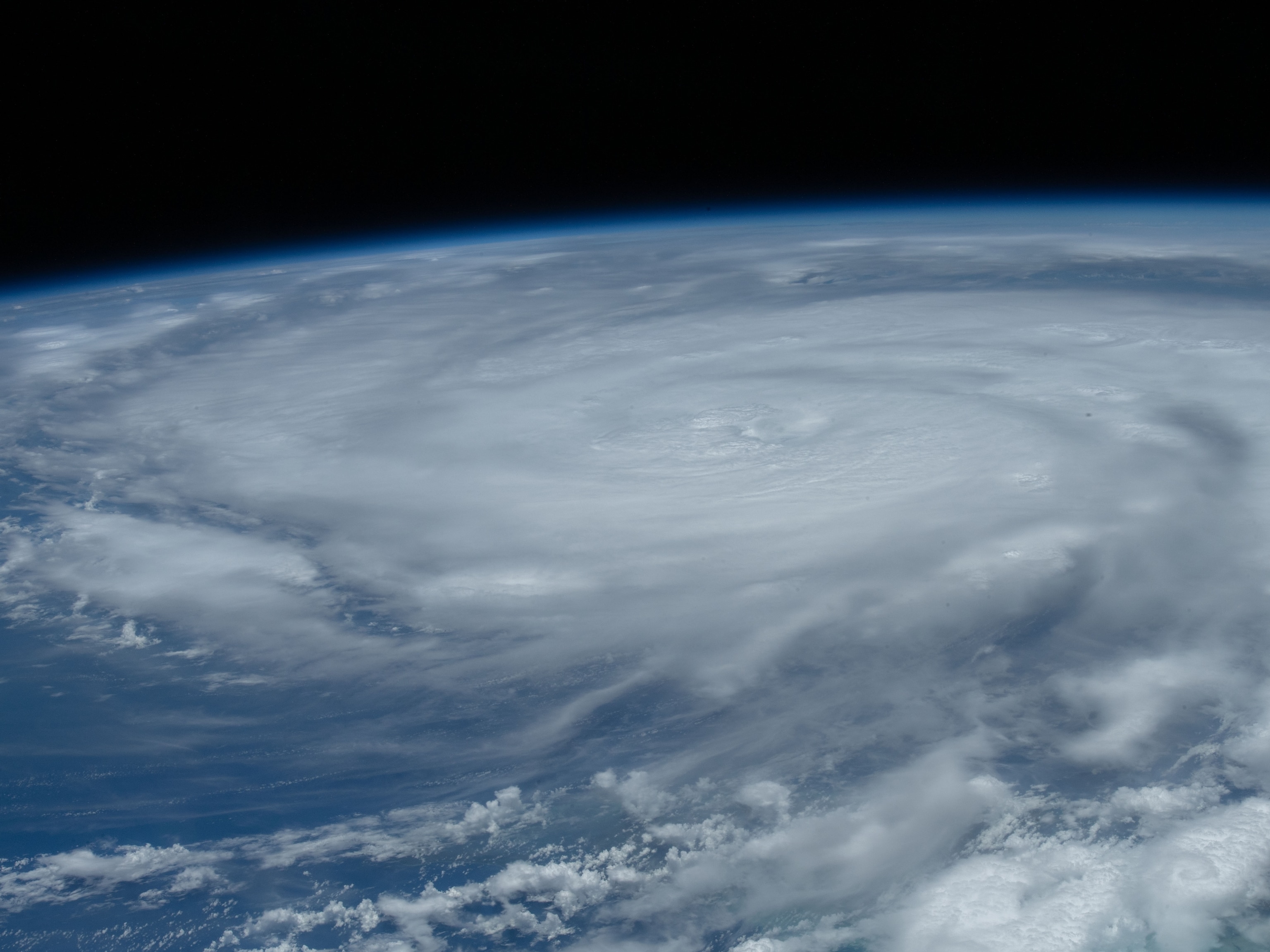

Charts Show How Hurricane Katrina Changed New Orleans

Hurricane Katrina had lasting effects on the physical and social makeup of the Big Easy.

Since Hurricane Katrina struck New Orleans ten years ago, data has played a central role in tracking how the city has transformed.

The storm greatly changed the physical and demographic makeup of New Orleans. Monitoring these changes is important, since the needs of the city and it’s people are much different today. “After any disaster, applicable data is wiped away—all information becomes uncertain,” says Allison Plyer of The Data Center, a data collection and analysis group that serves Southeast Louisiana.

What major trends can data reveal about how current New Orleans compares to pre-Katrina New Orleans? Many of the changes are notable: The traditional school system was overhauled; some neighborhoods are still relatively empty; demographics have shifted; and startup businesses are rampant.

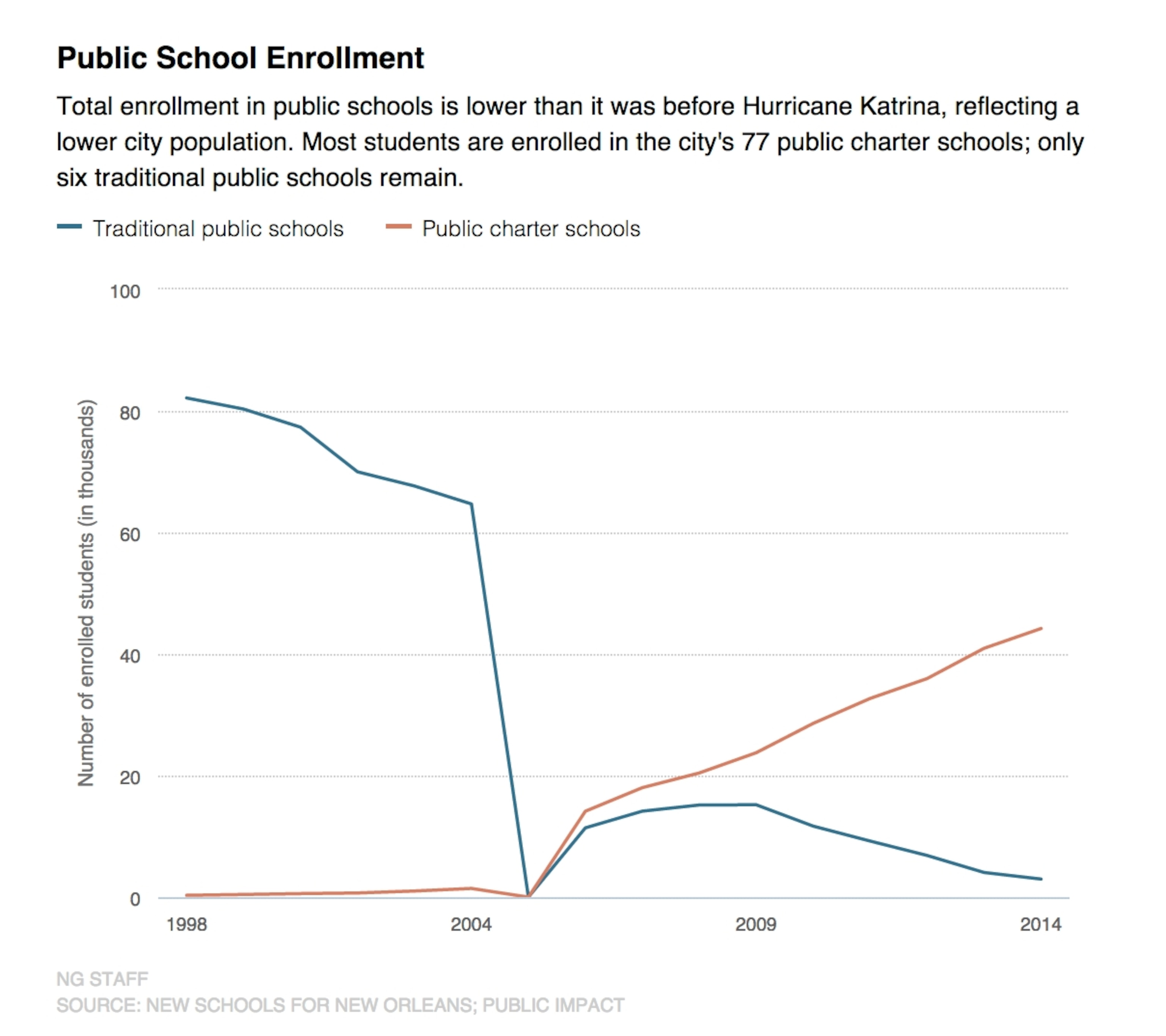

Schools

The New Orleans public school system is arguably the single-most transformed institution in the city. Since Katrina, most public schools have become public charter schools, which are independently run.

With a higher proportion of students enrolled in charter schools than anywhere else in the country, New Orleans is the first public education system made up mostly of charters. Today, nearly 95 percent of students attend public charter schools. Less than five percent did before Katrina.

Katrina certainly accelerated this switch, but the legislation that enabled it to happen was passed in 2003. Known as Recovery School District legislation, the law let the state turn failing schools into public charters. After Katrina, the state expanded its definition of failing, allowing it to take over even more schools. Katrina provided something of a blank slate to reopen schools as charters.

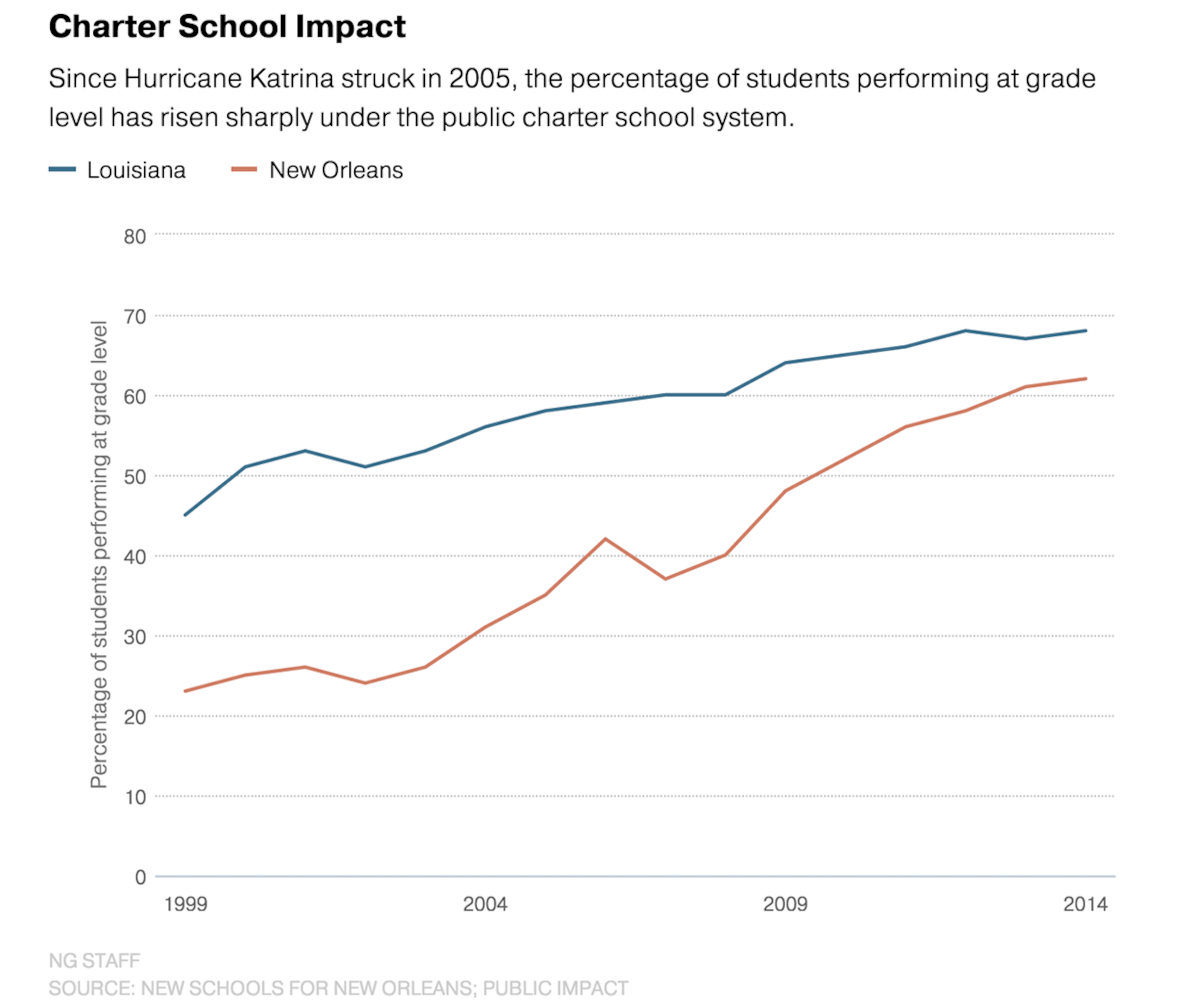

Has the move to public charter schools been successful? New Orleans parish went from being one of the worst school districts in the state to nearly on par with the state average. Charters have been instrumental in closing the achievement gap: 62 percent of students are now performing at their grade level versus only 20 percent 15 years ago.

For Michael Stone, co-CEO of New Schools for New Orleans, the success of charters is tied to a new governance system. “The state and local government aren’t involved in the day-to-day operations of schools, so principals and teachers have the autonomy to make quick decisions,” Stone explains. That’s helped schools respond faster to students’ needs.

In many ways, the move to public charter schools has been beneficial, but it’s not without critics: Some dislike how far children have to travel to school, since neighborhood schools no longer exist. Others find the application process too complicated. And, the rankings are still relative: New Orleans moved up from the second-worst school system in the state to match the state average, but Louisiana still has one of the lowest ranked school systems in the country.

Population Recovery

Postal data has been a useful population indicator for the city, since the U.S. Census only does robust population estimates every 10 years. In the last five years, the number of households receiving mail in New Orleans increased by nearly 20,000, and 65 neighborhoods have shown gains. (If mail has been picked up in the previous 90 days, the U.S. Postal Service deems the house as actively receiving mail.)

More than half of the city’s 72 neighborhoods have recovered 90 percent of their pre-Katrina population, and 16 neighborhoods have actually gained population since the storm. According the U.S. Census Bureau, New Orleans grew by 12 percent between 2010 and 2014.

But not all neighborhoods have repopulated equally. For example, St. Thomas Development, located in the southern part of the city along the Mississippi River, rebounded by 300 percent, while Iberville Development, near the French Quarter and Central Business District, is virtually empty with only .1 percent of its pre-Katrina households. That’s largely because St. Thomas was being redeveloped with new public housing before the storm struck, so it started off from a low-point, versus Iberville, which was fully occupied and then wiped out. Future plans call for redeveloping Iberville with public housing.

Nearly all of the neighborhoods along the Mississippi River, known as the “sliver by the river,” have gained households since 2010, with the Central Business District alone adding over 1,300 homes. These areas recovered quickly, since they experienced very little flooding. The neighborhoods along the river sit above sea level, a result of flooding that built up the riverbeds, explains Plyer with The Data Center.

Demographic Shifts

The demographic makeup of New Orleans and its metro area is much different today than it was pre-Katrina. The city has lost white and black residents, but whites now represent a larger share of the population than they did before the storm. And while African Americans are still the majority in New Orleans, their raw population drop is staggering: Nearly 100,000 fewer African Americans live in the city today than in 2000. Around 11,500 fewer white residents live there.

One major change has been the rise in the Hispanic population. In New Orleans, the share of the Hispanic population rose by over 2 percent, or more than 6,000 people. Many of the new residents came seeking jobs rebuilding New Orleans. The damage was so extensive that the federal government suspended many labor regulations in order to speed up recovery. Many people decided to stay, since they found long-term work.

The New Orleans metro area’s Hispanic and Asian populations have grown, a change that tracks with the national trend.

Startup Culture

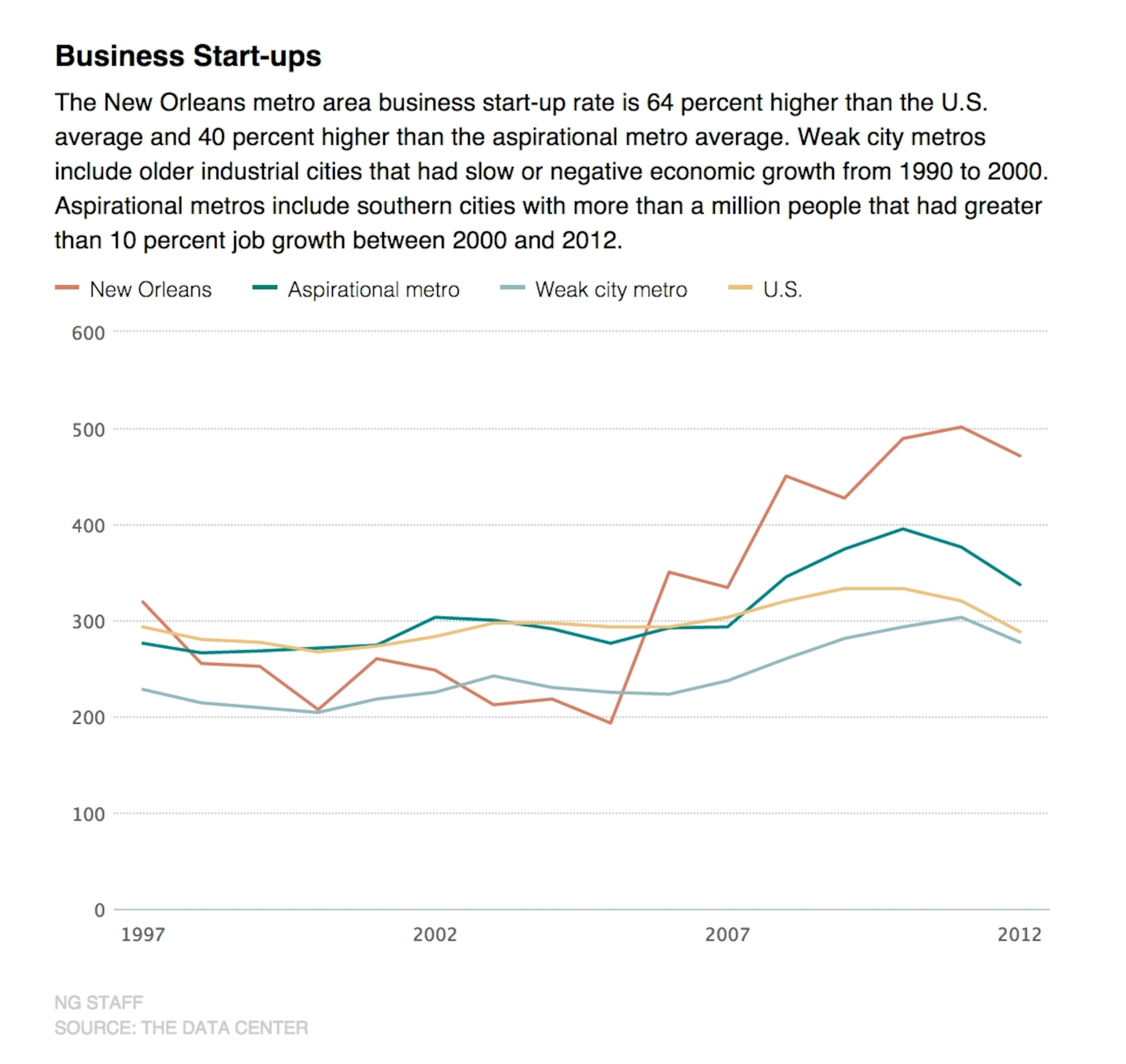

One interesting economic outcome of Katrina has been the boom in startup businesses. The number of new businesses spiked after the storm, as entrepreneurs provided services such as debris removal and construction. But the fact that ten years after the storm the startup rate is 64 percent higher than the national average says a lot about New Orleans’ business climate.

“There’s a lot of energy in New Orleans right now,” says The Data Center’s Plyer. Many of these new companies fall into the social entrepreneurship category. They’re responding to needs for everything from new technologies for helping charter school teachers to innovative ways of dealing with blighted properties. “Katrina captured the nation’s interest and many people really want to contribute to the city’s recovery,” she says.

Follow Kelsey Nowakowski on Twitter.