Cave ecosystems thrive in the dark. What happens when tourists light them up?

In Belize’s Actun Tunichil Muknal cave, a sacred Maya site, plants grow in darkness, sparking concerns about how tourism affects its fragile ecosystem.

Less than a mile inside Belize’s Actun Tunichil Muknal (ATM) cave, where sunlight rarely reaches, tiny green shoots cling to the limestone walls. Illuminated only briefly by the glow of tourists’ headlamps, these resilient plants defy expectations.

Most subterranean flora flourish near cave openings where daylight trickles in, but the plants in ATM thrive in total darkness. How is this possible?

How plants grow in the dark

Tour guides speculate that headlamps might play a role, mimicking the effect of artificial lighting in show caves. These lights often fuel the spread of lampenflora—communities of mosses, algae, and microbes that photosynthesize using artificial light.

However, ATM’s plants appear to grow naturally. Researchers suggest the seeds are brought into the cave by water or animals. “Any plant seed has enough energy to help that seed emerge onto the surface and then grow for a little while,” says Benjamin Tobin, director of the National Cave and Karst Research Institute.

Depending on the species, he says some plants require seeds to go through the digestive systems of animals, such as raccoons or ringtail cats. Bat guano, likewise, acts as an effective fertilizer, with seeds often deposited below bat roosts.

However, these plants can’t sustain growth. Despite the cave welcoming up to 250 visitors daily, the light from tourists’ headlamps is too brief and sporadic to maintain plant life. Without consistent light, the cave’s plants typically live for a few weeks in total darkness, says William Perez, a tour guide with Muy’Ono Resorts.

(Streetlights are influencing nature—from how leaves grow to how insects eat.)

But in caves with constant artificial light, the situation is quite different. As lamps flicker on stalactites and stone, they create a perfect environment for lampenflora to thrive—a phenomenon that is not only reshaping cave ecosystems but also introducing new challenges for conservation.

How show caves encourage lampenflora growth

In show caves, from Italy’s Stiffe Caves to the Great Basin’s Lehman Caves, permanent light fixtures emit enough energy for tourists to see and plants to eat, says Tobin.

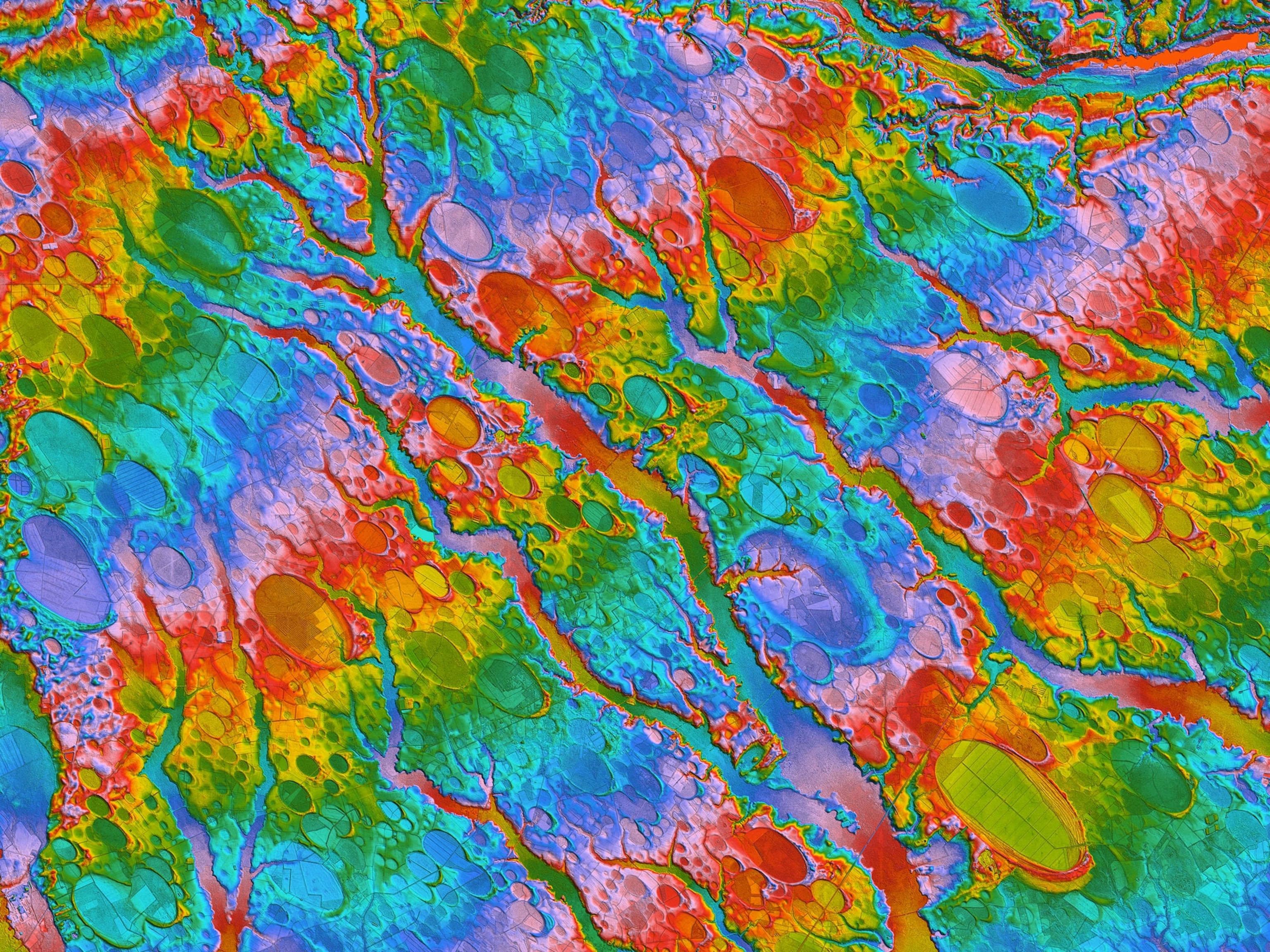

These well-fed lampenflora alter caves in appearance—the fuzzy green patches resemble bursts of moss—but they also corrode the surfaces of stalactites and introduce energy into naturally low-energy caves. According to biologist and researcher Giuseppe Nicolosi, their growth ultimately disrupts the equilibrium of fauna in subterranean ecosystems.

For example, even something as small as a tourist’s forgotten bag of snacks can introduce microbes and molds, throwing subterranean ecosystems out of balance, as seen in New Mexico’s Carlsbad Caverns National Park last September.

(Here’s why South Dakota is the “undisputed queen of maze caves“ in the U.S.)

Unfortunately, plants aren’t a cave’s only human-induced threat. “Just walking into a cave, we are shedding skin cells, we are shedding microplastics, and all of these things have impacts on the cave,” says Tobin.

Tourists also raise the level of carbon dioxide in caves, which interferes with limestone formation. Take France’s Lascaux and Spain’s Altamira caves, both of which were closed to visitors after the increase in carbon dioxide damaged invaluable paintings.

Such cultural risks are all the more layered in a show cave like ATM, which preserves Belize’s Maya history alongside ancient sites like Caracol and the “Crystal Maiden,” a calcified skeleton shimmering under headlamp light.

The Maya forest—one of the world’s most biodiverse tropical forests—is as endangered as the Maya culture, says Mesoamerican archeologist Anabel Ford. “I’d like to make monuments of ruins, not ruins of monuments,” she adds, suggesting a lighter touch to tourism.

(Tour the Maya underworld in these Belizean caves—if you dare.)

The Institute of Archaeology, which helps manage the ATM cave, recognizes these risks. In response to growing tourist interest, Belize’s government has implemented strict measures, including banning phones and cameras after a tourist dropped a recording device on an artifact. And starting in January 2025, ATM tours will limit group sizes to six people, down from eight, to reduce human impact.

Solutions to control lampenflora growth

Beyond Belize, scientific researchers are grappling with the challenge of lampenflora. Some have unsuccessfully experimented with different lamp colors and LEDs, while others have used herbicides for lampenflora removal. However, the plants are challenging to remove, and the latter approach can harm local fauna.

(Explore these 10 sacred caves around the world.)

The best solution is to avoid artificial lighting, says Nicolosi—or to follow the show cave strategy illuminated by ATM. “If there is a touristic path where people just walk and they don’t stay still [for] too much time, probably lampenflora is not able to grow, or at least you won’t see it,” he says. “Probably the best way to see show caves is to use the headlamp.”