A global search from the deserts of Mongolia to the highlands of Argentina has revealed the first soft-shelled dinosaur eggs ever discovered, providing a new glimpse into how dinosaurs laid their eggs and parented their young. The emerging picture is that, reproductively speaking, the earliest dinosaurs were like modern reptiles, which generally bury their eggs in nests or burrows and don’t stick around to tend them.

The revelation comes from two teams of international researchers, who have presented stunning new fossils of ancient soft-shelled eggs as old as 200 million years. One group describes the first soft eggshells ever identified among dinosaurs, while the other presents the first fossil egg ever discovered in Antarctica—possibly from a marine reptile—which also seems to have had a soft shell.

The fossils’ mere existence, let alone the quality of their preservation, has left scientists astounded. “How does the saying go: There’s more things on heaven and Earth than we’ve ever imagined?” says Julia Clarke, a paleontologist at the University of Texas at Austin and a coauthor of one of the two studies, both unveiled in today in the journal Nature.

Past dinosaur egg discoveries going back decades featured hard eggshells like those laid by modern birds, dinosaurs’ only living descendants. Bird eggshells contain a layer of the mineral calcite, which makes them stronger and harder, allowing birds to sit on their eggs, or brood, to incubate them. As such, paleontologists most often imagined dinosaurs using similar parenting strategies. But these eggs almost always were dated to the Cretaceous period, late in dinosaur evolution. Now, the mystery of the missing earlier eggs may have an explanation: In all likelihood, they were soft and leathery, which made them more likely to degrade and not fossilize.

Taken together, the new studies add substantially to what scientists know about dinosaur and ancient reptile reproduction.

“There’s more to the fossil record than just skeletal remains,” says Johan Lindgren, a paleontologist at Sweden’s Lund University who reviewed both studies and analyzes fossilized soft tissues, including an ancient marine reptile’s blubber. “Occasionally, you find much more than that.”

Mysterious ‘haloes’ encircling a baby dinosaur

Some of the fossil clues used in the two studies were stashed in the office cabinets of American Museum of Natural History paleontologist Mark Norell—where he keeps high-priority specimens. “They’re the most unthinkably amazing fossils on the planet,” says Yale Ph.D. student Jasmina Wiemann, who likens them to “a sneak peek into the next 10 years in paleontology.”

Wiemann and Matteo Fabbri, another doctoral candidate at Yale, regularly visit Norell in New York to see the fossils he studies. Among this ancient collection, Norell showed Wiemann and Fabbri a clutch of a dozen dinosaur embryos more than 72 million years old that he and his Mongolian colleagues found during a 1995 expedition to the Gobi desert. Mysteriously, the embryos, which belonged to the early horned dinosaur Protoceratops, were encircled by black-and-white films rather than any kind of identifiable hard eggshell.

“Mark showed us this clutch and went, You know, I really think they lay soft eggshells—he just threw it out like this,” Wiemann says. “At first we thought, Probably not. But looking more closely at the fossils, we realized there were these super-weird haloes.”

If Protoceratops laid soft eggs, it’d be the first dinosaur ever found with them, upending years of previous assumptions. Soft eggshells had been discovered for other ancient animals, such as dinosaurs’ distant ancestors and extinct flying reptiles called pterosaurs, but not within the clade of Dinosauria itself.

The team took small samples of the fossils and sliced them thin enough to examine under a microscope. The cross-section revealed that the “haloes” were about a third of a millimeter thick and lacked the standard calcified structure of later dinosaur eggs. “One of the striking, striking things was that there were no eggshells,” Fabbri says.

A new picture of dinosaur parenting

Meanwhile, in what is now the Patagonian region of Argentina, a team of researchers set out in 2012 and 2013 on expeditions funded by the National Geographic Society to search for fossils of a plant-eating dinosaur named Mussaurus that lived more than 200 million years ago.

The expedition found Mussaurus specimens so early in their development, they must have been embryos—but the team was surprised when they couldn’t find hard, calcified eggshells along with the remains. “We could never get it right,” says National Geographic Explorer Diego Pol, a paleontologist at Argentina’s Egidio Feruglio Paleontology Museum. “We were asking the wrong question. We were looking for the wrong thing.”

One day, Pol spoke with Norell, his former Ph.D. adviser, and the two realized that the dinosaur embryos from Mongolia and Argentina shared an unusual lack of calcified eggshells. Pol quickly sent samples to Wiemann and Fabbri at Yale, who took a closer look at the Mussaurus remains.

By shining a laser at the samples and analyzing the light that scattered back, Wiemann deduced the chemical signatures of the ancient

Protoceratops and Mussaurus eggs, as well as the composition of eggs from modern birds, alligators, turtles, and other reptiles. Chemical data from the dinosaur eggs most closely resembled that from other soft eggshells.

Soft eggs don’t retain water as well as hard eggs, which means that Protoceratops and Mussaurus probably buried their eggs like modern turtles or alligators, possibly standing guard for a time or perhaps moving on. The dinosaur lineages with hard eggshells pursued several different nesting strategies, including burying their eggs. But one group of dinosaurs with hard-shelled eggs, the theropods that later begat birds, had open-air nests they brooded—a much more involved form of parenting.

To trace the evolution of dinosaur eggs, Fabbri plotted a family tree back to roughly 250 million years ago and found that the common ancestor of all dinosaurs most likely laid soft eggs. The work suggests that calcified eggshells didn’t evolve once among dinosaurs, as previously thought, but at least three different times. Suddenly, the researchers say, the wide diversity of dinosaurs’ hard eggshells has an explanation.

“Everything is starting to tie together really nicely,” Wiemann says.

A huge egg in Antarctica

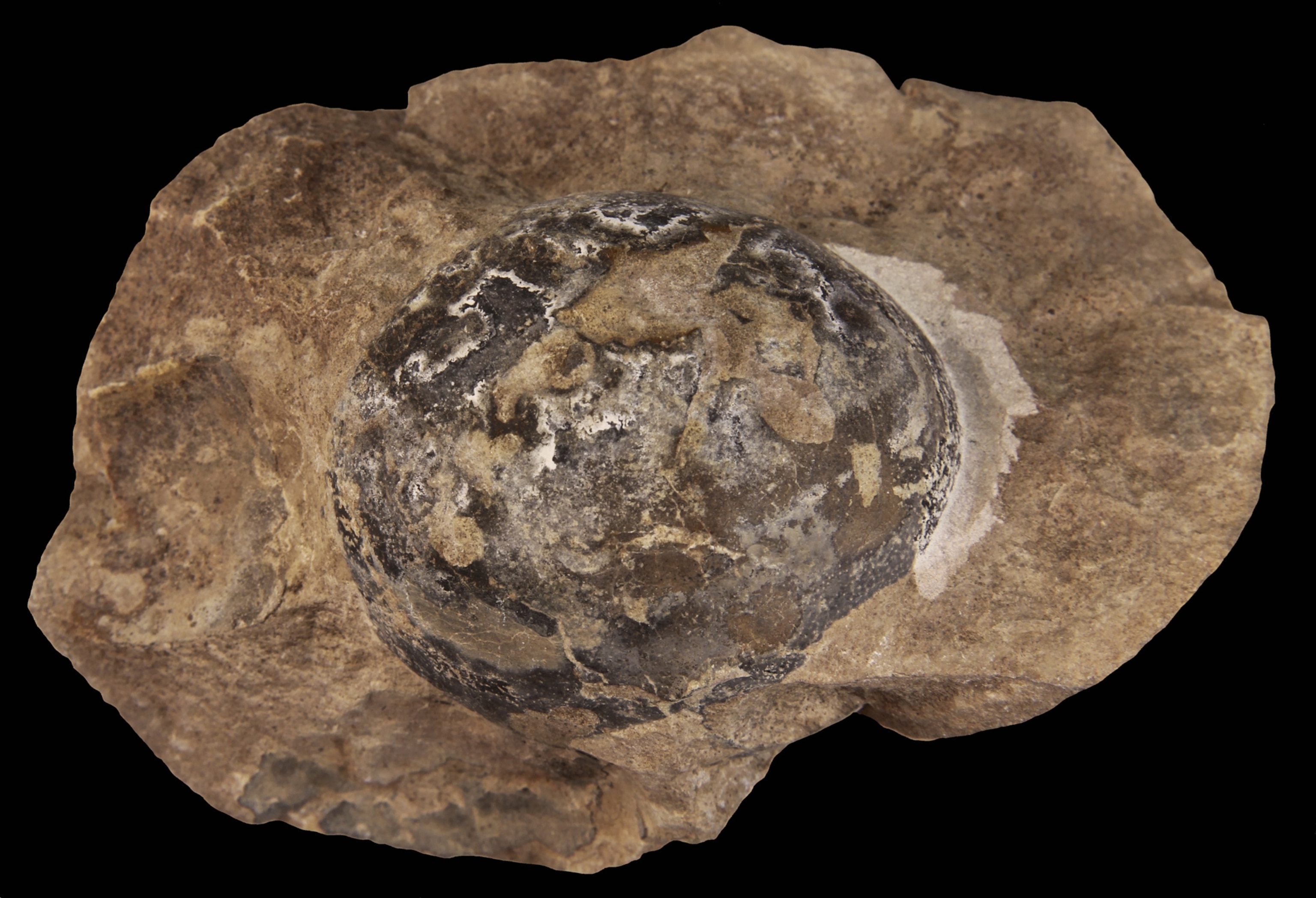

Farther south, in the rocks of Antarctica, another egg has captivated scientists—the second largest fossilized egg ever found, measuring nearly a foot long.

The 68-million-year-old egg, called Antarcticoolithus bradyi, is the first fossil egg ever found in Antarctica, only outsized by the eggs of Madagascar’s extinct elephant bird. Antarcticoolithus is also one of the few fossil eggs ever found in marine sediment. “For the first egg remnant from Antarctica to be a nearly complete egg that has finely preserved microstructure is kind of insane,” says Julia Clarke of UT Austin.

Antarcticoolithus was discovered in 2011 by a team of Chilean researchers on an expedition to Antarctica’s Seymour Island. The bizarre, deflated lump mystified the team. When study coauthor David Rubilar-Rogers, a paleontologist at Chile’s National Museum of Natural History, introduced the fossil to Clarke in 2018, he called it “The Thing.”

Under a microscope, Antarcticoolithus not only lacked the internal structure of hard eggshells, but also the pores of hard-shelled eggs, suggesting the large egg was soft.

At the time the egg was laid, large marine reptiles called mosasaurs lived in the Antarctic waters where the fossil egg was entombed. The bones of a mosasaur were found less than 700 feet from the site, suggesting the egg may have belonged to these 20-foot-long swimming reptiles.

However, the egg doesn’t have any bones inside, so nobody knows the parent’s identity for sure. Other ancient marine reptiles are known to have given live birth like modern whales. If mosasaurs did lay eggs, their babies would have had to hatch immediately to surface and take their first breaths.

Could Antarcticoolithus have come from a dinosaur? If it did, the large egg was almost certainly laid on land and then washed out to sea. “Hopefully, if they excavate that area more, they will find embryos associated with similar eggs, and then we would know,” Lindgren says. (Read about Spinosaurus, the first known swimming dinosaur.)

These prehistoric eggs collected from around the world underscore how much scientists have yet to learn about reptile evolution, particularly among dinosaurs, whose earliest members buried their eggs like many modern reptiles, as well as their distant reptilian ancestors from more than 250 million years ago.

“We thought about dinosaurs as special reptiles for all this time ... At least in their beginning, they were not so special,” Fabbri says. “We are overturning what we were assuming for decades.”