How COVID-19 vaccines are getting to the world’s remotest places

Devoted teams of health-care workers are trekking great distances to deliver the life-saving inoculations.

Nazir Ahmed stands on a hilltop in the Indian territory of Jammu and Kashmir gazing at the rolling green landscape that unfolds before him. The health-care worker scans a nearby valley, searching for shepherds tending their sheep by the meandering branches of the river below. Dangling by his side is a bright blue cooler, a vibrant reminder of Ahmed and his team's urgent task: Deliver as many COVID-19 vaccinations as possible.

The team is among many groups who are trekking, boating, dogsledding, and more to deliver vaccines to people in the most remote corners of the world. No matter how secluded, all communities are at risk from the deadly virus. The question is not if it will arrive: "The virus has already reached these areas," says Miriam Alía Prieto, the vaccination and outbreak response advisor at Doctors Without Borders.

While the total number of COVID-19 cases in remote areas is small compared to big cities, the risks of a coronavirus infection are much more severe, Prieto explains. Many rural dwellers have limited or no access to intensive care facilities or supplemental oxygen—one of the few ways to help patients as the disease infiltrates their lungs. Prieto recalls a recent five-day boat trip through the rivers of Peru to deliver cylinders of oxygen to a community in need.

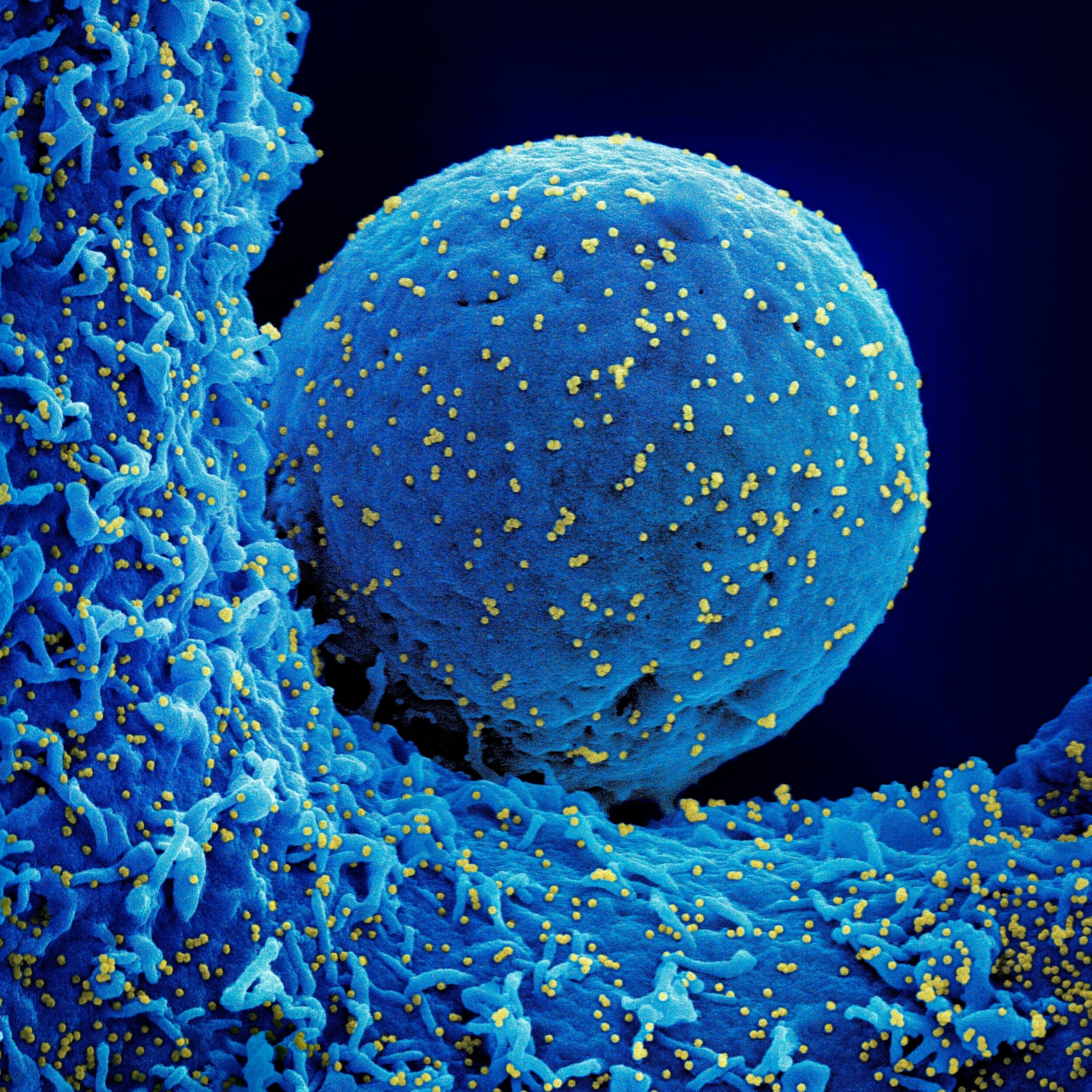

What's more, the slew of variants racing around the world has laid bare the risks of allowing the coronavirus—or any virus—to spread like wildfire. The more people who become infected, the more chances the virus has to accrue mutations, potentially shapeshifting into more formidable foes. The mantra that much of the health-care community adopted early in the pandemic is now truer than ever: No one's safe until everyone's safe.

This is not the first time health-care workers traveled far and wide to deliver vaccines, but the scale and urgency of the current vaccination efforts are unlike any in modern memory. "We've never had a vaccine-preventable pandemic before," Prieto says.

Steep challenges and steep terrain

The challenges with distributing vaccines started bubbling up long before the shots were approved, when wealthy countries placed big orders from pharmaceutical companies and shoved others to the back of the distribution line. Around 4.6 billion vaccine doses have been administered around the world as of August 13, and about 31 percent of the world's population has gotten at least one dose. But a paltry 1.2 percent of those people are in low-income countries.

Many African countries, for instance, don't yet have enough doses to fully vaccinate frontline workers, Prieto says. In the Democratic Republic of the Congo, a nation of 89.6 million, vaccination is yet to reach one dose per 100 people.

The COVAX alliance—a joint effort led by the World Health Organization, Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance, and the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations—launched in April 2020 with a bold mission to ensure all countries have fair and equitable access to the COVID-19 vaccine. Yet the organization has struggled to collect enough vaccines and funding to effectively get shots into arms.

Bringing the vaccines to rural communities poses even more challenges. In countries where vaccines are scarce, new shipments are often used up in large cities before doses can trickle out to surrounding regions and rural communities, Prieto says.

In some places, particularly in middle- or upper-income countries, the doses are slowly moving out to people that live far from city centers. In the U.S., for example, a series of airplanes, water taxis, and even dogsleds helped ferry vaccines to rural Alaskan communities and Native people, who are particularly at risk for severe COVID-19. Teams in Colombia have also run vaccination drives in rural communities to ensure elderly people are immunized.

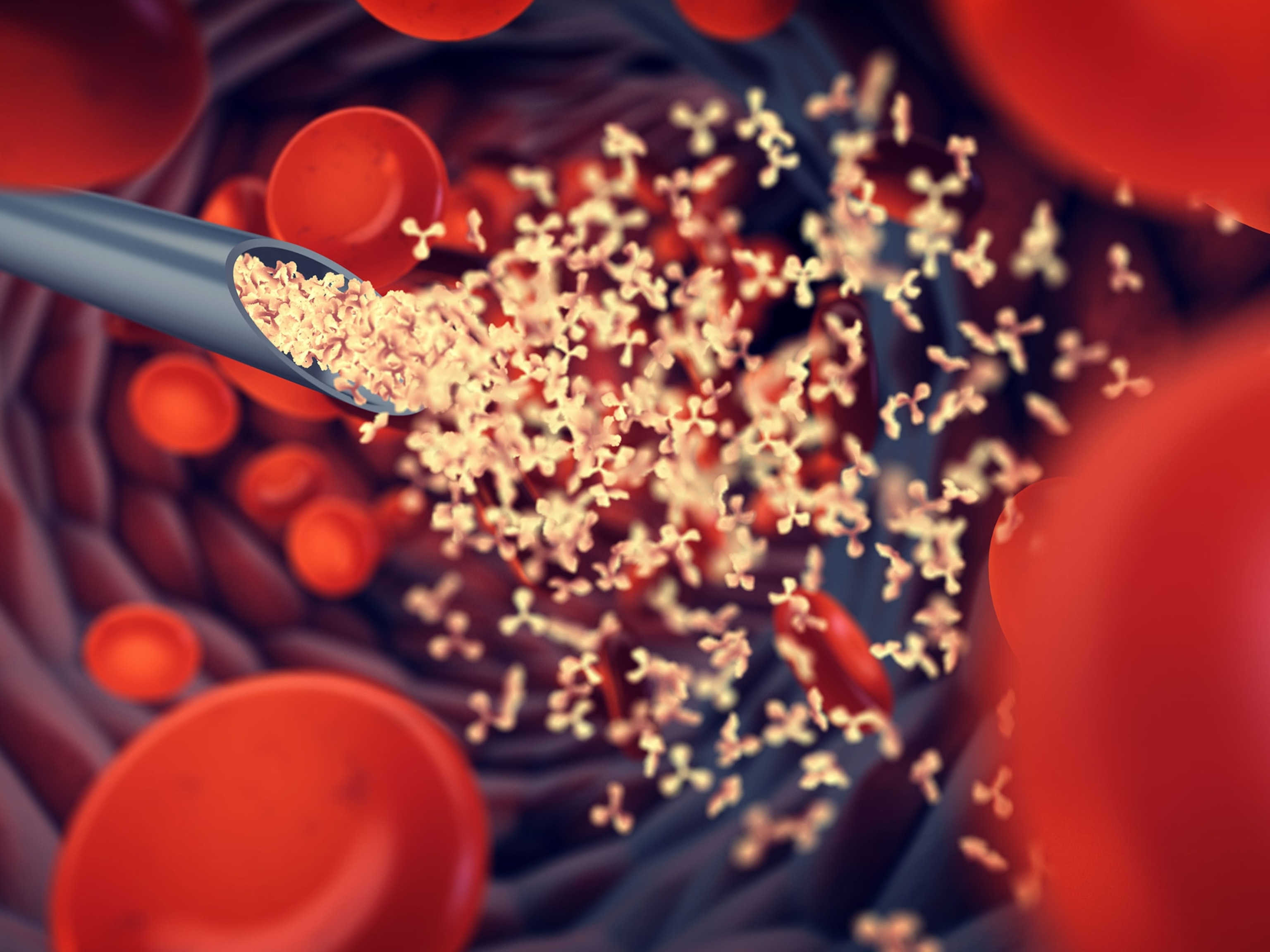

All of these efforts, however, face a common hurdle. The COVID-19 vaccines—similar to many other immunizations—have to be kept cold nearly until they're injected, which requires an expensive series of temperature-controlled shipments and storage, known as the cold chain. But electricity is often inconsistent or absent the further from cities that teams travel.

To keep vaccines cool, the transporters pack the shots in coolers with ice packs. The coolers then must be kept safe en route. They are often strapped to the back of motorbikes, Prieto says, but if the roads become impassable, teams must forge ahead on foot. Sometimes the coolers are suspended on poles between two people walking, she adds.

For all these efforts, the clock is always ticking. If the cooler remains closed, teams usually have around three to five days before the shots need to be used or the ice packs replaced, Prieto says.

Another challenge for rural COVID-19 vaccinations is that the shots require the presence of health-care workers to give the injection. That differs from past vaccination efforts for other diseases, such as cholera or polio, that can be controlled with oral immunizations that require no special training to dole out. Prieto notes that this is likely the reason behind the eradication of polio in Africa. "You go door-to-door with people from the community—mothers, teachers—you don't need medical staff," she explains.

Yet health-care workers have risen to the challenge for COVID-19. To capture this herculean task, National Geographic selected images from around the world showing just how far health-care workers have been willing to go to help bring this pandemic to a swifter end.