Health food packaging buzzwords are confusing. This guide can help.

We explain the difference between organic, non-GMO, and certified naturally grown—and whether they're worth paying a premium for.

Grocery shopping can be a dizzying experience these days.

If choosing among a dozen different yogurt flavors wasn’t overwhelming enough, there’s also the growing, confusing list of buzzwords on packaging labels. Is there a nutritional difference between organic Greek and regular? Is naturally grown healthier? What does it even mean for yogurt to be bioengineered?

While ostensibly created to educate consumers about how food is grown or processed, excessive labeling can have the opposite effect.

“Food labels can be very useful. And I'm saying ‘can be’ because sometimes they're not,” says Ariana Torres, an agricultural economist and associate professor at Purdue University. The problem, she says, is that too much information can muddy the waters—making it harder for consumers to determine what labels actually mean and distinguish real certifications from empty marketing.

Food marketing experts weigh in on the most common food labels to demystify the claims and help consumers make educated choices about whether to pay the premium.

Organic

The term “organic,” which was first used in reference to farming in 1940, has come to describe a multi-billion dollar industry that represents nearly 6 percent of all retail food sales in the United States. And market research has shown that, while price premiums have fluctuated over the years, they’re generally trending upwards, with consumers willing to pay an average of 58 to 92 percent extra for organic over conventional produce and nearly 200 percent more for products like eggs. But what does organic mean, exactly?

Organic encompasses a broad spectrum of factors, from soil quality to pest control and use of additives, according to the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), which regulates the market through its National Organic Program (NOP). For a product to receive the ubiquitous green “USDA Organic” label, it must meet a long list of requirements for growing, processing, and handling. At least 95 percent of a product’s ingredients must be organic to be certified.

Broadly speaking, organic products are guaranteed to be grown without synthetic fertilizers and pesticides, contain no artificial preservatives, colors, or flavors, and are produced without certain prohibited practices, such as genetic engineering. The term genetically modified organism (GMO) describes any plant, animal, or microbe whose DNA has been changed through the use of technology. All organic products are GMO-free, though not all non-GMOs are organic.

Organic farmers are also required to use methods that “foster resource cycling, promote ecological balance, maintain and improve soil and water quality, minimize the use of synthetic materials, and conserve biodiversity,” according to the USDA.

Kathleen Glass, associate director of the Food Research Institute at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, describes purchasing organic as “a lifestyle choice,” adding that there’s no evidence that organic is more microbiologically safe than conventionally grown foods. Compared with 50 years ago, she says, the amount of pesticides and herbicides allowed on food are well below levels that could cause long-term health impacts.

Robert Paarlberg, an associate in the sustainability science program at the Harvard Kennedy School, says that there’s “no convincing evidence” that organic products are better than conventional from a nutritional or food safety perspective.

“Certified Organic does not mean much from a nutritional standpoint,” says Walter Willett, a professor of epidemiology and nutrition at Harvard. While organic products will have lower levels of pesticides and herbicides, he says that the health benefits of that are still unclear. “If the cost is similar, I would suggest the organic option, but for those on a limited budget, eating plenty of healthy foods would be more important,” he says.

Certified Naturally Grown

Consumers wanting to steer clear of synthetic chemicals and genetic engineering might also look for the “Certified Naturally Grown” label—and should be aware that any product claiming it’s “naturally grown” is not quite the same.

Though the standards are essentially the same as organic, the verification process differs slightly, says Alice Varon, executive director of Certified Naturally Grown, the independent nonprofit and certifier. “Certified Naturally Grown means that the food was grown without synthetic inputs or GMOs and that the practices of the farmer were verified through a peer-review inspection process.”

Founded and run by farmers, Certified Naturally Grown was created as an alternative for growers and producers intimidated by the “onerous,” national organic verification process, Varon says. Unlike organic, the CNG label implies locally grown and primarily covers minimally processed or non-processed foods like fresh produce, honey, sauerkraut, and salsa.

Whereas terms like “all natural” and “free-range” have no formal definition and can be used as an unverified, unregulated marketing ploy, Chris Berry, associate professor of marketing at Colorado State University, says that CNG—and other government or third-party certifications—are “something that consumers can rely on.”

Still, there’s always a margin of error, according to Varon. Unlike GMO certifiers, the CNG doesn’t conduct post-production lab testing, so cross-pollination with nearby conventional GMO corn fields, for instance, could potentially go unnoticed. “It’s entirely possible that there’s some contamination,” she says, adding, “That’s the nature of the food system.”

Non-GMO and bioengineered

While there’s widespread agreement that GMOs are as safe as any other foods, many consumers still want to know which is which. Though only a handful of GMO crops are grown in the U.S., several—including corn, soy, and sugar beets—are major players in the food market, both as ingredients and as feed for livestock.

One way to tell the difference is to look for products with the Non-GMO Project Verified label. The private nonprofit certifies goods free from organisms modified through any form of biotechnology. That means that, in a bag of non-GMO chips, not only must the potatoes be free from GMOs, but also any processed ingredients, like the canola oil used to fry the potatoes into chips.

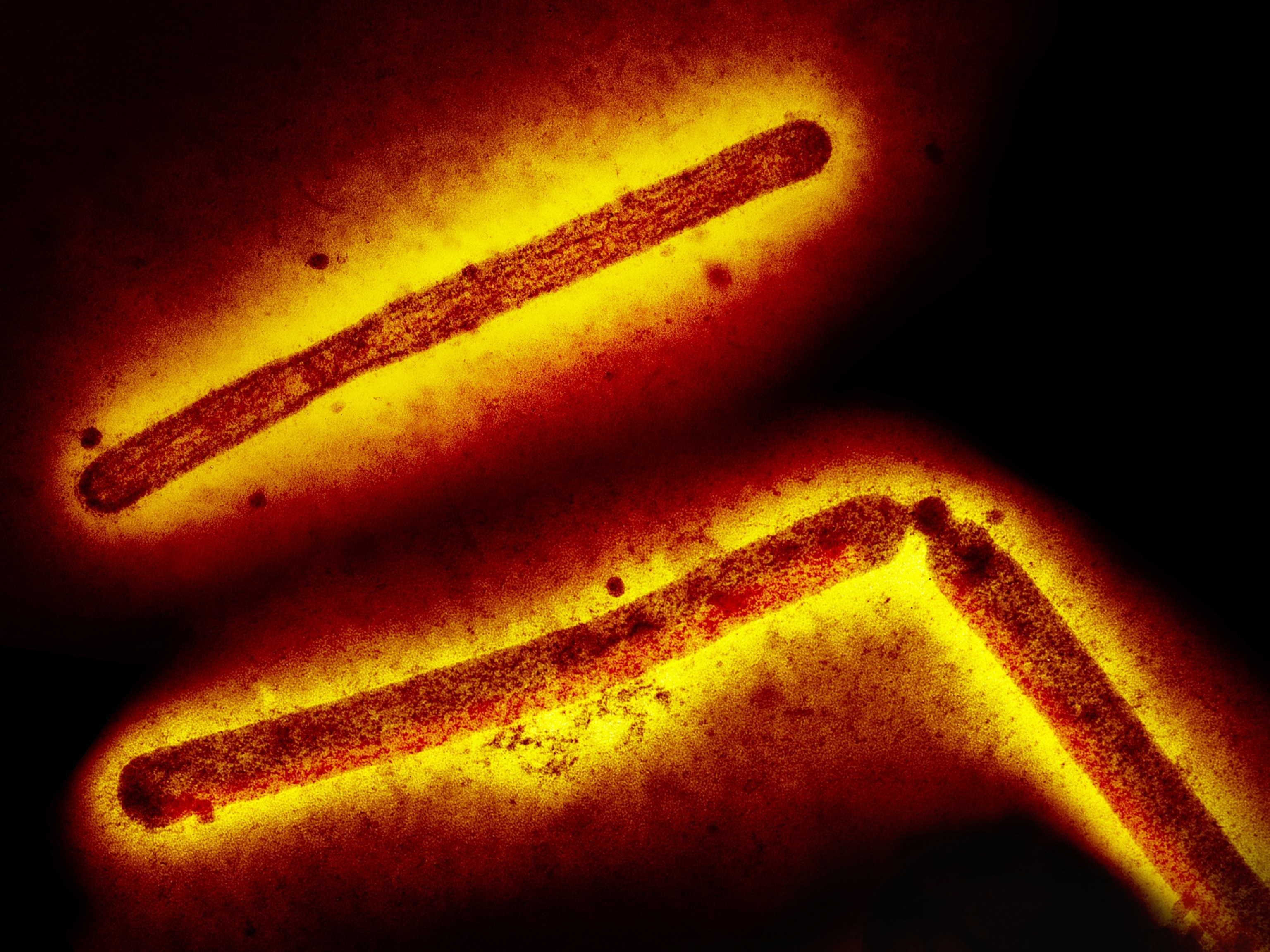

While the Non-GMO Project sets the standards and makes the final certifying determination, independent companies conduct the actual genetic testing. These contractors use a lab technique called polymerase chain reaction (PCR) to test for the presence of genetically modified materia in DNA, says Hans Eisenbeis, the director of mission and messaging at the Non-GMO Project. To put it simply, he adds, they’re looking out for products that “can’t occur in nature and can only occur in a lab.”

Per Non-GMO Project standards, certain “high-risk ingredients,” like apples and canola, are allowed to contain a small percentage of genetically modified material.

“Contamination happens,” Eisenbeis says. Still, if you see the label, he adds, “you can be really confident that you are meaningfully avoiding every GMO that a human being can avoid.”

The USDA regulates a similar, but inverse label—bioengineered—to identify foods with a detectable amount of genetically modified material. The Non-GMO Project defines GMOs broadly and includes genetic modifications used at any point during food production. The federal designation, on the other hand, is much narrower. Bioengineered uses a higher threshold for contamination and excludes processed foods made from bioengineered crops with undetectable amounts of modified genetic material.

From a nutritional standpoint, there is no difference between GMO and non-GMO foods. However, Non-GMO Project certification could help justify manufacturers in raising product prices, which also reinforces—as premiums often do—the idea that the non-GMO option is somehow better. Recent studies have shown that non-GMO foods can cost anywhere from 10 to nearly 75 percent more.

Labels can often be a “marketing tool” more than anything else, Torres says. “We need to educate consumers…because some labels actually don't have a real value or added value to a product is just a label.”

While consumers may prefer to eat non-bioengineered foods, a USDA spokesperson emphasizes that the label is meant only as “a marketing standard and does not convey information about the health and safety of foods.”