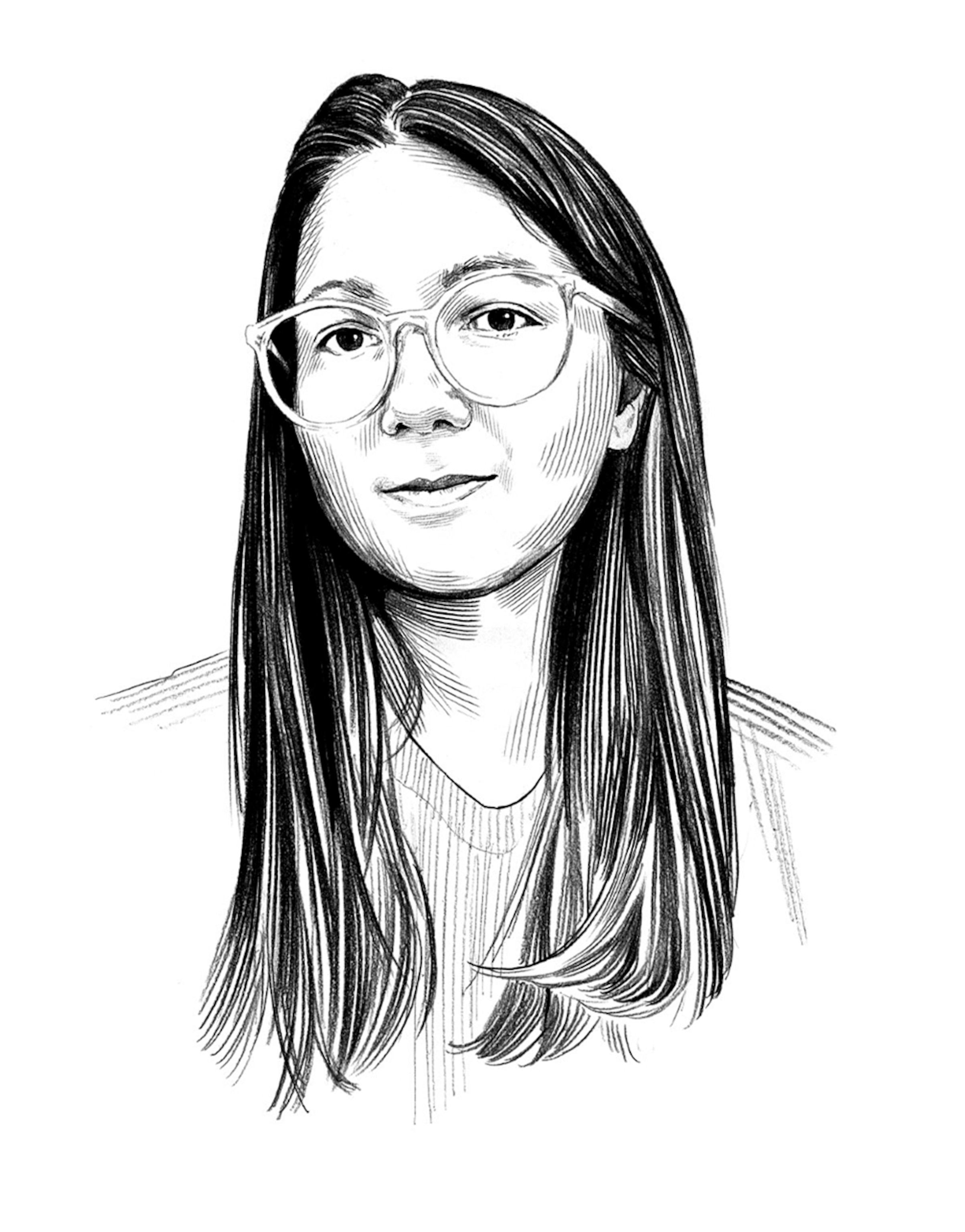

They were taken from their families as children. Can that trauma be healed?

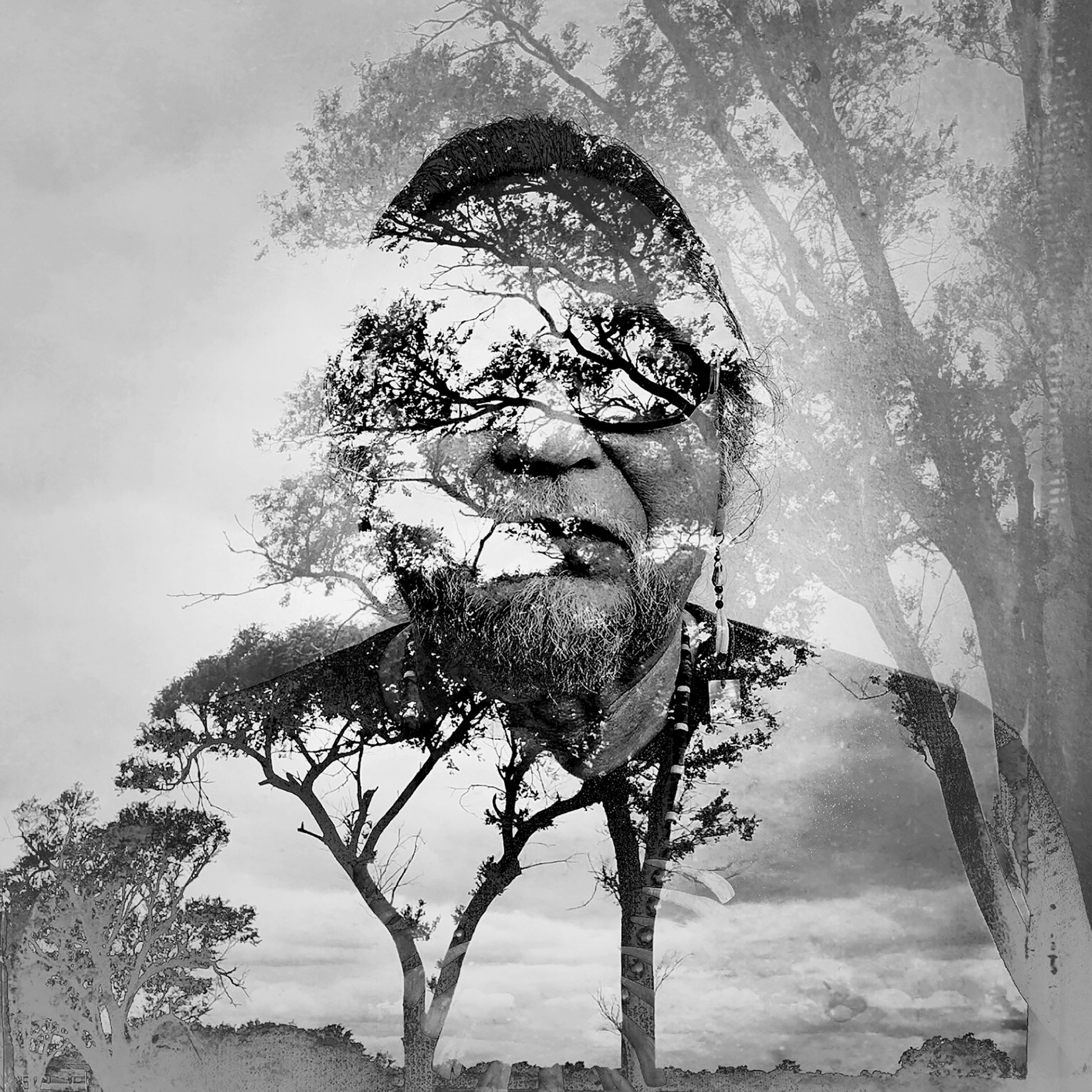

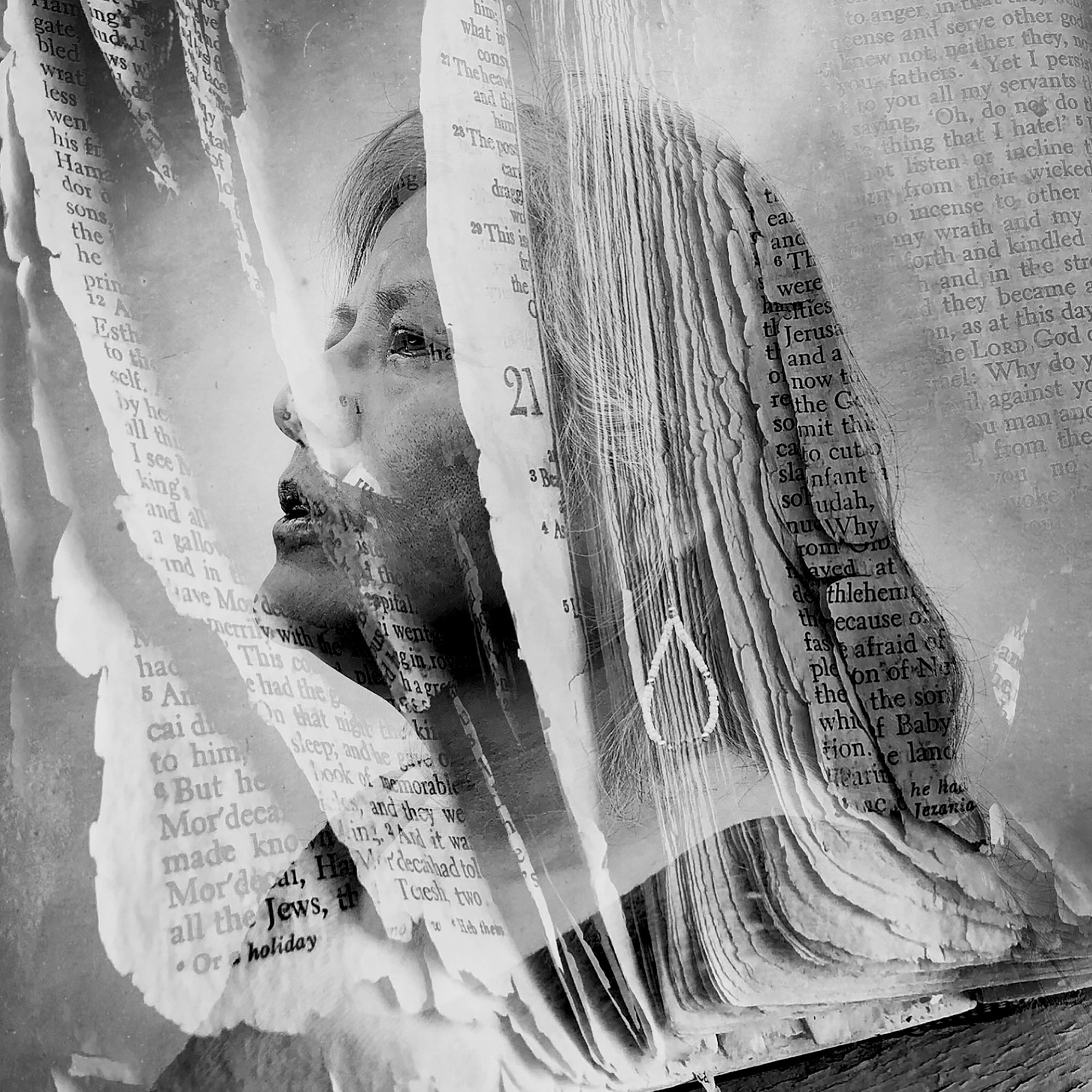

For centuries, Indigenous children were removed from their families and placed in missions and boarding schools. For former students like those in these portraits, the reckoning has just begun.

Patricia Whitefoot doesn’t remember everything from her time at the Yakima Indian Christian Mission, a boarding school on the Yakama Indian Reservation in Washington State.

“I do remember the runaways,” says Whitefoot, who says she was five or six at the time. “I would witness the older girls running away, and we all had to keep a secret as the girls prepared to run away from the mission. And we did.”

Whitefoot, now 73, also remembers missionaries showing up at her grandparents’ house on the reservation. Soon afterward she found herself in a dormitory with other Native girls. For the next few years, her life consisted of rules, farmwork, and little affection from the adults in charge.

What she can’t forget is the cloud of otherness, fear, and control that permeated her childhood.

“I was raised by my maternal grandparents, who were very loving and nurturing and compassionate,” says Whitefoot, a citizen of the Yakama Nation with ancestry from Taidnapam, Klickitat, Skiin, Spokane, and Diné (Navajo). “But I began to realize that there was something amiss.”

Her grandmother had “outbursts,” which jolted Whitefoot and her sisters. They did not understand where her anger was coming from.

“Then my grandmother began to talk to me about it,” says Whitefoot.

She slowly realized that her grandmother was struggling with severe trauma from her time at the Fort Simcoe Indian Boarding School in White Swan, Washington. Like similar schools across the United States and Canada, Fort Simcoe had a mission: Educate and Christianize Native children to assimilate them fully into the dominant culture’s way of life.

But as evidence gathered over the past few decades reveals, hundreds of thousands of American Indian, Alaska Native, Canadian First Nations, and Native Hawaiian children were forced to attend these schools that typically had little to do with education or Christianity. For many Native peoples, the schools were ongoing nightmares of reprogramming, abuse, child labor, and torture that continue to haunt Native families and communities to this day.

From the moment Columbus dropped anchor off the shores of the Bahamas in the late 15th century, Native children became prize pawns in the battle for the subjugation and domination of the Western Hemisphere. European missionaries, operating under papal bulls that outlined the Doctrine of Discovery, began distancing Native children from their parents by establishing mission schools in which the kids were little more than unpaid laborers.

In the mission system, “education” was code for Catholic conversion. Native children were de facto hostages who endured slavery, forced labor, debt peonage, violence, and sexual abuse. “Ecclesiastical slavery” is how a British merchant described it after visiting the California missions. These brutal human rights abuses, perpetrated by the Roman Catholic Church, went on for centuries.

The U.S. government continued the use of education as a tool for subjugating Indigenous peoples. The Indian Civilization Fund Act of 1819 funneled federal money to Protestant and Catholic churches to found boarding schools “for introducing among [the Indian tribes] the habits and arts of civilization.” In practice, that meant cultural eradication and forced religious conversion. This policy led to the eventual creation of government-run boarding schools, beginning in 1879 with the Carlisle Indian Industrial School, founded by Richard Pratt, an Army officer whose experiments in assimilation with Native prisoners became the blueprint for “Indian education.” His stated mission: “Kill the Indian in him, and save the man.”

(A century of trauma at U.S. boarding schools for Native American children.)

Native children as young as four were forcibly rounded up. Parents who resisted were imprisoned and denied food rations on the reservations as punishment. In 1886, Mescalero and Jicarilla Apache refused to hand over their children to U.S. Indian agent Fletcher Cowart. “The Indian police,” he reported, “had to chase and capture them like so many wild rabbits.”

Parents who resisted surrendering their children were imprisoned and denied food rations on the reservations as punishment.

When children arrived at the schools, their long hair and braids were cut and their traditional clothes taken away. Forbidden from speaking their languages or practicing their spiritual beliefs, the children often lived in overcrowded dorms amid unsanitary conditions: Diseases such as tuberculosis and measles were rife, nutrition poor, and medical care inadequate.

They were routinely subjected to physical, psychological, and sexual abuse by the same people who had been charged with protecting them. Runaways from schools were chased down by professional trackers and brought back to face severe punishments, including rape by their bounty hunters, for attempting to escape. In 1930 Congress held hearings about accusations that staff at the Phoenix Indian School in Arizona flogged a student to death and whipped “some 80 little boys who ran out of bounds to see a merry-go-round,” among other brutalities.

“We weren’t human to the missionaries, and you could see it in the way they stared at you,” says Whitefoot. “That’s one of the things I do remember: that stare.”

(These Indigenous children died far away more than a century ago. Here's how they finally got home.)

Some students died from disease or suicide. Others perished under mysterious circumstances—buried without death certificates and interred in unmarked graves, their families given little information about what had happened to their children. In Canada, 4,127 First Nations children are known to have died in residential school custody, though the Canadian government stopped recording deaths in 1920. The top official at the country’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission speculated the true figure “could be in the 15,000 to 25,000 range, and maybe even more.” Since 2021, more than 1,700 potential unmarked graves have been located in Canada.

That same year, Secretary of the Interior Deb Haaland, a member of the Pueblo of Laguna, New Mexico, launched the Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative to “undertake an investigation of the loss of human life and the lasting consequences of the Federal Indian boarding school system.” More than 500 deaths have been identified, though the Department of the Interior has warned that these numbers could grow to tens of thousands as the investigation unfolds.

For all the sorrow and trauma, students often had nothing tangible to show for their so-called education. Many worked long hours as low-paid or even free labor for local families and businesses. Though more than 100,000 Native children are estimated to have attended these schools in the U.S., educational outcomes were abysmal. At Carlisle, for example, only a few hundred students of the many thousands who were enrolled during the school’s 39-year history received high school diplomas.

Meanwhile, Native schoolchildren were cut off from what their cultures could teach them. “We get tagged with the myth of the hunter-gatherer, but that was hardly the case,” says Kevin Gover, the undersecretary for museums and culture at the Smithsonian Institution and a citizen of the Pawnee Nation of Oklahoma. (His father and grandmother attended the Fort Sill Indian School near Lawton, Oklahoma.) “That was the narrative that [policymakers] told themselves to justify their actions—that we were not really human. But there were hundreds of very complex cultures, which had enormous achievements in architecture, mathematics, and science. And so much of that knowledge, of course, was intentionally destroyed or has since become lost.”

When students returned home, they discovered that the indoctrination and abuse they’d experienced made them strangers. Reconnecting with family was hard: Often the children had lost fluency in their tribal tongue, while their parents did not speak English. Sometimes they were shunned by their communities for having forgotten their languages and ceremonies and for wearing Western clothing—for becoming “white.”

Nor were they adequately prepared for skilled jobs, having been mostly used as farmhands, laborers, or servants. When they escaped to the cities as adults, the former students were denied work, housing, and loans because of entrenched racism in a society that had falsely promised that education and assimilation were the ticket to success. Instead, many wound up homeless or in menial jobs, while many more went into the military as the only path to employment, fighting wars for a country that not only had failed in its trust and treaty obligations to tribes but also continued to engage in efforts to eradicate Native peoples, who were not granted American citizenship until 1924.

(North America's Native nations reassert their sovereignty: "We are here.")

For decades, however, the survivors suffered in silence. Few talked about the trauma they experienced at boarding school. They held on to the horror and shame, struggling to survive and often falling into alcoholism, violence, and dysfunction in a generational cycle that continued with every new student.

The boarding school program ended in 1969 as part of the Johnson administration’s push to begin addressing the poverty, destruction, and plight of Native American communities. But other federal policies that arose from the boarding school era perpetuated the cycle of pain for tribal communities, says Deborah Parker, the CEO of the National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition.

“Boarding schools were the first ‘Indian child welfare’ policy established by the federal government, and after they closed, the U.S. sought other ways to pursue and monetize Native children in the adoption and foster care industries,” says Parker, a member of the Tulalip Tribes of Washington State.

The American Indian Adoption Project, for example, was enacted in 1958 specifically to place Indigenous children with non-Native families, based on assumptions of white supremacy and middle-class values. Meanwhile, foster care systems began placing as many as 35 percent of all Indigenous children with almost entirely non-Natives. This practice became so widespread that Congress passed the Indian Child Welfare Act in 1978 to prevent the total destruction of Native communities by the states.

In 2019, Parker began working with then congresswoman Deb Haaland to draft legislation creating a federal commission similar to Canada’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission. But the bill, and a parallel one in the U.S. Senate, has not yet been brought to a vote. Among the stumbling blocks is the issue of how to locate school and student records, many of which are scattered, incomplete, destroyed—or in the hands of religious institutions reluctant to acknowledge this painful past.

Patricia Whitefoot is now retired from a decades-long career in Native education. Her experience at the mission school inadvertently led her to a life in service of finding better, more culturally competent, and appropriate ways to respectfully and humanely meet the educational needs of Indigenous students.

“I feel that we’re at a point of reckoning with not only boarding schools but all of the intersections of our own humanity as Native people,” says Whitefoot, who has three children, 10 grandchildren, and several great-grandchildren. “And this work has to be done in a very compassionate way that is holistic and collective, where we’re all working toward the same goal of truth, justice, and healing of our people.”

The nonprofit National Geographic Society, committed to illuminating and protecting the wonder of our world, funded Explorer Daniella Zalcman's work. Learn more about the Society’s support of Explorers.

This story appears in the May 2023 issue of National Geographic magazine.