This missing Wonder of the World inspired countless modern imitations

A gargantuan gold-and-ivory statue of the god Zeus—some 40 feet high—dazzled the ancient world when it was built in the 5th century B.C. After standing for 8 centuries, it disappeared, and its fate is still unknown.

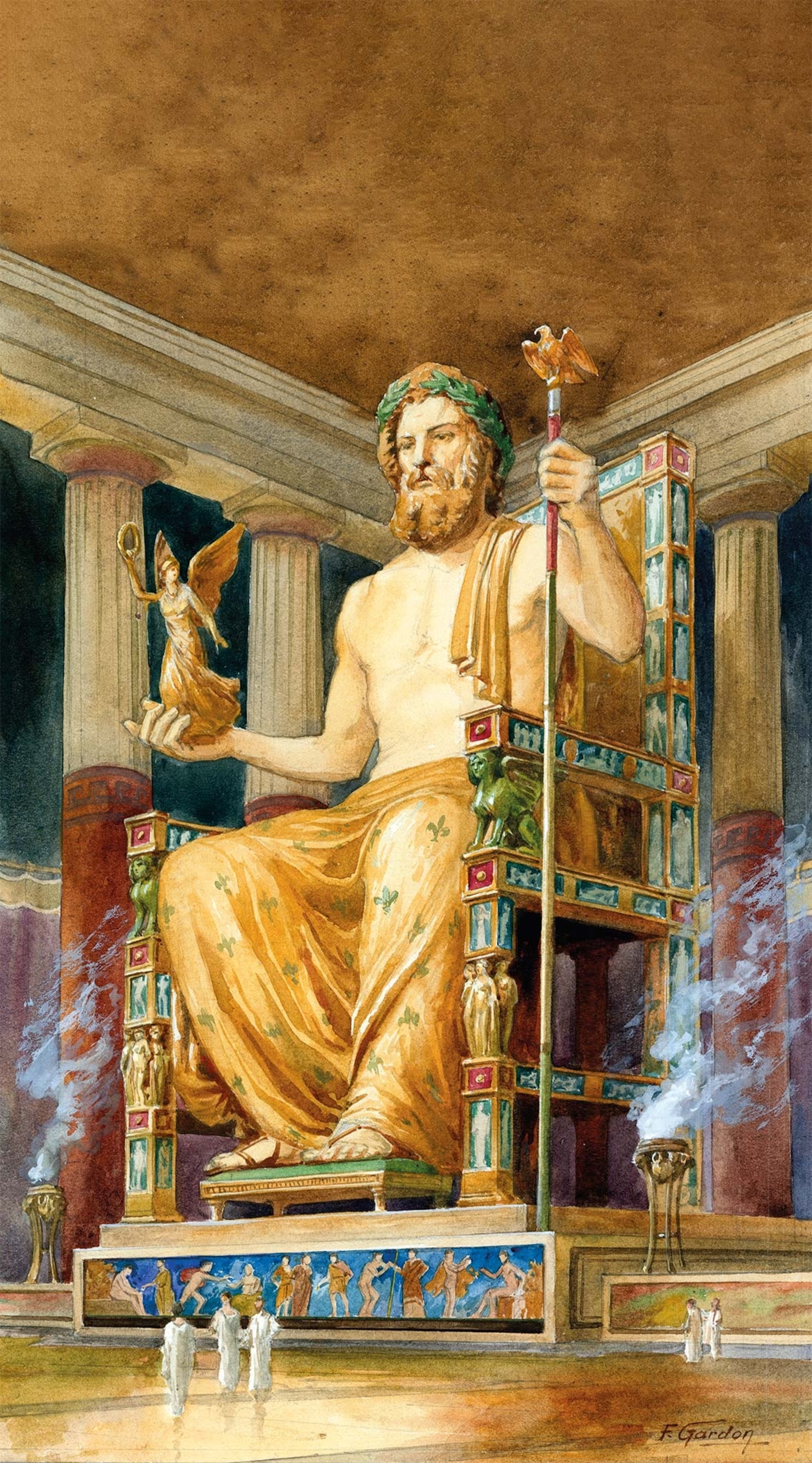

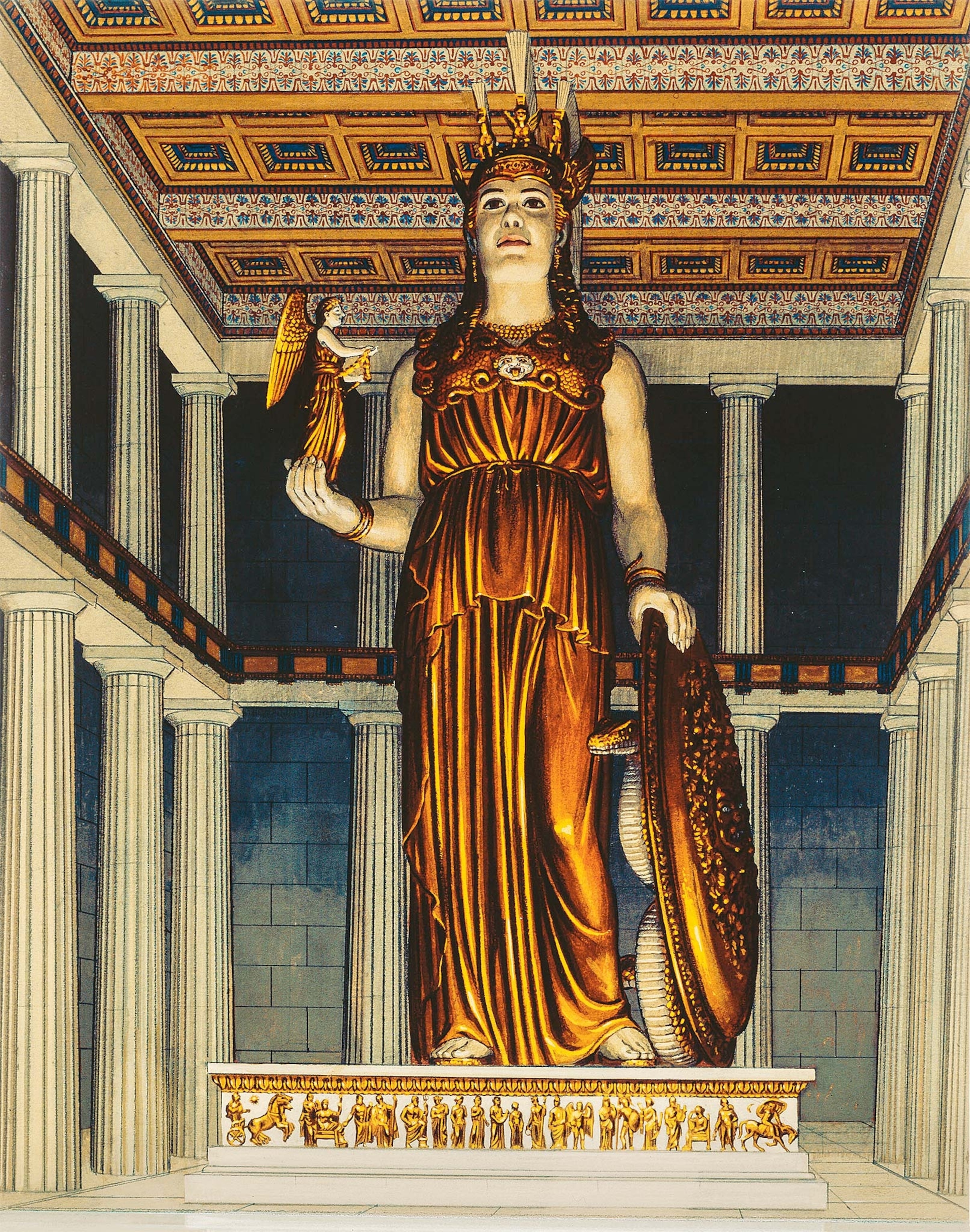

The statue of Zeus sitting on a magnificent throne rose about 40 feet inside his temple in the sanctuary of Olympia. It was so large that, according to the geographer Strabo, if Zeus stood up, his head would go through the roof. The lord of thunder was adorned in golden drapery. The craftsmanship was incredibly detailed, with intricate carvings and embellishments, including precious gemstones for his eyes. The work was so awesome that the Statue of Zeus was declared one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World in 225 B.C. by various observers, including the writer Antipater of Sidon and the mathematician Philo of Byzantium. The list also included the great Pyramid of Giza, the Hanging Gardens of Babylon, and the Lighthouse of Alexandria.

(We know where the 7 wonders of the ancient world are—except for one.)

Victory celebration

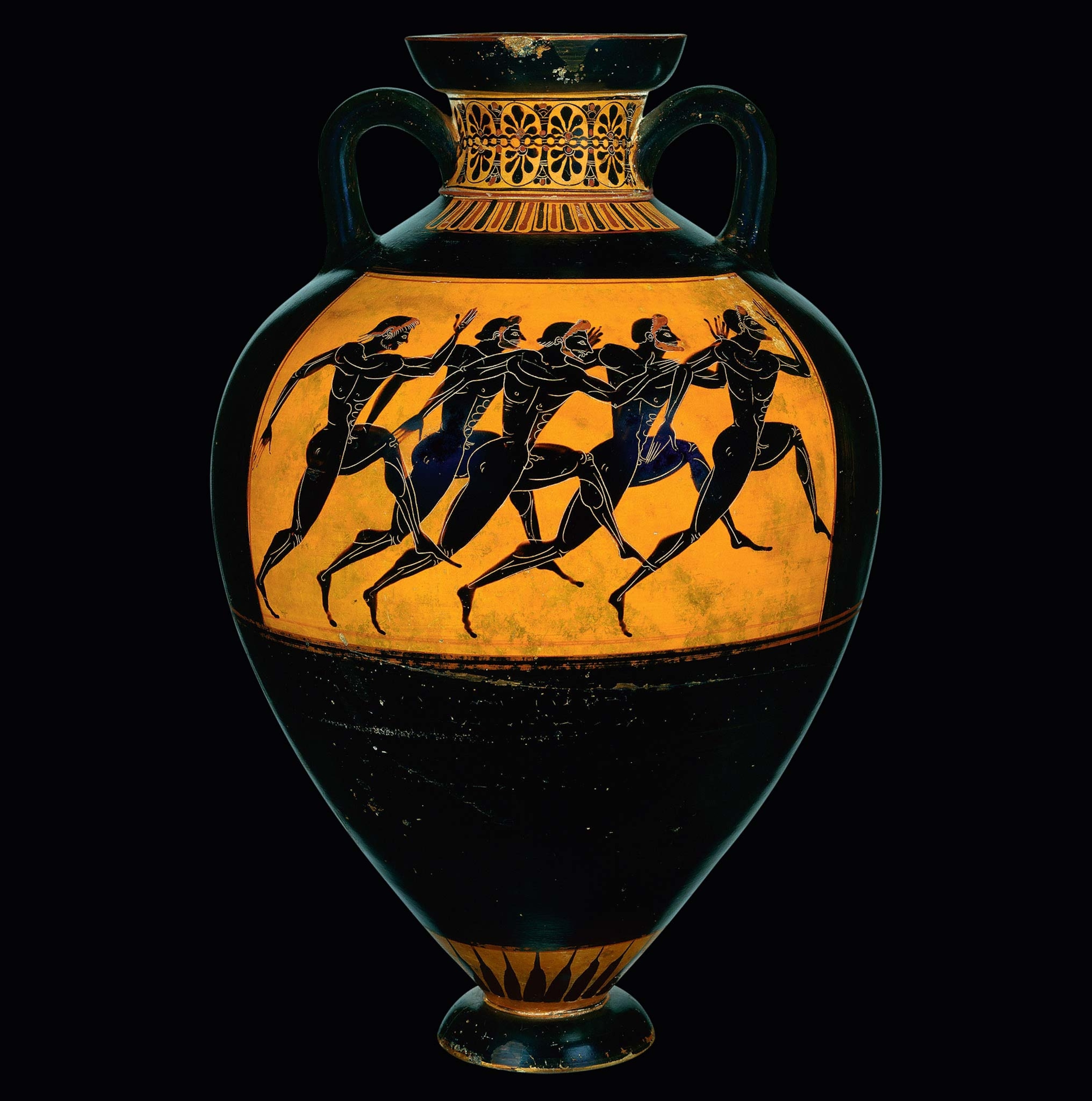

Long before the famous statue existed, the first Olympic Games, part of a festival honoring Zeus, were held in the Greek city-state of Elis in 776 B.C. In ancient Greece, Zeus was the supreme deity of the pantheon. He maintained order and harmony among the other gods, ensuring justice and overseeing the mortal world. Every four years, athletes and spectators from city-states across Greece pilgrimaged to Elis in an agreed-upon moment of harmony and peace to honor the gods.

That is, until the sixth century B.C., when both Elis and neighboring Pisa contended to control the games and all the political and economic benefits that came with it. Fierce battles and raids led to instability and disruption throughout the region until 464 B.C., when at long last Elis claimed victory. To celebrate its triumph, Elis embarked on the construction of a grand temple that would honor Zeus, using spoils won in the war.

(Ancient Greece’s Olympic champions were superstar athletes.)

Local architect Libon was chosen to build the temple in 460 B.C. A coat of fine white stucco was applied over the sturdy limestone base of the massive Doric temple. Six columns fronted the structure, with 13 running along the sides. A second floor wrapped around the central nave, accessed by stairs ascending from each side of the main door. Depicting myths and characters from Greek lore, sculptures decorated the temple. Many have survived and are on display in the National Archaeological Museum in Athens. Friezes of the chariot race between Pelops and Oenomaus were represented in the front gable, and the battle of the Lapiths and the Centaurs at the wedding of Pirithous decorated the back gable. Metopes depicted the 12 labors of Hercules. All are masterful works of classical sculpture, though their artist remains unknown. But the pièce de résistance appeared inside the temple itself.

Master sculptor

Phidias, a well-known artist and architect of the time, was commissioned to make the temple’s most important work: a giant statue of Zeus enthroned. Details of Phidias’s early life are few. Born in Athens around 500 B.C., he likely fought in the battle of Salamis or Plataea against the Persians. His military service gained the favor of Cimon, a wealthy Athenian politician and military man who chose Phidias to build the memorial for the victory of Marathon at Delphi.

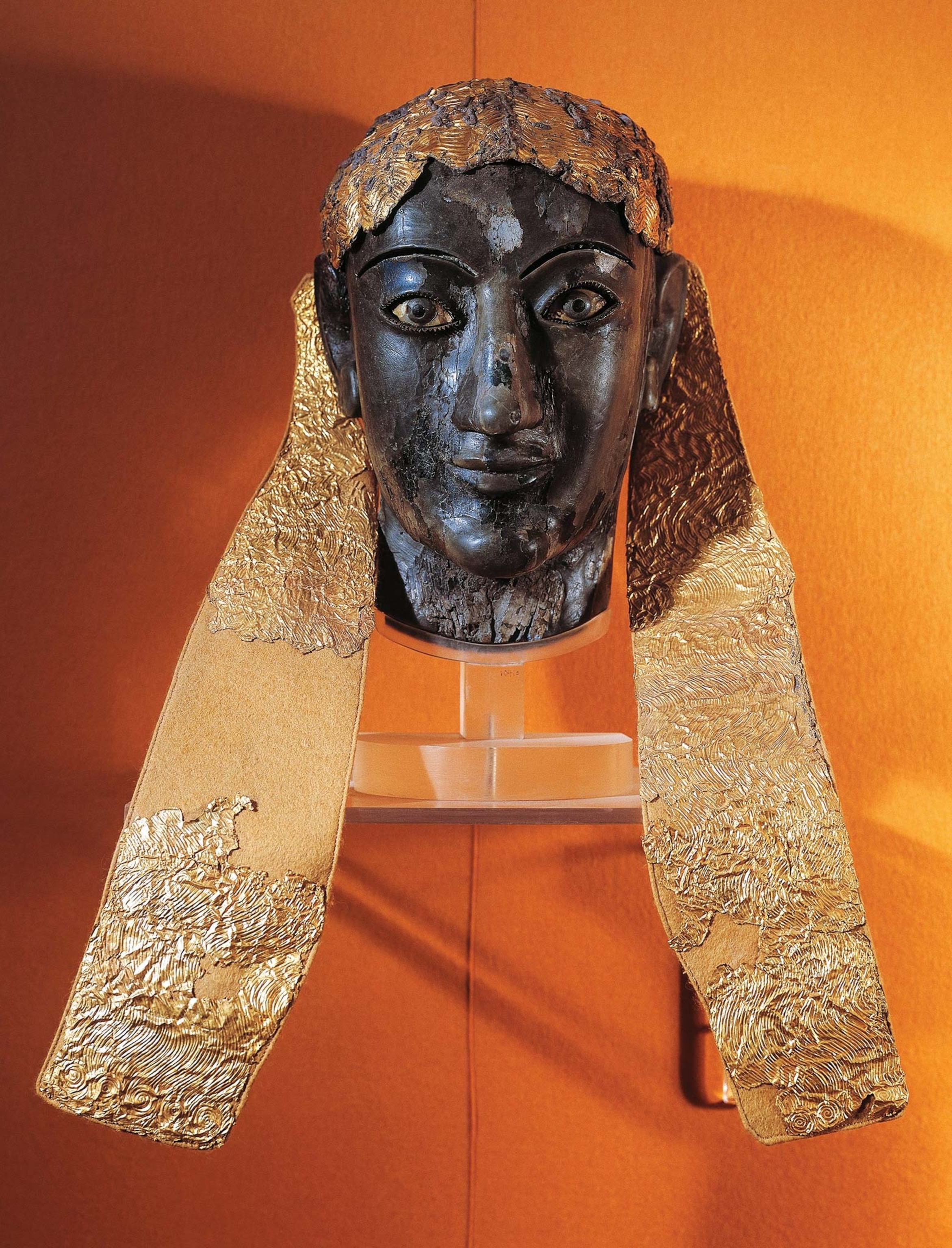

Phidias’s reputation spread throughout Greece, and he was awarded many projects before his commission at Olympia. His grand plans for Zeus relied on a technique known as chryselephantine, in which smooth ivory and glistening gold are placed over wood. Phidias was famous for designing colossal figures using the application; among his most celebrated, created at around the same time as the Zeus statue, was the towering sculpture dedicated to Athena in the Parthenon of Athens.

Greek artisans typically worked ivory on a small scale. Ivory is a difficult material to manipulate. Unrolling the different layers of dentin that compose an elephant’s tusk to mold the resulting material requires skill and expertise. Exactly which technique Phidias used to manipulate the ivory plates on such an ambitious scale is uncertain. Writing in the second century A.D. the Greek geographer Pausanias says that Phidias applied heat to the ivory to soften it. Other sources claim he moistened the ivory, perhaps with vinegar or beer, before working with it.

(See the myth of Hercules carved into this ancient sarcophagus.)

Putting it together

Phidias’s Olympia workshop, divided into three naves by two rows of columns, had the same dimensions as the cella in the Temple of Zeus, where the sculpture would be housed. In this way, the correct proportions were ensured.

Phidias meticulously sculpted the details of Zeus’s face, body, and other features, refining his expression, hair, beard, and drapery to bring the statue to life. Various materials, including precious stones and colored glass, were used to enhance the statue. When it was complete, the statue would have been polished to a smooth and lustrous finish, allowing the gold and ivory to shine brilliantly.

While some details of construction were recorded, the statue’s exact height is unknown. Historical accounts, such as geographer Strabo’s in the first century B.C., recorded the statue’s hulking first impression. Strabo wrote: “If Zeus arose and stood erect, he would unroof the temple.” Modern scholars, based on archaeology and inference, believe it stood about 40 feet high. Its stone base, measuring some 20 by 32 feet, was made of black Eleusinian marble.

When it was finished, the statue was resplendent. Pausanias’s Description of Greece contains a glowing description:

The god sits on a throne, and he is made of gold and ivory. On his head lies a garland which is a copy of olive shoots. In his right hand he carries a Victory, which, like the statue, is made of ivory and gold; she wears a ribbon and—on her head—a garland. In the left hand of the god is a scepter, ornamented with every kind of metal, and the bird sitting on the scepter is the eagle. The god’s sandals are also made of gold, as is his robe. On his robe are carved figures of animals and the flowers of the lily.

The seat of power

Appearance of a god

Pausanias also reported how the statue was anointed with olive oil, which also served to protect the ivory exterior and the wooden interior. Around the base of the statue, a raised lip allowed the oil to collect around the base of the statue and form a pool. The statue’s reflection in the liquid made it seem all the larger.

Pausanias’s account reveals how impressive the Statue of Zeus might have been to behold in person, but scholars are still pondering how it was viewed inside the temple. The statue’s white ivory and sparkling gold would hardly seem as magnificent in a darkened chamber. Symbolically a god’s house, Greek temples were open spaces, but the interior needed light during the day. How was the room lit?

(Dionysus, Greek god of wine and revelry, was more than just a 'party god'.)

Countless solutions have been proposed to explain how the statue was illuminated. It is difficult to imagine artificial light, such as lamps, candles, or torches, as the main source, since such an enormous number of them would have been necessary to light such a large space. It has also been suggested that open skylights might have graced the roof, but this solution would have left the interior exposed to weather and rain.

The Zeus statue presented another issue. Because of its size, the upper portion rose above the level of the entranceway, so direct light from the doorway could not shine up-on Zeus’s head. Moreover, light would have entered the door only at sunrise. By midday, the sun would have been too high for rays to directly light the cella.

Recent studies with ultraviolet lights and lasers have shown that thin translucent marble tiles on the roof, placed on a wooden frame, may have allowed dim but constant sunlight to enter throughout the day. This solution would have offered enough light to showcase the temple’s interior and statue while still protecting them from the elements.

(Visit the islands where most Greek marble statues were made.)

Lost wonder

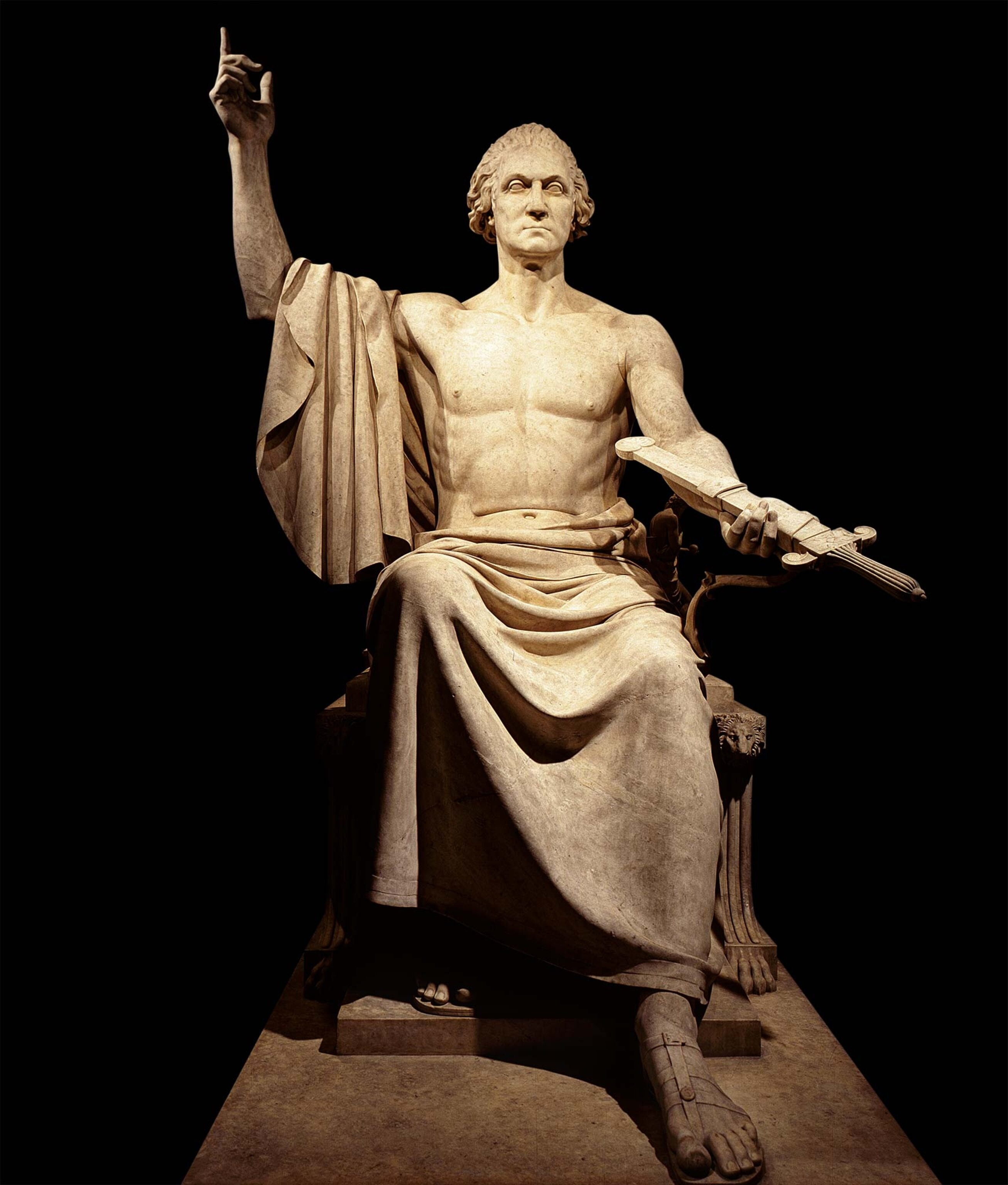

With the completion of the temple and its magnificent statue, the previously small sanctuary at Elis became one of the most important religious centers in ancient Greece. Appearing on coins across the ancient world, the monumental Zeus reigned as one of the most famous statues in antiquity and became the main sculptural model for seated gods. (Artists working millennia later would continue to imitate Zeus’s pose and gestures in many works of art.)

Visitors from all over the ancient world came to Olympia for not only the games but also the craftsmanship and ambition embodied by the Statue of Zeus. Sometime between the second and first centuries B.C., writers began compiling lists of must-see sights around the Mediterranean. The Statue of Zeus at Olympia was one of these seven ancient wonders listed by writers such as Herodotus, Antipater of Sidon, and Philo of Byzantium.

The statue’s popularity continued well into Roman times. The spread of Christianity in the fourth century A.D. became its biggest threat. Roman emperor Theodosius I outlawed pagan cults in 391 A.D., ordering all ancient sanctuaries to be abandoned—including Olympia’s. He also banned the Olympic Games, since it was a polytheistic festival. The sanctuary at Olympia fell into disuse and eventually into ruin.

The statue, however, met a different fate. Aeunuch in Theodosius II’s court had it moved to Constantinople (modern-day Istanbul), then the capital of the Eastern Roman Empire. The Statue of Zeus was kept in the collection of “pagan antiquities” in the Palace of Lausus.

From then, the statue’s ultimate fate is unknown. Conflicting reports say it was destroyed by fire or perhaps lost in an earthquake. But by the end of the fifth century, the Statue of Zeus was no more. After 800 years of existence, Phidias’s prodigious sculpture perished, but it has not been forgotten.