Historic moon lander malfunctions after launch—but NASA isn’t panicked (yet)

A boxy robot that would have been the first American lunar lander to set down since 1972 suffered an anomaly, an inauspicious start to a series of high risk landings by untested private companies.

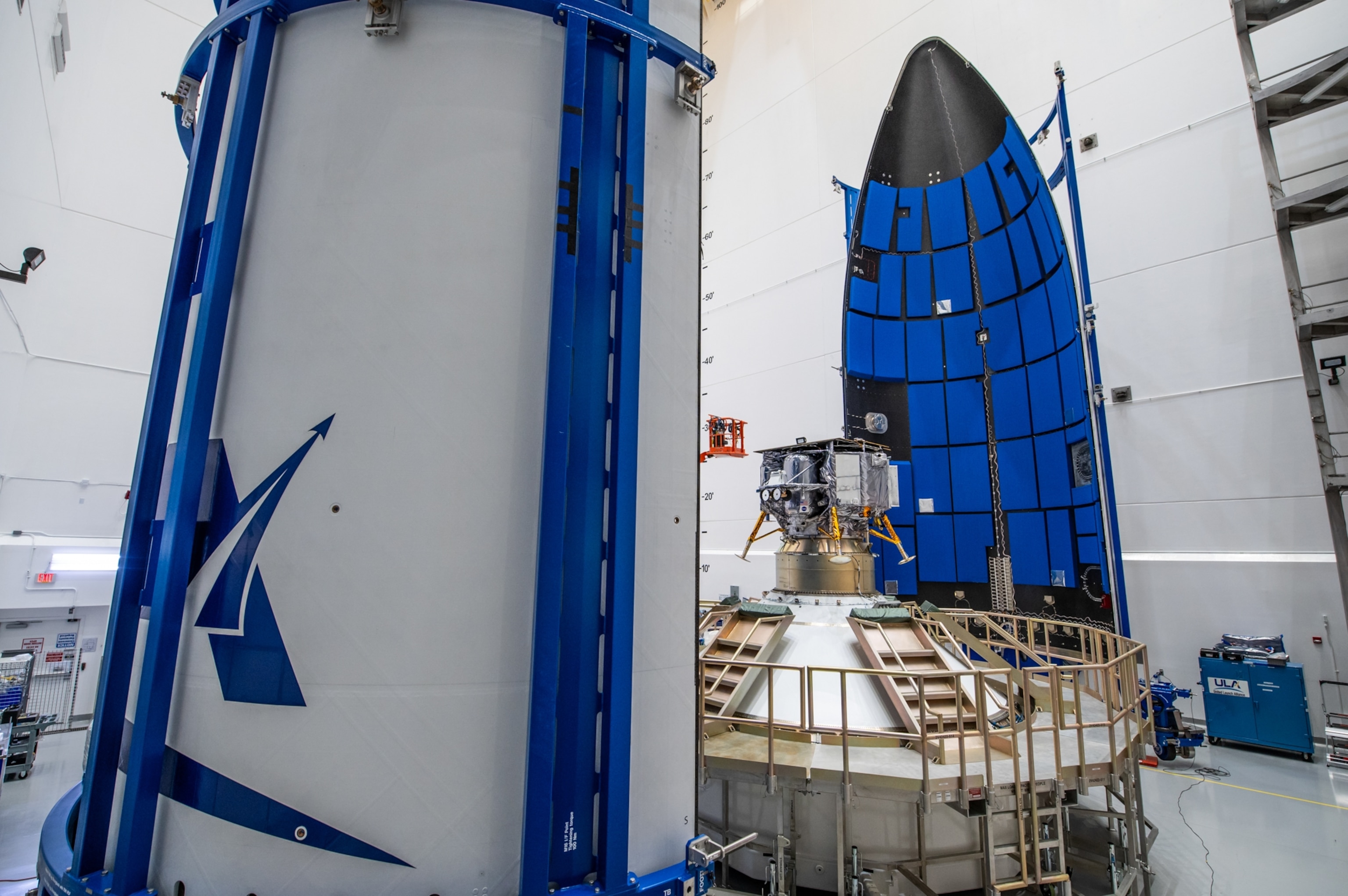

After a successful 2:18 a.m. ET launch from Florida this morning, a lunar lander built and operated by the space company Astrobotic suffered an engine malfunction and failed to correctly position its solar panels toward the sun. Controllers corrected the orientation of the spacecraft, but then confirmed it had a "critical loss of propellant," jeopardizing the craft’s mission to the moon.

The Peregrine lander, commissioned by NASA, was scheduled to land near the lunar south pole on February 23. If successful, it would have been the first American moon landing mission since Apollo 17’s arrival in December 1972, and the first lunar landing by a private company.

But shortly after the spacecraft separated from the upper stage of the rocket, controllers found they couldn’t orient the spacecraft toward the sun due to “an anomaly” with its thrusters that “threatens the ability of the spacecraft to soft land on the moon.”

“Each success and setback are opportunities to learn and grow,” said Joel Kearns, deputy associate administrator for exploration at NASA in a statement. “We will use this lesson to propel our efforts to advance science, exploration, and commercial development of the moon."

While a failure is bad news for NASA and the American commercial space industry, Peregrine’s launch marked the start of several privately run trips to survey the lunar south pole, the expected location for human missions under NASA’s Artemis program. Another lunar lander funded by NASA, built by Intuitive Machines of Houston, is scheduled to lift off next month, and Astrobotic has more attempts scheduled later this year.

“I want to tell you that I did sell this program consistently with a 50 percent likelihood [of mission success],” Thomas Zurbuchen, a former associate administrator at NASA who spearheaded the agency’s program to fund private lunar spacecraft, told National Geographic before the launch. The program, called Commercial Lunar Payload Services (CLPS), seeks to leverage private industry to deliver cargo to the moon, similar to how companies launch supplies to the International Space Station.

On top of several NASA instruments, the Peregrine lander carries cargo from seven countries on board. These include a radiation detector made by Germany’s space agency, five miniature rovers for the Mexican Space Agency, and small portions of human remains. The Navajo Nation objected to sending the remains, which include Star Trek creator Gene Roddenberry and science fiction author Arthur C. Clarke, because many Indigenous communities view the moon as sacred.

Now the spacecraft is not expected to make it to the moon, but other private missions are waiting in the wings. “My strategy was, CLPS is only in trouble after the third miss,” Zurbuchen said.

Send in the moonbots

In March 2018 NASA announced the CLPS program and began funding companies to design and build the next generation of affordable lunar spacecraft.

“What I was hoping when we came up with the idea was to create and develop a series of companies that could be available for Artemis,” says Zurbuchen, now the head of ETH Zurich, a public research university in Switzerland. “Remember, when you land on the moon and you want to stay there for a long time, cargo delivery is just as important as it is in the space station.”

The engineering challenge of a lunar landing is trickier than docking with the space station, and historically, many of the vehicles that have attempted to touch down on the moon have crashed. There’s no atmosphere to help slow down the spacecraft using parachutes, the pull of gravity increases speed on the way down, and much of the surface is strewn with boulders. Even in the sunlight, the shadows and glare can befuddle landing cameras and sensors.

Lunar landing attempts in recent years have included equal failures to touchdowns. Three Chinese spacecraft and the Indian Chandrayaan 3 lander set down safely on the lunar surface, but additional landers from Israel, India, and Russia, as well as a private Japanese spacecraft, each crashed.

Having multiple landers in operation is central to the idea of CLPS. Instead of funding a single craft built to rigid standards, the program seeded several companies to create their own landers and accepted a higher risk of failure. “We deliberately took a light touch,” Zurbuchen said of NASA’s engineering oversight.

A new way to explore the moon

The CLPS program was a welcome development for Astrobotic. The Pittsburgh company was founded in 2007 by Carnegie Mellon professor Red Whittaker with a sole goal of winning the Google Lunar X-Prize. To claim the $20 million bounty, a private company had to land a rover on the moon that could travel about 1,600 feet and transmit high-definition images to Earth.

By 2018, no one had done it. But NASA’s new program to fund lunar landing companies came just as the X-Prize was winding down. Astrobotic won its first CLPS contract in May 2019, making decades of work relevant again. “CLPS was a very big deal for us,” John Thornton, CEO of Astrobotic, said before the company’ first launch. “We were working towards a prize that couldn’t fund the mission.”

Two other companies also won the initial CLPS contracts—one went out of business, but Houston-based Intuitive Machines’ Nova C lander is ready to launch next month. Before CLPS, “nothing was being developed here in terms of lunar programs, and now we have our first mission,” Intuitive Machine’s CEO Steve Altemus told National Geographic late last year. “In the time it takes to get an undergraduate degree, we built a whole lunar program.”

With the first CLPS launch attempt, the United States enters an ongoing, worldwide return to the moon. Over the next ten years, space agencies and companies in the U.S. and other countries are planning scores of missions to the lunar surface.

“Frankly, it’s not clear yet how it’s going to work out,” conceded Zurbuchen before the launch. “It’s a huge leap, but one that we’re ready for, I think.”