Coral Reefs Could Be Gone in 30 Years

World Heritage reefs will die of heat stress unless global warming is curbed, a new UN study finds.

The world’s coral reefs, from the Great Barrier Reef off Australia to the Seychelles off East Africa, are in grave danger of dying out completely by mid-century unless carbon emissions are reduced enough to slow ocean warming, a new UNESCO study says.

And consequences could be severe for millions of people.

The decline of coral reefs has been well documented, reef by reef. But the new study is the first global examination of the vulnerability of the entire planet’s reef systems, and it paints an especially grim picture. Of the 29 World Heritage reef areas, at least 25 of them will experience twice-per-decade severe bleaching events by 2040—a frequency that will “rapidly kill most corals present and prevent successful reproduction necessary for recovery of corals,” the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization concluded. In some areas, that’s happening already.

“These are spectacular places, many of which I’ve visited. Seeing the damage being wrought has just been heartbreaking,” says Mark Eakin, a reef expert with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, and a lead author of the new report. “We’re to the point now where caction is essential. It’s urgent.”

Mass Bleachings

By 2100, most reef systems will die, unless carbon emissions are reduced. Many others will be gone even sooner. “Warming is projected to exceed the ability of reefs to survive within one to three decades for the majority of the World Heritage sites containing corals reefs,” the report says. (UN announces new biosphere reserves, while U.S. removes some.)

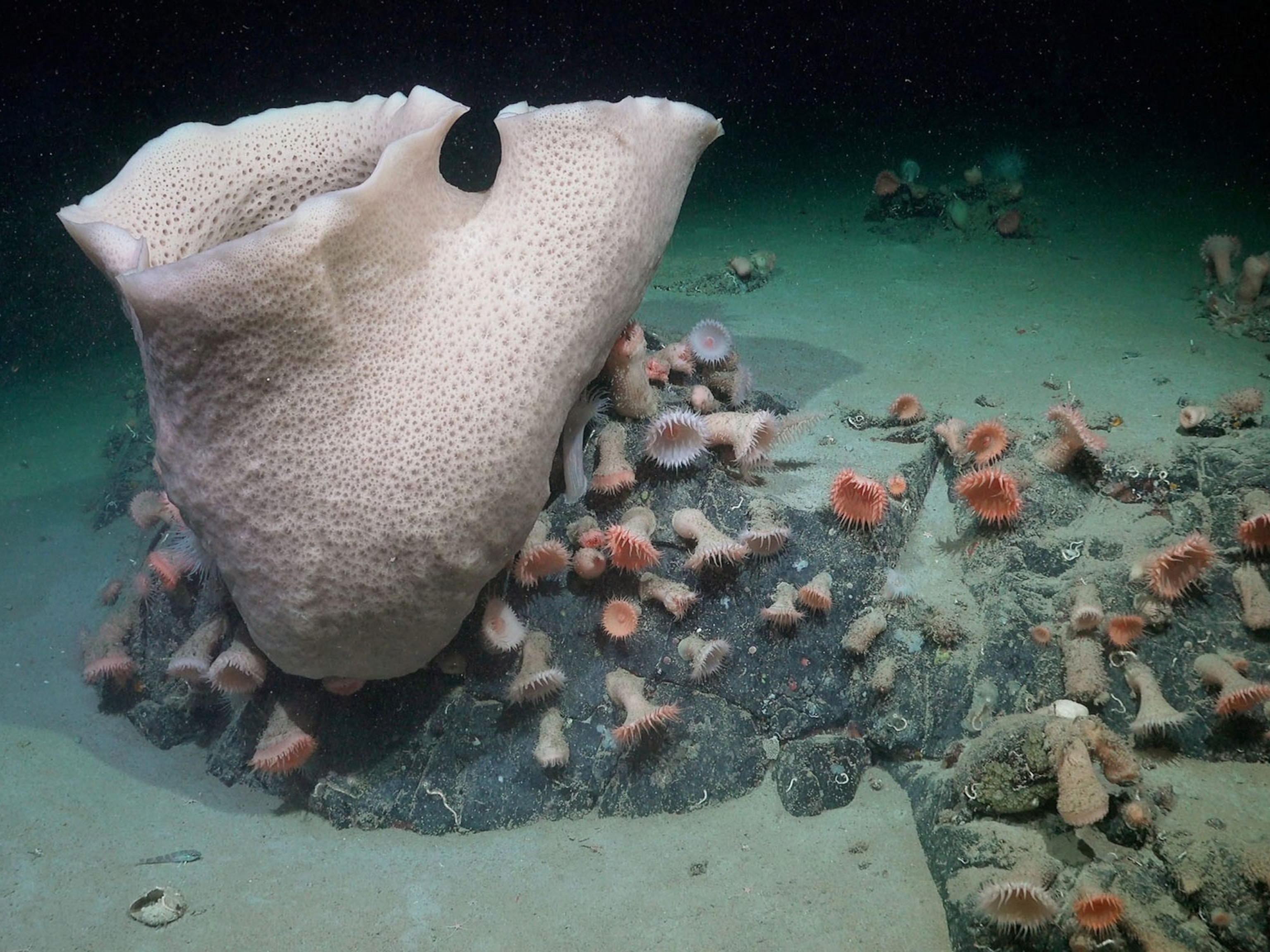

Reefs, often referred to as the rainforests of the oceans, occupy less than one percent of the ocean floor, but provide habitat for a million species, including a fourth of the world’s fish. They also protect coastlines against erosion from tropical storms and act as a barrier to sea-level rise.

“It is terrifying to think of the repercussions of the global and large scale loss of reefs,” says Ruth Gates, director of the Hawaii Institute of Marine Biology in Kaneohe, Hawaii. “The reduction in food supplies, the lack of coastal protection as the reef collapses and subsequent land erosion will make some places unlivable and people will have to move. And that’s not even mentioning the collapse of reef-related tourism.”

In the past three years, 25 reefs—which comprise three-fourths of the world’s reef systems— experienced severe bleaching events in what scientists concluded was the worst-ever sequence of bleachings to date. The Great Barrier Reef was especially hard hit. Other reefs that experienced severe bleaching include the Seychelles, New Caledonia, 750 miles (1,210 kilometers) east of Australia, and the United States, off Hawaii and Florida.

"The last three years have been extremely depressing for me," Eakin, with NOAA, says. "We're seeing truly catastrophic damage to many reef systems around the world. The Great Barrier Reef damage we've seen is greater than anything we've seen in the past 20 years.”

The consequences are already being felt by some people, and will quickly grow more severe, says Eakin's NOAA colleague and co-author Scott F. Heron. Low-lying islands such as Kiribati, a string of 33 coral atolls in the central Pacific Ocean, already see saltwater inundating freshwater drinking sources. Higher tides and crumbling reefs are causing more storm surges. Soon, loss of coral, especially when combined with global overfishing, will translate to fewer fish—and local protein shortages.

"These are real things that real people are experiencing," Heron says. "I've met these people. They've been to my house. This is happening.”

Heron also notes that despite skepticism in some corners about climate change, even the crudest of models from two decades ago predicted just the type of reef damage seen today.

"If what the models projected back then has started to come true, even with all of their issues, then we should have good faith in the science of the current projections," Heron says. "And those projections say if we don't act there will be many, many serious impacts."

Time to Act

Most World Heritage sites are managed locally to control pollutants from farm runoff or overfishing. Now, the “ubiquitous global threat” to reef systems has become so great, Eakin and Heron say, that local protections are not enough. They hope their new, bleak assessment will help the world’s nations to realize that unless they move faster to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, these special places—and the people who rely on them—will suffer greatly, far sooner than expected.

"When someone needs help, the overwhelming majority of us will stretch ourselves to help out—it's a human trait. It's what makes us people," Heron adds. "That the people most impacted by these changes are not necessarily people we encounter in our day-to-day lives does not remove our responsibility to help them."