In a few days, while Earth rings in another orbit around the sun, a robotic ambassador will be flying close to a small ball of rock and ice deep in outer space. Called 2014 MU69, the mysterious object is more than 43 times farther from the sun than Earth—meaning that if all goes to plan, it will soon become the most distant object that humans have ever explored.

MU69, also dubbed Ultima Thule (pronounced Ul-tee-ma TOO-ly) by the mission team, is the first solar system object discovered after its robotic visitor launched: The celestial body was found in images from the Hubble Space Telescope while NASA's New Horizons probe was already en route toward its historic flyby of Pluto in 2015.

The 30-mile-wide object is a resident of the Kuiper belt, a region thought to be populated by relatively pristine leftovers of the dust and gas that birthed the planets. By getting in close with New Horizons, scientists hope to reveal profound insights into the solar system's formation. But Alan Stern, the mission's principal investigator, emphasizes the many unknowns that MU69 presents.

“No spacecraft has visited a small Kuiper belt object, so we don't know what to expect,” Stern says. “Every time we've done a flyby of a new class of objects, we usually found ourselves spurned by the richness of nature—finding ourselves in a completely different regime scientifically than we expected.”

Preparing for Pluto

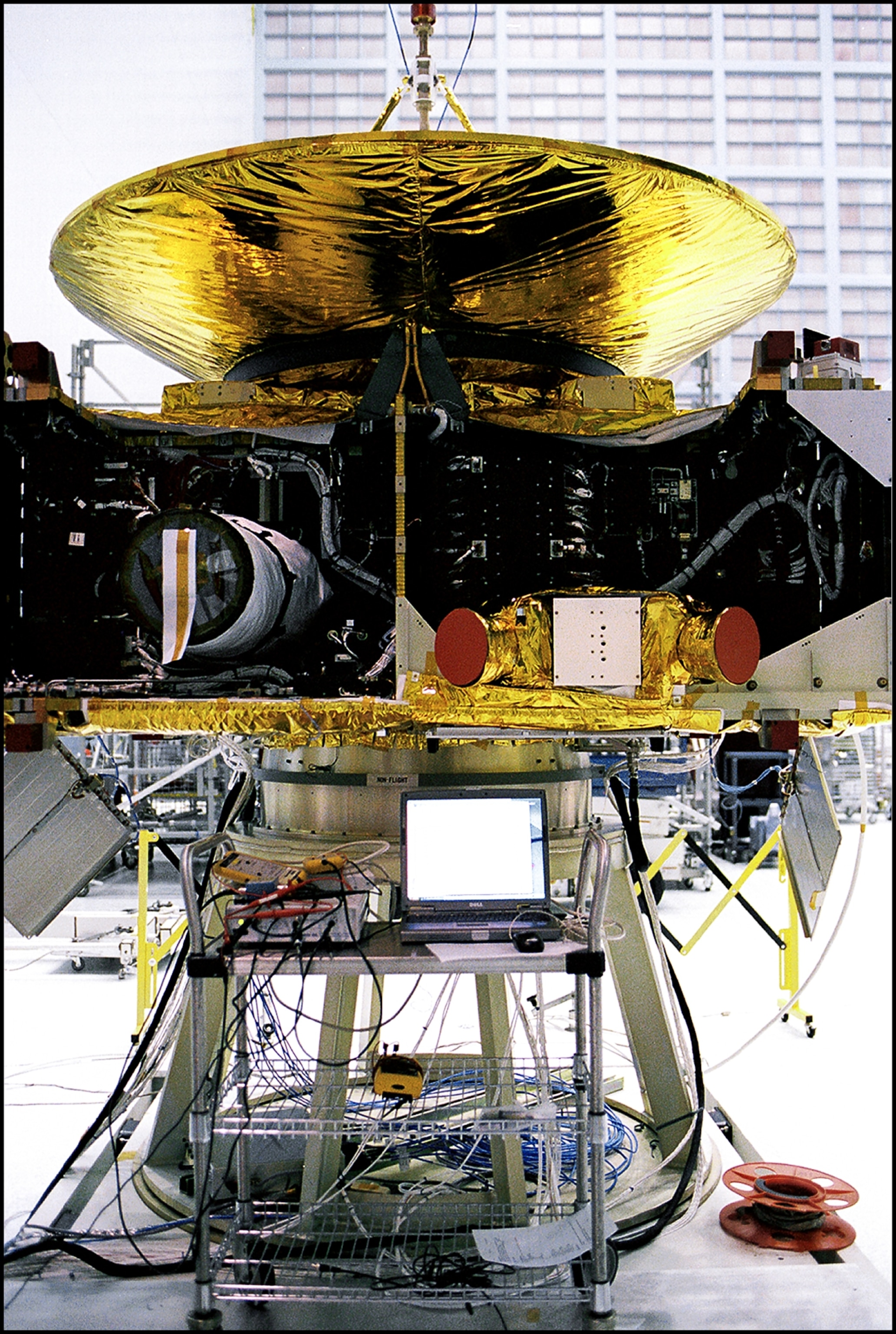

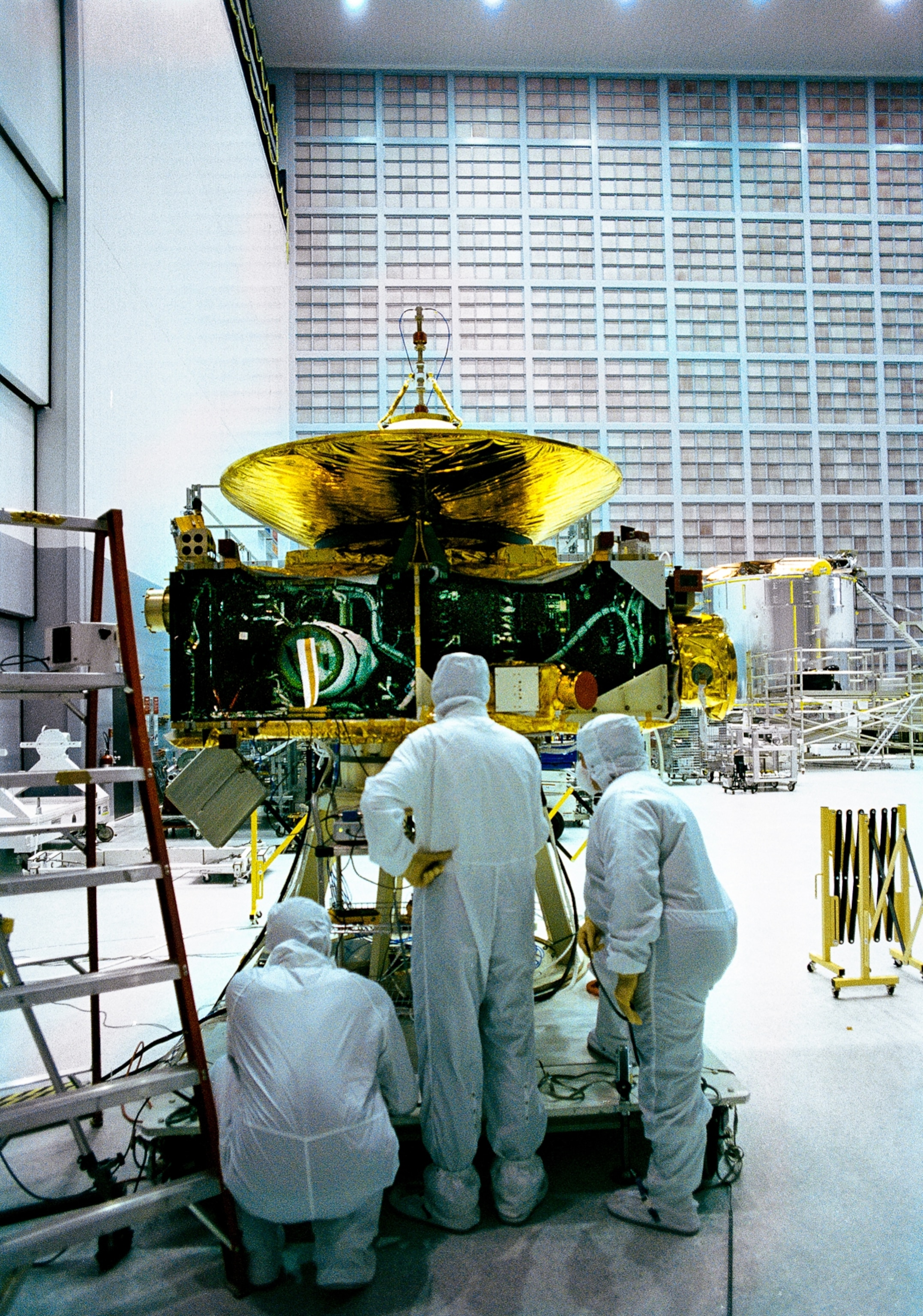

New Horizons's record-breaking run of exploration began on January 19, 2006, when it launched from Earth with its sights set on Pluto. With a velocity of 10 miles a second, New Horizons was at the time the fastest spacecraft ever launched. Only the Parker Solar Probe, which lifted off in August 2018, has flown faster since. Despite its speed, it would take the probe nine-and-a-half years to make it from Earth to Pluto.

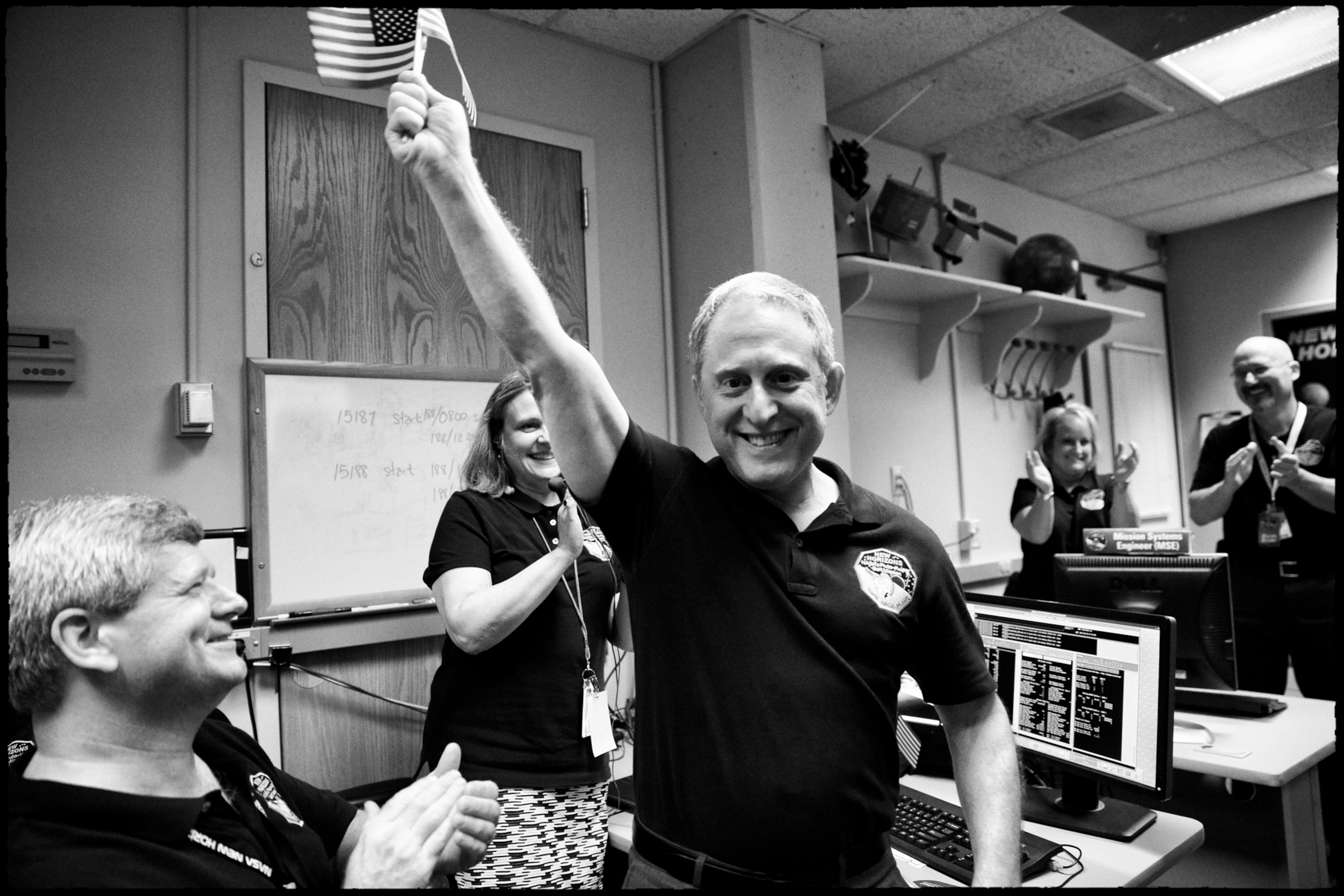

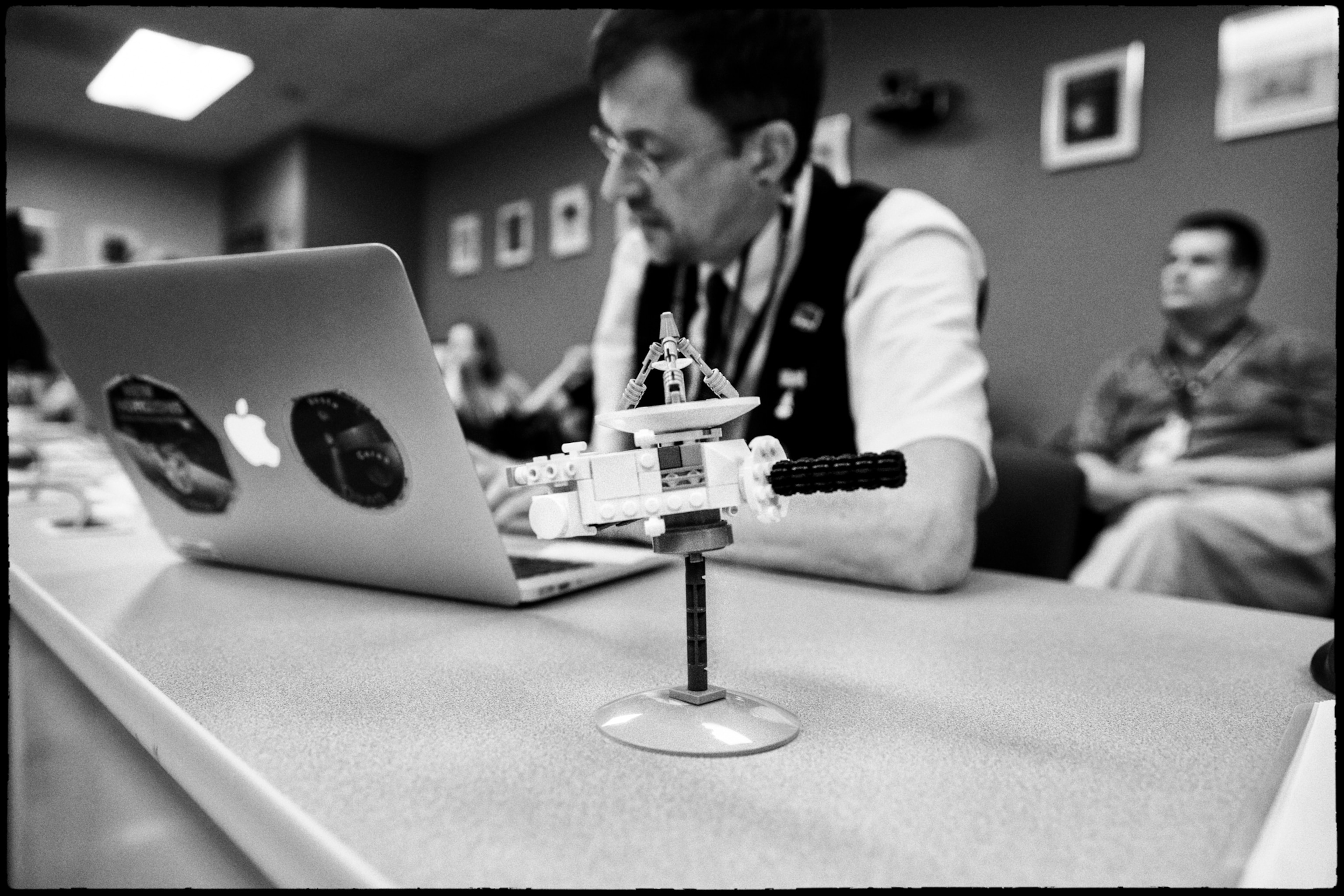

“Nine-and-a-half years was going to be the arc of my son, who at that point was just turning six years old. I realized he would be going into 10th grade [when New Horizons arrived],” says photographer Michael Soluri, who has documented the New Horizons mission since 2005. “The notion of time and distance became very profound for me.”

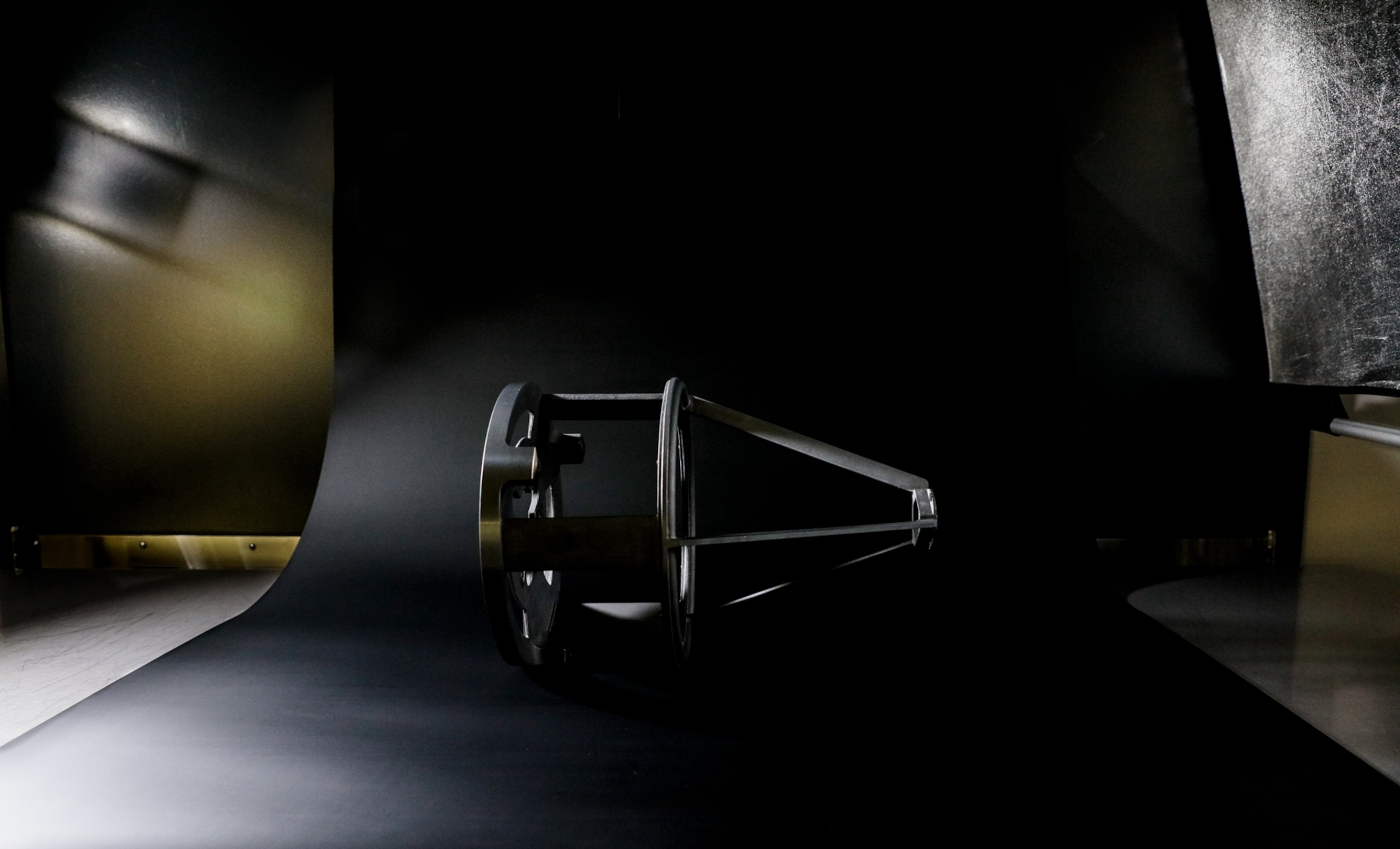

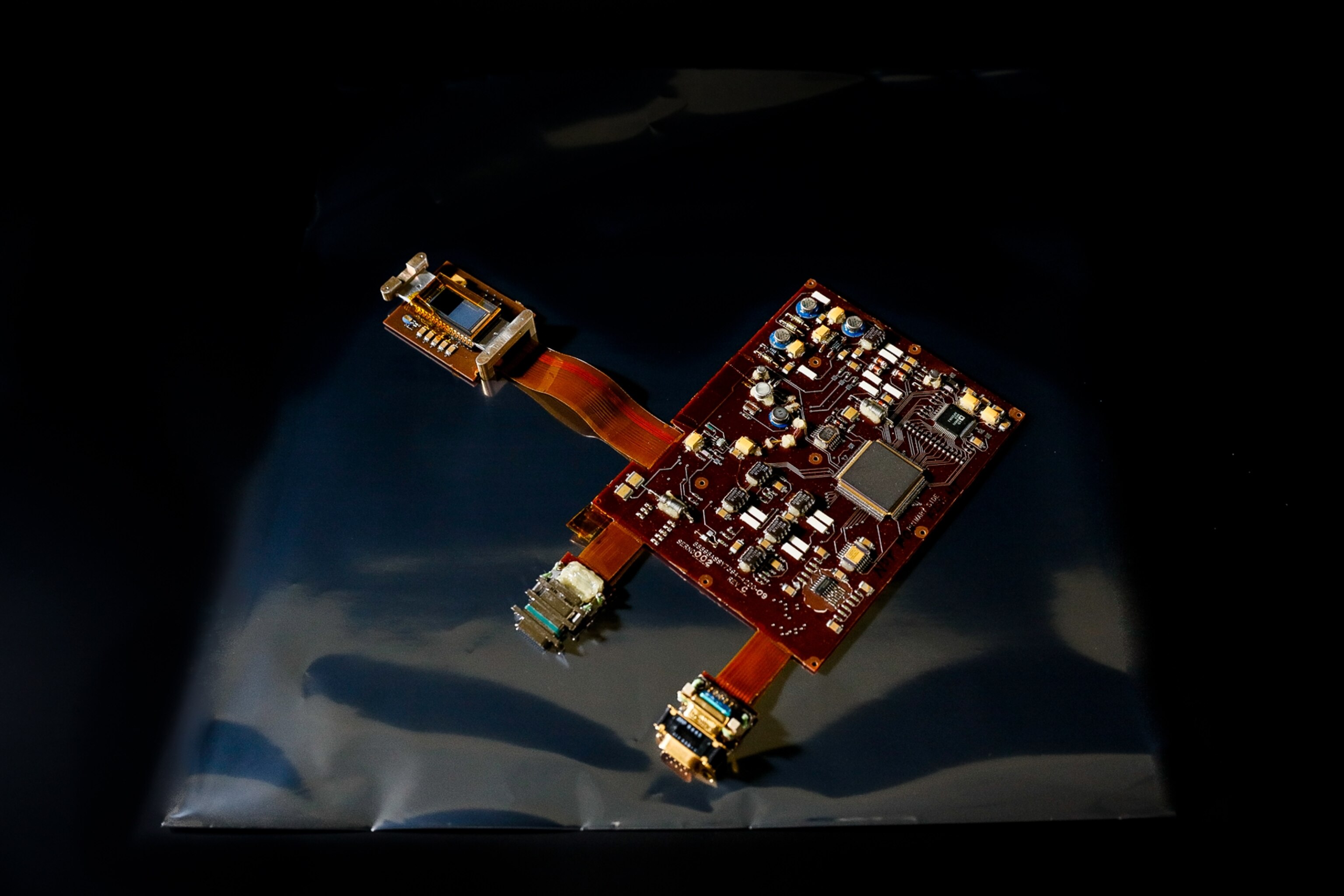

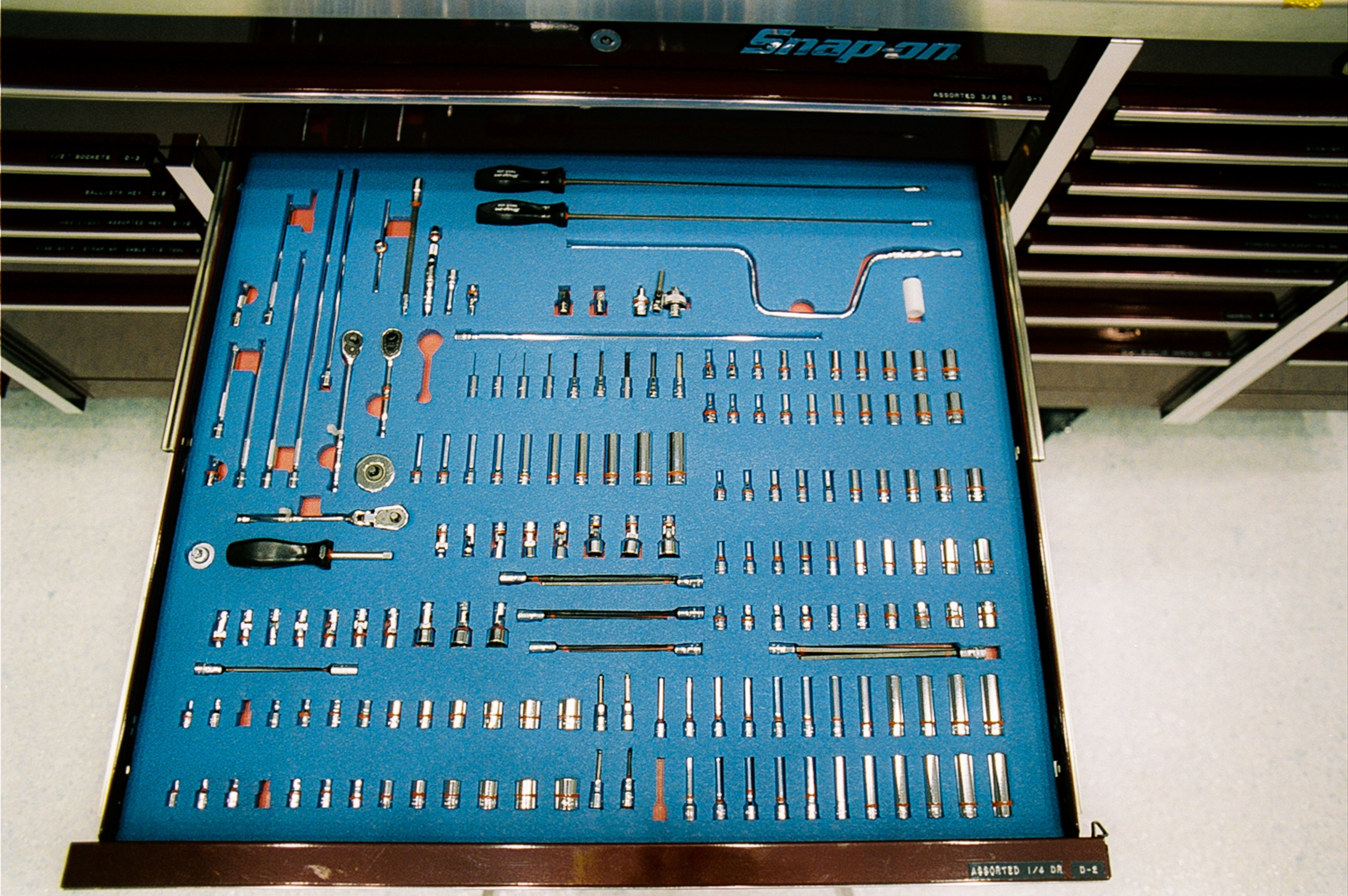

After reading Norman Mailer's reporting on Apollo 11, Soluri had long wanted to bring Mailer's eye for the human side of space exploration to photography. So he has spent years as a fly on the wall in Johns Hopkins University's Applied Physics Laboratory, the headquarters for the New Horizons mission, hopping from desk to desk with a single camera. Soluri—who once wanted to be a planetary geologist—likens the project to being in a college astronomy course.

“To get the one-on-one, and to get beyond the velvet rope, that takes a little homework,” he says.

Soluri's unofficial coursework has since stretched from Maryland across the solar system. Seventy-eight days after launch, New Horizons zoomed past the orbit of Mars. About seven months into the mission, the International Astronomical Union reclassified Pluto as a “dwarf planet,” kicking off 11 years of public debate. On February 28, 2007, the probe screamed past Jupiter, watching lightning flash in the gas giant's clouds and volcanoes erupt on Jupiter's fiery moon Io.

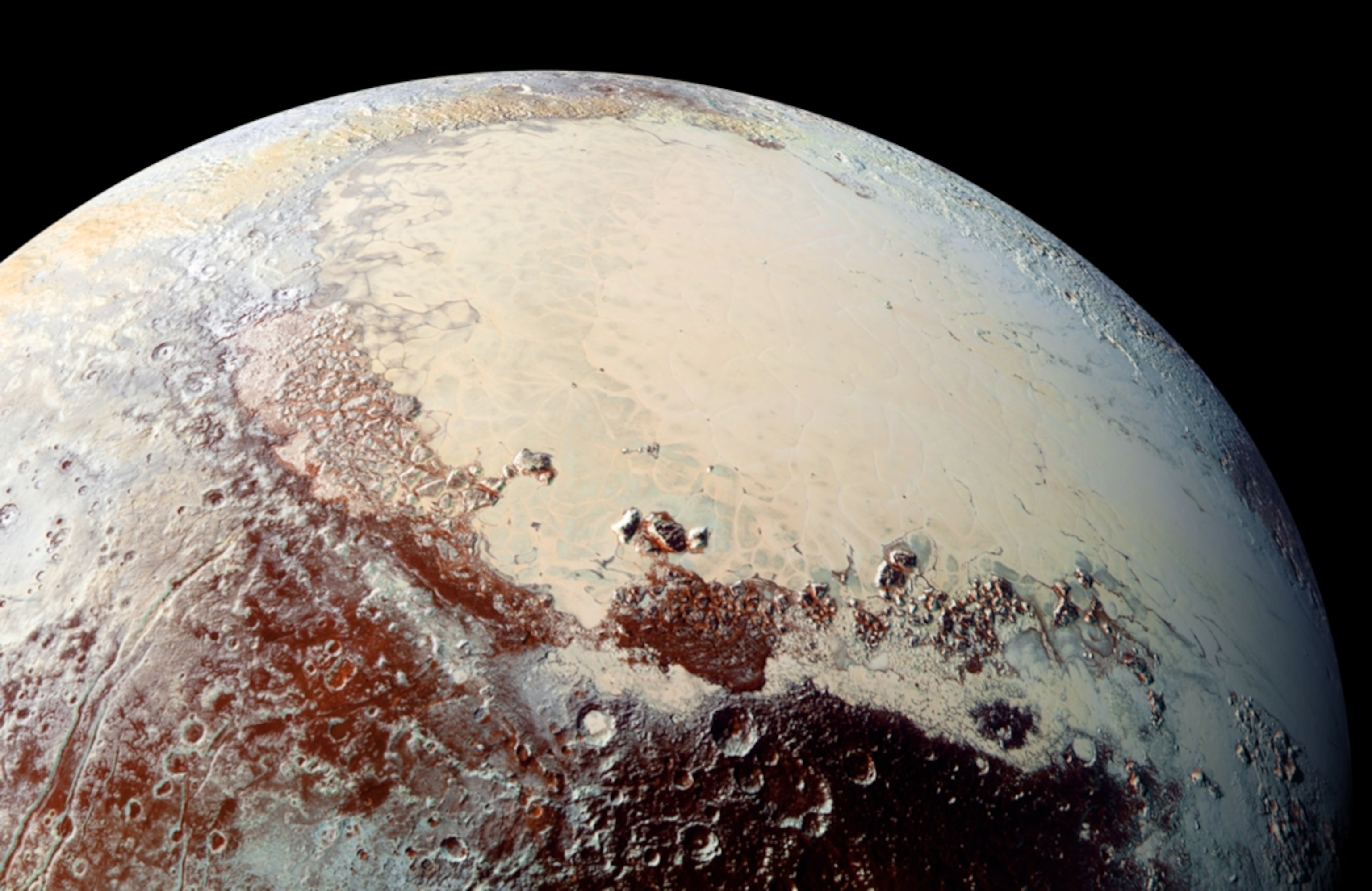

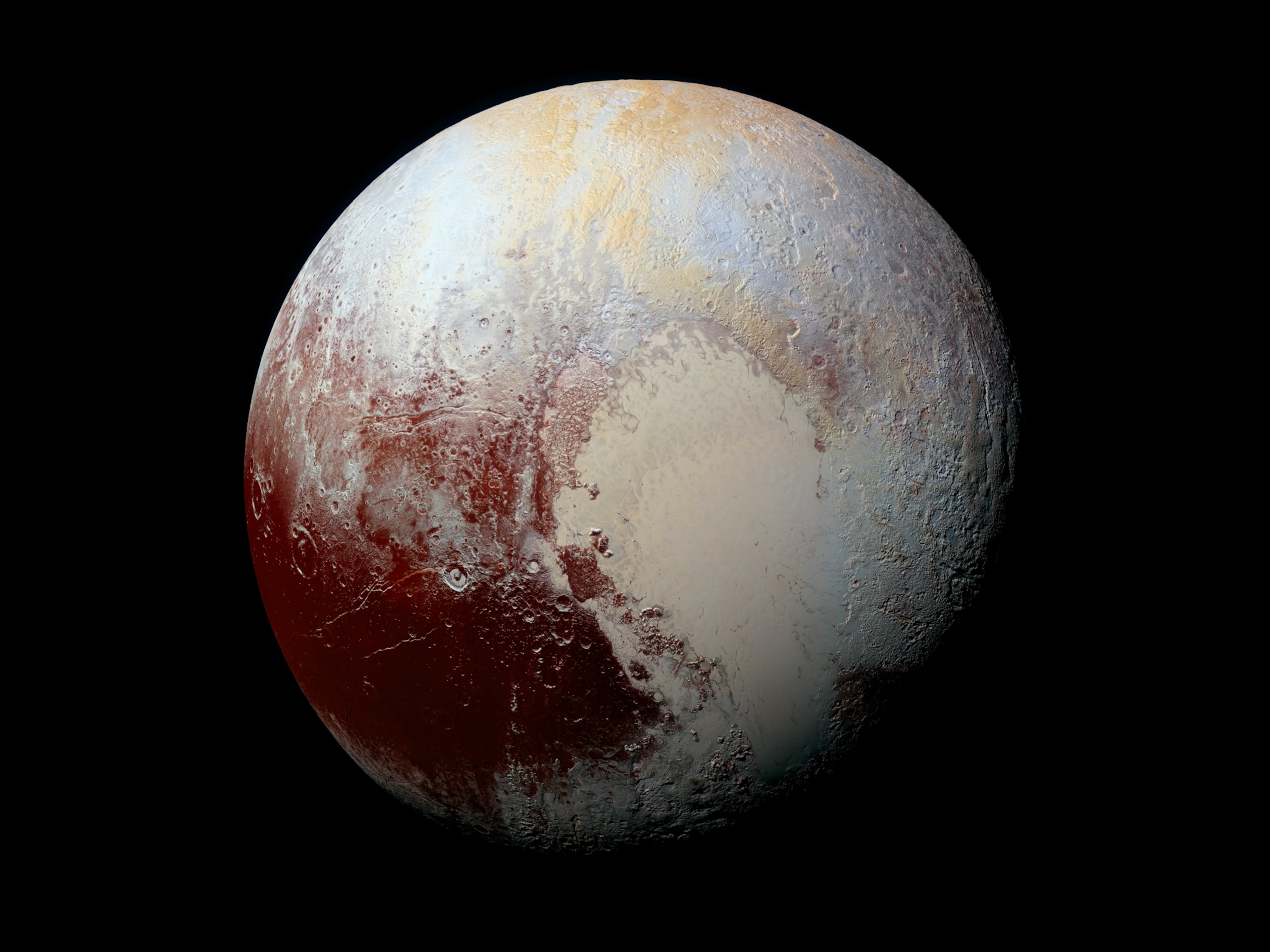

Finally, on July 14, 2015, Pluto became more than a faint dot in the sky. New Horizons images revealed one of the most geologically varied bodies in our entire system, with massive nitrogen plains shadowed by mountains—maybe even volcanoes—made of water ice. Pluto's moons also wowed, as researchers for the first time saw Charon's bloodstained north pole as well as Pluto's smaller satellites—Nix, Styx, Hydra, and Kerberos—dancing in a bizarrely chaotic fashion.

“It ... was long days,” Soluri says, but “I knew it would have meaning: This was the first reconnaissance of the Kuiper belt, and I was there with them as it happened.”

Gentle relics

Pluto was only the mission's first stop, however. As New Horizons made its way out toward its target, astronomers tried to see whether they could find another world to visit even further in the cosmos. In 2014, astronomers using the Hubble Space Telescope managed to discover some new Kuiper belt objects, three of which were within New Horizons' reach. The team decided that after the Pluto flyby, they'd point the spacecraft toward one of them, the object we now call MU69.

MU69 is a very different beast from Pluto by dint of being more ordinary. It's likely an inert ball of rock and ice roughly the size of New York City that resembles many other objects beyond Neptune's orbital path. As far as we know, it has kept largely to itself since the dawn of the solar system, orbiting the sun once every 297 Earth-years.

The body and others like it are sleepy objects that have circular orbits in line with the planets' orbital plane. They sail along in the same direction roughly parallel to each other, some moving at a human's walking pace. If and when these objects bump against each other, they do so gently. That means of all the bodies swirling through the solar system, MU69 and its kin are the likeliest to have gone 4.5 billion years without major disturbances.

“It's the oldest relic of the solar system we’ve ever studied,” says Southwest Research Institute astronomer Marc Buie, a member of the New Horizons team.

Seeing MU69 up close will help answer many questions. Its structure should help scientists figure out how gas and dust coalesce into planets in the first place. And because MU69 represents a bigger population, careful study of it should reveal more about its neighbors, including why many sport a unique reddish color.

New Horizons “takes one of these little dots in a population and makes it a world in its own right,” says Queen's University Belfast astronomer Michele Bannister. “I actually get to see one of these things as a place I could see with my own eyes. It's wonderful!”

'Exploration in the raw'

Before scientists can reap MU69's scientific bounty, though, they must successfully navigate the spacecraft to a target roughly four billion miles away. Since MU69 was discovered only four-and-a-half years ago, astronomers don't have a ton of data to help plot its orbital path. And since the object is so small and dim relative to Pluto, it's challenging to track it across the night sky—especially as the galaxy's bright stars shine in the background.

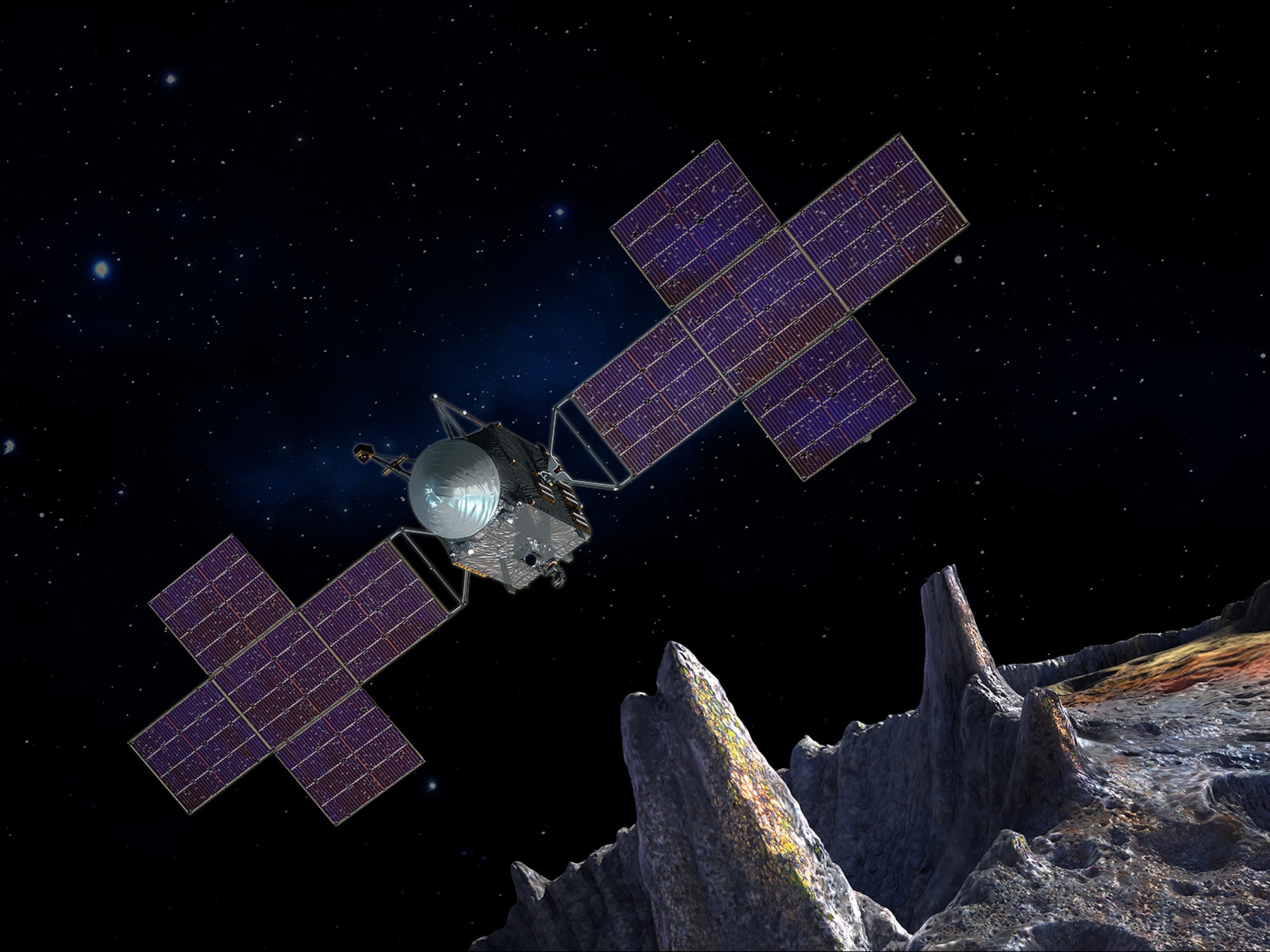

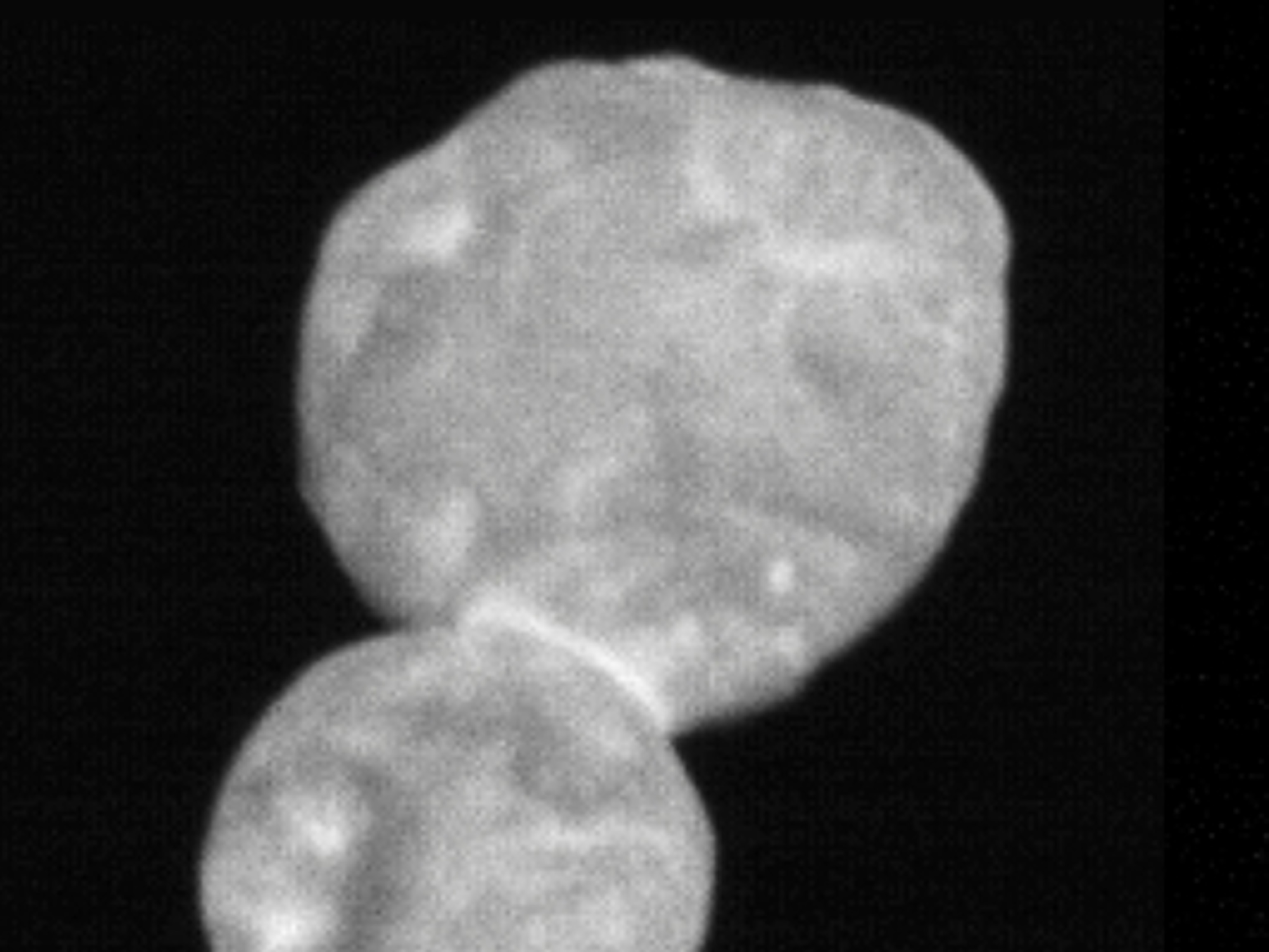

MU69's exact shape is also uncertain, though it's thought to be either two objects in close contact or one object shaped like a dumbbell. Recent Hubble measurements couldn't distinguish between the two scenarios. For the last few months, researchers have used New Horizons' best narrow-angle camera, LORRI, to take images of MU69 and to check for any hazards such as dust clouds. No threats to the spacecraft have been found, and the mission is currently on track to fly within 2,200 miles of MU69 at more than eight miles a second, snapping pictures all the while.

But if the object is rotating rapidly, New Horizons's images could get smeared with motion blur. It's also possible that LORRI will miss the world entirely.

“We might not have it in the frame, and that’s our very closest ride-along,” says New Horizons team member Amanda Zangari, a postdoctoral researcher at the Southwest Research Institute. “We're really going up to the limit.”

Whatever information the craft gathers, it will take New Horizons until 2020 to beam back all the data it collects. Next, mission scientists are holding out hope for an even grander vision: that New Horizons will become the first spacecraft to discover its own target and then fly by it.

“We’re setting a new precedent, right? We’ve never been to this part of the solar system,” says Planetary Science Institute senior scientist Susan Benecchi, a member of the New Horizons team. “It’s exploration in the raw.”