Does this ‘secret room’ contain Michelangelo’s lost artwork? See for yourself.

Sketches on the walls of a hidden room in a Florentine chapel may have been the work of Michelangelo, who sought refuge from the Medici family in 1530.

Florence, Italy — In 1975, Paolo Dal Poggetto, then director of the Medici Chapels museum in Florence, stumbled upon a Renaissance treasure.

While searching for a new way for tourists to exit, Dal Poggetto and his colleagues discovered a trapdoor hidden beneath a wardrobe near the New Sacristy, a chamber housing the ornate tombs of Medici rulers. Below the trapdoor, stone steps led to an oblong room that at first appeared to be little more than a storage space used for coal.

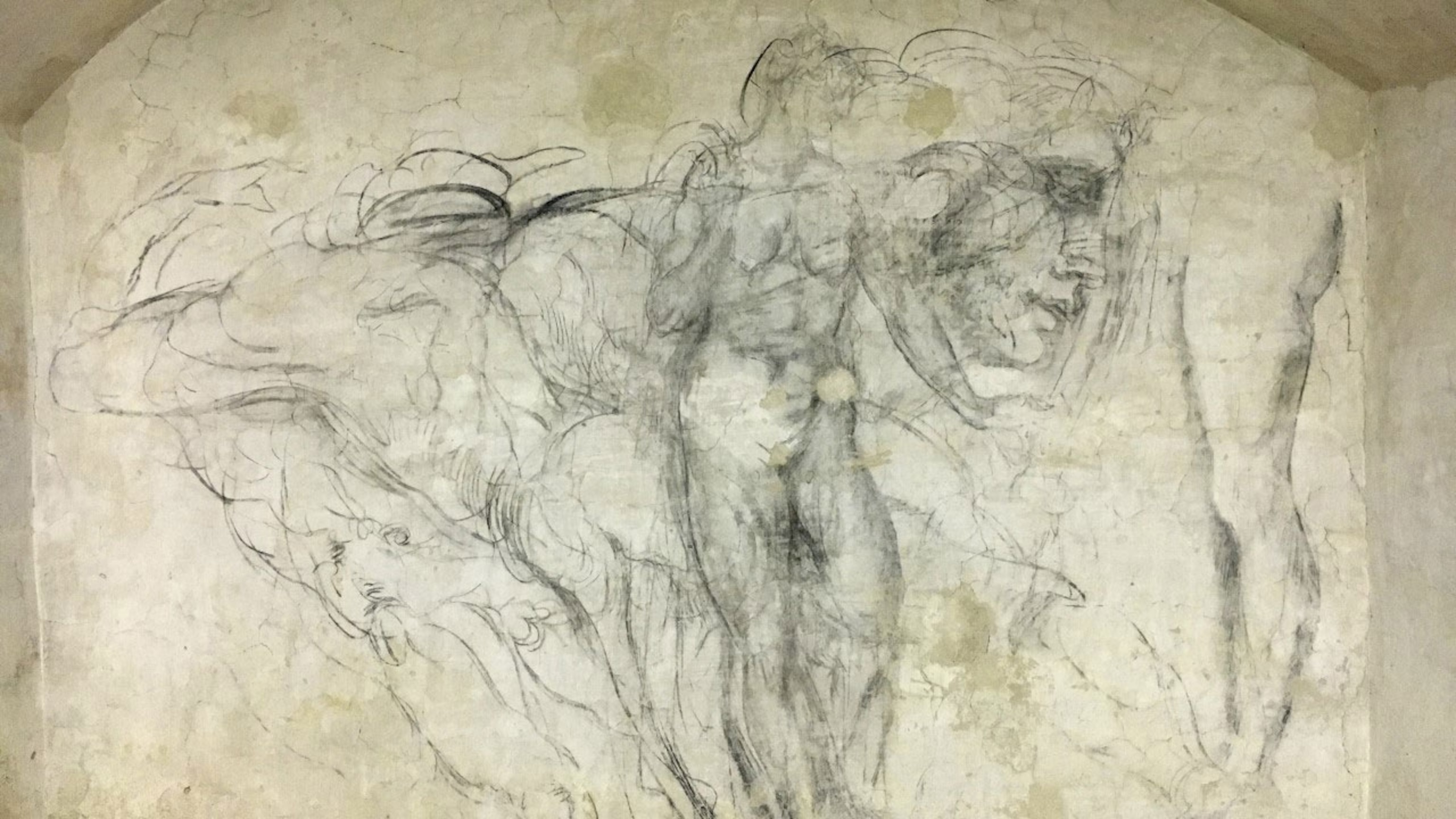

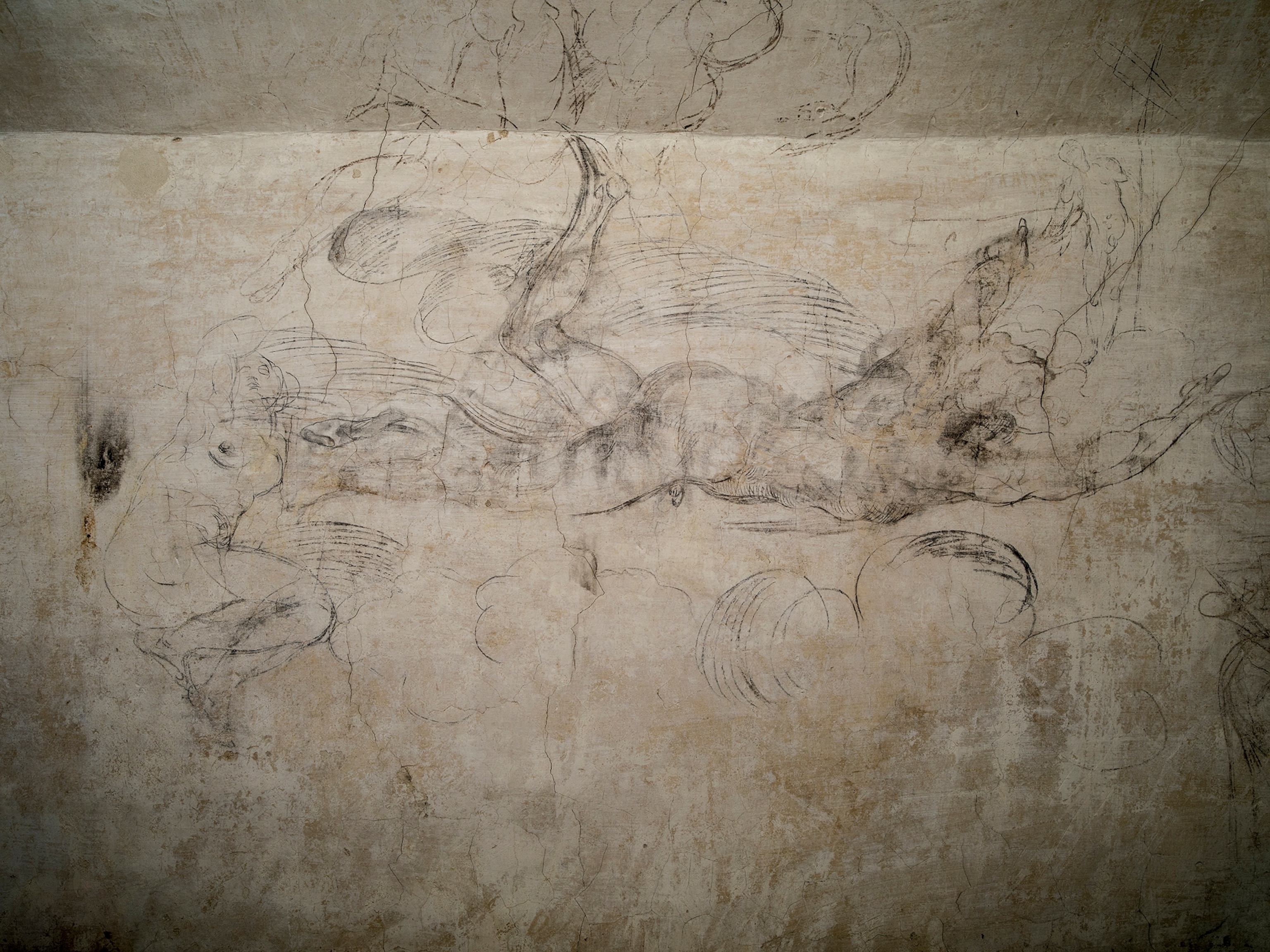

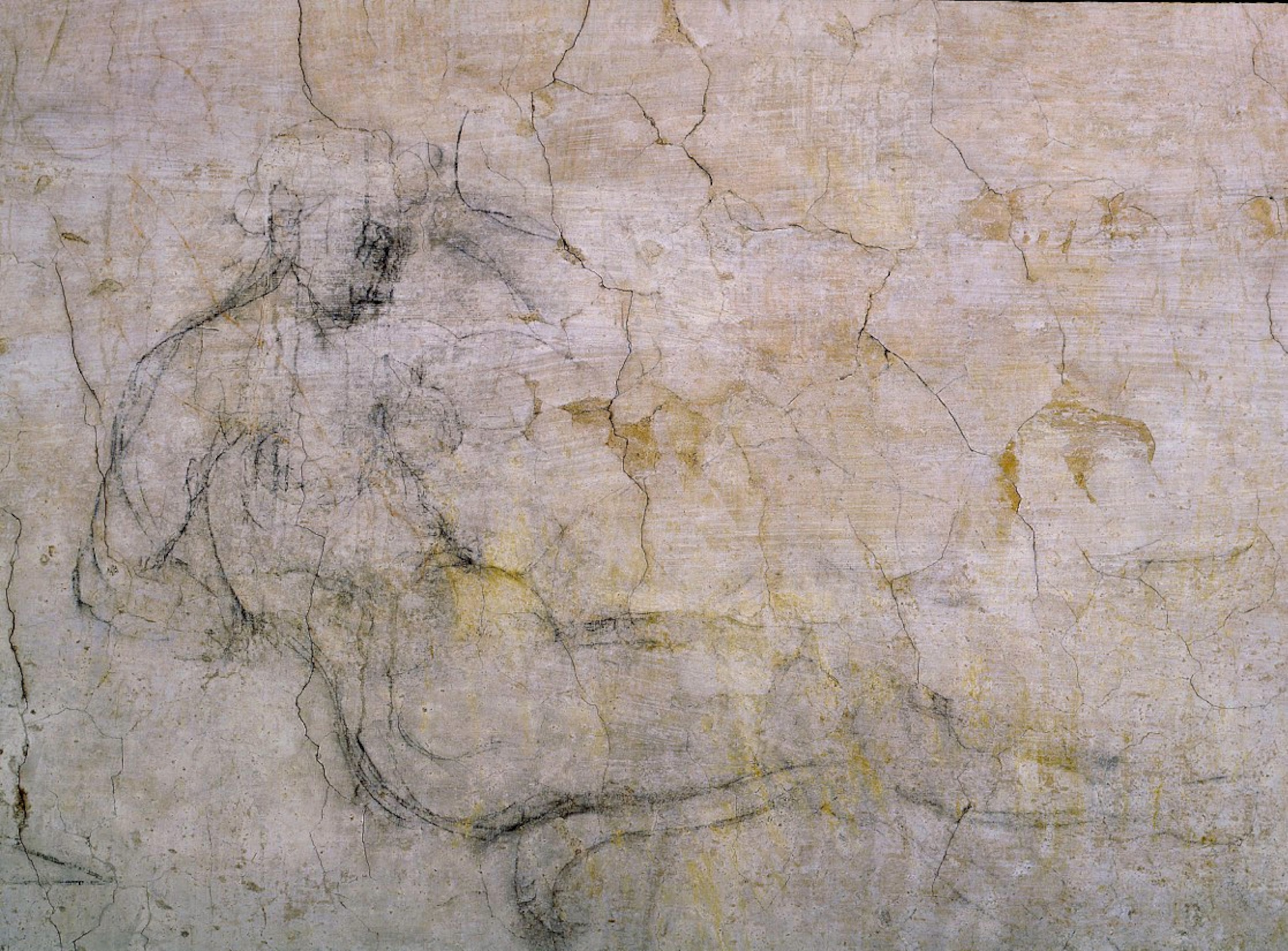

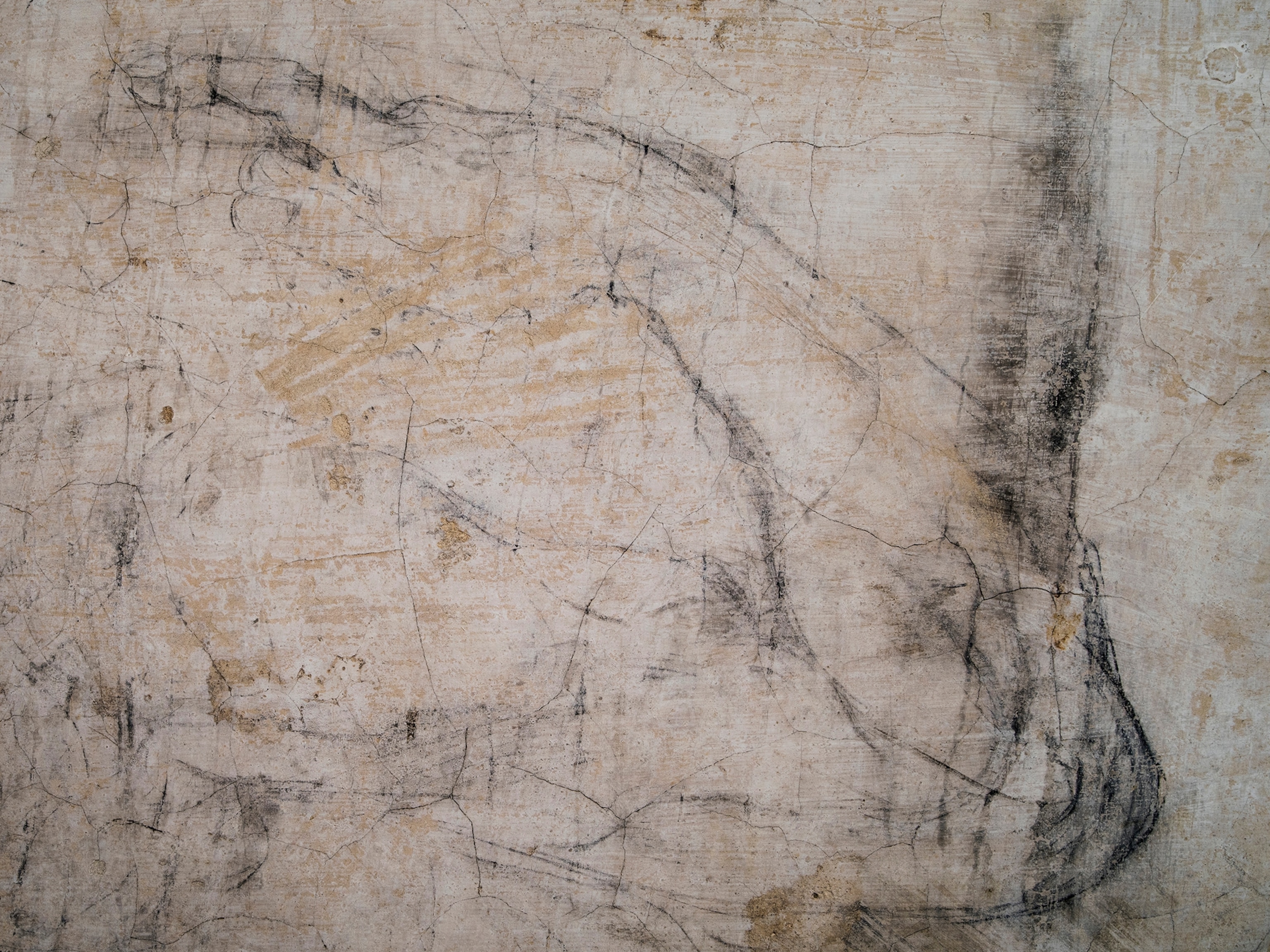

But on the walls, Dal Poggetto and his colleagues found what they believe are charcoal and chalk drawings from the hand of famed artist Michelangelo. Until now, the room has been largely off-limits, but on November 15 it will open to the public on a trial basis for a ticket price of 20 euros. Four visitors, accompanied by museum security, will be allowed to visit for up to 15 minutes at a time.

Accessible by a narrow staircase, the room is just 33 feet long, 10 feet wide, and eight feet high. In 2017, Monica Bietti, who was director of the Medici Chapels at the time, granted National Geographic photographer Paolo Woods rare access to capture its remarkable contents.

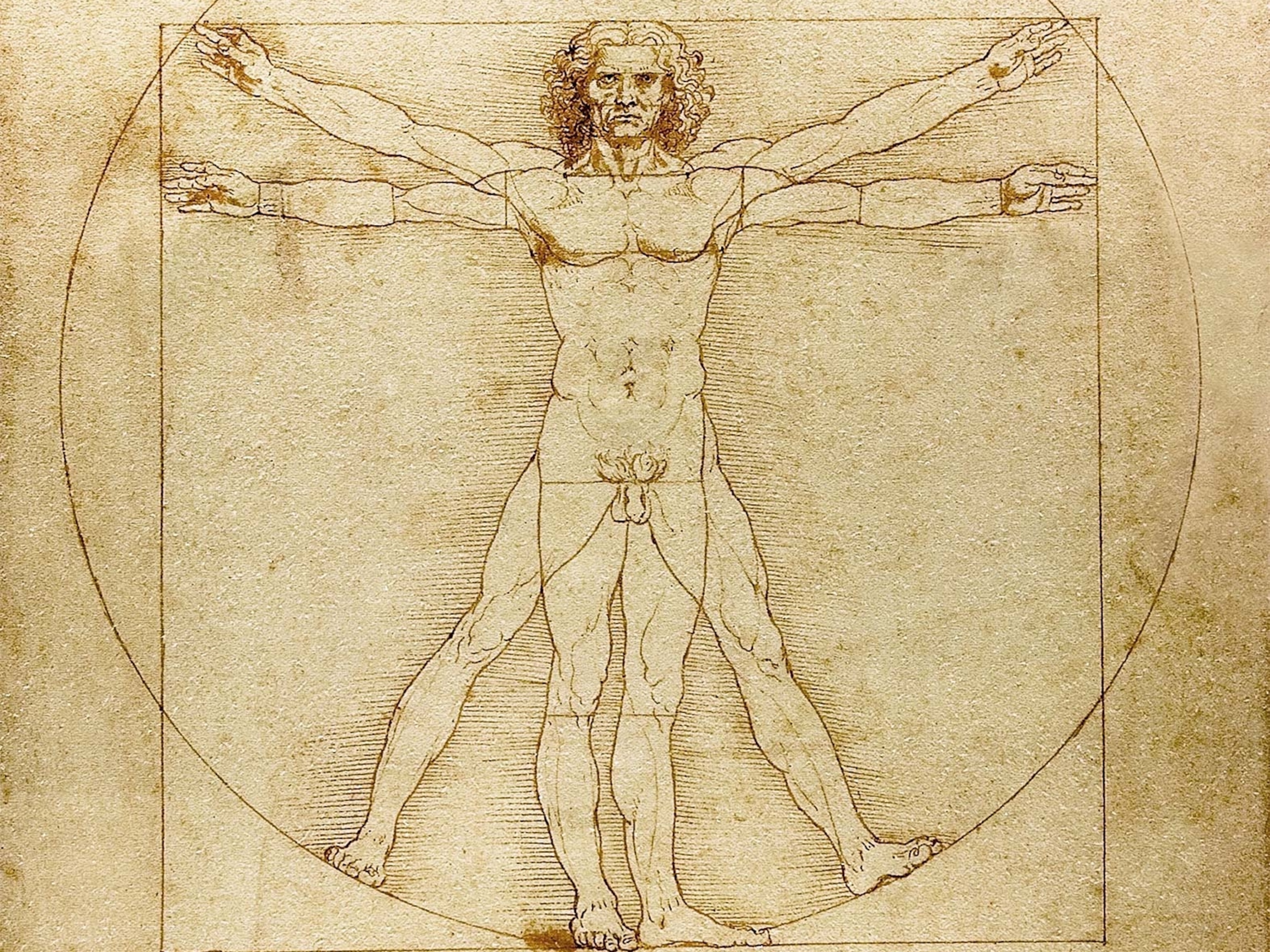

(What makes a genius? Inside some of history's most exceptional minds—including Picasso and Leonardo.)

The artwork is visible today because Dal Poggetto took no chances when he first entered the space. This being Florence, home to many of history’s towering Renaissance artists, he suspected something valuable might be lurking underneath the layers of plaster.

“When we have very old buildings, we must pay attention,” Bietti told National Geographic in 2017. Because the drawings are unsigned and undated, two questions remain up for debate: Who drew them? And precisely when?

An artist in hiding?

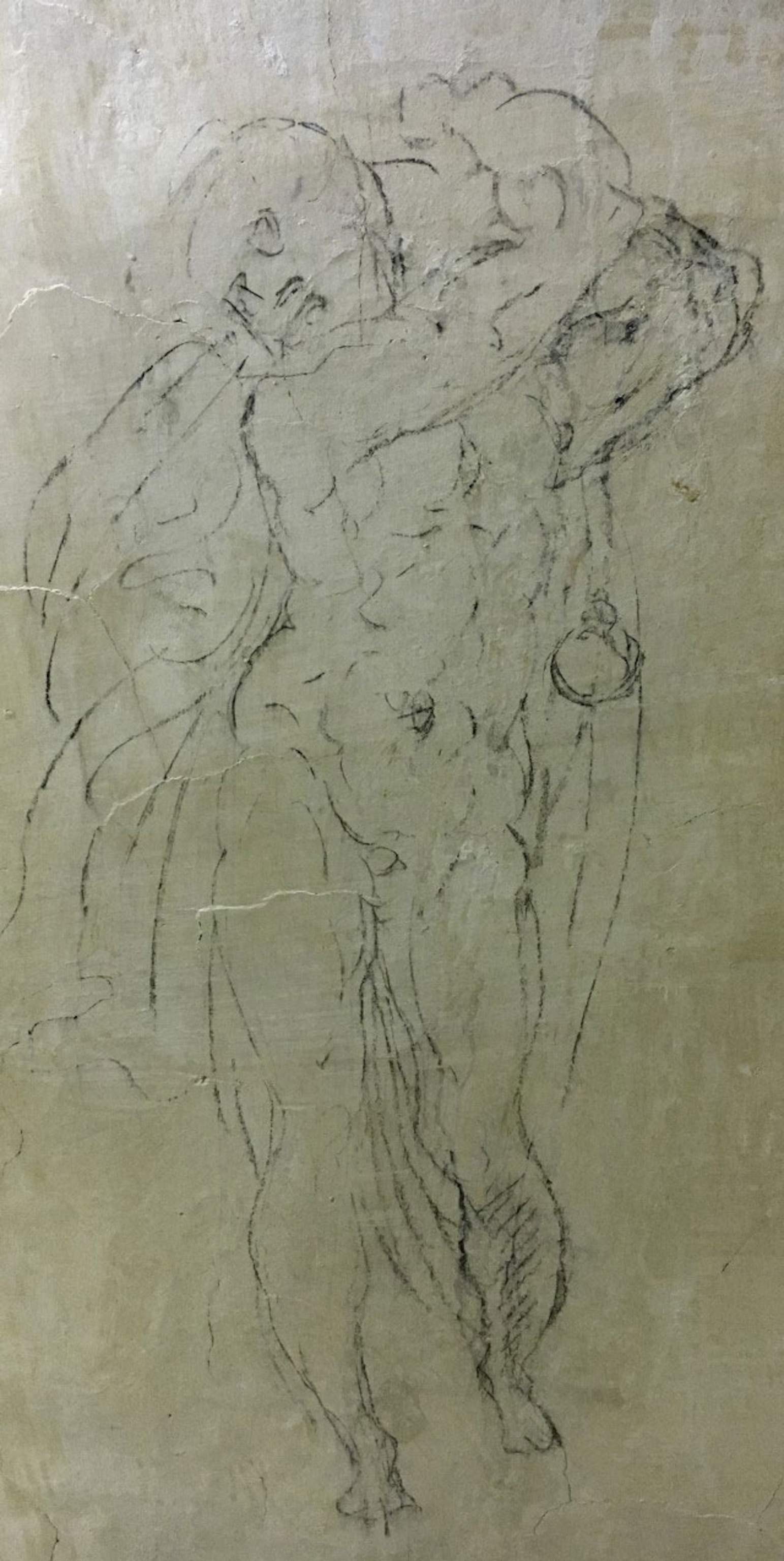

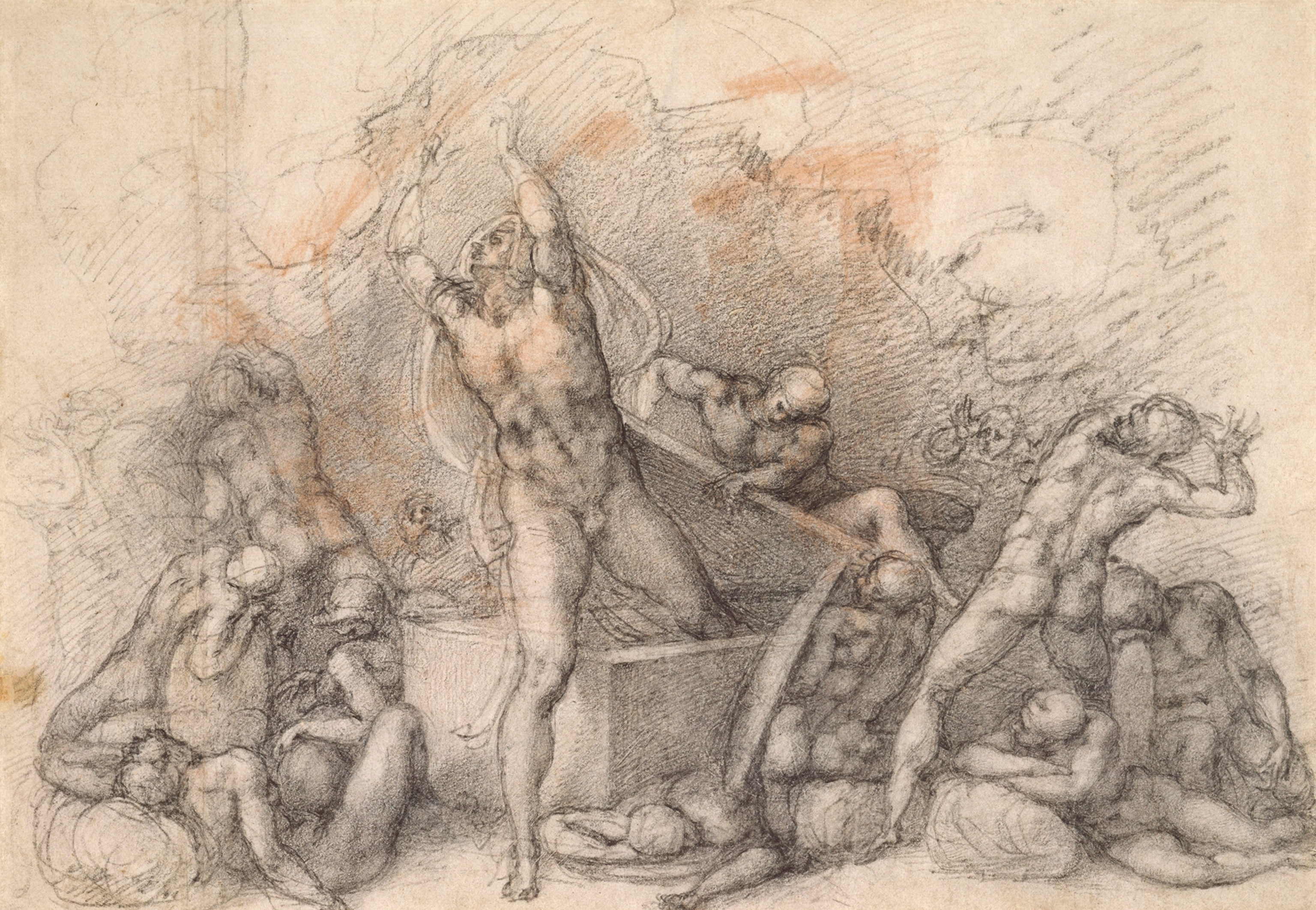

Under Dal Poggetto’s direction, experts spent weeks meticulously removing the plaster with scalpels. As the coating disappeared, dozens of drawings emerged, many of them reminiscent of Michelangelo’s great works—including a marble sculpture of a human figure adorning the tomb of Giuliano de’ Medici in the New Sacristy above, which Michelangelo himself designed.

Dal Poggetto concluded that the artist took cover inside the room for about two months in 1530 to hide from the Medici family. A popular revolt had sent the city’s Medici rulers into exile in 1527, and despite their previous patronage of his work, Michelangelo had betrayed the family, aligning himself with fellow Florentines against their rule.

(How Machiavelli exposed the truth about Renaissance politics.)

With their return to power a few years later, the 55-year-old artist’s life was in danger. “Naturally, Michelangelo was afraid,” said Bietti, “and he decided to stay in the room.”

Bietti said she suspected that Michelangelo spent his sequestered weeks taking stock of his life and his art. The drawings on the walls represent works he intended to finish as well as masterpieces he completed years earlier, she said, including a detail from the statue of David (finished in 1504) and figures from the Sistine Chapel (unveiled in 1512).

“He was a genius,” she said, spurred by his boundless creativity. “What can he do there? Just draw.”

Lingering doubts

As with any centuries-old artwork, it is impossible to confirm the origins of the drawings with absolute certainty. The consensus seems to be that some of the doodles on the wall are far too amateurish to be Michelangelo’s. But the provenance of the rest of them remains a matter of opinion.

(Inside the Sistine Chapel, Michelangelo's masterpiece.)

After the 1975 discovery, a prominent Renaissance art authority hailed the collection of sketches as one of the major artistic finds of the 20th century. But William Wallace, a Michelangelo scholar at Washington University in St. Louis, is skeptical.

Wallace believes that Michelangelo was too prominent to have holed up in the lower-level room, and instead he would have been taken in by one of his other patrons. He also suspects that the drawings were completed earlier, sometime in the 1520s, when Michelangelo and his many assistants would have taken respites from laying brick and cutting marble for the New Sacristy they were building above.

Given these uncertainties, Wallace takes issue with the characterization of the space as “secret.” The room contains a well, which he believes Michelangelo and his assistants would have used to mix mortar and plaster, clean off tools, and drink during hot summer months. They’d be going up and down those stairs all day long, Wallace told National Geographic in 2017 and reaffirmed in a recent email. “That was no ‘secret’ room, but an integral part of the building.”

Several of the drawings might be Michelangelo originals, Wallace says, but others were likely depictions by workers sorting out artistic dilemmas or simply amusing themselves during breaks.

“Separating one from the other is almost impossible,” he says. Still, he adds that the mystery of who crafted the drawings does not take away from their value or the importance of the discovery.

“Being in that room is exciting. You feel privileged,” he says. “You feel closer to the working process of a master and his pupils and assistants.”

The room evokes an emotional response among viewers lucky enough to see it. Standing within its four walls, dimly lit by a small corner window, it’s as if one is peering into the mind of Michelangelo, whose breathtaking artistry fills the building.

“This is a person who had infinite capacity,” says Wallace. “He lived to be 89 years old and never stopped getting better and better.”