Sugar doesn’t actually make kids hyper—here’s why so many believe it does

The idea of kids getting a “sugar rush” emerged in the 1970s, and the myth continues despite evidence to the contrary.

Sno-cones, soda, ice cream, popsicles—summer is upon us, and that means your kids have likely been eating more sweets than usual.

But does an influx of sugar actually cause hyperactivity in children, as many parents believe?

The idea of a “sugar rush” started gaining traction back in the 1970s, in large part thanks to a best-selling book by pediatric allergist Ben Feingold, Why Your Child Is Hyperactive. In the book, Feingold argued—with little evidence—that food additives, including sugar, are linked to excitable behavior in kids.

However, the association between sugar and hyperactivity has since been thoroughly debunked in two thorough and well-regarded reviews of the research, in 1994 and 1995.

The overwhelming consensus from researchers is “there is no association—none,” says Mark Corkins, chair of the American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Nutrition. (Read more about the history of our sugar obsession.)

And yet, the sugar high myth remains—and is stronger than ever. So what’s going on?

Think about what events are associated with high sugar intake, says Corkins, who is also a professor at the University of Tennessee Health Science Center. “Birthday parties, reunions, Christmas time, Thanksgiving.”

Pool time, backyard BBQs, picnics, beach days. Are you starting to see a pattern?

“When we look at the times that kids have high sugar intake, it’s usually associated with when they’re going to be hyper, even if you didn’t give them any sugar,” he says.

In other words, being ensconced in a celebratory environment with relatives and friends who children might not see every day is itself a very strong stimulant.

The science of sugar

Diana Schnee, a registered pediatric dietitian with Cleveland Clinic Children’s in Ohio, says she has seen anecdotal evidence of sugar rushes firsthand.

However, “there are a lot of things that can explain kids’ hyperactivity and change in emotions,” says Schnee. “One of them being that they’re children, and that’s a very typical thing.”

What's more, eating highly refined carbohydrates can cause inflammation, which may affect a child’s behavior, she says. Likewise, not eating enough fruits or vegetables can lead to constipation, which can also cause discomfort and moodiness.

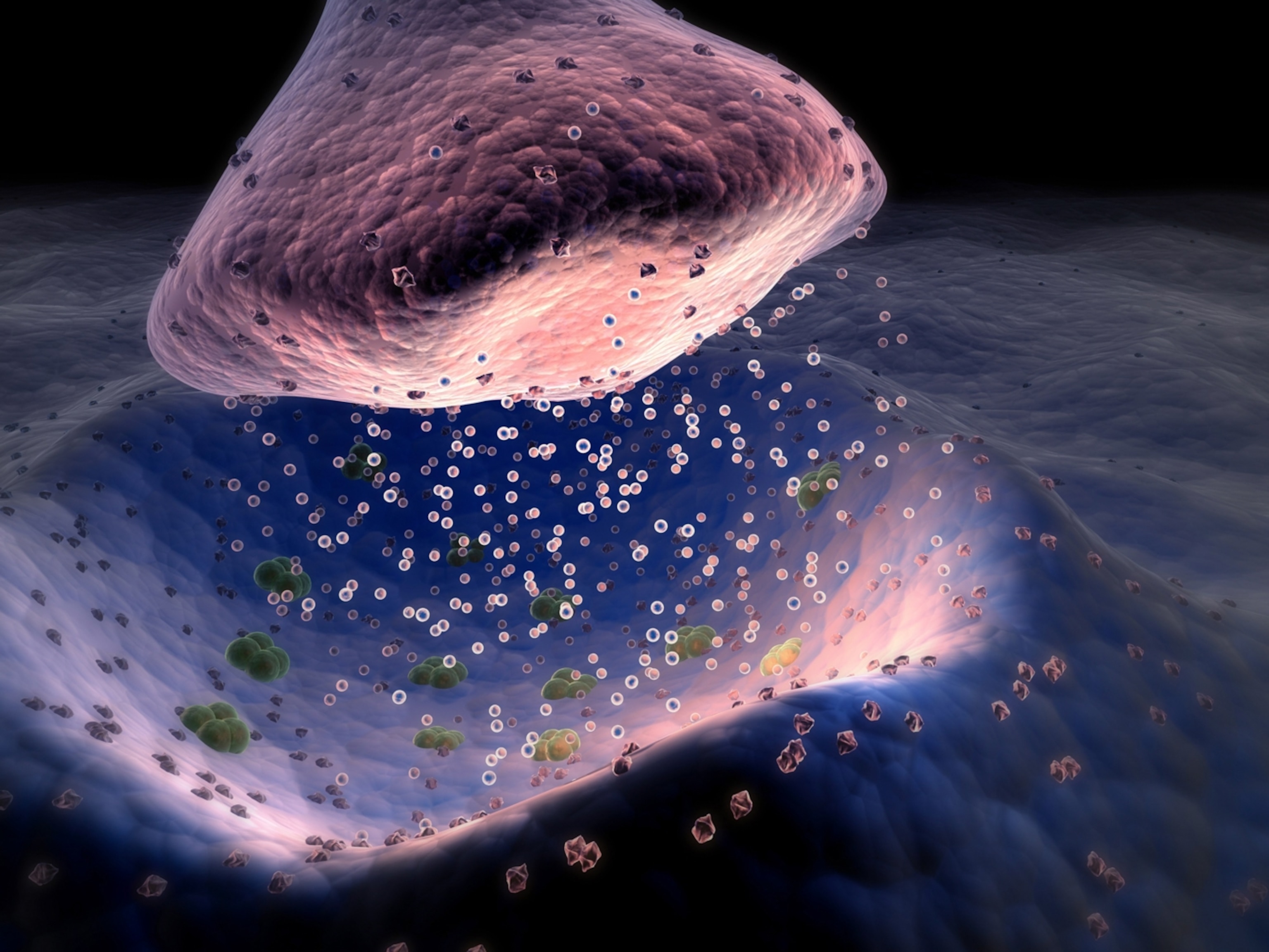

When we eat carbohydrates, our body breaks the food down into a kind of blood sugar called glucose. Our organs, tissues, and cells rely on glucose as a vital energy source, one of the reasons why the keto diet is so dangerous.

While there are many kinds of dietary sugar, nutritionists tend to break dietary sugar into two basic categories—regular, or natural sugar; and added sugar. (Learn how sugar and fat affect your brain.)

“Okay, so carrots are a vegetable. They are rich in beta carotene. But they actually have some natural sugar in them,” says Corkins.

Fruit has natural sugars, too, called fructose, as does milk, which contains a natural sugar called lactose. However, Corkins says that there is no limit to the amount of natural sugars kids should eat daily. Rather, it’s the added sugars we need to watch, as those can contribute to health conditions such as obesity, tooth decay, heart disease, high cholesterol, high blood pressure, type 2 diabetes, and fatty liver disease, according to the American Academy of Pediatrics.

In the United States, the leading sources of added sugars are processed desserts, sugar-sweetened beverages, and snacks, reports the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

For children under two, the American Academy of Pediatrics recommends no added sugars at all. Likewise, for children between two and age 18, the same experts suggest no more than 25 grams, or about six teaspoons of added sugar, each day.

To put those numbers into context, a single can of Coca-Cola contains 39 grams (or between 7.5 and 9.5 teaspoons) of sugar.

Sweet tooth

Now, before you start feeling like a bad parent for letting your kids have more sugar than the AAP recommends, rest assured that Corkins and his colleagues are aware of the enormity of this task.

“Most kids are getting more than that,” he admits.

Fortunately, U.S. food labels are now required to list “added sugars” as a separate category, which should make it easier for parents to identify hidden sugar in everything from sports drinks to breakfast bars. (Check out our hub on raising healthy kids.)

Overall, Schee advises parents to realize sugar is like any other ingredient—fine in moderation.

“Sugar itself isn't necessarily terrible if it's consumed in small quantities infrequently,” she says,.

“So I'm not really concerned about the occasional piece of birthday cake or the Thanksgiving pie. I'm more concerned about sugar in a kid's diet on a regular basis.”