Frozen shoulder is a real condition—and it mostly affects women

The painful affliction known as adhesive capsulitis can last for years—but has long been ignored by medical researchers who doubted its existence. New treatments may finally promise a cure.

Stirrups, Pap smears, prenatal checks: At her busy office at Duke Women’s Health in Durham, NC, OB-GYN Anne Ford’s work with female patients of all ages usually takes place from the waist down.

But Ford has noticed that a subset of her patients—all women entering or past menopause—come to their appointments with a seemingly non-gynecological issue: adhesive capsulitis or “frozen shoulder,” a poorly understood, often agonizing, uncurable condition that can inflame and immobilize the shoulder joint for months or even years.

In fact, the condition strikes peri- or post-menopausal women more commonly than anyone else: Three-quarters of frozen shoulder patients are female.

“Just being a woman is a risk factor for frozen shoulder,” says orthopedic surgeon Jocelyn Wittstein, whose practice as a shoulder specialist also includes large numbers of patients with the condition.

Surprisingly (or unsurprisingly) little study has been done on the causes of frozen shoulder, until now. Ford and Wittstein, who both teach at Duke University School of Medicine, recently presented research suggesting menopausal hormone therapy—once known as hormone replacement therapy, or HRT—may protect women against adhesive capsulitis.

It’s a first foray into a place where few researchers have gone before. And for those hurtling toward (or experiencing) menopause, it can’t come a moment too soon.

‘Fifty-year shoulder’

Frozen shoulder is thought to affect between 2 and 5 percent of the global population—the vast majority of whom are women between 40 and 60, a life phase that happens to coincide with the transition toward menopause.

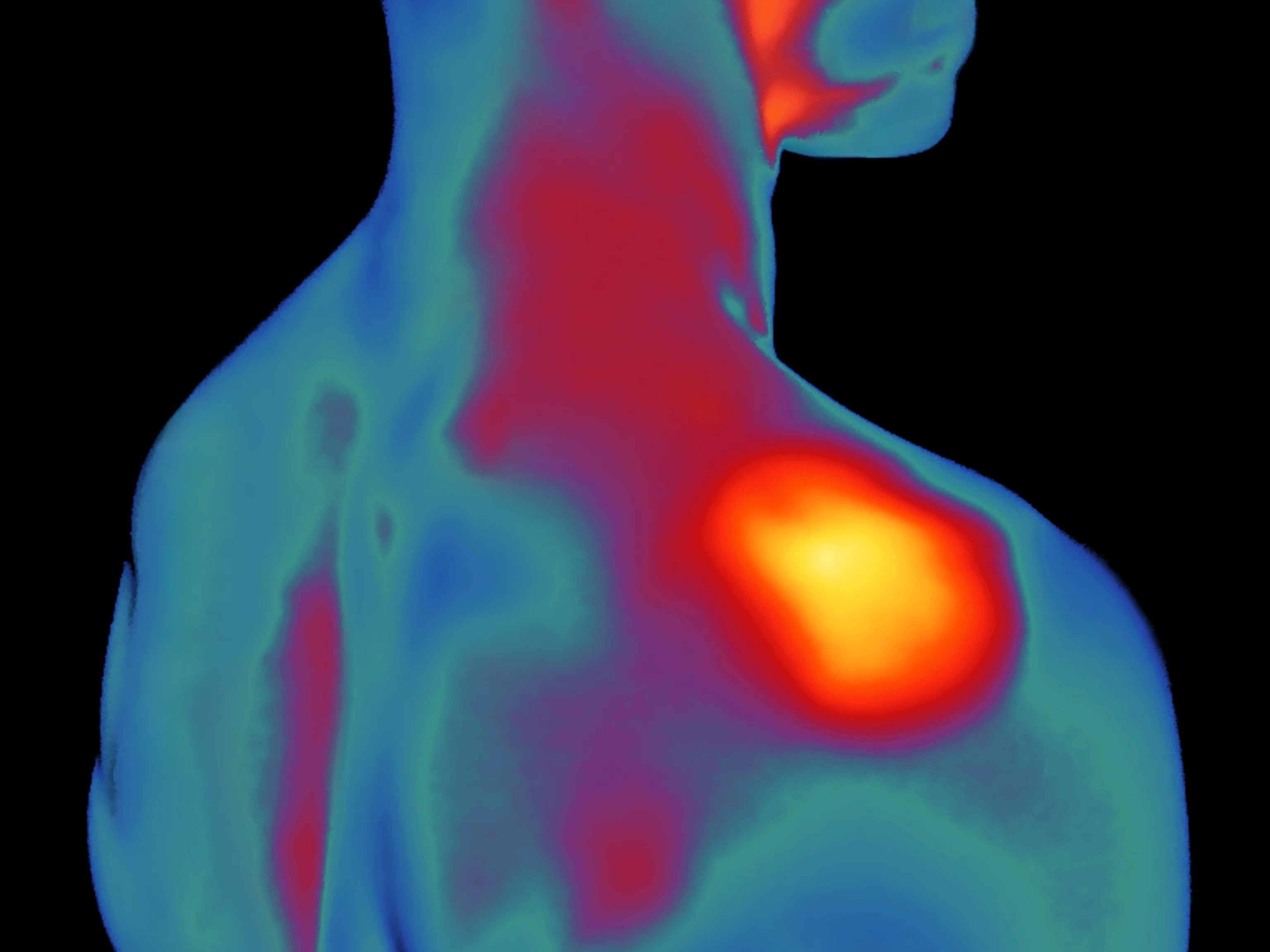

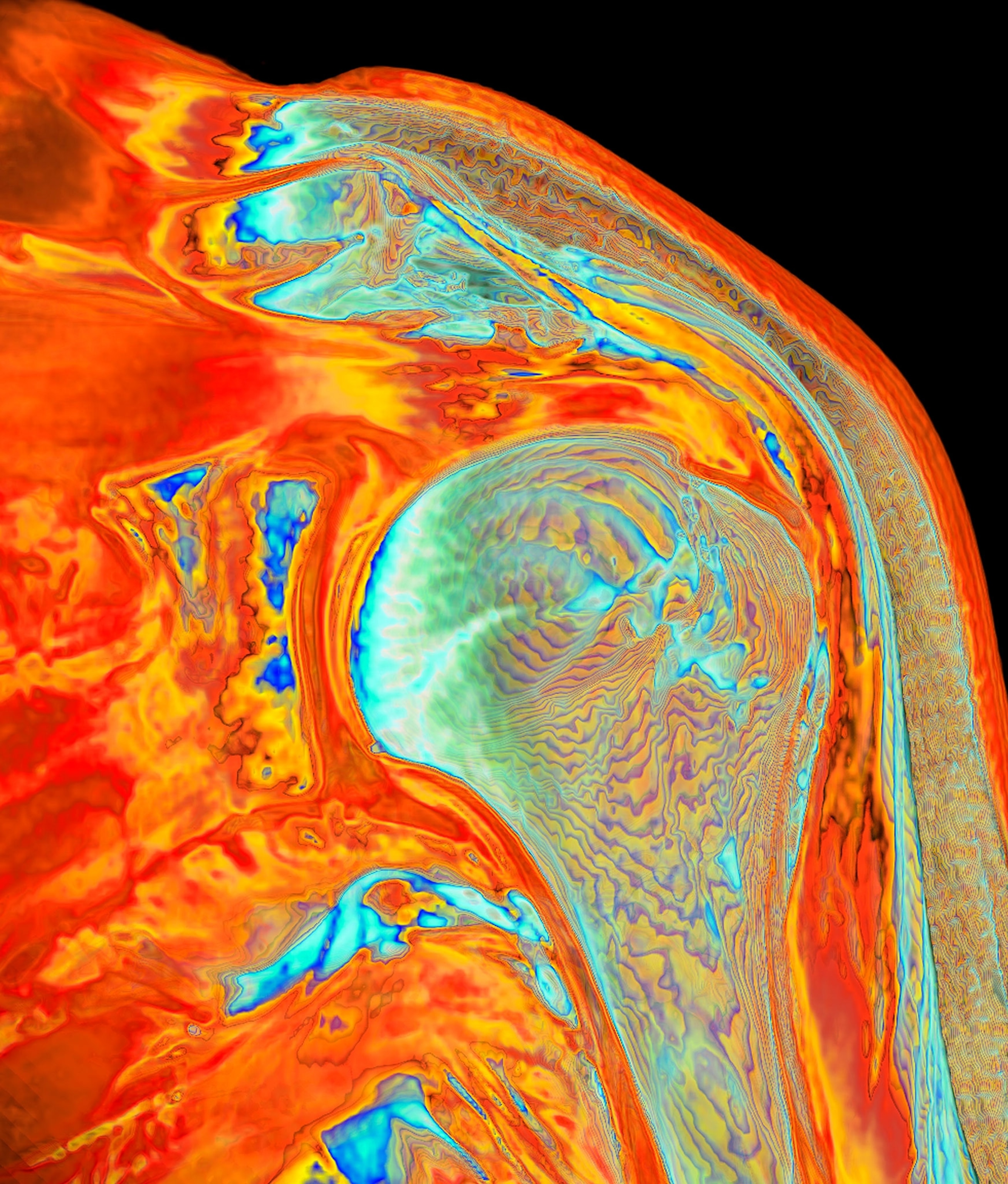

Unlike injuries that develop due to overuse or trauma, frozen shoulder occurs with age, inflaming the connective tissue, or capsule, that surrounds the shoulder joint. During the “frozen” stage of the condition, patients can get trapped in a vicious cycle.

“People push through it, and it gets more inflamed,” explains Wittstein. “Pushing the range of motion is like putting oil on a fire, and it just gets worse.” Though there are treatments—usually oral or injected steroids along with physical therapy and home exercise—there’s no cure for the condition, which can last for months or years. Eventually, the shoulder will “thaw.” But in the meantime, the condition can range from inconvenient to agonizing.

Some people are more prone to the malady than others: those with diabetes, for example, and people of Asian descent, in whom frozen shoulder or shoulder pain and inflammation is the most prominent symptom of menopause, says Wittstein. In fact, in some Asian countries, it’s so common it’s known as “fifties shoulder” or “fifty-year shoulder.”

Estrogen loss and joint pain

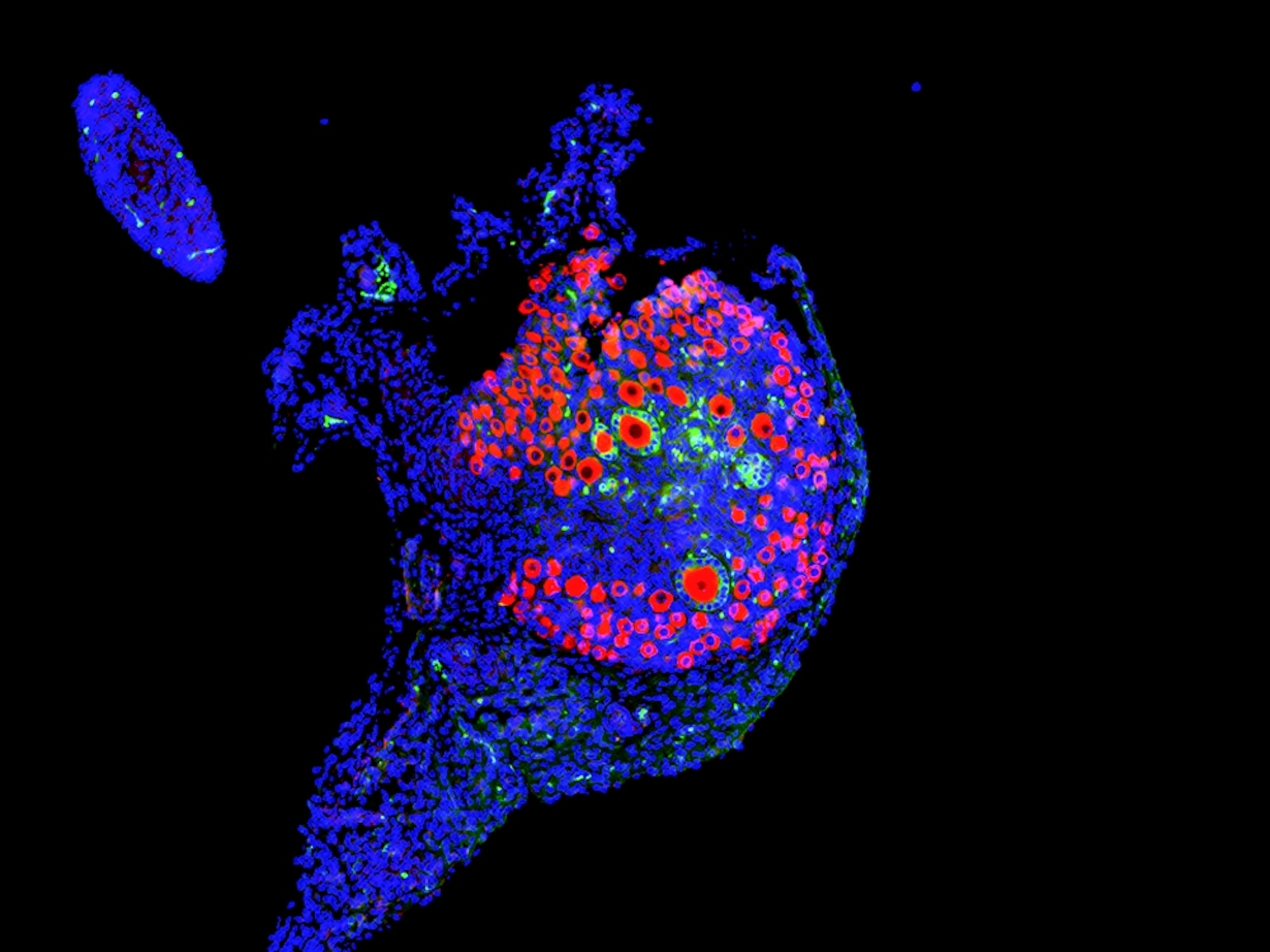

As a woman ages, her ovaries make less estrogen—one of the most prominent hormones in women’s health—and with menopause, they cease estrogen and progesterone production altogether. That shift in sex hormones can affect everything from bone density to the heart and joints.

An estimated 50 percent or more of women experience arthralgia, or joint pain, during menopause. But estrogen’s effects on the musculoskeletal system are understudied and poorly understood—and there’s no comprehensive cure for menopause-related joint pain.

In a bid to understand more, Ford and Wittstein compared shoulder symptoms in people undergoing menopausal hormone therapy and their counterparts who don’t boost their estrogen levels with medication. They conducted a retrospective study of 1,952 female patients between 45 and 60 years of age, analyzing their medical records for signs of menopause, use of hormone therapy, and frozen shoulder symptoms or diagnoses.

About 8 percent of the patients—152 of them—used hormone therapy. And those who didn’t hormone therapy had 99 percent greater odds of receiving a frozen shoulder diagnosis than their counterparts who did.

The sample size was small, and the odds, though high, don’t reach statistical significance due to the study size, the physicians note. But after presenting their research to supportive colleagues at both the North American Menopause Society and the American Orthopedic Society for Sports Medicine, they now plan to expand their research to a wider population.

“The basic science makes sense,” says Wittstein, noting recent research that reveals estrogen activity in skeletal muscle. But the doctors say that a better understanding of estrogen and joint health has thus far proved elusive. Bias, a lack of research, a health care system that privileges symptoms over whole-patient care, and public mistrust of menopausal therapy have hindered progress for years, they say—and in the meantime, menopausal women’s shoulders keep on freezing.

‘Frozen personality’ and ‘hysterical traits’

“Ninety-four percent of orthopedic surgeons do not experience menopause,” notes Wittstein, citing statistics that show women constitute just 6 percent of practicing orthopedic surgeons.

Another barrier is a public fear of hormone treatment, says Ford. Despite evidence that estrogen supplementation can alleviate menopausal symptoms and lower the risk of bone fractures, stroke and other conditions, the public remains wary of hormone treatment due to misinformation spread in the wake of a landmark 2002 study that showed some adverse outcomes from early forms of the treatment. Though hormone replacement has become safer, Ford says, the public’s attitudes haven’t caught up with current medical practice. As a result, noted one research team in a 2022 literature review, “Despite readily safe hormonal and non-hormonal interventions, most women with bothersome menopausal symptoms do not receive effective, approved evidence-based therapy.”

It could also prove hard to get to a scientific consensus on how estrogen affects menopausal joints for a more insidious reason: a lack of urgency driven by menopause stigma and the medical profession’s ongoing failure to acknowledge and investigate women’s pain. Women with pain wait longer for treatment than their male counterparts and can be diagnosed with psychiatric problems instead of being given treatment. One 2022 study showed that when middle-aged women presented for coronary heart disease, they were 31.3 percent more likely than their male counterparts to be diagnosed with a mental health condition rather than their underlying illness.

That issue exists in orthopedics, too, and has a surprisingly long history in the realm of frozen shoulder. Though the term “frozen shoulder” was first coined in 1934, the definition of the condition is still debated, as is the existence of menopausal arthralgia altogether.

In the 1970s, provider bias and ongoing confusion about the condition collided when British researchers released a study on the personalities of 40 women with the condition.

“There remains an anecdotal impression shared by many clinicians that the condition occurs often in a typical personality type—‘frozen’ shoulder in a ‘frozen’ personality,” the researchers wrote. They concluded that women with the condition showed “premorbid” anxiety, insecurity, and increased “hysterical traits” compared to 14 men studied.

There’s more to learn about how estrogen impacts muscles and bones—tantalizing evidence from other researchers links a pregnancy hormone called relaxin to frozen shoulder symptom relief in pregnant people. But Ford and Wittstein say that since such research is in its infancy, people’s best bet to fend off issues like frozen shoulder is to engage in regular weight-bearing exercise, eat a healthy diet, and realize that their increasing aches and pains might be a sign of menopause.

Eventually, hormone therapy may be used to stave off painful ailments like frozen shoulder. In the meantime, those suffering from the condition continue to wait for answers as tenacious researchers chip away at the cold shoulder many scientists have historically given women’s health.