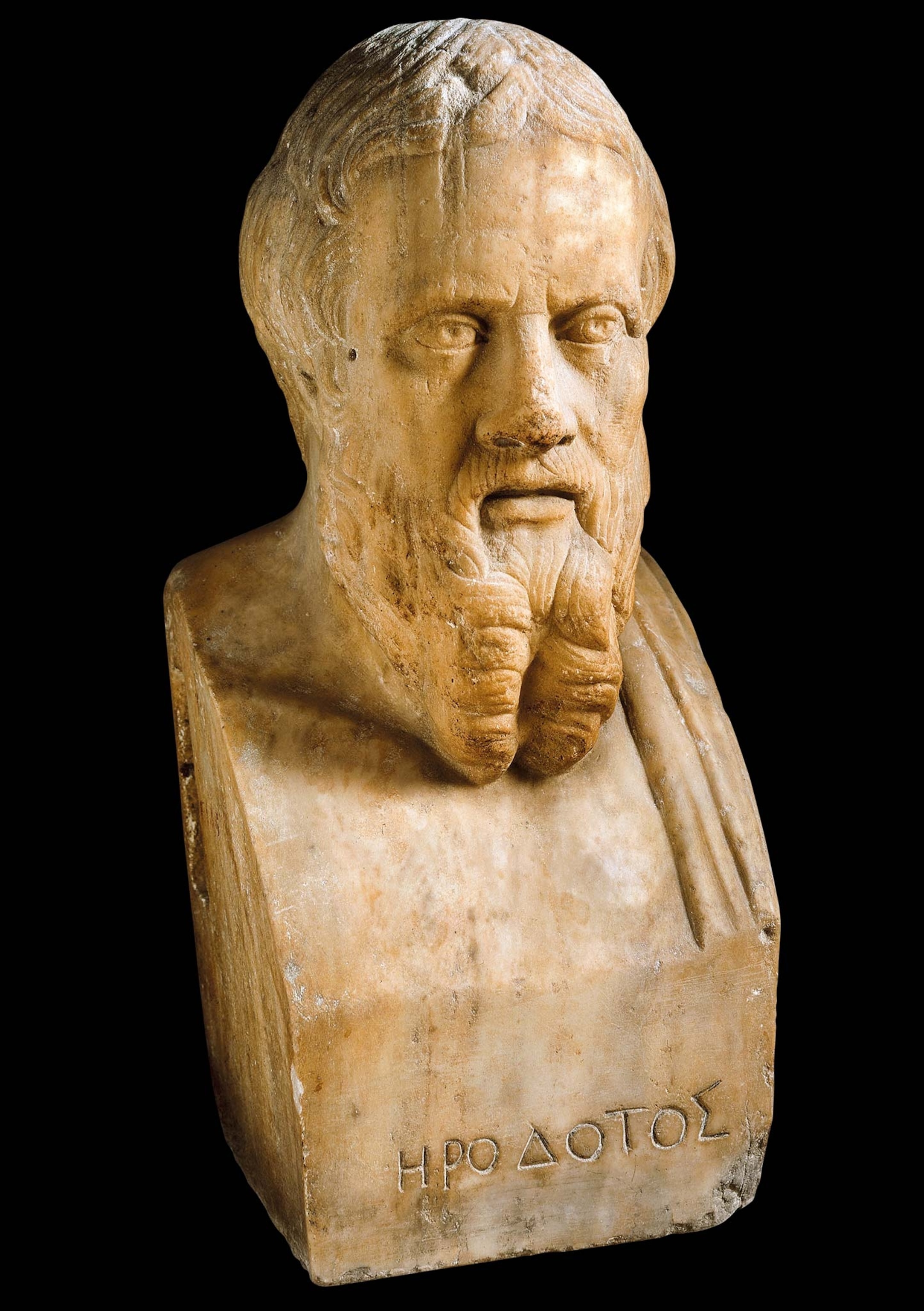

Virtually all the documentary evidence for the canal of Xerxes is found in book seven of Herodotus’ Histories. Writing approximately 50 years after the canal was built, the Greek historian records that “all sorts of men in the army were compelled by whippings to dig a canal” in operations that lasted three years. The canal was sited at “Athos, a great and famous mountain, running out into the sea and inhabited by men. At the mountain’s landward end, it is in the form of a peninsula, and there is an isthmus about twelve stadia wide; here is a place of level ground or little hills, from the sea by Acanthus to the sea opposite Torone.”

The length of a stadium by Herodotus’ calculations has long been debated, but many historians concur that 12 stadia is consistent with the 1.25 miles that make up the width of the peninsula at the site where the canal was believed to have been dug.

Such a project required massive labor, and Persia had access to it. According to Herodotus, it wasn’t just their own men, “compelled by whipping,” who took part in the excavation but people across the locality. As this part of Thrace was under Persian control, every man of military age was obliged to join the expedition against Greece, and some were pressed into digging the canal. Herodotus noted that in order to provide food for the workers, a market was set up nearby (close to the modern town of Néa Roda) and “much ground grain frequently came to them from Asia.” When Xerxes’ army arrived, the regular contingents set up camps, while the monarch and his escort, including his elite corps, known as the Ten Thousand Immortals, stayed in more comfortable accommodations.

After Xerxes arrived in Acanthus, the Persian nobleman Artachaies, who had codirected the canal excavation, died. Artachaies was related to the king and belonged to the Achaemenid clan. Clearly an imposing figure, he was described by Herodotus as “the tallest man in Persia ... and his voice was the loudest on earth.”

(The Suez Canal blockage detoured ships through an area notorious for shipwrecks.)

Xerxes ordered a magnificent funeral in his honor, and the army erected his burial mound right next to the canal he had built. Herodotus described how the army poured out libations for Artachaies while the Acanthians “sacrifice to him, calling upon his name.” If this burial mound exists, it has not yet been discovered, but its presence would be key evidence in confirming the canal’s site.

Phoenician flair

The canal’s southern end is thought to have opened onto a small pebble beach overlooking the inner bay, near a village called Trypiti. Here the terrain is uneven, which would have complicated the excavation work. While the workers dug through layers of relatively soft sediment in other sections of the canal, at this southern end the ground is harder to penetrate. It is difficult to imagine how the workers managed to dig down as much as 80 feet to reach sea level at this point of the channel where it lies between two hills. When Demetrius of Scepsis, a Greek scholar writing in the second century B.C., examined this section, he judged it impossible for the Persians to channel through the rocky terrain.

Herodotus recounts how the digging work was assigned to different working groups who worked solidly for three years. As the Persians were able to count on almost unlimited labor from across the region and beyond, the project could go ahead with only rudimentary techniques. Herodotus wrote: “When the channel had been dug to some depth, some men stood at the bottom of it and dug, others took the dirt as it was dug out and delivered it to yet others that stood higher on stages, and they again to others as they received it, until they came to those that were highest; these carried it out and threw it away.”Some of the excavated rock was used to build breakwaters at either end of the channel, to prevent waves from eroding it and to stop the channel from silting up.

Some time later, Xerxes departed and led his ground troops west toward the city of Terme (present-day Thessaloniki). He ordered his admirals to advance Persia’s ships through the canal and then direct them to Terme, to re-join Xerxes and the ground forces there, which means it is unlikely Xerxes witnessed the fleet sailing through the engineering marvel that bears his name.

Legend or landmark

Since few detailed descriptions of Xerxes Canal (except those from Herodotus) have survived to the modern age, the idea prevailed that his claim was an exaggeration or an out-right invention. The mystery of the canal’s existence lingered for millennia. In the 19th century, interest blossomed in ascertaining whether traces of Xerxes’ canal could be found. Marie-Gabriel-Florent-Auguste de Choiseul-Gouffier (1752-1817) was a French count who served as ambassador to the Ottoman Empire. Passionate about ancient Greek history, he traveled the Aegean Sea aboard a frigate and in 1809 published the second volume of his chronicle Picturesque Journey through Greece, in which he argues that a canal had once existed, cutting straight through the Mount Athos Peninsula. He even drew up a plan showing the measurements and sections in accordance with Herodotus’ account. The romantic tone of his. travelogue, however, and the absence of any rigorous scientific method led to his claims being dismissed.

In 1847, the Royal Geographical Society of London published topographical studies carried out by the sailor and geologist Thomas Spratt. These scientific findings did seem to corroborate the existence of the canal as described by Herodotus. What had seemed a typically tall tale was now gaining plausibility, but it would not be until the end of the 20th century that actual proof of the canal would begin to come to light.

From 1991 to 2001, a multidisciplinary team of British and Greek geophysicists, topographers, and archaeologists worked extensively on the site. It was a major collaboration involving the National Observatory of Athens, the British School of Athens, and universities in Leeds and Glasgow in the U.K. and Patras and Thessaloniki in Greece. Benedikt Isserlin, from the University of Leeds, and later Richard Jones, from the University of Glasgow, directed the decade-long project.

(At the Battle of Marathon, Athens' underdog victory stunned Persia.)

On the Isthmus of Corinth, the spit of land that links the Peloponnese Peninsula to the mainland, researchers have uncovered evidence of boats supported on wooden cylinders or wheeled platforms, which would have been dragged by slaves or animals along a stone causeway from one coast to the other. Isserlin wanted to first check whether such a causeway existed on the Mount Athos Peninsula and consider whether it could explain how Xerxes’ fleet had made the crossing. When no evidence of such a causeway came to light, the team went ahead with geophysical tests to see if they could locate a canal.

Exciting initial results showed there had indeed been some kind of ancient excavation in the middle of the peninsula, about 50 feet above sea level and some 65 feet deep. Taking into account that the sea level of the Mediterranean has risen more than three feet in the last 2,500 years, the team calculated that the depth of the seawater in the channel would then have been about 10 feet. They drilled nine boreholes, which allowed them to analyze the layers of the sub-soil. In the upper section (about 30 feet down), they found several ancient layers of silt. Then came a vital clue below that: a dense bed of reddish solidified sand extending for just over a mile. Here were the canal’s foundations—a wide, solid base.

Crossing the Hellespont

For a decade, researchers on the site used methods typical of oil and mining prospecting, including seismic tests and refraction and reflection techniques. With heavy hammers they struck metal pieces embedded in the ground. They then used geo-phones to record the strength and direction of the impulses generated. They calculated the depth of subsoil layers by measuring the time for the volumetric waves to pass through them. They then linked subterranean points that showed similar acoustic transmission. They also performed electrical discharge and georadar (GPR) tests to get a clearer picture of how the canal was structured.

Radiocarbon dating of the organic elements and high-resolution satellite images were definitive. Using their findings, the researchers created a three-dimensional digital representation of the canal. The Greek-British joint project proved not only that some kind of channel had existed there but also settled the contentious issue of whether it could have run all the way from one coast to the other.

At first, the team had shared the doubts of generations of skeptics who believed a channel could not have been cut across the rocky southern part of the peninsula. But the discovery of the channel bed, the measurements made through seismic waves, and the stratigraphic analysis of the subsoil told a different story. The team also confirmed the channel had been constructed with sloping sides and measurements aligned with those of Herodotus’s description: “from sea to sea, wide enough to float two triremes rowed abreast.” Since the bottom of the channel turned out to be as wide as 50 feet, with the outward sloping walls the navigable space at the surface indeed would have reached the width necessary for two triremes to row abreast.

Having proved the canal’s existence, researchers still ponder the question of why the Xerxes Canal disappeared, both in its physical from and—apart from Herodotus’s account—from Greek memory. No marine remains, such as shells, have shown up in the sediments on the canal bed, suggesting that the channel was filled with seawater for only a short period of time.

The size of the canal was not amendable to larger trading vessels, so it appears it was used only for smaller military ships. There is, however, a plausible theory as to why this infrastructure disappeared relatively quickly: In 479 B.C., the Persian forces were defeated at the Battle of Plataea, and the inhabitants of the Mount Athos Peninsula were freed from the Persian yoke. It follows that they might allow an enemy-built canal to silt up naturally, or even fill it in themselves, thereby obliterating the landmark that symbolized their oppression.