Mysterious crocodile relative may have walked on two legs

Odd fossil footprints once attributed to a pterosaur seem to actually belong to a croc-like animal that lived more than 110 million years ago.

Over 110 million years ago, during the Cretaceous period, the southern coastal area of South Korea, near the city Jinju, was covered by extensive lakes. The muddy shores were inhabited by frogs, lizards, turtles, and dinosaurs, all of which left their tracks in the muck. Whenever the water level rose, some of these footprints were filled with sand, allowing a fraction of them to be preserved.

Today, thousands of tracks can be found in this area, known as the Jinju Formation, says Martin Lockley, a paleontologist who specializes in trace fossils like footprints—known as an ichnologist—at the University of Colorado Denver. Lockley and colleagues in South Korea have studied the tracks at Jinju for decades, and for many years, they’ve been mystified by some of the largest footprints.

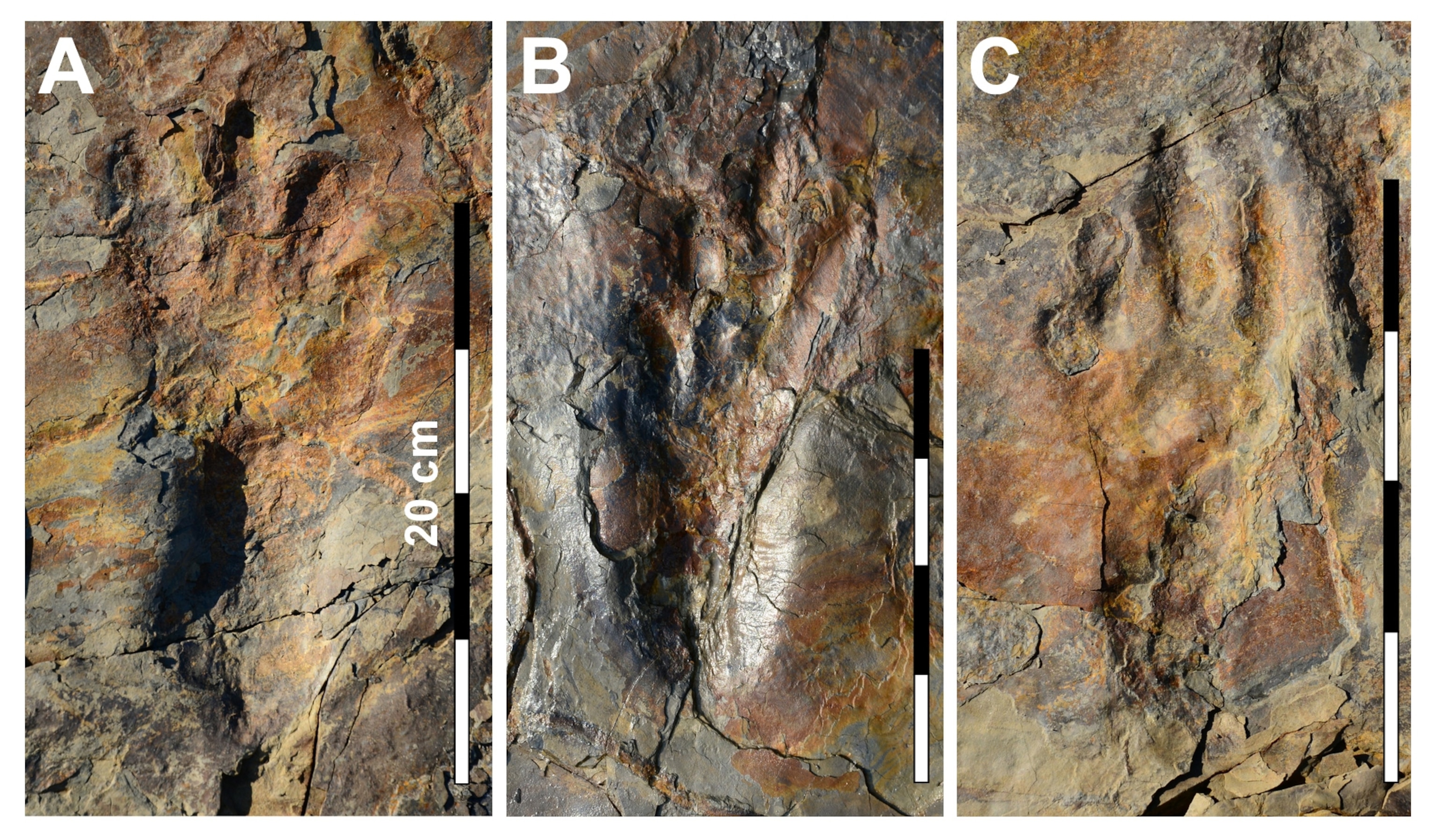

In 2019 they finally discovered detailed imprints from the creature, reported today in Scientific Reports. The tracks provide an impression of the animals’ toes, the pads on the bottoms of their feet, and even the occasional patch of skin. These details have convinced Lockley and his colleagues that the footprints likely were left by crocodylomorphs, crocodile relatives, that were over nine feet long. They appear to have been unusual crocodilians, leaving imprints only from their hind feet, suggesting the animals were bipedal.

“[The imprints] really do look like they were made by big crocodilians,” says ichnologist Anthony Martin, of Atlanta’s Emory University, who was not involved in the new study. “Indeed, by ones that were walking on their rear feet and on land. That’s pretty weird. But then again, the Cretaceous was a weird and wondrous time.”

Mysterious footprints from the Cretaceous

Before the prints were found, paleontologists only had tracks from this animal that were “very poorly preserved,” Lockley says. “They are just oval impressions, 10 to 12 inches long and 4 to 5 inches wide.”

Lockley and his colleagues hypothesized in 2012 that these tracks, found in the nearby Haman Formation, may have been made by a large pterosaur—a flying reptile that lived alongside dinosaurs—perhaps wading in shallow water, trying to keep its wings from getting wet. But whatever it was, the gait of the animal and the lack of clear forelimb imprints suggest it was walking on two legs—and other tracks suggest that pterosaurs generally used four legs when on the ground.

The tracks discovered last year in the Jinju Formation gave paleontologists a much better look at the animal’s feet. “When Martin Lockley visited the site in November 2019, I asked him what he thought of these tracks,” says Kyung Soo Kim of Chinju National University of Education in Jinju, whose team discovered the tracks. “He immediately suggested that they were of the type known as Batrachopus, a crocodylian. I didn't believe it at that time, because I couldn't imagine a bipedal crocodile. But later, I was convinced by the blunt toes, the toe pads, and the details of the skin.”

It was a croc unlike anything alive today. In addition to walking on two legs, it left a very narrow trackway, “putting one foot in front of another,” unlike modern crocodilians, Lockley says.

The idea of a bipedal crocodilian might seem bizarre, but it is not entirely unheard of. A few previous studies have proposed that early crocodylimorphs living in North America during the Triassic may have been bipedal as well. But given the long period of time between these early crocs’ occurrence and the creature that left the large prints in South Korea, paleontologists are not sure whether two-legged crocs survived this entire time with a gap in the fossil record, or if the ability to walk on two legs evolved more than once.

The researchers therefore suggest this latest bipedal croc is a new “ichnospecies”—based solely on tracks—that they’ve named Batrachopus grandis.

An upright croc

If some crocodylomorphs were bipedal a hundred million years ago, why are today’s crocodiles all lumbering about on four feet? Lockley believes that in the Cretaceous, it would have been beneficial for some species to be a bit higher on their legs, similar to many carnivorous dinosaurs. “The landscape was very flat, a good area for running around and hunting on sight.”

A possible alternative explanation for the tracks is that the animals were floating on the surface of a lake while pushing themselves forward with their legs. But Lockley believes that if this were the case, the animals wouldn’t have left such nice, regularly spaced imprints. “Nobody has ever gone and drained the swamp to tell us what the [underwater] footprints of crocodiles look like,” he says. “But they’re often just pushing off with their toes, they don’t put the whole foot down.”

“Swimming is the first thing that came to mind,” says Ryan King, a track expert at Western Colorado University, but he agrees that would probably leave an impression of the toes and not the rest of the foot. “Also the preservation of the pads—even the skin—make it more probable the feet were impressed into a moist, firm substrate on land than underwater.”

Although the crocodylomorph has been identified as a new species based on its footprints, scientists have not matched the prints to a fossil skeleton. Tracks like the ones recently found are thought to have been made by extinct crocodylomorphs of the genus Protosuchus. But scientists don’t know for sure. “Unfortunately, very few animals have died in their tracks, as it were, to leave us with an unmistakable link between a trace and a body fossil,” Lockley says.

Ichnologists sometimes wish other paleontologists studying fossil bones would pay more attention to the footprints these creatures left behind. After all, Lockley says, they are traces of “the living animals and their behavior, when they still had skin on their bones.” Sometimes scientists can fit hand or foot bones to a track, but “for many animals, we lack good fossils of those fragile parts.”

Gradually, bipedal crocodylomorphs appear to have been outcompeted by warm-blooded mammals. “That may be why today you don’t see crocodiles running after antelopes on the savanna,” Lockley says. But when the wildebeest have to cross the Mara River in Kenya and Tanzania, there’s still only one predator they’re worried about.