Twins can become ‘unidentical’—and more fascinating twin facts

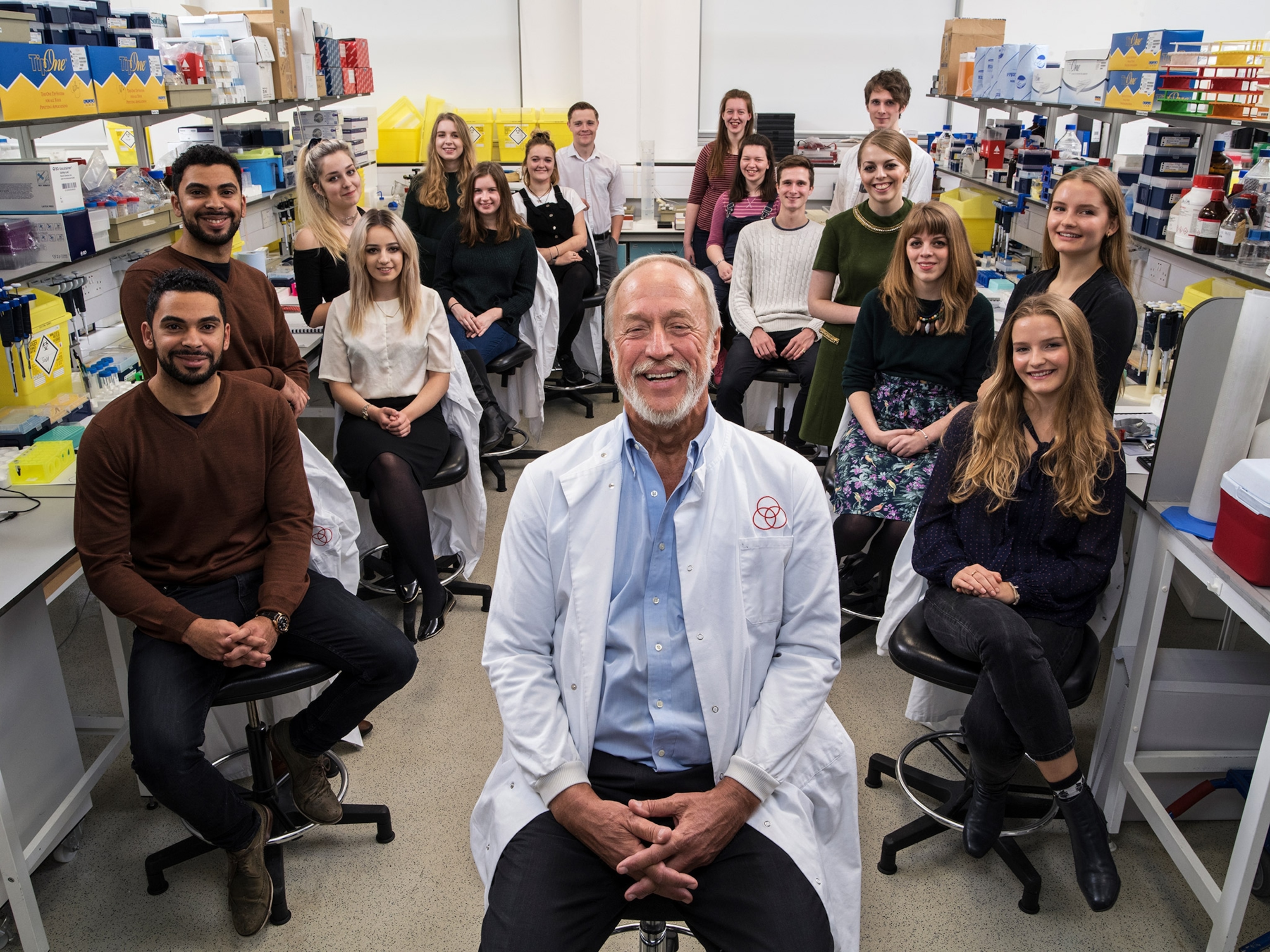

Looking into how twins’ genetics work can give researchers new insights into how different lifestyles and habits affect two people with the same genetic blueprint.

Each year, twin brothers and sisters from across the planet travel to Twinsburg, Ohio, to participate in the Twins Days Festival, taking place this year on August 4-6. It is the largest gathering of twins in the world, and it will get even larger if current trends prevail.

From about 1915 to 1980, one out of every 50 babies born in the United States was a twin. That number has since skyrocketed to one out of 30, and there’s no indication it is abating. Although still rare, the dramatic increase in twin births can mean more negative health consequences for mothers of twins and her children, including premature births and low birth weight.

But for geneticists, twin births are something to celebrate. Twins provide a trove of biological information that scientists cannot get anywhere else. They’re valuable in helping scientists understand diseases and other conditions, including eating disorders, obesity, sexual orientation, and various psychological traits.

Twin studies can also give researchers new insights into how different lifestyles and habits affect two people with the same genetic blueprint. Studying twins is extremely useful in examining the effects of genetic and environmental factors that can influence inherited traits across generations.

Nature versus nurture

That’s why twins often find themselves on the front lines of the nature-nurture debate. For decades people have argued about whether genes (nature) or the environment (nurture) have more of an impact on who we are. Twin studies give us a clue. Identical, or monozygotic, twins share 99.99 percent of their DNA. They look alike, or nearly alike. They have the same color eyes, the same color hair, the same everything—nearly. Fraternal, or dizygotic, twins share 50 percent of their genes. If identical twins share a trait to a greater degree than fraternal twins do, it’s safe to conclude that the relevant gene significantly influenced that trait. On the other hand, if both fraternal and identical twins share a trait equally, chances are their environment, not their genes, influenced that particular trait.

Identical twins can also help scientists determine how the environment impacts the way a gene functions, which in turn can help them figure out if certain traits or diseases rely more heavily on genetics or the environment. In 2015, the journal Nature Genetics conducted a comprehensive review of twin studies from across the globe. Researchers concluded that on average, environmental and genetic factors have an even chance of influencing a person’s traits and the diseases they might suffer from.

Twins no more?

Scott and Mark Kelly were once identical twin brothers. Then Scott Kelly spent a year in Earth’s orbit aboard the International Space Station and all that changed. When he landed, he was two inches (5 cm) taller, had a lot less body mass, and according to NASA researchers, aspects of his DNA had changed. He and his brother were no longer identical.

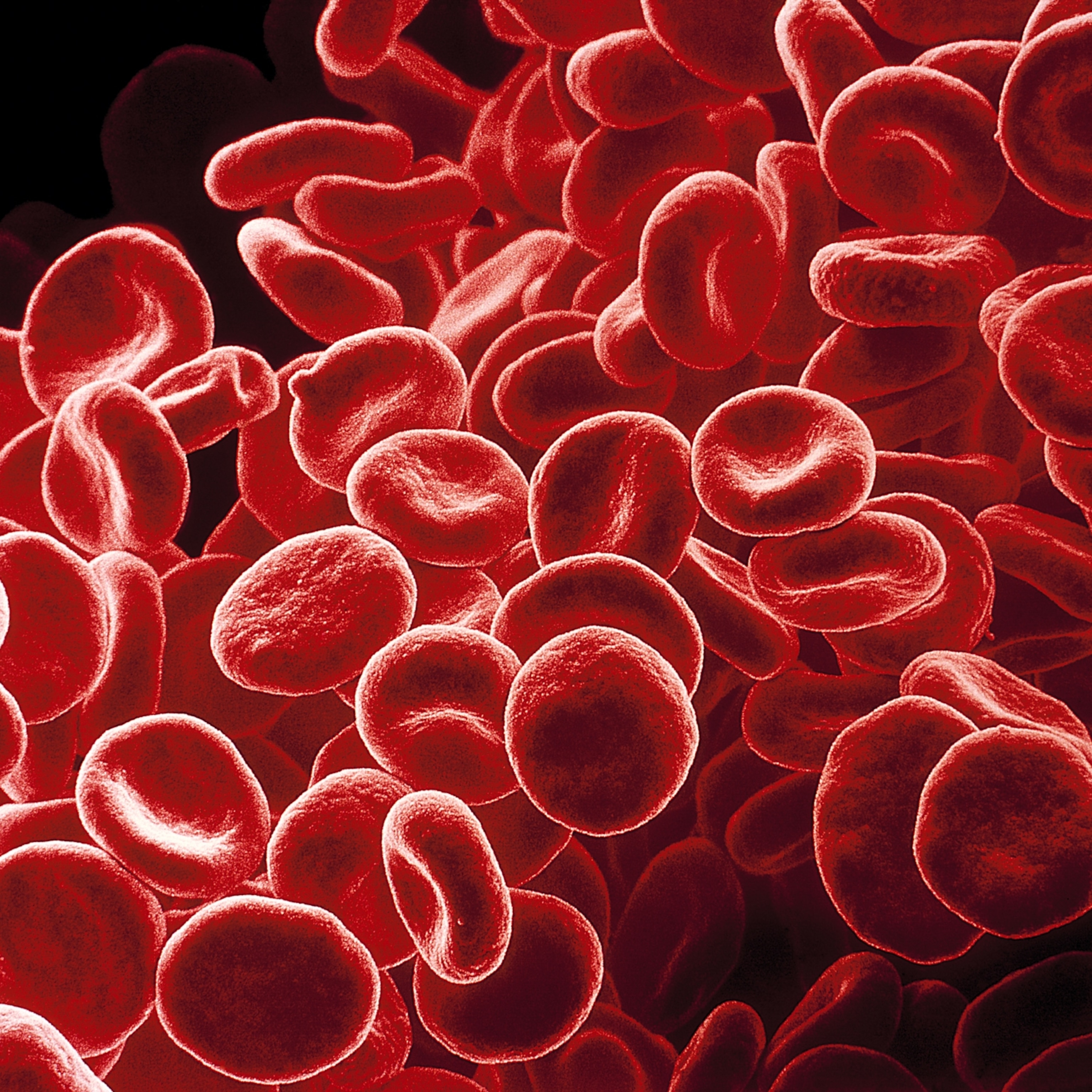

No, Scott didn’t turn into an extraterrestrial. Instead, the stress of living in space for so long had changed the way his genes worked—at least for a while. Since Scott and Mark share essentially the same DNA, scientists compared the men’s genes before and after Scott’s journey. Among other things, researchers wanted to know whether radiation would damage sections of DNA found at the end of every chromosome—so-called telomeres.

Telomeres are like the plastic tips at the ends of shoelaces that keep the fabric from coming apart. Without the protective coverings, the ends of the rod-shaped DNA can become damaged. Preliminary tests found Scott’s telomeres significantly increased in average length while in orbit, but shortened within 48 hours after landing. In contrast, his brother’s telomeres remained relatively stable.

Scott’s year in orbit also changed his immune system, the way his bones formed, and his eyesight, along with other biological functions. Most of those genetic changes returned to normal. However, researchers found 7 percent of his gene expressions had also changed. Gene expressions determine whether genes turn off and on, which can change how cells function. Scientists were not alarmed because environmental factors, in this case the stress of space travel, can affect this process. Consequently, Scott’s body quieted some genes while amplifying others.

Though his gene expressions changed, his DNA did not. Moreover, that Scott and Mark are no longer “identical” didn’t come as a surprise. At the most basic sequence level, chemical changes can occur over time, affecting where and how genes are expressed, even in identical earthbound twins. In reality, Mark and Scott Kelly haven’t been “identical” for years.

Sexual orientation

Studies of twins, both identical and fraternal, suggest that heredity is one of the major factors in determining a person’s sexual orientation. In fact, many studies say genetics swamps other influences such as parenting, education, and environment. Studies of male twins suggest that up to 60 percent of their sexual orientation is genetic.

Other studies have shown that identical twins are more likely to be attracted to those of the same sex than fraternal twins or nontwin brothers and sisters are. In one non-twin study, researchers looked at the genetic makeup of 456 men from 146 families with two or more gay brothers. Sixty percent of the gay men had the same genetic pattern on three specific chromosomes.

Research on twins can reveal a lot about how all humans work—not only in terms of gene function, but also that the concept of being gay may be no more a choice than being heterosexual.