Biodegradable plastic exists—but it’s not cheap

Several new projects turn waste into food for microbes that create PHA, a type of plastic that fully decomposes on its own, offering a less costly alternative to current bioplastics.

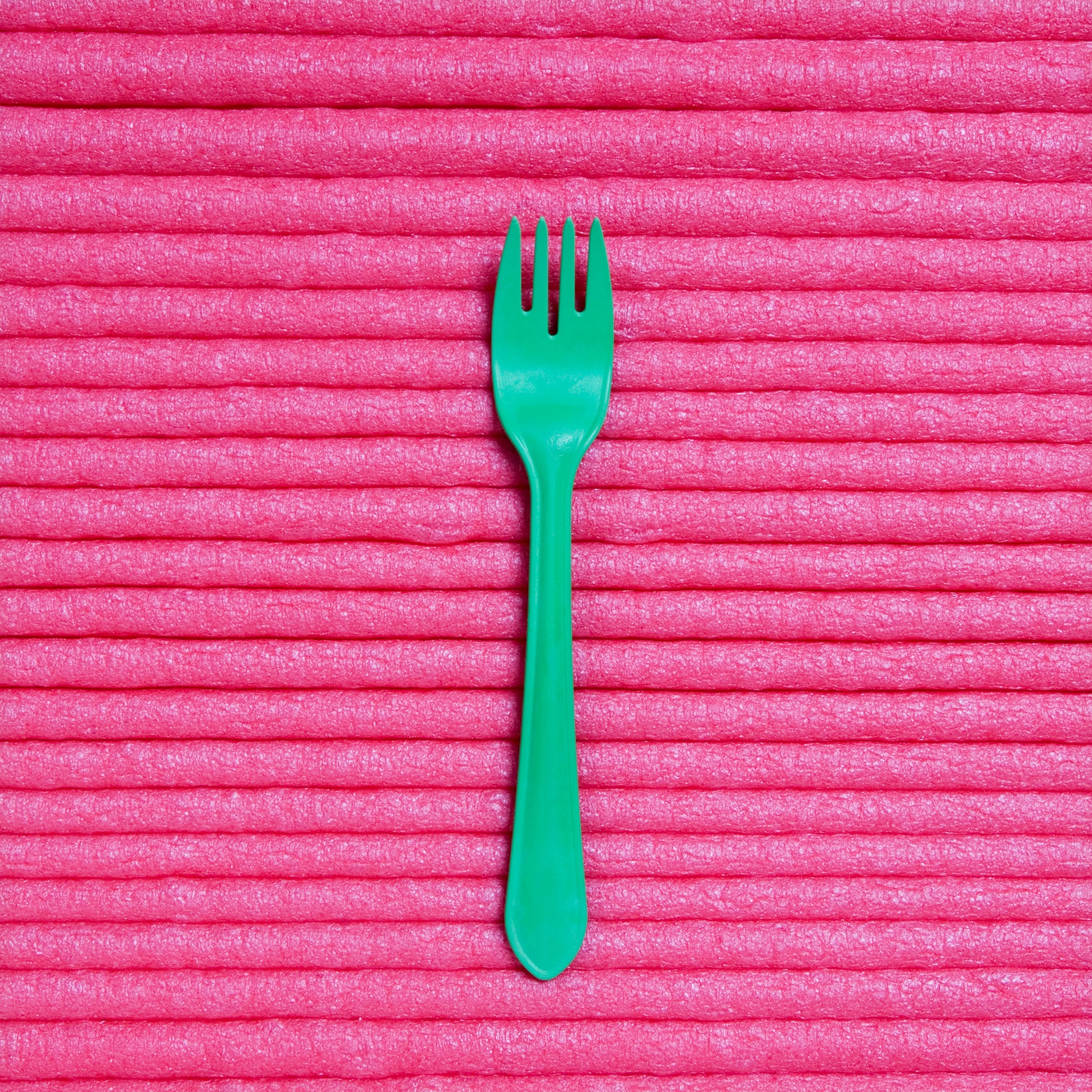

From cellphone cases made of starch to diapers that compost in soil, products made from bioplastics are more accessible than ever. You can already find bioplastics in disposable forks at Whole Foods, Philz Coffee cups, and even in packing peanuts.

These plastic alternatives are manufactured much the same way as fossil-based conventional plastics, however, the primary distinction lies in the source of the raw materials. Bioplastics are manufactured from renewable resources like vegetable oils, sawdust, and food waste. Bioplastics generally have a lower carbon footprint because several types have the ability to degrade completely either on their own or with industrial treatment, according to a paper set to be released next month.

But bioplastics, often called bio-based plastics, are not all equally biodegradable. Bio-based plastics like PET (polyethylene terephthalate), for example, are sometimes recyclable but not biodegradable. The production of bioplastics also produces varied carbon footprints—sometimes producing significantly more than the production of traditional plastics.

Two of the most common biodegradable bioplastics are PHAs (polyhydroxyalkanoates), which are biodegradable, and PLAs (polylactic acid) which are much more commonly used but are only compostable on an industrial scale.

The bioplastic industry is growing rapidly, expected to hit a value of $57 billion by 2032, according to one research firm. Though progress is being made, bioplastics are still three to four times more expensive to make than traditional plastics.

That’s why researchers are using new technologies—like repurposing the technology used to treat wastewater—and new materials like cheese discard to make bioplastics cheaper.

Biodegradable plastic made from food waste

Bacteria like the species Cupriavidus necator synthesize PHA, a bioplastic that’s totally biodegradable, all on their own. To make PHA, scientists keep these microorganisms fat and happy with “feedstock”—usually some type of sugar like corn starch—so that they multiply and start producing PHA. That feedstock ends up accounting for a large part of production costs.

Ruihong Zhang, an agricultural engineering professor at UC Davis, is solving that problem by feeding her bacteria filtered whey, a cheese-making byproduct that’s normally discarded. Not only is it free from dairy companies—they’d normally have to pay to discard this material, so it benefits them as well.There’s also year-round supply of it, unlike other more seasonal agricultural items, Zhang says.

The first step to making PHA is taking the lactose out of the whey with an enzyme called lactase. The product, now without lactose, feeds the bacteria Haloferax mediterranei, which expands and produces PHA in their cells. The cells are immersed in fresh water and a low concentration of acid in a heated vessel for several hours. The PHA naturally separates out and is dried into a powder during this process. The PHA powder is then melted and shaped into single-use bottles, packaging films, and PHA-coated paperboards.

Zhang hopes her technology can bring down prices for PHA (currently about $2.25 to 2.75 per pound) by at least 50 percent and closer to the cost of traditional plastics, which cost about $0.60 to 0.87 per pound to make. She hopes her technology will be commercially available in 3 to 5 years.

At Virginia Tech University, Professor Zhiwu "Drew" Wang, an associate professor of biological systems engineering, is running a four-year pilot project, to create PHAs using food waste.

Because the waste is always going to be nutritionally varied, he uses dark fermentation, a well-established method for treating wastewater, to make the waste more homogenous.

First, the food waste is put into a digester, a sealed container where microorganisms break down organic materials. That waste is broken down into a “cocktail of fatty acids” similar to the liquid at the bottom of the compost, affectionately called “compost tea.” That uniform material is then fed to microorganisms, which multiply and produce PHA until a water filtration process similar to Zhang’s extracts the PHA.

The upfront costs of his technology are a challenge. His 100-liter digester machine, on loan from the University of Michigan, costs a whopping $300,000. In contrast, UC Davis’ Zhang’s digester is $50,000 because her process doesn’t require complete sterilization.

Bioplastics in the future

The most extensive application of bioplastics today is packaging. In 2022, only about 9 percent of packaging was biodegradable, according to one research firm.

Most coffee cups are lined in conventional plastic to prevent you from burning your hands. Starbucks announced in January 2024 that it aims to make 100 percent of its cups either compostable, recyclable, or reusable by 2030. Researchers like Wang say that PHAs will likely be able to act similarly as liners made from traditional plastics.

Companies like Coca-Cola, the largest known contributor to global branded plastic waste, Target, and General Mills, formed the U.S. Plastics Pact in 2021 to adopt 100 percent biodegradable, recyclable and compostable materials packaging by 2030. Members of the pact grew the amount of reused, recycled, or compostable packaging materials from 37 percent in 2020 to 47.7 percent in 2022.

As production methods improve and costs become more competitive, bioplastics have the potential to be used across various industries, including medical, automotive, packaging, and agriculture, providing a sustainable alternative to traditional plastics, according Rafael Auras, a professor in Michigan State University’s School of Packaging. Carmakers like Ford and General Motors are already using soy-based polyurethanes to manufacture seats, headrests and tire gaskets.

Those in the bioplastics market are holding their breaths as they await a decision from a United Nations committee next fall that could force companies that use a hybrid of bioplastics and fossil fuels in their products to create products that are purely biodegradable.

Labeling guidelines identifying types of bioplastics "would go a long way,"says Frank Franciosi, executive director of the US Composting Council.

Without standardized labeling of compostable products, consumers don’t exactly know what they’re buying and how to dispose of it, adds Franciosi. All the effort put into producing plastic that will ultimately break down goes to waste if labeling misleads the consumer, landing the plastic somewhere it can’t degrade in, increasing the amount of plastic waste on our planet.

“I think this is more about getting plastics on the same page globally. Which is a step in the right direction,” Franciosi says.