The goal of this pediatric palliative program is clear: Put family first.

For children facing life-threatening diagnoses, one Pittsburgh medical team works to provide equal parts care and comfort. Even if that means prioritizing time spent with friends and family over daunting procedures.

On a mild Saturday morning in early June, Jamie Tezbir braced herself for a grievous decision. She was making her second trip to the emergency room in a week. Hospital runs had become routine for Jamie and her husband, Don, for nearly a decade. But this time felt different.

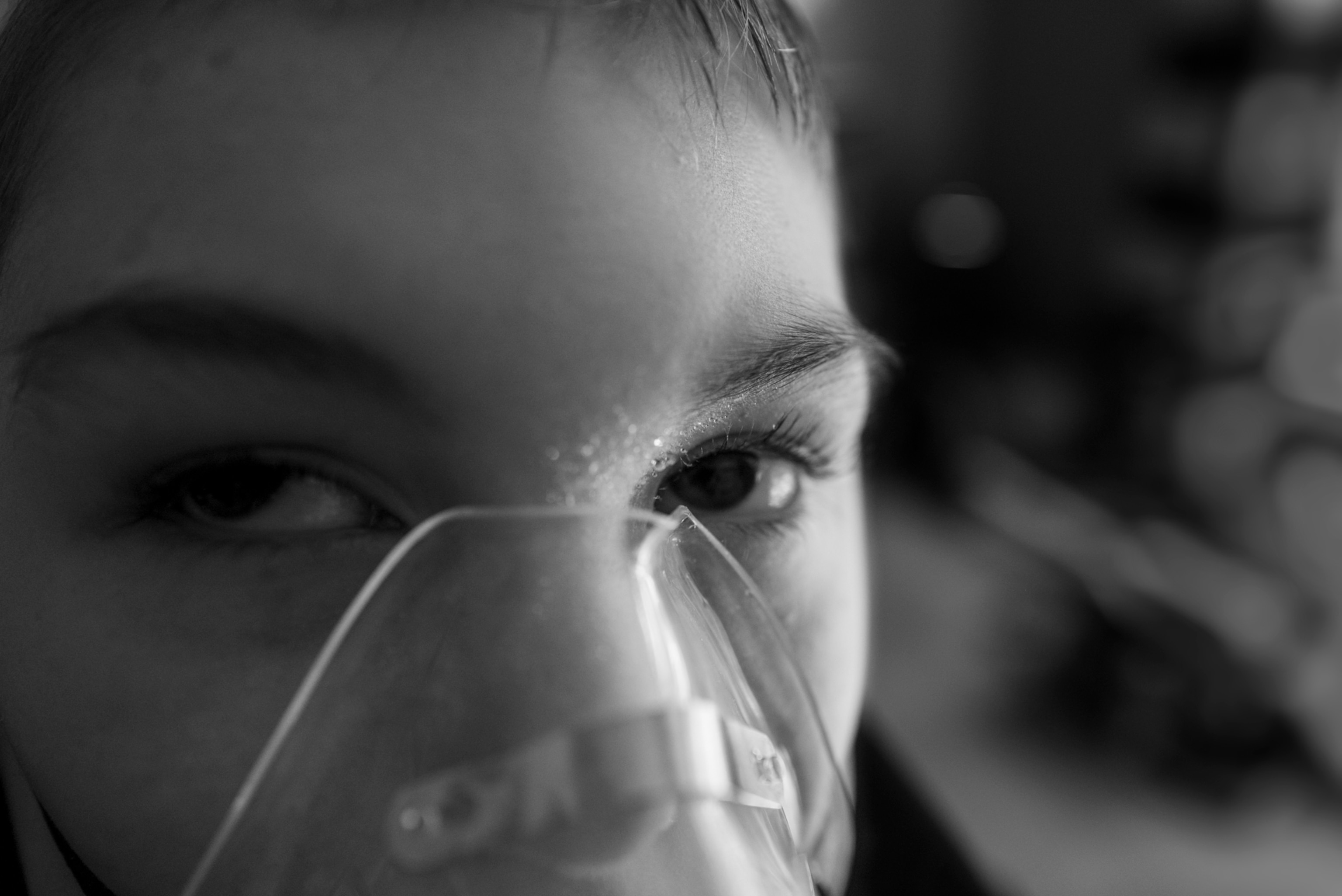

Their son Jackson, then nine years old, had been born with lissencephaly, an incurable brain malformation that triggers frequent seizures. Through the night and into that morning, the attacks had come every 20 minutes. And now his breathing was in severe distress. Jamie and Don had recently signed a do-not-resuscitate order; should Jackson go into cardiac arrest, it would be abided by. But were they receptive to intubation? ICU doctors and anesthesiologists stood ready. “It was one of those scary moments,” Jamie said. This, she feared, “was what the end would look like.”

As has become her practice in fraught moments, Jamie called Carol May, director of the Division of Palliative Medicine and Supportive Care at UPMC Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh. A great many advances have been made in medical care that allow children with complex chronic conditions to live longer. But some families, like the Tezbirs, are choosing to prioritize quality of life. May’s team provides palliative and hospice care, which includes liaising with specialists and coordinating logistics for home-based care. They are there to advise, to advocate, to help realize a family’s wishes for their child.

Palliative care is about keeping kids comfortable while managing their symptoms. Hospice is founded on a philosophy of “neither hastening death nor prolonging life,” said Scott Maurer, the medical director of UPMC Children’s Hospital’s supportive care program. It focuses on the child’s “physical, emotional, social, and spiritual comfort.” May, Maurer, and their colleagues believe that, in most cases, home is where comfort and well-being are best nurtured.

Bedrooms can be outfitted as mini-ICUs. A specialist is a telehealth screen away. A return to routines is encouraged: the family as one.

Emma, Age 3

On a Friday afternoon in August 2022, Maurer was making his hospital rounds. “Oh my gosh,” Maurer said to Kylie McMullen, age six at the time. “We’re twins.” They’d just learned that both are partial to the crust of pizza. Also, both love unicorns. “A match made in heaven.”

Kylie had been diagnosed that February with stage 4 alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma. At the time, Maurer estimated Kylie’s chances of surviving it at little better than 10 percent. She had suffered mightily from secondary issues: a collapsed lung, the trauma of a bone marrow biopsy. In consultation with the doctors, her parents, Sean and Kirsten, had decided to pursue a form of chemotherapy and bring Kylie home, with hospital visits as needed.

By autumn of 2023, Kylie was doing remarkably well and was able to focus on the impor-tant things, like what she was going to be for Halloween. “We’ve been throwing around lots and lots of ideas,” Kirsten said. A witch was one contender, but Mulan won out. Kylie’s final IV chemo treatment was scheduled for November 9, after which she’d move to daily oral doses. If her scans continued to look good, she’d be treatment free.

Kylie, Age 6

For Kylie’s younger sister, Quinn, this experience has been disorienting. You can see Quinn’s trying to process what her family is going through, Sean said. Back in the worst of it, she would say Kylie was “big sick.”

“Honestly,” Sean said, “I haven’t heard Quinn use ‘big sick’ since probably last spring [in 2022].”

Like many palliative care programs, UPMC’s traces its history to the heart and mind of a nurse. When May was 17, her grandfather, who had been diagnosed with lung cancer, was at home for his final days. She knew then she’d found her calling. This, she told herself, is how a loved one should pass: embraced in the familiar, surrounded by family.

Pediatric palliative care is a balancing act. “It’s OK to hope for a miracle,” Maurer said, but “if I stop asking after they tell me their first hope—which is always the miracle—then I’m not going to understand the values that are driving them.” All decisions must be filtered through those values. And it’s a partnership.

Jessica Mitchell’s daughter, Genivive, now eight, was exposed to E. coli in the womb, which led to the development of cortical dysplasia and epilepsy. Unable to speak, she communicates through subtle means. Is she sensitive to her mom’s disquietudes? “Oh God, yes,” May acknowledged during a Saturday visit to check in on the well-being of mother and child. “When Jessica wants to openly express herself—in many different manners—she does so.” Jessica smiled. She’s a fierce advocate for her daughter.

Jessica said she is always alerted to May’s arrival by the authoritative click of heels, a detonation of laughter. Though the sounds are ever welcomed, she much prefers to hear them emanating from the sidewalk outside her Scottdale, Pennsylvania, apartment than from a UPMC corridor. Being in the hospital aggravates Genivive. For Jessica, it’s unsettling. “I know she’s going to die there eventually,” Jessica said. “You’re not in a peaceful place [mentally].”

Genivive recently went more than 16 months without a hospital visit, which Jessica called “a world’s record” for her daughter. “I’ll put it this way: I take care of Genivive, but Carol keeps her alive,” said Jessica. “What can I do for you today?” May is likely to say upon greeting them. And in parting, “What more can I do?” Though there may be no immediate needs, May is on 24/7.

The Tezbirs can testify to May’s gift. Intubating Jackson after his scare in June ultimately proved unnecessary; his condition was deemed recoverable. May was there on the phone, consulting and calming Jamie while coordinating with one of the doctors in the room. “She talked me out of my panic,” Jamie said.

Jackson returned home three days later. But as his need for medications to control his seizures increases, Jamie said, those “glimpses of enjoyment, of happiness,” are vanishingly rare. His mom and dad are exhausted, in every conceivable sense. “I want this to be over,” Jamie said, “but I don’t want to lose him … I don’t know what it will be like to not wake up to him, or hold his hand, or smell his hair.”

Jamie and Don know the next critical moment is likely near. They take solace that the UPMC team sees Jackson not as a neurology or pulmonology patient but as Jackson, their child. The team has offered the “grace,” Jamie said, to accept what she and Don ultimately decide is best for Jackson.

“It’s a privilege to tell someone’s story,” Lynn Johnson says. With her camera and her compassion, she tackles challenging subjects that often reveal “the heroic nature of humanity.” She was a Pulitzer Prize finalist for her work on National Geographic’s Gender Issue and received the National Geographic Society’s 2019 Eliza Scidmore Award for Outstanding Science Media, in part for her cover story on a groundbreaking face transplant. An Explorer since 2017, Johnson is based in Pittsburgh but spends most of her time on the road.