Dramatic Pictures of Recent Sinkholes Reveal Hazards Lurking Below

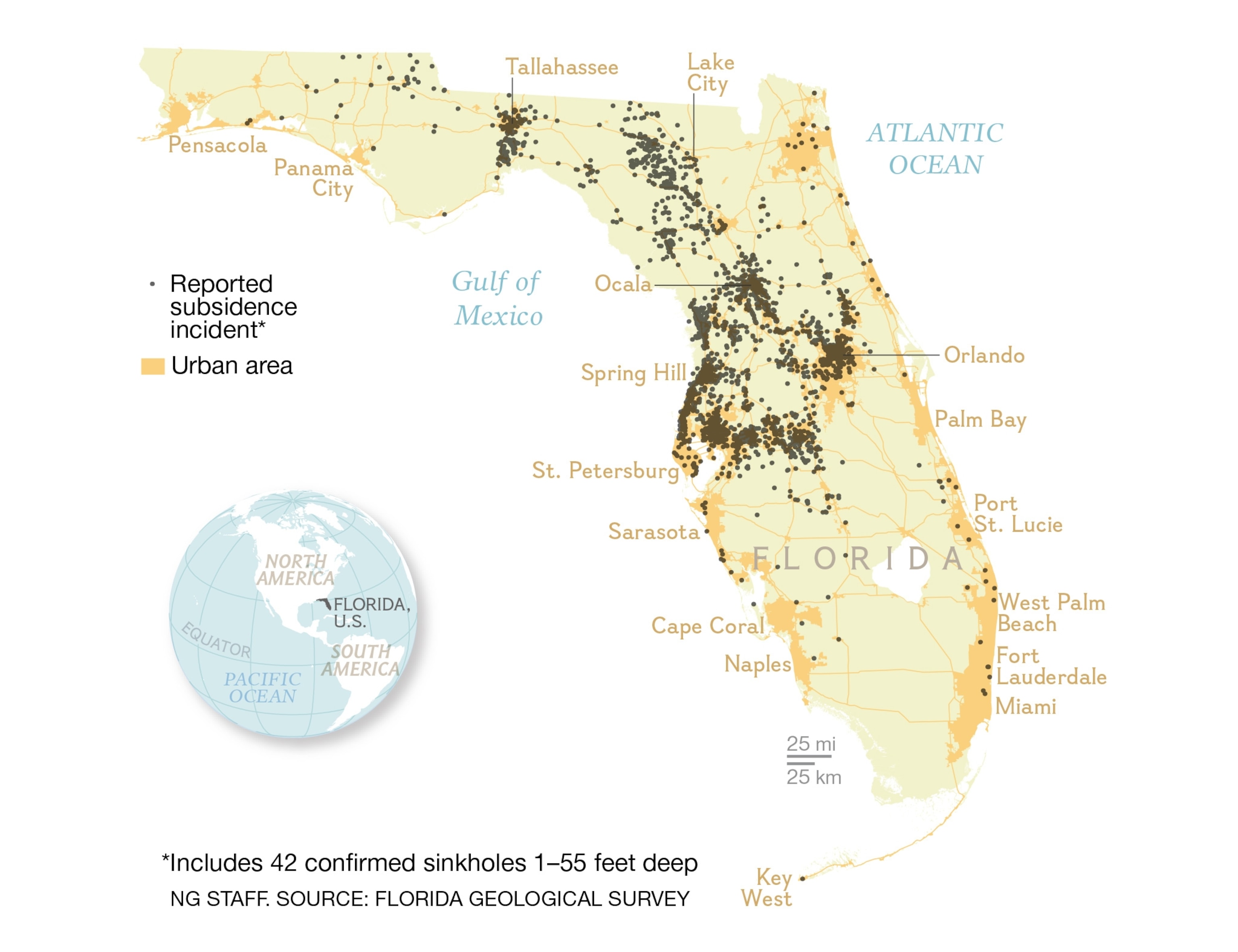

Natural and human-caused sinkholes have swallowed cars and houses in Florida, Minnesota, England, China, Latin America, and beyond.

Last Saturday, a massive sinkhole swallowed part of a residential neighborhood in Spring Hill, Florida, about 45 miles (72 kilometers) north of Tampa. No one was injured, but a pair of houses suffered damage, and four families had to evacuate.

The circular sinkhole is about 40 yards (37 meters) across and 30 feet (9 meters) deep, says Virginia Singer, a spokesperson for the local Hernando County government.

"No one thing in particular triggered the sinkhole that we are aware of," she says. "It's an occurrence that happens in this part of Florida."

Nearly 300 sinkholes have opened up in the Sunshine State since 2010 and thousands over the past century.

Denise Moloney, a spokesperson with the Hernando County Sheriff's Office, says her department advises residents to be on the lookout for signs of potential sinkholes, such as cracks or slumping.

But sometimes there are no warnings, she says, and sometimes what seem like signs aren't. "Just because you have a crack in your house doesn't mean your house is going to fall into a sinkhole," she says. "That's very rare."

Coastal western Florida is especially prone to sinkholes because its soil doesn't contain a lot of clay, which can help hold the layers together, says Clint Kromhout, a geologist with the Florida Department of Environmental Protection. Instead, the area tends to have sandy soil on top of limestone.

When groundwater dissolves some of the limestone, it creates caves. Eventually the overlying sandy layers may no longer be able to support their own weight, says Kromhout, and they collapse, forming a sinkhole. (See "Why Sinkholes Open Up.")

The sinkhole above opened up in June 2012 in a parking lot in Salt Springs, Florida, which is also in the Tampa Bay region. Tropical Storm Debby had pelted the area with up to two feet of rain in a few days.

Clint Kromhout says heavy rains tend to make sinkholes more likely, because they can destabilize soil, leading to its collapse.

He adds that sinkholes sometimes leave clues as they're forming. "Look for dying patches of grass or shrubs that may suggest the water table has suddenly gone down," he says. Tilting trees or fence posts, new cracks in sidewalks or foundations, and doors or windows that don't shut properly can also be signs.

"It needs to be a collection of things, not just one thing," says Kromhout. "And if those things start to accelerate, then it's time to think about calling your insurance." Insurance companies can send inspectors who have experience with what are called subsidence events. Only a geologist can decide whether a particular subsidence is a true sinkhole.

A sinkhole that opened in Clermont, Florida, in August 2013 damaged three buildings at the Summer Bay Resort northeast of Tampa. The hole was 40 to 50 feet (12 to 15 meters) in diameter.

According to Kromhout, there are two types of sinkholes: cover-subsidence sinkholes and cover-collapse sinkholes. The former develop slowly over time, but the latter open up quickly and can take buildings, and occasionally people, with them.

Sinkholes are prevalent in Florida thanks to its sandy soil and underlying limestone, but they also occur in many other places around the world. Above, a 30-foot-deep (9-meter-deep) sinkhole opened up in a driveway in Buckinghamshire in the U.K. in February 2014. The hole swallowed a car. (See: "Guatemala Sinkhole Adds to World's Famous Pits.")

In February 2014, a sinkhole in Bowling Green, Kentucky, swallowed eight Corvettes at the National Corvette Museum.

Photographer Alex Slitz described the cars as flung into the earth as if they were toys.

In February 2007, a 330-foot-deep (100-meter-deep) sinkhole opened up in Guatemala City, killing three people and swallowing about a dozen homes. Deeper than the height of the Statue of Liberty, the hole was reportedly caused by torrential rains and a burst sewer line.

According to Kromhout, burst pipes aren't the only human activity that can lead to sinkholes. Overpumping of groundwater can also destabilize soil, as can earthmoving activities.

And paving over ground can cause runoff to concentrate in specific areas, where it can destabilize the surface. (See "2010 Guatemala Sinkholes Created by Humans, Not Nature.")

A tourist visits a picturesque sinkhole on Mount Roraima, in Venezuela's Canaima National Park.

In time, sinkholes often become ponds. Eventually they may fill in with soil and debris.

Sinkholes in bedrock limestone around the Yucatán Peninsula are often called cenotes. The Maya considered them sacred places, and several have become important archaeological sites. (See: photos of cenotes.)

Above, a diver explores a cenote near Akumal, Mexico, in 2009.

As the Dead Sea in Israel and Jordan continues to recede, thanks to diversion of the Jordan River, the water table below is also dropping. This has caused numerous sinkholes to open up in the land, and much of the area is now off-limits to visitors.

China has extensive karst zones, where soluble rock below the surface has been dissolved by water, creating a network of fissures and caves. This massive sinkhole opened up in the village of Pingxi in southwest Sichuan Province in December 2013.

Within hours, the hole expanded into a crater measuring 200 feet by 130 feet (60 by 40 meters) and 100 feet (30 meters) deep that swallowed about a dozen buildings.

In June 2012, a sinkhole opened up in Duluth, Minnesota, after a torrential rainstorm.