Cases of ‘flesh-eating’ bacteria rose in Florida this year. Here’s what to know.

Vibrio bacteria sickened dozens of people following Hurricanes Helene and Milton, and the microbes’ range appears to be increasing up the East Coast as climate change warms coastal waters.

The massive flooding during last fall’s hurricanes that tragically washed away homes and communities across western Florida also brought a dangerous foe ashore—a microscopic bacteria that sickened and killed dozens of people.

The bacteria, Vibrio vulnificus, thrive in warm brackish waters that were pushed inland from coastal waters in the Gulf of Mexico and the Atlantic Ocean. The microbes can destroy the skin, cause severe gastrointestinal illness, and result in deadly sepsis. Largely due to the storms, severe cases in Florida doubled in 2024 from a year earlier, sickening 82 people in the state as of early December; 16 of them died.

Floridians aren’t the only people with increasing exposure to the dangerous microbe, which generally causes 500 hospitalizations and 100 deaths across the United States. Vibrio bacteria thrive in water that’s 59 degrees Fahrenheit or warmer. Now that climate change is more frequently raising water temperatures above that threshold, the bacteria—once rarely seen north of southern Georgia—are appearing up the U.S. East Coast. Experts predict that by 2041 illnesses caused by V. vulnificus will be common around New York, and by the turn of the next century every eastern state will have significantly increased infections.

Vibrio has also burgeoned at higher latitudes internationally, especially around Chile and the countries bordering the Baltic Sea where water temperatures have risen faster than in other places. Scientists estimate that across the globe, conditions favorable to Vibrio appear on 10 percent more days than in the 1980s.

“Before we started seeing global temperatures increase, Vibrio cases were quite rare. As the suitable conditions for their proliferation become more widespread, it’s natural that cases of these pathogens become more abundant,” says Salvador Almagro-Moreno, whose lab studies the microorganism at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital in Memphis, Tennessee.

Yet despite the growing health menace, little is known about why some strains are dangerous and others benign, why the problematic strains inhabit only certain waters, and exactly how they behave in the human body. As more Americans continue to be exposed, answering these questions will be crucial.

What is Vibrio?

Of the more than 100 species of Vibrio, four cause the majority of health concerns. Most of us are at least indirectly familiar with the ailments they cause.

V. vulnificus, the type that sickened people in Florida, is the microbe behind most of the headline grabbing “Flesh-eating bacteria kills fisherman” stories in the press. This species, as well as Vibrio parahaemolyticus and Vibrio alginolyticus, contaminates shellfish like clams and oysters, which can decimate fish stocks and cause severe G.I. symptoms and dehydration in people who eat them raw or undercooked. And the bacteria Vibrio cholerae is behind the diarrheal disease cholera, which across the globe sickens up to 3 million people annually and causes 95,000 deaths.

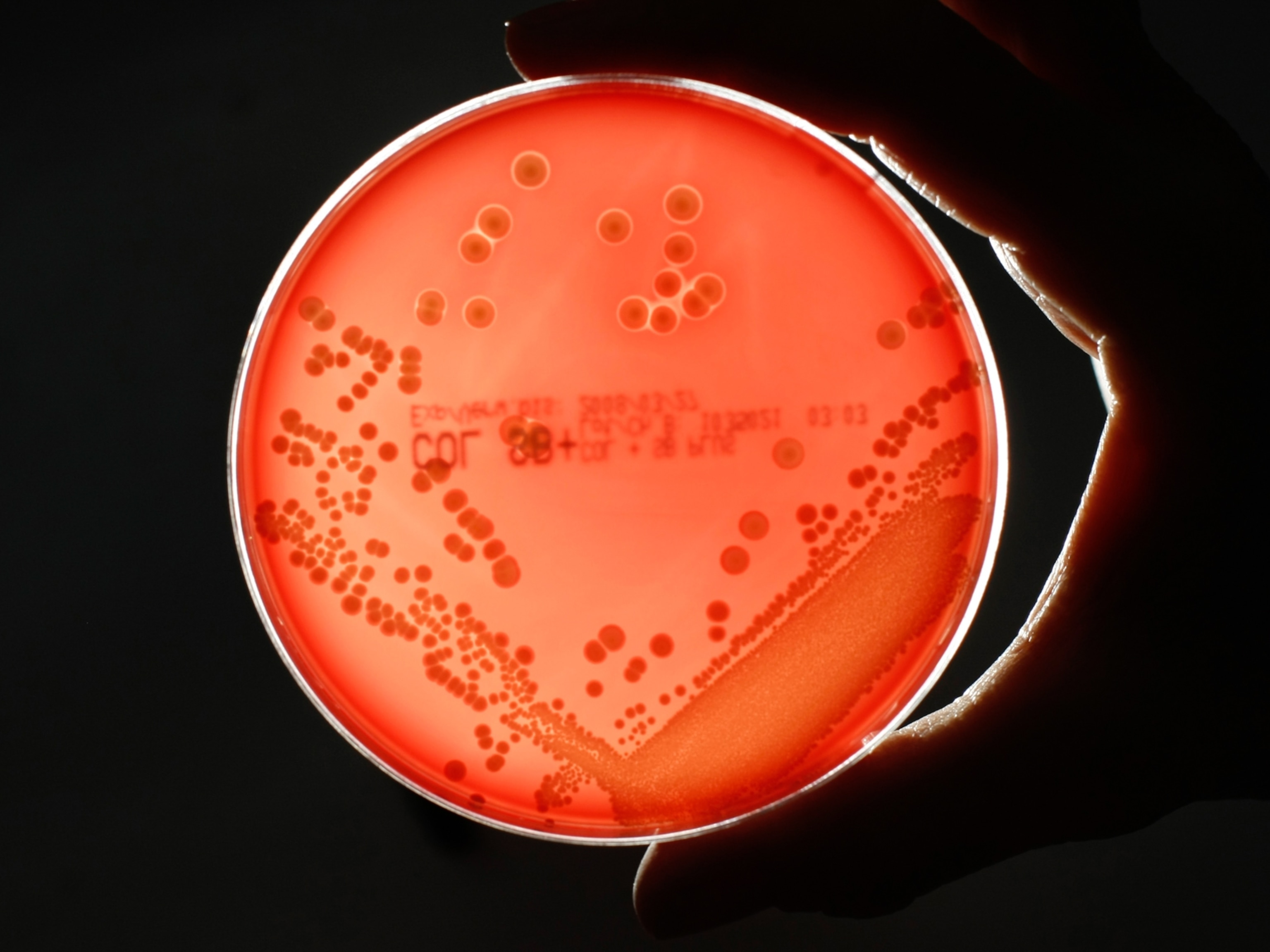

Even within these species, some strains are harmless. Researchers are currently working to determine the specific factors, including water salinity, nutrient availability, and surrounding biodiversity, that allow the most dangerous strains to thrive.

While hazardous varieties rarely appear in the Pacific Ocean, strains of V. vulnificus are endemic in the Atlantic Ocean and Gulf coastal waters. Even in their natural environment, scientists don’t completely understand their roles there, although one function is likely degrading the “marine snow” left by decomposing crustations, Almagro-Moreno says.

With vast patches of the ocean low on the nutrients they need to survive, the bacteria spend much of their time in a dormant state. But when exposed to an influx of nutrients, they grow and multiply in “blooms.”

How do people get infected—and who is most at risk?

The increased cases near the Florida Gulf coast largely resulted from contact with people inundated with infected water. “You have people out there trying to put their property back in order, and they’re exposed to warm, standing water. These are exactly the kinds of conditions that Vibrio can thrive in,” says Maya Burke, assistant director of the Tampa Bay Estuary Program charged with keeping the west coast waterway safe and clean.

It’s also possible massive nutrients flushed into the water from the storms led the Vibrio to bloom. This includes pesticide runoff from lawns, raw sewage spewed into waterways from broken aging wastewater pipes, and a waste byproduct from fertilizer plants called phosphogypsum—that also happens to be radioactive.

Monitoring in the Tampa Bay after the hurricane revealed Vibrio was present, Burke says, although exact numbers and types are not yet available. The region does not monitor Vibrio levels on an ongoing basis, she says.

(Many Americans are buying homes in flood zones—and don't realize it.)

Because Vibrio blooms when exposed to nutrients, they proliferate quickly in both the human intestine and bloodstream. “They are some of the fastest growing organisms on Earth. They get inside the host and they find this warm, nutrient-rich environment and they proliferate really fast,” Almagro-Moreno says. (Whether some Vibrio linger in a dormant state inside the human body is less clear.)

What does a Vibrio case look like?

Vibrio can enter the body a few different ways. Symptoms of exposure to dangerous strains via an open wound include redness, pain, swelling, discoloration, discharge and eventually, dead, blackened skin. (The latter inspires its “flesh-eating” nickname.) Swallowing affected sea water or eating contaminated seafood brings diarrhea, stomach cramps, and vomiting. If the infection enters the bloodstream, early symptoms include fever, chills, and dangerously low blood pressure.

This leads to death in 20 percent of people who develop an infection, known as vibriosis, sometimes in just one or two days.

What makes the bacteria so deadly is their ability to multiply quickly. “If you saw something weird in your finger or foot you would seek treatment. But the problem is you might get infected during the day and by the time you wake up the next morning, you have septicemia,” Almagro-Moreno says.

“If you get it, you have to act really fast,” says Mohammad Moniruzzaman, a microbiologist at the University of Miami. Most antibiotics, taken early enough, effectively treat it. Severe wound infections may require tissue removal or amputation. That’s why Moniruzzaman advises avoiding coastal waters if you have an open wound, or at least, covering it with a water-resistant patch.

Vibrio infections are especially dangerous for people who are older or who have a weakened immune system or certain chronic diseases. A review article in the Lancet notes that people with liver disease are 200 times more likely to die from V. vulnificus than those with healthier livers.

Efforts to avoid Vibrio’s impact

The increase in Vibrio bacteria caused by climate change is also affecting the seafood industry. Tilapia and shrimp farms have been hit especially hard by Vibrio outbreaks. A paper published in the journal mBio called Vibrio “a rising problem for aquaculture worldwide.” Fish mortality rates at some seafood farms have been as high as 80 percent after an outbreak, Almagro-Moreno has reported. In rare cases, oysters from Alaska have even been affected.

With East Coast waters staying warmer into fall, allowing Vibrio species to bloom and flourish for longer stretches, the old admonition to avoid raw oysters in months not containing the letter R—that is, late spring and summer—may no longer be far-reaching enough to provide protection. As it is, each year more than 50,000 U.S. cases of vibriosis result from eating contaminated seafood—a number almost certain to grow as the bacteria do. Almagro-Moreno suggests taking a page from New Orleans food traditions and frying or broiling clams and oysters rather than eating them raw.

(Here’s how climate change may make shellfish—and us—sick.)

While there are no comprehensive surveillance systems tracking disease-causing Vibrio, countries are increasingly recognizing the risks and taking steps. The European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control created a map to try to predict when conditions like sea surface temperature and coastal salinity are especially ripe for blooms.

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention collects information on cases from state public health officials, which can aid source tracings during outbreaks. The data are incomplete—most vibriosis cases go unreported, counts aren’t published every year—but they show a shift inland. In 2012, most surveilled cases came from the Atlantic and Gulf Coasts. By 2019, infections in non-coastal states leaped 10 percent, likely from contaminated seafood brought into the area.

Better surveillance of waterways likely to contain Vibrio will become increasingly important as climate change continues warming waters and infections rise. That’s because individuals cannot tell by observing the water before they plunge in whether they are present. “They are marine bacteria,” Moniruzzaman says. “They will grow in water that looks clear and beautiful.”