On a clear December morning, a team of scientists followed a homing beacon into the remote Australian desert to collect precious material from outer space. The shoebox-size capsule, part of Japan’s Hayabusa2 mission, held rocks and dust from Ryugu, a carbon-rich asteroid that likely harbors the building blocks of life. To keep the sample pristine, the capsule was whisked away to the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency’s (JAXA) Extraterrestrial Sample Curation Center, a lab near Tokyo designed to prevent the cosmic material from being contaminated with earthly organisms.

For years, concerns about planetary protection have focused on preventing Earth from littering the solar system—sterilizing spacecraft and keeping astronauts under strict quarantine protocols. But as space agencies around the world gear up to bring more samples back from destinations such as asteroids, the moon, and Mars, scientists are once more considering the opposite prospect: What if we bring extraterrestrial germs back to Earth?

At one time, scientists treated all unearthly samples as potential biohazards. NASA once quarantined Apollo astronauts when they returned from jaunts on the lunar surface. As the agency studied lunar samples and discovered that they didn’t contain life, they did away with many of these safety protocols.

But as multiple sample-return missions head into higher gear, extra caution is once more warranted. In recent years, scientists have found hearty microorganisms that can survive in ever more inhospitable places. Diminutive tardigrades, also known as water bears, can even survive in the vacuum of space.

“Here on Earth, for example in South African gold mines, when you drill through a rock, sometimes you come across a reservoir of water that's been there hundreds of thousands of years, and there are microbes in it,” says J. Andy Spry, a senior scientist at the Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence Institute. “If you provide them with heat, and light and warmth—they will grow.”

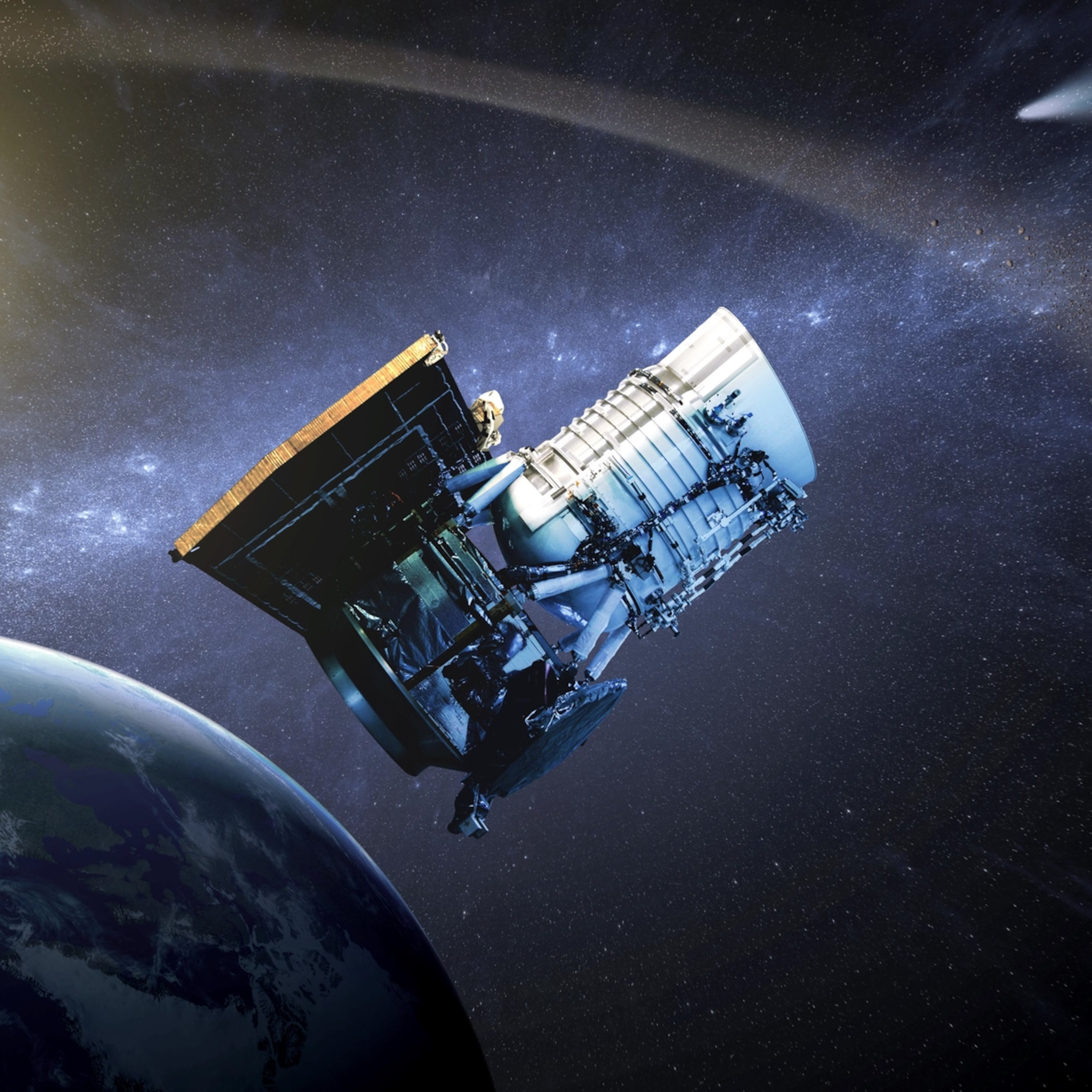

In addition to the fresh samples from Ryugu, a NASA spacecraft will bring home pieces from the carbon-bearing asteroid Bennu in 2023. And in February, a NASA rover called Perseverance is expected to land in a region of Mars that might have preserved traces of life, if any once existed on the red planet. Crucially, the rover will collect and store samples of Martian rocks that will ultimately be sent back to Earth—perhaps carting home extraterrestrial companions.

“Our understanding of Mars is that absolutely there may have been life in the past,” says Spry. “There may still be viable life in reservoirs under the planet’s surface.”

So, space agencies around the world, including NASA, JAXA, and the European Space Agency (ESA), are working together to create new highly secure labs designed to protect Earth from whatever microbes or organic residue future missions might bring home. These labs will combine current cleanroom technology with the high-security biosafety protocols and equipment used by infectious disease laboratories to safely handle plagues such as Ebola and SARS-CoV-2.

“The Mars sample return campaign, which is currently underway, has gone to elaborate ends to encapsulate the samples that Perseverance will collect,” says Scott Hubbard, the former deputy director for research at NASA’s Ames Research Center in California’s Silicon Valley, where he oversaw programs for astrobiology and Mars missions.

“When that cannister lands in 2031 in the Utah desert, it will be carried to a facility with the highest biosafety level protections.”

When astronauts quarantined

NASA, at least, can look to its past for inspiration on these laboratory designs. When the Apollo astronauts returned from the surface of the moon, their spacesuits were covered in lunar dust. NASA hadn’t yet studied the composition of pristine moon rocks, so the agency treated all particles from the lunar surface as potentially dangerous to human life.

NASA quarantined crews from Apollo missions 11, 12, and 14 in a modified AirStream trailer on the deck of the aircraft carrier that plucked them from the ocean in their floating capsule. Once ashore, a helicopter whisked them to the Lunar Receiving Laboratory at Lyndon B. Johnson Space Center in Houston, Texas, the precursor to facilities currently in development around the globe.

At the Lunar Receiving Laboratory, crews would spend their first 21 days back on Earth in the Crew Reception Area, which sealed them inside a biological barrier to prevent “back-contamination,” what NASA called the possible spread of lunar microorganisms on Earth. The facility also included the Sample Operation Area, which housed vacuum gloveboxes and equipment for biological analyses.

The most important part of the Lunar Receiving Lab’s biosecurity scheme was its complex vacuum system, which had to block outside contaminants from coming in, as well as keep potential lunar microbes from circulating or getting out. The elaborate design of pumps and valves, in total the size of a double-decker bus, occupied its own warehouse room and included a back-up vacuum system in case the first failed.

This lab would later become part of NASA’s Astromaterials Research and Exploration Science Directorate, also at Johnson Space Center, which maintains specimens of stardust, meteorites, and comet particles in addition to the Apollo moon rocks. All of this material is housed in positive-pressure cleanrooms similar to those used in the semiconductor industry. Positive pressure means that air is always flowing out of the room, so the inside stays sterile.

However, these systems are less complicated than the ones needed for receiving Mars samples and other new specimens, because they don’t need to keep any potential microbes contained.

The labs being built “will essentially use containment inside of containment,” says Michael Calaway, a NASA contractor from the Jacobs Engineering Group and a sample curation project leader for ARES. And to do that, designers are seeking lessons from the highest biosecurity labs on Earth.

Building the world’s most secure laboratory

In Boston, the National Emerging Infectious Diseases Laboratories (NEIDL) have gone on lockdown. A pathogen spill has put the facility on red alert. Researchers and staff follow their orders to quarantine as first responders arrive.

Everyone is calm, of course, not just because they know what they’re doing—but because the spill isn’t real. It’s a drill, part of the protocol that keeps NEIDL safe and helps maintain its distinction as one of the most secure laboratories in the world.

It’s Ronald Corely’s job to imagine worst-case scenarios. As director of NEIDL, which he affectionately pronounces like “needle,” Corely coordinates teams who establish and carry out layers of safety protocols. They have a plan for power outages, spills, cyber attacks—basically any risk that most outsiders would deem unthinkable—for their tiered biosafety labs.

In their quest to create Earth-protecting facilities, NASA designers have visited NEIDL to study both their processes and the physical systems that keep the lab clean and secure. While current NASA cleanrooms rely on positive pressure, pathogen containment requires the opposite: rooms with negative pressure that keep air circulating inside the room.

Even though NASA’s original Lunar Receiving Lab combined these systems, technology and biosafety protocols have come a long way since the 1960s. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) didn’t codify its levels of biosafety requirements until 1984, though American agencies began discussing such practices in 1955.

At level one, researchers might be handling a substance like E. coli, a common type of bacteria found in a variety of places, from contaminated food to the human gut. Scientists in these labs use basic personal protective equipment and implement standard cleanliness practices, such as daily decontamination of all equipment and thorough handwashing, to make sure harmful microbes stay where they’re supposed to be. Besides a few biohazard signs and specialized ventilation systems that keep laboratory air inside the lab, these spaces would look familiar to any biology student.

Level two labs deal with slightly more hazardous agents, such as Staphylococcus aureus, an opportunistic pathogen that is also a common part of the body’s microbiome. Security and decontamination practices are more rigorous at this level, but they’re far from extreme.

“At biosafety level three, you’re wearing full Tyvek suits,” says Corely. “You’re wearing a respirator.” Researchers enter the space through vacuum-sealed double doors. Inside, the lab otherwise resembles that of a college biology course—with those hooded lab stations with glass protectors and overhead ventilation. But “at level three, you have to be able to clean and decontaminate everything,” he says. SARS-CoV-2 is kept at level three.

The highest, biosafety level four, is reserved for deadlier pestilences, such as the Ebola virus. Here, scientists wear what Corely calls a fully encapsulated suit, hooked up to hoses that pump air from outside the room. Scientists and the hazardous microbes are completely separated by layers of gloves, goggles, and respirators. They become nesting dolls of safety precautions.

Future extraterrestrial sample curation centers will do the same as a level-four lab. Scientists studying Martian rocks will enter labs wearing a full kit of protective gear. They’ll walk through vacuum-sealed doors into work-spaces with strict designs specialized to keep microbes inside.

Plans to complete such facilities are already underway, though as with other space-exploration endeavors, they will take years to come to fruition, and design adjustments may yet be made.

The Mars Quarantine Facility, which will first host dust and rocks from the red planet in Houston, Texas, may ultimately house astronauts returning from Mars until the agency deems it safe for them to reenter society. Areas will be compartmentalized and HEPA-filtered. ESA, which is working with NASA on sharing and curating future Martian samples, is developing their own similar facility in Vienna, Austria. NASA’s future facilities may even be mobile and modular, mimicking their old Lunar Receiving Lab but with lightweight and streamlined designs.

None of these preparations should be a reason to worry. Agencies are doing this work out of an abundance of caution, not of fear that space germs could take over the planet.

“Andromeda Strain is a good thriller,” says Hubbard. “But there’s very little scientific basis for any of it. The odds of anything from that movie playing out are extremely small.”