The Christmas Truce of 1914: What historians say really happened

All went quiet on the western front in December 1914, when spontaneous truces broke out between enemy soldiers spending the holidays at war. They decorated, exchanged gifts, and even playing a little soccer.

When World War I broke out in July 1914, many Europeans thought the fighting would be over by Christmas. It wasn’t, and nearly six months after the war began, hundreds of thousands of soldiers celebrated the holiday as best they could in the freezing trenches of western Europe.

Yuletide cheer

Across Europe, holiday campaigns collected and distributed Christmas gifts to soldiers at the front. British soldiers were sent a brass tin embossed with the profile of Princess Mary containing chocolate, tobacco, and a note from the King and Queen reading: “May God protect you and bring you safely home.” German forces received gifts from Kaiser Wilhelm II: Soldiers got pipes, and officers, packs of cigarettes.

A few days before Christmas, French president Raymond Poincaré visited the Paris warehouse where gifts for French soldiers were being amassed. “A large number of packages are ready to be transported to the front; wine producers have provided 1,200 bottles,” the Paris daily Le Temps reported on December 22, 1914.

(What caused World War I and what were its effects?)

Merry little Christmas

Hospital staff made sure that the holiday didn’t pass without a little celebration for the wounded. An American volunteer with the British Red Cross, Mary Dexter wrote letters that detailed holiday preparations: “[T]he day after tomorrow is Christmas ... We are busy, in odd minutes, making gauze stockings for our 200 men—each one will contain fruit, jam, tobacco.” In a Berlin hospital, nurses handed out treats and decorated small Christmas trees.

Louie Johnson, an English nurse, remembered how people gave her simple gifts, such as a pack of cigarettes or a scarf, to pass on to soldiers. German nurse Anna von Mildenburg said this of Christmas 1914: “The image will remain with us forever, how we all stood among the soldiers, hands folded fervently. And by the flickering of the Christmas tree candles, in the fir tree scent of the glittering tree, we sang softly the beloved old song, sending it up as an ardent prayer, a heartfelt plea: Peace to men on Earth.”

Peace of Christmas Day

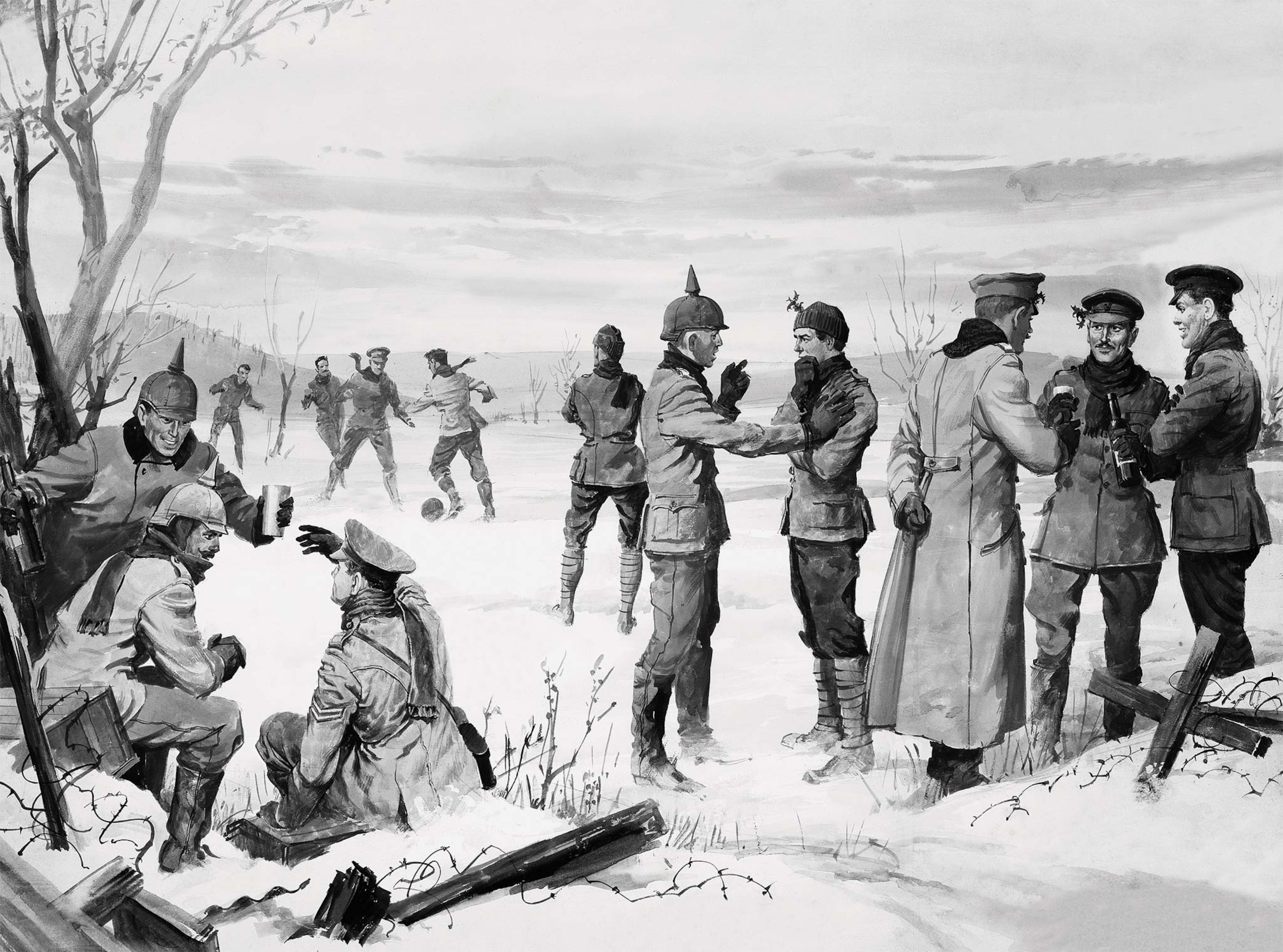

The spontaneous truces that arose along the western front, especially those between British and German forces, are among the most famous events of December 1914. On Christmas Eve, German soldiers in some locations decorated the trenches with Tannenbäume, or fir trees, and sang carols. Wafting across no-man’s-land came a British serenade of Christmas music back to them. The next morning the men spent time together outside the trenches, exchanging greetings and gifts of rum and cigars.

(Why do we have Christmas trees? The surprising history behind this holiday tradition.)

Making merry

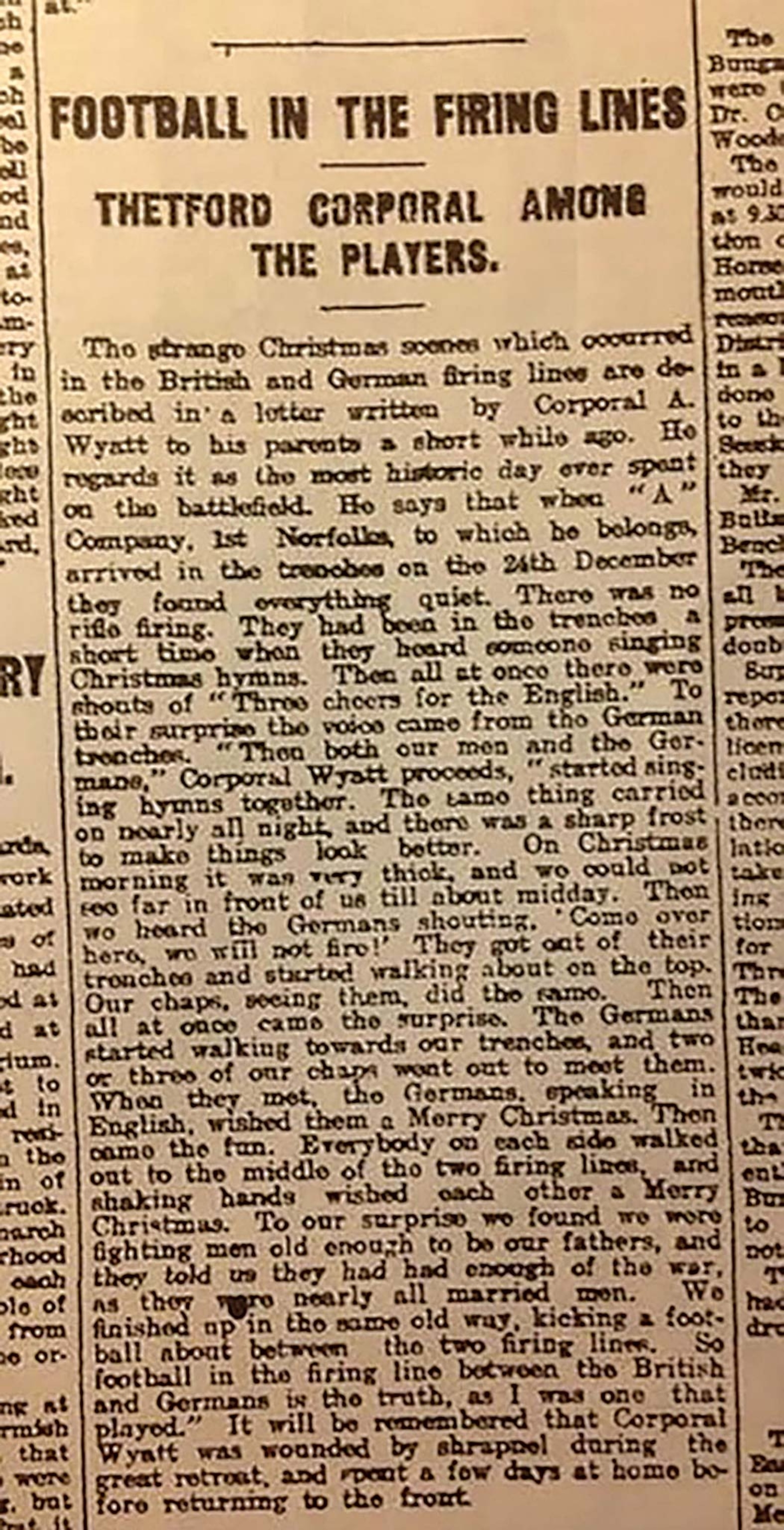

Perhaps the truce’s most uplifting story has been the hardest to document: soccer games played on Christmas Day. Second- and thirdhand accounts appeared in newspapers and letters, but firsthand testimonies, either of witnessing a soccer (football) game or playing in one, were rare.

One “kickabout” was verified by two letters written by British soldiers Corporal Albert Wyatt and Sergeant Frank Naden describing play in Wulvergem, Belgium. Wyatt’s account was published in Thetford Times' article describing “kicking a ball between the two firing lines.”

Using similar methods, historians confirmed another match occurred in Frélinghien, France. Even though the games were smaller and fewer than originally believed, it did not stop commemorations on the truce’s hundredth anniversary in 2014, including a sculpture unveiled in Liverpool, England, and a steel soccer ball atop an exploded shell was presented in Saint-Yvon, Belgium, to honor the games.

(Soccer is the world's most popular sport. But who invented it?)

Christmases yet to come

The truce of 1914 did not last, and fighting soon picked up along the western front. While newspaper accounts of the holiday observance might have charmed people at home, military commanders were horrified. In the three Christmases that followed, they handed down orders that would prevent any further fraternization between the fighting forces. World War I’s unyielding savagery might have made them unnecessary. In December 1914, the war was still young, but as hostilities dragged on, battle-scarred soldiers were hardened after years of horror in the trenches, leading to a different attitude toward “gift exchanges.”

(In 1647, Christmas was canceled—by Christians.)