The strange reasons why people are more likely to die in the winter

World over, more people die in the winter than any other season. Scientists have investigated why for decades. They have some answers—but can’t explain the excess deaths completely.

It’s a curious fact that winter, sleigh bells and Valentine’s Day notwithstanding, is the deadliest season of all. Many more people die in the winter months compared to the rest of the year, a mysterious global phenomenon known as excess winter mortality.

For example, in the winter of 2021-2022, more than 13,000 more people died in the United Kingdom than in other seasons on average. In the United States from 2011 to 2016, 8 to 12 percent more people died in winter months than in non-winter months, according to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. “This annual cycle in mortality is seen everywhere,” says Patrick Kinney, a professor of public health at Boston University. The trend has been recorded in both hemispheres, and even in locations where winter is mild. As those of us in the Northern Hemisphere endure short days and long nights, you might wonder, what is it about winter that makes it such a lethal time to be alive?

These are questions scientists have been asking for decades, and the full answer eludes them. The answer matters because perhaps these deaths are preventable with the right government policy interventions. But to intervene, first, it would help to know exactly why people are dying.

(Do you really need 10,000 steps a day? Here’s what the science says.)

There’s one obvious factor contributing to the excess winter mortality: seasonal viruses. For reasons that continue to be debated, viruses like the flu have a strong seasonal pattern, reaching their peak in the winter months. It depends on the year, but a large fraction of excess winter deaths, sometimes about half of the total number, are from viruses. On their own, though, viruses cannot explain the entire phenomenon. Some of the answer seems to be hidden in the heart.

Cold weather can exacerbate heart problems. But why?

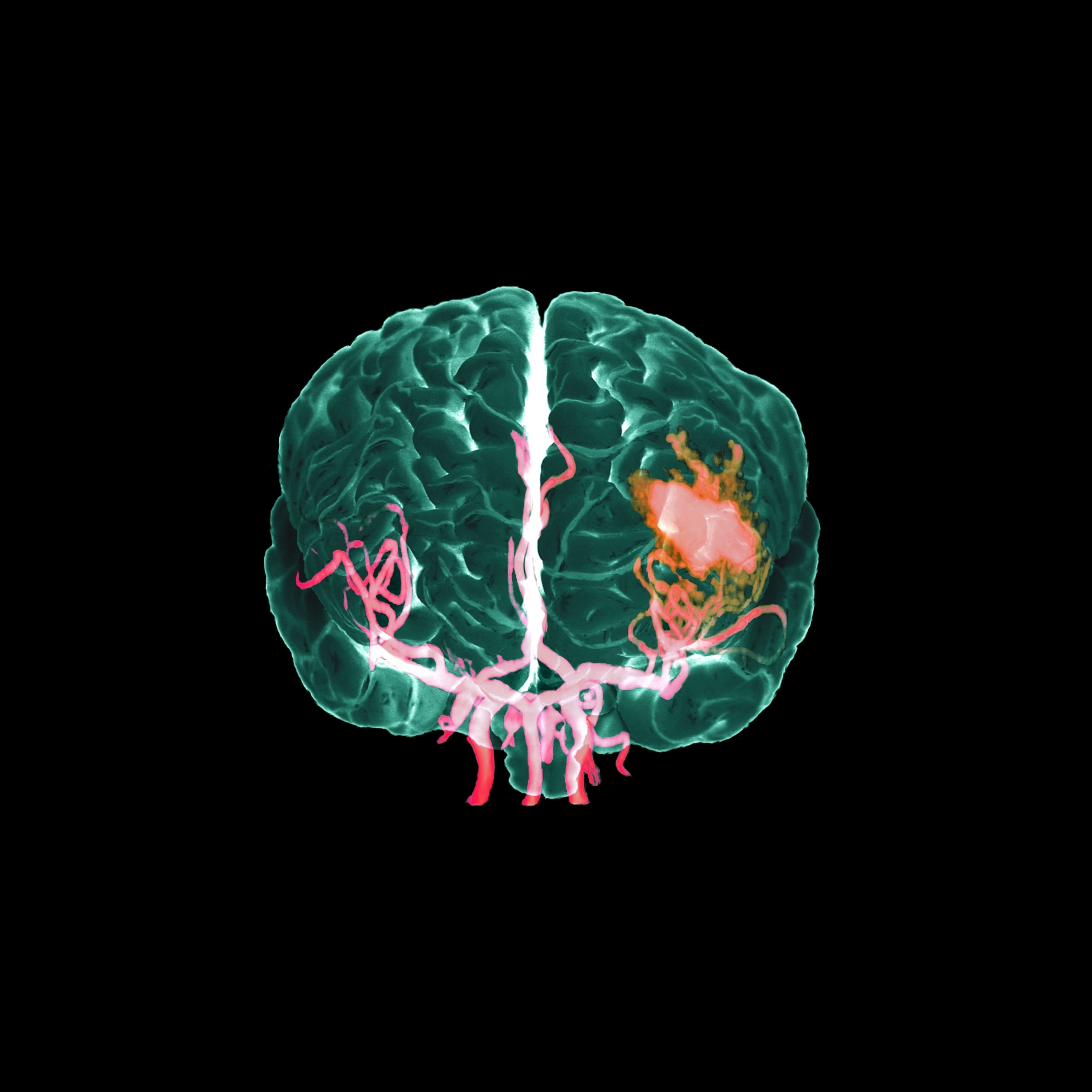

Outside of viral infections, scientists see a clue to the mystery in another common cause of death. “Half of all [excess] winter deaths are from cardiovascular causes,” say Kristie Ebi, a professor of global health at University of Washington, including strokes and heart attacks. “That’s the pattern,” she says. “The question is, why?”

For some researchers who’ve asked that question, the effect of temperature on the circulatory system seems like a promising place to start. If the source of the harm is cold, a campaign to insulate homes or subsidize winter heating costs might help save lives. In the 1970s and 1980s, physiologist William Keatinge at the London Hospital Medical College began to explore whether cold temperatures could be altering the way the human body functions for the worse.

Keatinge performed lab experiments in which subjects were either kept warm or cooled slightly with a fan. He noticed that over the course of six hours, the cold people’s blood subtly shifted. The blood vessels at the surface of the skin, contracting to keep from losing heat, concentrated more blood in the rest of the system. Blood cells in colder people were packed more closely together, and their blood pressure was higher than that of people who were wrapped up in blankets. This suggested temperature stress could be laying the groundwork for clots to form or vessels to burst, which could explain the increased cardiovascular deaths. (In fact, the American Heart Association has invoked a similar concept when warning people to beware of shoveling snow.)

Keatinge also wondered how these physiological findings might relate to trends in the real world. Would colder winters be deadlier than milder ones? He and colleagues compared data on people in European locations as warm as Palermo, Italy (where daily winter temps averaged about 60 degrees Fahrenheit), and as cold as northern Finland (where the average was below freezing at 27 degrees Fahrenheit). They found that there was no particular difference between very cold countries and very warm countries when it came to excess winter deaths.

That didn’t necessary contradict the findings that exposure to cold could endanger the heart, the researchers wrote. Instead, they wrote, the lack of a difference could be because those in chilly climes are prepared for cold, with reliable heating, good insulation, and warm clothing when they venture out. People from warmer places, on the other hand, were caught out by cold days, with colder homes and fewer resources to stay warm.

It was an interesting idea, that people in chilly climates could be protecting their hearts by bundling up or keeping their houses warm. That kind of thinking likely influenced subsequent UK policies, such as the Warm Front program, which helped fund insulation and other home improvements in the early 2000s. A study published in 2008 by Sheffield Hallam University suggested that the intervention and decreased deaths among the elderly were linked.

Since Keatinge’s work began, housing stock has improved in the UK, and heating costs have gone down. The correlation between cold temperatures and excess winter deaths in the UK has faded too, says Philip Staddon, an environmental consultant and visiting scholar at the University of Gloucestershire who has studied human health and environmental change and who wrote about the link in a 2014 paper. He thinks there may indeed have been a link at one time between temperature and deaths, at least in the UK. But it’s probably not the whole story.

Temperature still can’t explain all of the excess mortality

In the last decade, some researchers have made observations that complicate the narrative. Cold temperatures may not be the main factor influencing excess winter deaths, or at least not in all places around the globe.

“Honolulu is really warm, and temperatures don’t vary across the year,” Kinney, who wrote a paper on winter mortality in 2015, says. “And yet people die 10 or 15 percent more in the wintertime than in the summertime?” Something, he felt, didn’t add up. It couldn’t all be down to not having heating.

In their 2015 paper, Kinney and colleagues suggested that there is some other seasonal cause at work aside from viruses and the cold.

Indeed, while colder temperatures may be the most obvious change in winter months, there are numerous smaller changes that might tip the scales toward higher mortality in ways that are not currently understood.

Winter means less sunlight in many places. Lower natural Vitamin D production comes along at the same time. Some people might be eating more or different food—another helping of leftover turkey, anyone?—they might stop exercising, they might drink more alcohol. Even the air is likely to be different—in some parts of the world air pollution is far worse in winter, and in places where pollution is less of an issue, indoor humidity levels can still be radically different. "People change all kinds of things in winter,” says Ebi. In a way, especially in cultures that spend a lot of time indoors, temperature is the least of it.

For Ebi, these other seasonal factors bear further exploration. Perhaps there are physiological changes, aside from those involving temperature, that could be linked to excess winter deaths.

“I live in Seattle. We hibernate in the winter,” she says with a laugh. “All kinds of changes take place. But I haven’t seen any literature trying to test it…I’m still waiting.”