How NASA’s Artemis program plans to return astronauts to the moon

The lunar campaign begins with the test flight of a giant new rocket, followed by missions to fly humans to the moon for the first time since 1972.

In just the next few years, NASA aims to land the first astronauts on the moon since 1972, including the first woman to voyage to the lunar surface. Following in the footsteps of the Apollo program, this 21st century lunar campaign, called Artemis, could return humans to the moon’s surface as soon as 2025.

Named after the Greek goddess of the moon, the Artemis program was created to fly repeated trips to the moon so that NASA and its partner space agencies can establish a new foothold off-world. NASA officials also hope that Artemis will serve as the first step toward even greater ambitions in space, such as establishing a regular lunar presence and venturing all the way to Mars.

The path back to the moon is a complex one with many remaining challenges, but extraordinary opportunities for exploration as well. Here’s the plan to land back on the lunar surface, the technology required to complete such a mission, and what we know about who may be selected to make the lunar odyssey.

What spacecraft are used in the Artemis program?

During their missions, the Artemis crews will live aboard Orion, a capsule designed to keep a crew of four alive and healthy in deep space for up to 21 days. Each Orion capsule will fly with a European Service Module, provided by the European Space Agency, that will carry solar panels, life support systems, fuel tanks, and the main engine needed to enter lunar orbit.

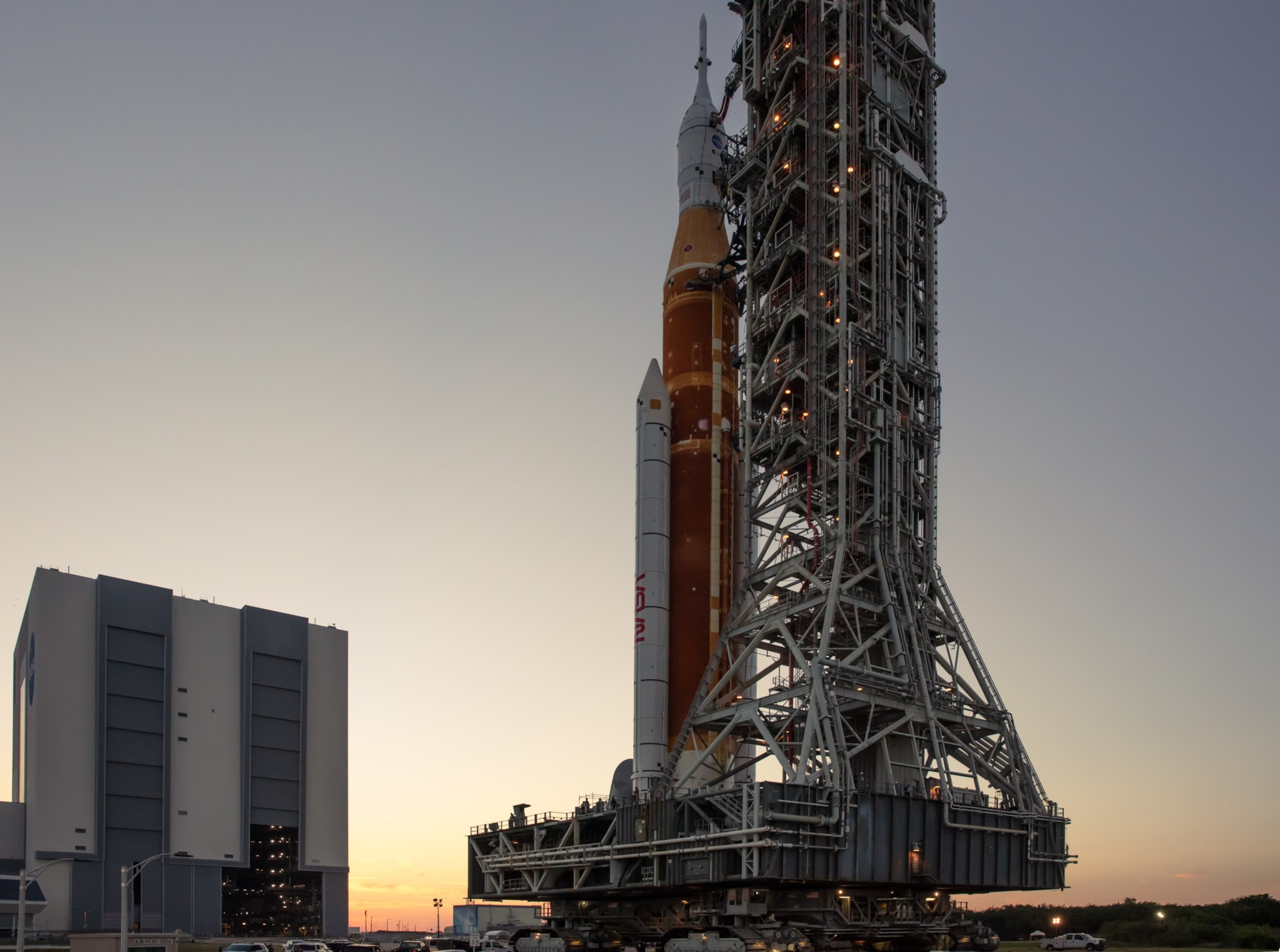

Orion’s ride to the moon is the Space Launch System, or SLS: a 322-foot-tall rocket with a core stage that burns a mix of liquid hydrogen and liquid oxygen. The jumbo rocket’s first stage uses four RS-25 rocket engines, originally developed for the space shuttle program. Artemis I, an uncrewed test flight to the moon and back, will use refurbished engines that have each flown on at least three space shuttle missions.

Each SLS rocket will also use two massive solid-fuel boosters attached on either side of the core stage. Combined, the rocket will generate 8.8 million pounds of thrust at launch, 15 percent more than the Apollo program’s Saturn V. The rocket’s upper stage will detach from the core stage once it reaches space and fire its own engines to send Orion (with the European Service Module) on its way moonward.

Orion can’t land on the moon itself, so when NASA makes its lunar landing attempt during Artemis III, it will transfer the crew from Orion to a modified version of SpaceX’s Starship spacecraft while in lunar orbit. Starship, which SpaceX is currently testing, will then ferry the astronauts to and from the lunar surface.

Once Orion returns to Earth, the gumdrop-shaped capsule will use its heat shields to survive the blazing descent through Earth’s atmosphere and then deploy parachutes for an ocean splashdown.

What are the first missions of the Artemis program?

The first mission, called Artemis I, is an uncrewed test launch that will fly as soon as November 16, with backup dates on November 19 and 25. Artemis I will be the first uncrewed flight test of the whole vehicle “stack”: Orion, the European Service Module, and the SLS rocket. The only piece that has flown in space before is Orion, which launched on another rocket in December 2014 to test its heat shields. This first mission will last four to six weeks, depending on when it launches, taking Orion into orbit around the moon and then back to Earth.

“We're learning through the challenges, the accomplishments: Artemis I shows that we can do big things, things that unite people, things that benefit humanity, things like Apollo that inspire the world,” NASA administrator Bill Nelson said in an August 3 media briefing. “This is now the Artemis generation.”

Artemis II, slated for no sooner than May 2024, will be the program’s first crewed flight. During this 10-day mission, a crew of four will fly by the moon aboard Orion and then return to Earth. The mission resembles the December 1968 flight of Apollo 8.

Artemis III, the mission meant to return people to the lunar surface, will launch no sooner than 2025. This four-astronaut mission will begin much like Artemis II, but when Orion reaches the moon, it will dock with a waiting Starship vehicle from SpaceX. Two members of the crew will then use Starship to land on the moon’s surface near the lunar south pole. Those astronauts will spend about 6.5 days exploring and doing research, and then Starship will ferry the crew back to lunar orbit, where the astronauts will return to Orion and head back to Earth.

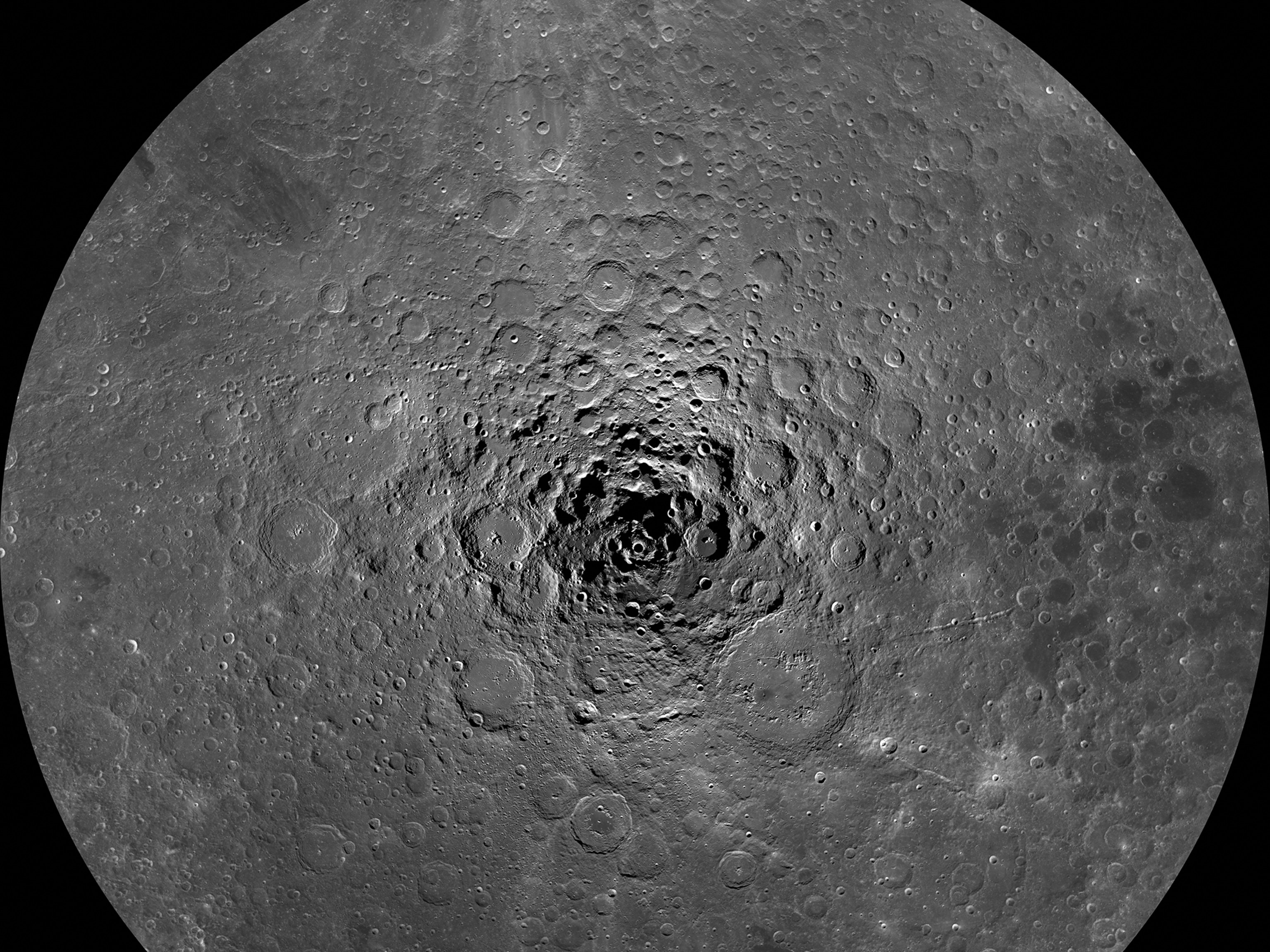

Where will Artemis III land on the moon?

Unlike the Apollo missions, which landed near the moon’s equator, Artemis III will land near the moon’s south pole. NASA has unveiled 13 candidate landing regions. Each one is roughly a 9.3-mile-wide square and contains at least 10 possible landing sites.

NASA is considering these sites because they include diverse geologic features that haven’t been explored before. Each site has flat terrain for a safe landing and gets 6.5 days of sunlight at a time, allowing the astronauts to remain on the surface for nearly a week. The areas spend other periods of time covered by shadow, so the exact landing site of Artemis III will depend on when the mission launches.

The lunar rock and dust (known as regolith) within permanently shadowed areas near the target landing sites contain the chemical fingerprints of water. Harvesting water ice from the lunar regolith would make it much easier to establish a long-term human presence on the moon, such as an Antarctica-style research station.

However, it’s not yet known whether the water inside this dust is plentiful or easy to extract. To find out if the water in the region is usable, NASA plans to send a robotic rover called VIPER to explore the lunar south pole as soon as 2024 to gather more data on the ice deposits.

How did the Artemis program come to be?

The roots of Artemis go back to the Constellation spaceflight program under President George W. Bush, which was formalized in 2005 and became NASA’s human spaceflight program to replace the retiring space shuttle.

Under the Obama administration, the Constellation program was canceled amid concerns that it was facing delays and cost overruns—a move that threw the aerospace industry that had built up around the space shuttle and Constellation into murky waters. In 2010 Congress responded by passing a bill that kept the Constellation crew capsule Orion and called for a new rocket that made use of existing space shuttle and Constellation contracts, which would become SLS.

Plans for Orion and SLS have evolved over the years, but the Artemis program as we know it today was organized under the Trump administration, with a renewed focus on returning to the moon as a stepping stone to Mars. The Biden administration has kept Artemis largely unchanged, delaying the target date for a lunar landing to 2025 from 2024.

How much does the Artemis program cost?

From fiscal year 2012 to 2025, Artemis-related programs will cost an estimated $93 billion, and the first Artemis launches are estimated to cost $4.1 billion each, according to NASA’s Office of the Inspector General. Costs for Artemis have ballooned past initial estimates, to the point that NASA Inspector General Paul Martin called them “unsustainable” earlier this year.

So far, Congress has remained committed to funding Artemis. Slightly less than half of NASA’s annual budget is devoted to human spaceflight, and NASA’s total budget currently amounts to 0.4 percent of federal discretionary spending, according to the Planetary Society, a space advocacy nonprofit.

Are other countries involved?

Though Artemis is a U.S. program, NASA officials have invited other countries to join the effort. Canada and Japan have committed to helping build a future space station around the moon known as Gateway. NASA also has signed the “Artemis Accords” with Canada, Japan, and at least 18 other countries, a set of nonbinding agreements that set out principles for peaceful cooperation in space.

Who will be selected to go to the moon?

No astronauts have yet been named for crewed Artemis flights, but NASA officials have said that the entire NASA astronaut corps is eligible to fly on Artemis missions. NASA has also announced that a Canadian astronaut will fly aboard Artemis II in exchange for Canada’s investments in the program.

In addition, NASA has committed Artemis III to landing the first woman on the moon. The agency also says that it will land the first person of color on the surface of the moon, either on Artemis III or on a future mission.

Why are we sending people to the moon?

NASA and other space agencies have renewed their lunar ambitions because the moon provides a scientifically rich and relatively close destination for planetary exploration. As samples returned by the Apollo missions have revealed, the moon’s soils and impact craters act as a library that chronicles the solar system’s 4.5-billion-year history.

Earth’s natural satellite could also serve as a training ground for missions to other parts of the solar system. Though the moon and Mars differ in many ways, lessons learned at the moon—building shelters, flying through deep space, and extracting water from ice deposits—could inform eventual human exploration of Mars.

Advocates of human spaceflight also believe the challenges of exploring beyond Earth can have broader benefits. Large technological endeavors such as Artemis and the International Space Station provide an opportunity for countries to work together in peaceful ways. Building the hardware and software for Artemis will provide jobs for a large, highly skilled workforce. To some, Artemis’s goal of returning to the moon also serves as an important inspiration for young people to learn about science and technology.

For University of Notre Dame lunar scientist Clive Neal, whether Artemis can be considered a success or not depends on the technological benefits that it yields. He points to the Apollo program’s guidance computer, which gave a boost to the fledgling silicon chip industry. “The endgame should be to make life better down on this planet,” he says.

What happens after Artemis III?

The future of Artemis will ultimately depend on the will of Congress and the American people. For now, NASA is planning repeated missions to the moon’s surface. Components of SLS and Orion are already being built for Artemis IV.

Additional pieces of Artemis infrastructure are also well underway. In a partnership with the Canadian and Japanese space agencies, NASA is building the Gateway space station to orbit the moon. This craft is meant to provide a staging ground for future sorties to the lunar surface. Parts of the Gateway are already being built, and its first two modules could be launched as early as 2024. The Artemis IV mission—which will launch no sooner than 2026—is slated to finish the Gateway’s assembly in lunar orbit.

NASA has sketched out ideas for other potential activities on the moon, including a “LunaNet” telecommunications network, a habitat on the lunar surface, and a large pressurized rover. But these visions of continuous human habitation on the moon depend on the success of the first few Artemis launches—which will put the world’s newest moon rocket and spacecraft to the test.